THE ICON:TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 10 - East of the Iron Curtain

Оригинал взят у mmekourdukova в THE ICON:TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 10 - East of the Iron Curtain

This chapter will examine a unique situation in the transmission of icon painting. It is a known fact that Russian icon painting, on both sides of the iron curtain, found itself in a difficult situation after 1917. More exactly, there were two situations, neither of them normal.

But first of all, let us remind ourselves of the situation of Russian devotional art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, up to the 1917 Revolution. We knowingly use the term «devotional art» because it would be incorrect, in respect of this period, to speak of icon painting in isolation.

We need to remind ourselves that, in the very last years of the nineteenth and the very first years of the twentieth century, the world of Russian medieval art, and the grand style of Russian medieval iconography simply did not exist, either in the Church or outside. All these masterpieces were hidden from the view, of both the faithful and others, under several layers of overpainting. At that time, what Leonid Uspenski was later to call the «Byzantine style» represented something totally different.

What did exist was:

The above description gives us a snapshot of the state of devotional art and of the art of the Church, and more precisely, of Russian Christian art prior to the discovery of the phenomenon of medieval Russian art.

Three points should be noted at this stage:

First, that it is impossible to limit this vision only to works of devotional art, i.e. works intended for devotional use. In terms of style, and also of the circle of painters or commissioners (consumers), devotional art blends imperceptibly into Church art (works exhibited in churches for educational reasons) and into Christian art in the broad sense of the term (painting of any subject but remaining Christian in its spirit). In all these works the same spirit is manifest, the spirit of good, of moral purity, of peace and truth, sign of the action of the Spirit in the world, and of the leaven that should ideally raise the whole dough.

Second, that it was precisely the role of this leaven which penetrates everywhere that was played by the Academic style. This style provided the common language for devotional painting, for Church painting and for all works of Russian Christian art, while the Byzantine style, even in its religious function, was limited to the sphere of private devotion, and in its worst manifestations, departed even from the sphere of Orthodox veneration of icons, producing rather objects of idolatry.

Third, that the Byzantine style was perceived as inferior to the Academic style, in artistic circles, in church circles, and in society in general. A talented artist, even if he started his career in a «Byzantine» icon workshop, aspired to study systematically at the Academy of Fine Arts. Which did not mean at all that he turned his back to the Church. On the contrary, it was only by undertaking this training that he moved out of the limits of the private consumer market to enter the larger market of Church commissions. As an example we can cite Ilya Repin, who began his career in Ukrainian fresco icon painting teams in the 1870s, and the early twentieth century artist Pavel Korin, trained initially at Palekh. We know of no movements in the reverse direction. It would never have entered the head of an Academically trained artist to step down to the «Byzantine» style, artistically limited, incomparably less in demand from the Church and by the people, associated more with artisanal art, or with the antiquarian and restoration markets and in this context very often with counterfeiting.

But at the beginning of the twentieth century, precious treasures of medieval art were uncovered under multiple overpaintings. A whole world, the forgotten culture of ancient Russia, was rediscovered - to the great delight of the whole of the Christian world, Russian and non-Russian. Not only were lovers of Russian ecclesiastical antiquities impressed, but also entirely lay artists, critics and connoisseurs of the fine arts. The cries of joy of Henri Matisse, who visited Russia in 1910 and became an admirer of the genial artists of the Middle Ages, were echoed across Europe.

But what changed in Russian ecclesiastical art following this discovery? What happened in the few years between the first sensational exhibitions of icons cleaned by the restorer, and the breaking apart of Russian culture in 1917?

However paradoxical it may appear, the answer is: nothing. Nothing had time to change, neither in devotional art, nor in the art of the Church, nor even in Christian art in Russia. The iconographers who for years had painted in the «Byzantine» style felt no need to change in any way their way of painting. Either they were already working «in the old way» (as they understood it), or else their education and their cultural horizons deprived them of the opportunity to open up to the recent discoveries.

On the other hand, Academic artists, educated people, much appreciated the ancient icons. We know the position, typical of his deep piety, of V. Vasnetsov. Then at the height of his glory as a national iconographer, in his letters and verbal comments he considered his works much inferior to the newly discovered art of medieval Russia. Indefatigable in explaining the qualities of this painting to a public brought up in Academic art, he bitterly regretted learning so late of this treasure. But why did neither Vasnetsov, nor Repin, nor Nesterov, nor other well-known artists, who received regular commissions from the Church, start themselves to paint in the Byzantine style?

Precisely because what was opening up before their eyes was a great historical style - or more precisely a whole group of such styles (the Novgorod school of the fourteenth century and that of sixteenth century Moscow being different styles), and not just a series of tricks of the trade which can be imitated by any half-way competent artist. Precisely because, brought up in the true Russian cultural tradition, it was as clear as daylight to them - though not clear even today to the «Theology of the Icon» schools - that medieval artists saw the world in the same way as they painted it, and that imitating them means seeing the world through their eyes, entering deeply into the style, understanding its realism. The immensity of this task was all too clear for them, and this is why they were in no hurry to organize a coup d'état in sacred art. They well understood that the masters of this style were not to be found amongst the Old Believers, nor at Palekh or Mstyora, or - even less - in the workshops of the monasteries or villages working for the open market. It would have been impossible to learn a great historical style from the representatives of a impoverished, fossilized style that had lost its former grandeur, which visibly the Church had no use for when it came to serious commissions, and who themselves saw themselves as artisans, marginal painters or, in the best of cases, as qualified painters in a very limited field, and not as true artists.

Only the true representatives of the «grand Byzantine style» could serve as masters. And as they were all long dead, one would have to learn from their works. A huge labour commenced of collecting, cleaning, classifying, exploring, copying and reconstructing the precious creative heritage of ancient Russia. It was not simply a matter of copying, but of rebuilding a style, purifying it from all the gathered dross of the centuries, everything that rendered it vulgar, false or brutal. And on top of this came the task of educating both the spectator and those commissioning new religious art, unfortunately inclined to spread the bad taste and brutality of contemporary variants of the school onto the ancient chefs-d'oeuvre, quite simply because neither one nor the other looked anything like the Academic painting to which they were accustomed.

A Herculean labor, calling for the coordinated efforts of specialists in several fields for years and decades, not to mention the financial investment, awaited those who had appreciated the recently rediscovered ancient style of painting. It is precisely because they understood this style that they were in no hurry to disguise themselves as «true iconographers». Similarly they avoided any over-hasty attempts to plant the Byzantine style in the Church. Practically the only experiment undertaken by a Church artist (we are not talking, for the time being, of artists outside the Church, like N. Roerich) was the decoration of the Church of the Protection of the Monastery of Martha and Mary in Moscow, begun in 1915 by the young artist P. Korin. His work was accepted, but no more. No overwhelming success in society, no special school or movement for the rebirth of a «grand Byzantine style», nor even a new commission from the Church. The church milieu remained prudent towards stylistic experimentation, and not without reason. We allow ourselves to express this prudent, even suspicious attitude, in the form of a question: you, well-educated artist, have spent years learning to depict man and other objects in the created world in the Academic style that has spread everywhere today. If all of a sudden, you run towards another style for a Church commission, does not this means that the world of Orthodox spirituality is unreal for you, and that for you it is a game, a masquerade, artificial and exterior to you? And the spectator, looking at your icons, will he not also think that Christ and His kingdom are no more than a fable, a fantasy, and not true life?

This question was probably not expressed out loud, but every artist who today uses the Byzantine style for a Church commission also owes an answer to this question to his own artistic conscience. To which there are a variety of replies:

Do we need to explain that it is only in the third case, that is when the Academic artist climbs up to the Byzantine style, not down towards it, does not treat it as a toy, that his work will be beneficial both for the Church (as an act of true exploration of the divine) and for himself (serving his own creative and spiritual growth)? In the second case, with the professional imitation of quality, the artist’s work will indeed fulfill its function in the church, but the author himself will be limited in his creative freedom. He will gain little from working in a style that is exterior to him, and that without a commission he would never come near, for the sake of his soul.

In the first case, on the other hand, the creative interest may even be very great, but that will be an interest purely for oneself, and not for the Church: «And if I were to do something like that, something very old, to create a sensation?» It is in this really blasphemous way that Roerich approached the «Byzantine» style. Artistically his work is expressive and remarkable, but from the spiritual viewpoint it is not just unsuccessful, but positively dangerous, both for himself and the spectator.

It is for this reason that the Church was in no hurry to promote the renaissance of the Byzantine style, but preferred to allow this process to take its natural course in the sphere of the fine arts, according to the laws and logic of this discipline, as it has always done.

During this period, in the final years of the nineteenth and the first years of the twentieth centuries, we observe a second unique phenomenon, the renaissance of the Byzantine style in non-religious art, totally apart from the Church and indeed the Christian faith. Roerich's project at Talashkino was precisely such non-Christian art, masquerading as religious art. The outcome was a scandal, when the Church gave its official opinion, and then only because it had been asked to. The person commissioning the work, totally ignorant of and insensitive to the essentials of Christian sacred imagery, had been so naive as to entrust the decoration of her church to an artist living outside the Church and then invite the Church, via its local hierarchy, to consecrate it. How many other such «Byzantine» exercises did not receive such an opinion because no one asked for it, because the authors were painting for themselves and their own circles, without any pretence to any relationship whatsoever with the Church?! And for how many stiff-necked de facto pagans was not Christianity, and more particularly Russian Orthodoxy, one of those myths of humanity whole sole value was to provide a reservoir of images for building their own artistic egos?

The precious findings of medieval artists, shining revelations of the spirit of love and wisdom, now served the crude naivety of Nathalia Gontcharova, the sad, carnal fantasies of Marc Chagall, the decorative exercises with their theatrical poses of Stelletsky, Malevitch’s malefic red and black constructions..... All these estheticizing apostates were totally uninterested in Christ and the true mystery of Christian art, the image of deified man. Instead they rushed, like a pack of dogs, to tear apart the precious stole woven over the centuries by the culture of the Russian church. Some seized hold of the color schemes based on local tones (each object having a single, basic color), others the expressiveness of the body shapes, others certain physical types, the plastic forms, gilded backgrounds, ornaments, inscriptions.... In all this no distinction was made between the sublime and the primitive. Rather it was precisely primitive «Byzantinism» that was in most demand. It was also easier to imitate and weighed less heavy on the conscience.

All this formed part of an amalgam including stamped tin icons, little popular images and other attributes of «sacred Russia»: peasant embroidery, Tula biscuits, carved toys, matriochskas, balalaïkas and birchwood footwear. This bacchanalia of coarse, superficial imitations of the «popular style» - please note this definition - was highly applauded in the west. This enigmatic country of Russia dazzled westerners with its exotic nature as much as Tibet or Peru. Russian Orthodoxy became a much appreciated component of this exotic bundle of merchandise. And even today we are still unable to evaluate the masters of our silver age from the viewpoint of Christian culture: who among them took a genuinely living and responsible attitude towards the heritage received from ancient Russia, and who simply exploited it, either with facile and irresponsible naivety or, worse, with the open cynicism of a Ham?

It will therefore surprise no one that in the particular cultural and spiritual atmosphere which reigned in Russia at the turn of the century, the Church took a severe and not overly trusting or favorable attitude towards the handful of attempts to revive the «Byzantine style» in sacred art.

Leaving aside the stylistic orgies of Russian art nouveau, there were indeed serious attempts in this direction. Among them we should mention in particular the Committee for the Promotion of Russian Icon Painting. Founded at the start of the twentieth century, this organization brought together historians, archaeologists, restorers and artists. Whilst existing outside the ecclesiastic structures, Its activities doubtless took place in the spirit and received the blessing of the Church. As early as 1902 the committee set up apprenticeship workshops in the four traditional icon-painting villages Palekh, Mstyora, Kholuy and Borisovka, aimed at preserving and promoting the painting of icons in the ancient tradition. Without this centralized support, the old icon-painting craft, by becoming increasingly commercial and losing its most talented young painters to the «grand art», would have been condemned to decay.

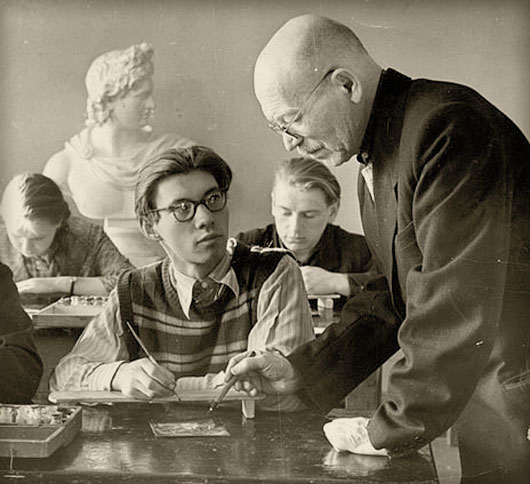

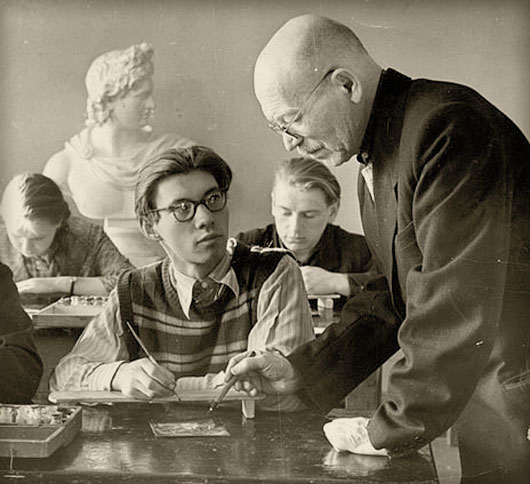

The persons placed in charge of these new apprenticeship workshops were artists trained in the Academic mould. They taught drawing after nature - starting with the simplest shapes, vases and plaster ornaments and moving up to ancient statues and living models. Local masters were invited to teach traditional icon painting techniques. The huge advantage of these schools was to free pupils from the medieval system of paying for their studies by obligatory housework, debasing treatment and the sale of their iconographic work, from an early stage, for the master's financial gain. Also, the Committee's schools did away with the bad commercial tradition of dividing pupils in the very first weeks between «litschniki» and «dolitschniki» («face-painters» and «pre-face-painters»), which had brought about a situation in which face-painters had only a very vague idea of how to paint clothing and landscapes, whilst the painters specializing in clothing and landscapes never saw their finished icons for years on end, all the carnations being painted by other artists, sometimes even in another workshop. In the Committee’s schools, every pupil received training in both specialties and also in the related special tasks of preparing the icon board with the levkas or ground, gilding and stamping.

Needless to say the young people rushed to these schools, at times even leaving existing apprenticeships in other workshops. The latter found themselves emptied of their hewers of wood and fetchers of water, their free child-minders, not to mention the unpaid work of the older apprentices who already helped paint the icons. The discontent of the old workshop masters was expressed in rude comments on the quality of the apprenticeship in the new workshops and, as at Palekh, in the threat to boycott the graduates of these new schools. The first set of graduates from the Palekh school, finding themselves now in danger of being without work in their own village, demanded that their teachers teach them also oil painting, which was the only way for them to find work outside the village. The administration gave way to these supplications and included a little course in oil painting in the final year’s program - but the Committee's inspection commission was firmly opposed, the purpose of these schools being not to find jobs for the young people, but to raise the artistic levels of local icon-painting. The result was that, their studies ended, only a very small percentage of the school’s graduates remained at Palekh, that is the sons of the major workshop owners and less gifted artists who were ready to work for a pittance. All the rest abandoned their native village, almost all of them being obliged to learn Academic painting or find work as restorers. Every year, all the new graduates followed the same pattern. Neither the goodwill of the young iconographers nor the financial investment of the Committee were enough to overcome the resistance of the market and the established ordering and selling system.

Paradoxically, the greatest threat to traditional iconography came, not from the 1917 revolution, but the First World War. Orders dried up, the Committee’s workshops closed and, in particular, a large number of artists, classified as peasants (unlike graduates of the Academy who were granted nobility status), were drafted as soldiers and ended up being killed or mutilated.

In 1918, a small number of iconographers returning home from the trenches were forced to plough the fields to survive, but the more entrepreneurial among them were keen not to forsake their art and looked for new applications in the new environment. Their connections with the connoisseurs of the fine arts in the main Russian cities helped them greatly. The new authorities were encouraging popular art and, paradoxically, the artists who were previously subject to the cruel conditions of the market found themselves in a more favorable situation then before the war.

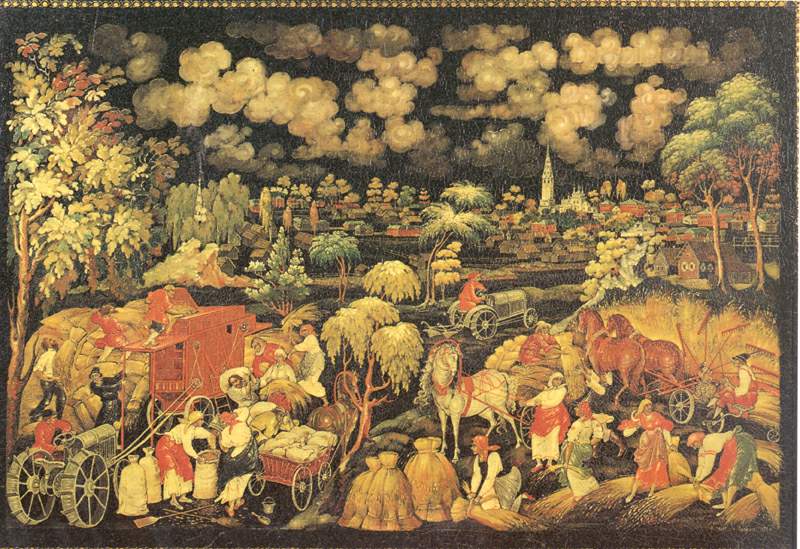

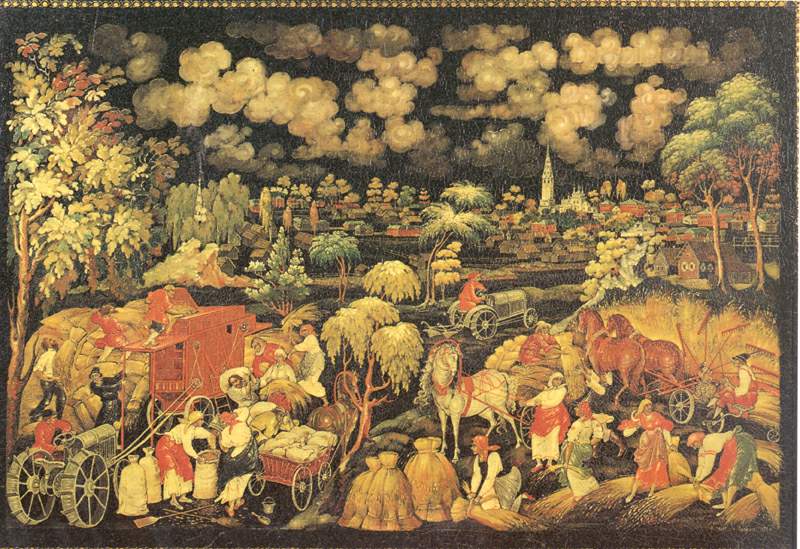

Let us take the village of Palekh as the most typical example. From the beginning of the 1920s, the first experiments of the artists from this village to illustrate the subjects of popular Russian songs and fairy tales, and scenes from country life were highly appreciated by the Moscow Craft Museum, and in this way the «Palekh Confraternity of Ancient Painting» was founded by seven young artists, led by Ivan Golikov. Of course it was only the technique that was ancient. The subjects had changed: village life, folklore, and even classical literature marked the entry of high culture into the lives of peasant-artists, previously almost totally illiterate. The favorite authors were Pushkin and Gorky. The latter, surnamed «the storm petrel of the revolution» found himself in favor with the reconverted iconographers, and for good reason: as a small boy he had begun an apprenticeship in this profession, in a workshop in the style of Palekh. Arriving at the summit of literary glory and of well-being in the Soviet system, he actively aided the Palekh artists who responded with love and recognition.

In 1925 the Confraternity members' works received the Gold Medal of the Paris World Exhibition. The confraternity was already growing, dozens of artists had joined their number; the former peasant-artists’ social star was in the ascendant, as was their level of artistic and general education. In 1931 a professional school was founded for 50 pupils, which still exists as a higher professional training institute. The Palekh artists received major restoration commissions and they were given access to fields of creativity, like illustration and monumental painting, hitherto inaccessible to them.

The same phenomena took place, pretty much simultaneously, in the other historic centres of traditional iconography - at Mstyora and Kholuy. Many artists from these villages became teachers in the professional schools, received state titles, and were decorated. Included in their number were many artists who had trained in iconography at the start of their careers under the old régime. For example Ivan Golikov or Nicolay Zinoviev, both «artists of the people», the highest State grade during the Soviet period.

But let us stop here and foresee the question that the rigorists will ask us: can we treat the iconographic tradition of Palekh, Mstyora and Kholuy as uninterrupted? During half a century, what came off their easels was not icons but scene of kholkoze life, elections of deputies to Soviets, komsomol worksites, the glorious victories of the Red Army.

We will leave it to the rigorists themselves to answer this question. If indeed the traditional «Byzantine» style is per se pneumatophore, as the theologians of the «Paris school» would have us believe, then in perfectly guarding the tradition of this style, the artists of Palekh and Mstyora perfectly kept the spiritual tradition. And a contrario, if Orthodox spirituality cannot be reduced to the «Byzantine» style, one can indeed hesitate in saying that these local centres conserved uninterruptedly the iconographic tradition. But in that case, cannot one equally well call into question the «Byzantine» exercises of those who trace their descent as true iconographers from Leonid Uspenski? What remains then of their «theology of the icon»?

Moreover we should bear in mind that iconography, in the true sense of the word, was never totally suppressed at Palekh and in the other centres. The broad market was indeed brought to an end by the atheist authorities, but individual commissions still found their way to the workshops, coming from the senior hierarchy of the Church, from those concerned with the country’s external policy (a newly painted Russian icon was both a prestigious present and a «witness» to the freedom of the Church in the USSR) and also from the very small circle of very high level scientists and artists who could still proclaim their religious faith without danger. The atheist authorities compounded with this innocent fronde of world-renowned writers, artists and musicians, holding them up as example of religious freedom in the USSR. In this way iconography, albeit as a small stream in a wide river, continued to exist in the ancient centres and the future generations were trained to cover this area too in their future activities. For example the monography ‘The Art of Palekh’ by N. Zinoviev[1], inveterate artist, restorer and teacher at the professional school, first published in the 1960s and reedited later, reproduces the models pupils at the school were required to copy. The overwhelming majority of these drawing and painting models are nothing more or less than fragments of icons. And not just neutral subjects, like rocks, palaces, draperies or plants, but also holy subjects in the true sense of the term. Pupils copied the drawing of the Old Testament Trinity, the figures of John the Baptist, the angel of the desert, the head of Christ or of St Paul the apostle, and all of this not only legally, but as part of the program of a state school confirmed by the Ministry of Culture and on four-year bursaries from the same atheist state. Of course the pupils were enrolled in the komsomols, of course they were subjected to the mandatory antireligious propaganda, but this should not be taken to mean that they automatically became atheists who learned the ancient painting technique with a cold curiosity. More that that, one can state that the school's very high standards, the creative ascesis in which the komsomol members were trained, forced them to at least take seriously the spiritual content of the images they copied.

The silent preaching of the art of the icon «sounded» not just for the hundreds of pupils of the special schools. It sounded also for all those interested in the history of their country, who visited museums and churches converted into museums. Old icons, manuscripts and frescos were accessible to Soviet spectators. The same atheist authorities who closed churches, arrested priests and sent them into exile, or deployed their anti-religious propaganda, paradoxically undertook an enormous task of research, restoration and conservation of the ancient icons. Already in spring 1918, the Ministry of Education organized a special college, the heads of which became the icon expert I.E. Grabar and .... Mme Trotsky, under whose influential wing the college received complete access to all state funds. The most well known restorers and connoisseurs were invited, V.T. Georgievsky, the Tyulin brothers, the Chirikov brothers, P.I. Yukin and a whole series of others. With the blessing of the Patriarch, in the same year the college sent expeditions to Vladimir, Murom, Serguei Posad, the monasteries of Kirilo-Belozersky and Ferapontov, and an enormous labour was begun of research, registration, photography and cleaning of these monuments of ancient art. The researchers and restorers were living cheek by jowl with the horrors of the civil war and terror, with priests and monks being arrested and shot in the churches and monasteries where they were working, but the contact with the precious pearls of ancient art buoyed up the spirits of the exhibition members. It is precisely in the 1920s that were found and cleaned the main works of medieval art, many of which were previously unknown and undocumented, and the existence of which was even unsuspected, hidden under later layers of levkas or brick and plaster. I.E. Grabar exclaimed that he would now have to totally rewrite his History of Russian Art! V.T. Georgievsky, in a letter to the well-known Byzanticist N.P. Kondakov, summed up the situation: "The glory of Rublev, that previously mythical artist, is now a historical fact«.[2]

In other words, from very first days of the Communist era, icons were protected. Not of course as sacred objects, but as objects of art and national treasures. Even more, they were conserved, restored, studied, exhibited and even propagated. Patriotism and a love of national history were encouraged in Soviet Russia and each of its citizens learned whilst still at school that medieval architects and artists, even though deceived by the priests, affirmed, despite the opium of religion, humanist values, the beauty and dignity of the harmonious human personality, motherhood, the power of the Russian state. It is in this way that icons were presented and explained by museum guides, interpreted on the television, in the forewords to albums of reproductions, and even in schoolbooks. Nor was it a lie - all these values are truly present in icons. Only it was not the entire truth. In revenge, the icon itself told the full truth. The official propaganda repeated incessantly that religion is the opium of the people, but the visitors to the exhibitions saw the Kingdom rather than the opium. The image was stronger than its explanation. Which is not surprising: the image is always stronger than its explanation, to the extent that an image which does not represent the Kingdom can ruin any preaching of it! In fact, if they had really wanted to achieve their ends, the propagandists of State atheism would have been better advised to destroy all the chefs-d'oeuvre of ancient painting, and carefully retain all the miserable village craft-shop icons, explaining to the people: here is the art of people drugged by religion. Fortunately this never crossed their minds: they did not know the true and deep theology of the icon - the science which deals with the appearance and action of the artistic image in the Church. To be honest, today still, this science exists more at the level of experience, and the title «Theology of the Icon» is given to texts which handle totally different material. It would be more correct to say that the anti-religious propagandists lacked experience of the Church, and of the direct spiritual action of the artistic image. This is why they allowed the «silent preaching» of the icon. More than that, they encouraged it. And more still, they banned any anti-preaching in the form of bad images. In fact, the twentieth century Communists finally succeeded in applying the decision of the Grand Council of Moscow of 1666-67, which had sought to limit this anti-preaching by banning the fabrication of bad icons. An enormous quantity of such icons were destroyed under the Soviet power, and even greater quantities were left to themselves and perished by natural decomposition, and their production was stopped. Article 162 of the Penal Code of the USSR threatened with prison anyone who brought discredit on God and His Kingdom by manufacturing bad icons, that is, if we may be excused from saying it, by manufacturing them cheaply and routinely for lucrative purposes. This article of the Penal Code did not apply to the professional artists, with state diplomas, who worked on commissions from the Church or the State, restoring, copying and reconstructing icons. In other words, those artists whose witness to the Kingdom was really true and elevated, not only were not persecuted, but even at times paid out of the state coffers. Cheap and unworthy daubing, on the other hand, was finally strictly forbidden.

Special mention needs to be made of private collectors of ancient icons, consisting both of restorers, artists and persons of other professions. Some of them had already begun collecting before the Revolution, for example art connoisseur N.P. Likhachov (1862-1936), artist P.D. Korin (1892-1967), Old Believer priest Fr Isaac Nosov (1847-1940) and Tretyakov Gallery curator I.S. Octroukhov (1858-1929). Others began their collections during the Soviet period, like orchestra conductor N.S. Golovanov, architect A.V. Shusev, ballerina E.V.Geltser, artists N.V. Kusmin and T.A. Mavrina, I.S. Glazunov, writer V.A. Soloukhin, and tens of others. Their collections, though known only to very narrow circles of friends, were indeed part of the cultural milieu of Soviet Russia, this invisible part of the iceberg which is always bigger than the visible part. Without any doubt, the knowledge about and interest in icons and the artistic taste in the field of icons disseminated in this milieu profoundly influenced the country's cultural life. And this knowledge, which was all the more real for being unofficial, provided a breath of fresh air to the official state research and conservation structures. The State had separated the Church from itself, but a love of ancient icons brought together connoisseurs from the church environment, private collectors of every level of religiosity and those in charge of the State collections.

Nor is there any reason to believe that the witness to the truth of Soviet restorers and artists undertaking commissions for the Church was mechanical or unreflected. According the laws of artistic creativity, in particular in the case of highly professional work, a mechanical witness is simply impossible. This was even truer in the difficult, pretty sad and false conditions of official Soviet culture: anything that touched the eternal, the absolute, was doubly precious. One can responsibly say that among the thousands of persons whose profession brought them into contact with icons during the Soviet period, whether as restorers, artists, researchers or museum curators, there was not a single convinced atheist. At the least, these people maintained a profound respect for the «medieval mentality» and at vaguely guessed that it was based on the truth. Certain of them went a step further and arrived at a conscious faith, some dared to cross the threshold of the Church, but in general this milieu was the least accessible to the ideological pressure and control of the State.

A restorer who was a believer, even with his party membership card in his pocket, could easily find a formal justification for attending Church services, for visiting a monastery, for discussing with priests. A believing historian or art theoretician had easy access to the special library funds containing spiritual literature (the author of this article herself, whilst still a student, did the same), whilst it was very difficult, even for a priest, to obtain a Gospel or a prayer book. A guide who was a believer could, legally, and for a salary, preach, of course within certain limits, to groups of Soviet schoolchildren, who were unable to attend church services at a time when public teaching of religion was a criminal act. For this reason it comes as no surprise that the renaissance of faith in Russia owes much to this «fifth column» which has given members of the clergy, monks and nuns, not to mention a whole army of active lay persons who, once the Church received the green light from the state to organize social services, developed them - in the press, in culture, teaching, charitable works - in unheard-of dimensions.

Let us return to these three phenomena we described earlier:

It is well known that attempts to safeguard a spiritual tradition by taking a purely conservative attitude are vowed sooner or later to failure. Without creative development, without forward movement, a tradition loses breath and dies. The Soviet period was one of significant progress in the technical tradition and knowledge of icon painting. During it the half-peasants, half-craftsmen of Palekh and Mstyora were converted into true artists, achieving a social status and a level of general education accessible at the beginning of the century to only a small number of them, and then mainly to those who abandoned the ancient way of painting for the Academic manner. The favors of the State and the de-commercialization of their art enabled them to reach a much higher professional level. Restoration and reconstructive copying also reached a level inconceivable at the start of the century. Not only with new technologies, apparatus and chemicals but also specialist skills: in Soviet Russia restorers of tempera painting began - after a very strict entry competition - a higher training lasting at least 5 years. The number and quality of ancient icons that were freed of their overpaintings during the Soviet period far exceed all that was done in this direction before the Revolution. For proof of this one needs only to leaf through the catalogs of collections of Russian icons, giving for every icon the date of its cleaning. And the role played in the spiritual rebirth of Russia by the people attached professionally to icons is eloquent testimony to their spiritual development.

But our essay would not be complete without mentioning one of the most remarkable personalities in this field in terms of her influence on contemporary Russian iconography, a person also with an irreproachable church record. I am taking of the life and activity of Mother Juliania (Maria Nikolayevna Sokolova, 1899 - 1981), a unique personality in whom we can recognize an artist, a connoisseur and a righteous person, at a time when life was hard in each of these categories.

As the daughter of a priest, Maria Nikolayevna was close to the world of icons since her childhood. Her father was artistically gifted and combined his liturgical activities with iconography, copying in oil the pictures of Nesterov and Vasnetsov that were particularly popular at the time. Maria received her first lessons in drawing and painting - naturally in the Academic manner - from her father. In this way she learned from experience that, in sacred art, it is the spirit and not the style which is the most important, and that the style is good in so far as it expresses naturally the spiritual, whether the style and spirit of a historical epoch, or that of a particular artist. Orphaned early in life, Maria Nikolayevna had the good fortune, in the first years after the Revolution, to meet in the famished and ruined Moscow of her day Father Alexei Metchov, who became her protector and spiritual father, and who blessed her for the ascesis of icon painting. After Father Alexei’s death the parish passed to his son, Fr Serguei Metchov, recently canonized as a priest-martyr. A great lover and connoisseur of ancient icons, Father Serguei found, even in these years, a possibility to undertake restoration work in his church, and to invite qualified Old Believers to restore icons. It was he who introduced Maria Nikolayevna to Vladmir Komarovski (1883-1937), a well-known specialist in monumental church painting and to Vassili Kirikov, an iconographer and restorer, with whom she commenced regular studies from the mid-twenties onwards. At that time she had already graduated as a graphic artist and worked in a publishing company. As well as a salary, this gave her a legal existence in the USSR, but her real work was icon painting. After the Academic school of drawing and painting, with lessons and advice from connoisseurs of ancient icons, she began a serious apprenticeship by studying directly the past masters of the art, producing an enormous number of drawings and color studies from ancient icons, frescos and prorisi (pattern books) of every school and period. Nor did she rush to grab hold of what is superficial and exotic in the artistic language of the icon - much appreciated by charlatans and the poorly instructed. The realism of medieval painting opened up to her as a true realism, and not a retreat from Academicism. By freeing herself gradually from every trace of superficial decorativeness, she lived the style of the ancient Russian icon, or more precisely that of the Moscow school of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, her fine and complex research uninfluenced by the tastes of icon-buyers and markets that no longer existed. There were just two «controlling bodies»: a profound understanding, rooted in the Church, of the meaning of the icon, and a sort of uncompromising honesty of a professional artist who does not want to reduce his art to a cheap primitivism, but who feels himself called to infinite perfection.

Hence, starting from the work of a single artist, the ancient iconographic style was reborn, in Russia itself. Not from the lifeless copying of a certain number of masterpieces, nor as an esoteric amusement including grinding little stones and learning by heart little incantatory prayers with which to accompany one’s painting, nor by irresponsible creative experiments, but in the only form worthy of a Christian artist, that of freely following a tradition appropriated by careful study, in the form of a grand style that can respond fully to the spiritual and aesthetic demands of the spectator and the artist.

Through the providence of God, this work, this prowess of several years was ratified by the Church, in the most prestigious fashion. Maria Nikolayevna’s first «commission» was the task of restoration and reconstruction in the Lavra of Trinity-Saint Sergius. Let us place this in its historical context: during World War II, the government revised its relations with the Orthodox Church. The patriarchate was reestablished, a large portion of the imprisoned priests and bishops were amnestied, and certain churches and monasteries, including the Lavra of Trinity-Saint Sergius, were reopened for public worship. In 1946 Maria Nikolayevna took charge of this work, surrounded by a group of specialists from the semi-clandestine layer of intelligentsia who were either believers or very close to the faith. This marked the start of 35 years of incessant and fruitful service in the Church as a restorer, artist, consultant and teacher. Maria Nikolayevna had many pupils, first of all her workshop helpers, but also artists who took private lessons, and later regular students on a permanent basis. From 1958 to her death, she directed the icon-painting circle at the theological academy of the Lavra of Trinity-Saint Sergius, drawing and painting hundreds of sketches and models for copying. She wrote books on the technique of icon painting, works on teaching methodology, and essays explaining icons to a wide public. In 1990 her circle firmed the basis for the iconography school at the Moscow Theological Academy, today led by Higoumen Luka Golovkov. The majority of today's most eminent Russian iconographers are pupils of Maria Nikolayeva. To name at least the oldest and most eminent among them: Nathalia Aldoschina, Irina Vataguina, Father Nikolay Chernyshev....

A large number of other younger artists have undertaken the same career path in parallel, starting with an Academic training and continuing as autodidacts following the paths of the medieval masters. The best known of them is Archimandrite Zinon Theodore, born in 1954.

We must stop here. Even the most rapid look at contemporary Russian iconography would have demanded several more pages, indeed a whole book. If only mentioning the best known artists, schools and workshops, the most widespread stylistic trends, and the most significant events in the history of icon painting during these recent decades, the work would have represented a mass of information which would have gone well beyond the confines of our exposé. We mention here only that which relates directly to the affirmation of the thesis that the icon-painting tradition continued uninterruptedly and authentically in Russia.

Let us now go back nearly a century and try and understand the origins, the development and the current status of the other line of the tradition of icon painting, the line that is to be found on the western side of the former «iron curtain.»

[1] N. Zinoviev, Iskousstvo Palekha, Leningrad, 1974.

[2] Vestnik RKhD no. 136, Paris, New York, Moscow, 1982, p. 242-244

This chapter will examine a unique situation in the transmission of icon painting. It is a known fact that Russian icon painting, on both sides of the iron curtain, found itself in a difficult situation after 1917. More exactly, there were two situations, neither of them normal.

But first of all, let us remind ourselves of the situation of Russian devotional art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, up to the 1917 Revolution. We knowingly use the term «devotional art» because it would be incorrect, in respect of this period, to speak of icon painting in isolation.

We need to remind ourselves that, in the very last years of the nineteenth and the very first years of the twentieth century, the world of Russian medieval art, and the grand style of Russian medieval iconography simply did not exist, either in the Church or outside. All these masterpieces were hidden from the view, of both the faithful and others, under several layers of overpainting. At that time, what Leonid Uspenski was later to call the «Byzantine style» represented something totally different.

What did exist was:

- icon painting in the «Academic style». This was indisputably the dominant direction, in terms of the number of commissions for churches, the number of artists mastering this style, and the professionalism of the best among them;

- icon painting in the «Byzantine» style, at a high professional level. This was undertaken by isolated masters, the majority of them Old Believers, working almost exclusively for private customers, having long lost the practice of large format painting (iconostases and frescos). Into the same group one can place the iconographers of the artist-villages Palekh and Mstyora;

- icon painting in the «Byzantine» style from monastic workshops. Compared with the previous, more elevated variant, this is dryer, decorative, meticulous, and iconographically even more limited. The monastic workshops spent most of their time producing little images of the most popular icons for sale to pilgrims. (On can add here that certain monastic workshops also produced icons of quite poor quality in the Academic style.);

- serial icon painting in a «primitive Byzantine» by other craft workshops. This production ranged from isolated chefs-d’oeuvres, albeit somewhat barbarous, of popular creativity, like for example Ukrainian icons on glass, or the production of the artist-village Kholuy, to products of extreme vulgarity for the aesthetically and theologically least demanding consumers;

- paintings in the Academic style of subjects taken from the New Testament or the history of the Church or of miracles, commissioned by parishes, monasteries and churches in hospitals and other institutions. In this group we should include the mural and easel paintings which were placed in churches, the easel paintings hung elsewhere, and engravings, which were never hung in churches. But they shared a common iconography (canonical or not totally canonical): the engravings were produced from paintings, and in turn served as models for mural paintings, and vice versa frescos were reproduced in easel paintings;

- paintings in the Academic style on subjects taken from the Old and New Testament and the history of the Church, miracle scenes or images of saints, not painted on commission but as an expression of a Christian painter's creative credo. We mention them here because they were bought, not only by private individuals, but also by church organizations and because, even more often, copies of them were ordered for churches, from the original painter himself or from other artists. We should point out here that if an artist had exhibited such a copy anywhere else, he would have been cried down as a plagiarist, but that in the consciousness of the Church, the same action was seen, not as a theft, shameful to the thief and injurious to the original painter, but as the application of a common right to the entire artistic treasure of the Church.

The above description gives us a snapshot of the state of devotional art and of the art of the Church, and more precisely, of Russian Christian art prior to the discovery of the phenomenon of medieval Russian art.

Three points should be noted at this stage:

First, that it is impossible to limit this vision only to works of devotional art, i.e. works intended for devotional use. In terms of style, and also of the circle of painters or commissioners (consumers), devotional art blends imperceptibly into Church art (works exhibited in churches for educational reasons) and into Christian art in the broad sense of the term (painting of any subject but remaining Christian in its spirit). In all these works the same spirit is manifest, the spirit of good, of moral purity, of peace and truth, sign of the action of the Spirit in the world, and of the leaven that should ideally raise the whole dough.

Second, that it was precisely the role of this leaven which penetrates everywhere that was played by the Academic style. This style provided the common language for devotional painting, for Church painting and for all works of Russian Christian art, while the Byzantine style, even in its religious function, was limited to the sphere of private devotion, and in its worst manifestations, departed even from the sphere of Orthodox veneration of icons, producing rather objects of idolatry.

Third, that the Byzantine style was perceived as inferior to the Academic style, in artistic circles, in church circles, and in society in general. A talented artist, even if he started his career in a «Byzantine» icon workshop, aspired to study systematically at the Academy of Fine Arts. Which did not mean at all that he turned his back to the Church. On the contrary, it was only by undertaking this training that he moved out of the limits of the private consumer market to enter the larger market of Church commissions. As an example we can cite Ilya Repin, who began his career in Ukrainian fresco icon painting teams in the 1870s, and the early twentieth century artist Pavel Korin, trained initially at Palekh. We know of no movements in the reverse direction. It would never have entered the head of an Academically trained artist to step down to the «Byzantine» style, artistically limited, incomparably less in demand from the Church and by the people, associated more with artisanal art, or with the antiquarian and restoration markets and in this context very often with counterfeiting.

But at the beginning of the twentieth century, precious treasures of medieval art were uncovered under multiple overpaintings. A whole world, the forgotten culture of ancient Russia, was rediscovered - to the great delight of the whole of the Christian world, Russian and non-Russian. Not only were lovers of Russian ecclesiastical antiquities impressed, but also entirely lay artists, critics and connoisseurs of the fine arts. The cries of joy of Henri Matisse, who visited Russia in 1910 and became an admirer of the genial artists of the Middle Ages, were echoed across Europe.

But what changed in Russian ecclesiastical art following this discovery? What happened in the few years between the first sensational exhibitions of icons cleaned by the restorer, and the breaking apart of Russian culture in 1917?

However paradoxical it may appear, the answer is: nothing. Nothing had time to change, neither in devotional art, nor in the art of the Church, nor even in Christian art in Russia. The iconographers who for years had painted in the «Byzantine» style felt no need to change in any way their way of painting. Either they were already working «in the old way» (as they understood it), or else their education and their cultural horizons deprived them of the opportunity to open up to the recent discoveries.

On the other hand, Academic artists, educated people, much appreciated the ancient icons. We know the position, typical of his deep piety, of V. Vasnetsov. Then at the height of his glory as a national iconographer, in his letters and verbal comments he considered his works much inferior to the newly discovered art of medieval Russia. Indefatigable in explaining the qualities of this painting to a public brought up in Academic art, he bitterly regretted learning so late of this treasure. But why did neither Vasnetsov, nor Repin, nor Nesterov, nor other well-known artists, who received regular commissions from the Church, start themselves to paint in the Byzantine style?

Precisely because what was opening up before their eyes was a great historical style - or more precisely a whole group of such styles (the Novgorod school of the fourteenth century and that of sixteenth century Moscow being different styles), and not just a series of tricks of the trade which can be imitated by any half-way competent artist. Precisely because, brought up in the true Russian cultural tradition, it was as clear as daylight to them - though not clear even today to the «Theology of the Icon» schools - that medieval artists saw the world in the same way as they painted it, and that imitating them means seeing the world through their eyes, entering deeply into the style, understanding its realism. The immensity of this task was all too clear for them, and this is why they were in no hurry to organize a coup d'état in sacred art. They well understood that the masters of this style were not to be found amongst the Old Believers, nor at Palekh or Mstyora, or - even less - in the workshops of the monasteries or villages working for the open market. It would have been impossible to learn a great historical style from the representatives of a impoverished, fossilized style that had lost its former grandeur, which visibly the Church had no use for when it came to serious commissions, and who themselves saw themselves as artisans, marginal painters or, in the best of cases, as qualified painters in a very limited field, and not as true artists.

Only the true representatives of the «grand Byzantine style» could serve as masters. And as they were all long dead, one would have to learn from their works. A huge labour commenced of collecting, cleaning, classifying, exploring, copying and reconstructing the precious creative heritage of ancient Russia. It was not simply a matter of copying, but of rebuilding a style, purifying it from all the gathered dross of the centuries, everything that rendered it vulgar, false or brutal. And on top of this came the task of educating both the spectator and those commissioning new religious art, unfortunately inclined to spread the bad taste and brutality of contemporary variants of the school onto the ancient chefs-d'oeuvre, quite simply because neither one nor the other looked anything like the Academic painting to which they were accustomed.

A Herculean labor, calling for the coordinated efforts of specialists in several fields for years and decades, not to mention the financial investment, awaited those who had appreciated the recently rediscovered ancient style of painting. It is precisely because they understood this style that they were in no hurry to disguise themselves as «true iconographers». Similarly they avoided any over-hasty attempts to plant the Byzantine style in the Church. Practically the only experiment undertaken by a Church artist (we are not talking, for the time being, of artists outside the Church, like N. Roerich) was the decoration of the Church of the Protection of the Monastery of Martha and Mary in Moscow, begun in 1915 by the young artist P. Korin. His work was accepted, but no more. No overwhelming success in society, no special school or movement for the rebirth of a «grand Byzantine style», nor even a new commission from the Church. The church milieu remained prudent towards stylistic experimentation, and not without reason. We allow ourselves to express this prudent, even suspicious attitude, in the form of a question: you, well-educated artist, have spent years learning to depict man and other objects in the created world in the Academic style that has spread everywhere today. If all of a sudden, you run towards another style for a Church commission, does not this means that the world of Orthodox spirituality is unreal for you, and that for you it is a game, a masquerade, artificial and exterior to you? And the spectator, looking at your icons, will he not also think that Christ and His kingdom are no more than a fable, a fantasy, and not true life?

This question was probably not expressed out loud, but every artist who today uses the Byzantine style for a Church commission also owes an answer to this question to his own artistic conscience. To which there are a variety of replies:

- It’s none of your business, whether this Byzantine style is my real face or a mask. I like this mask, it makes me look good, gives me a positive image.

- I am a professional, and if the person commissioning the painting insists on the Byzantine style, I can imitate it, absolutely professionally, by laying aside my own creative ambitions.

- Maybe I am still unworthy of calling mine the style of the medieval artists, but I aspire to it with all my heart, and realize that all my knowledge is still insufficient: images used for prayer should not only look like real people, but each brush stroke must be beautiful and harmonious. The school in which I was trained no longer satisfies me, and I am constantly using tricks of the trade taken from Byzantine painting, whether working for myself or on commission, in both religious and in non-religious painting.

Do we need to explain that it is only in the third case, that is when the Academic artist climbs up to the Byzantine style, not down towards it, does not treat it as a toy, that his work will be beneficial both for the Church (as an act of true exploration of the divine) and for himself (serving his own creative and spiritual growth)? In the second case, with the professional imitation of quality, the artist’s work will indeed fulfill its function in the church, but the author himself will be limited in his creative freedom. He will gain little from working in a style that is exterior to him, and that without a commission he would never come near, for the sake of his soul.

In the first case, on the other hand, the creative interest may even be very great, but that will be an interest purely for oneself, and not for the Church: «And if I were to do something like that, something very old, to create a sensation?» It is in this really blasphemous way that Roerich approached the «Byzantine» style. Artistically his work is expressive and remarkable, but from the spiritual viewpoint it is not just unsuccessful, but positively dangerous, both for himself and the spectator.

It is for this reason that the Church was in no hurry to promote the renaissance of the Byzantine style, but preferred to allow this process to take its natural course in the sphere of the fine arts, according to the laws and logic of this discipline, as it has always done.

During this period, in the final years of the nineteenth and the first years of the twentieth centuries, we observe a second unique phenomenon, the renaissance of the Byzantine style in non-religious art, totally apart from the Church and indeed the Christian faith. Roerich's project at Talashkino was precisely such non-Christian art, masquerading as religious art. The outcome was a scandal, when the Church gave its official opinion, and then only because it had been asked to. The person commissioning the work, totally ignorant of and insensitive to the essentials of Christian sacred imagery, had been so naive as to entrust the decoration of her church to an artist living outside the Church and then invite the Church, via its local hierarchy, to consecrate it. How many other such «Byzantine» exercises did not receive such an opinion because no one asked for it, because the authors were painting for themselves and their own circles, without any pretence to any relationship whatsoever with the Church?! And for how many stiff-necked de facto pagans was not Christianity, and more particularly Russian Orthodoxy, one of those myths of humanity whole sole value was to provide a reservoir of images for building their own artistic egos?

The precious findings of medieval artists, shining revelations of the spirit of love and wisdom, now served the crude naivety of Nathalia Gontcharova, the sad, carnal fantasies of Marc Chagall, the decorative exercises with their theatrical poses of Stelletsky, Malevitch’s malefic red and black constructions..... All these estheticizing apostates were totally uninterested in Christ and the true mystery of Christian art, the image of deified man. Instead they rushed, like a pack of dogs, to tear apart the precious stole woven over the centuries by the culture of the Russian church. Some seized hold of the color schemes based on local tones (each object having a single, basic color), others the expressiveness of the body shapes, others certain physical types, the plastic forms, gilded backgrounds, ornaments, inscriptions.... In all this no distinction was made between the sublime and the primitive. Rather it was precisely primitive «Byzantinism» that was in most demand. It was also easier to imitate and weighed less heavy on the conscience.

All this formed part of an amalgam including stamped tin icons, little popular images and other attributes of «sacred Russia»: peasant embroidery, Tula biscuits, carved toys, matriochskas, balalaïkas and birchwood footwear. This bacchanalia of coarse, superficial imitations of the «popular style» - please note this definition - was highly applauded in the west. This enigmatic country of Russia dazzled westerners with its exotic nature as much as Tibet or Peru. Russian Orthodoxy became a much appreciated component of this exotic bundle of merchandise. And even today we are still unable to evaluate the masters of our silver age from the viewpoint of Christian culture: who among them took a genuinely living and responsible attitude towards the heritage received from ancient Russia, and who simply exploited it, either with facile and irresponsible naivety or, worse, with the open cynicism of a Ham?

It will therefore surprise no one that in the particular cultural and spiritual atmosphere which reigned in Russia at the turn of the century, the Church took a severe and not overly trusting or favorable attitude towards the handful of attempts to revive the «Byzantine style» in sacred art.

Leaving aside the stylistic orgies of Russian art nouveau, there were indeed serious attempts in this direction. Among them we should mention in particular the Committee for the Promotion of Russian Icon Painting. Founded at the start of the twentieth century, this organization brought together historians, archaeologists, restorers and artists. Whilst existing outside the ecclesiastic structures, Its activities doubtless took place in the spirit and received the blessing of the Church. As early as 1902 the committee set up apprenticeship workshops in the four traditional icon-painting villages Palekh, Mstyora, Kholuy and Borisovka, aimed at preserving and promoting the painting of icons in the ancient tradition. Without this centralized support, the old icon-painting craft, by becoming increasingly commercial and losing its most talented young painters to the «grand art», would have been condemned to decay.

The persons placed in charge of these new apprenticeship workshops were artists trained in the Academic mould. They taught drawing after nature - starting with the simplest shapes, vases and plaster ornaments and moving up to ancient statues and living models. Local masters were invited to teach traditional icon painting techniques. The huge advantage of these schools was to free pupils from the medieval system of paying for their studies by obligatory housework, debasing treatment and the sale of their iconographic work, from an early stage, for the master's financial gain. Also, the Committee's schools did away with the bad commercial tradition of dividing pupils in the very first weeks between «litschniki» and «dolitschniki» («face-painters» and «pre-face-painters»), which had brought about a situation in which face-painters had only a very vague idea of how to paint clothing and landscapes, whilst the painters specializing in clothing and landscapes never saw their finished icons for years on end, all the carnations being painted by other artists, sometimes even in another workshop. In the Committee’s schools, every pupil received training in both specialties and also in the related special tasks of preparing the icon board with the levkas or ground, gilding and stamping.

Needless to say the young people rushed to these schools, at times even leaving existing apprenticeships in other workshops. The latter found themselves emptied of their hewers of wood and fetchers of water, their free child-minders, not to mention the unpaid work of the older apprentices who already helped paint the icons. The discontent of the old workshop masters was expressed in rude comments on the quality of the apprenticeship in the new workshops and, as at Palekh, in the threat to boycott the graduates of these new schools. The first set of graduates from the Palekh school, finding themselves now in danger of being without work in their own village, demanded that their teachers teach them also oil painting, which was the only way for them to find work outside the village. The administration gave way to these supplications and included a little course in oil painting in the final year’s program - but the Committee's inspection commission was firmly opposed, the purpose of these schools being not to find jobs for the young people, but to raise the artistic levels of local icon-painting. The result was that, their studies ended, only a very small percentage of the school’s graduates remained at Palekh, that is the sons of the major workshop owners and less gifted artists who were ready to work for a pittance. All the rest abandoned their native village, almost all of them being obliged to learn Academic painting or find work as restorers. Every year, all the new graduates followed the same pattern. Neither the goodwill of the young iconographers nor the financial investment of the Committee were enough to overcome the resistance of the market and the established ordering and selling system.

Paradoxically, the greatest threat to traditional iconography came, not from the 1917 revolution, but the First World War. Orders dried up, the Committee’s workshops closed and, in particular, a large number of artists, classified as peasants (unlike graduates of the Academy who were granted nobility status), were drafted as soldiers and ended up being killed or mutilated.

In 1918, a small number of iconographers returning home from the trenches were forced to plough the fields to survive, but the more entrepreneurial among them were keen not to forsake their art and looked for new applications in the new environment. Their connections with the connoisseurs of the fine arts in the main Russian cities helped them greatly. The new authorities were encouraging popular art and, paradoxically, the artists who were previously subject to the cruel conditions of the market found themselves in a more favorable situation then before the war.

Let us take the village of Palekh as the most typical example. From the beginning of the 1920s, the first experiments of the artists from this village to illustrate the subjects of popular Russian songs and fairy tales, and scenes from country life were highly appreciated by the Moscow Craft Museum, and in this way the «Palekh Confraternity of Ancient Painting» was founded by seven young artists, led by Ivan Golikov. Of course it was only the technique that was ancient. The subjects had changed: village life, folklore, and even classical literature marked the entry of high culture into the lives of peasant-artists, previously almost totally illiterate. The favorite authors were Pushkin and Gorky. The latter, surnamed «the storm petrel of the revolution» found himself in favor with the reconverted iconographers, and for good reason: as a small boy he had begun an apprenticeship in this profession, in a workshop in the style of Palekh. Arriving at the summit of literary glory and of well-being in the Soviet system, he actively aided the Palekh artists who responded with love and recognition.

In 1925 the Confraternity members' works received the Gold Medal of the Paris World Exhibition. The confraternity was already growing, dozens of artists had joined their number; the former peasant-artists’ social star was in the ascendant, as was their level of artistic and general education. In 1931 a professional school was founded for 50 pupils, which still exists as a higher professional training institute. The Palekh artists received major restoration commissions and they were given access to fields of creativity, like illustration and monumental painting, hitherto inaccessible to them.

The same phenomena took place, pretty much simultaneously, in the other historic centres of traditional iconography - at Mstyora and Kholuy. Many artists from these villages became teachers in the professional schools, received state titles, and were decorated. Included in their number were many artists who had trained in iconography at the start of their careers under the old régime. For example Ivan Golikov or Nicolay Zinoviev, both «artists of the people», the highest State grade during the Soviet period.

But let us stop here and foresee the question that the rigorists will ask us: can we treat the iconographic tradition of Palekh, Mstyora and Kholuy as uninterrupted? During half a century, what came off their easels was not icons but scene of kholkoze life, elections of deputies to Soviets, komsomol worksites, the glorious victories of the Red Army.

We will leave it to the rigorists themselves to answer this question. If indeed the traditional «Byzantine» style is per se pneumatophore, as the theologians of the «Paris school» would have us believe, then in perfectly guarding the tradition of this style, the artists of Palekh and Mstyora perfectly kept the spiritual tradition. And a contrario, if Orthodox spirituality cannot be reduced to the «Byzantine» style, one can indeed hesitate in saying that these local centres conserved uninterruptedly the iconographic tradition. But in that case, cannot one equally well call into question the «Byzantine» exercises of those who trace their descent as true iconographers from Leonid Uspenski? What remains then of their «theology of the icon»?

Moreover we should bear in mind that iconography, in the true sense of the word, was never totally suppressed at Palekh and in the other centres. The broad market was indeed brought to an end by the atheist authorities, but individual commissions still found their way to the workshops, coming from the senior hierarchy of the Church, from those concerned with the country’s external policy (a newly painted Russian icon was both a prestigious present and a «witness» to the freedom of the Church in the USSR) and also from the very small circle of very high level scientists and artists who could still proclaim their religious faith without danger. The atheist authorities compounded with this innocent fronde of world-renowned writers, artists and musicians, holding them up as example of religious freedom in the USSR. In this way iconography, albeit as a small stream in a wide river, continued to exist in the ancient centres and the future generations were trained to cover this area too in their future activities. For example the monography ‘The Art of Palekh’ by N. Zinoviev[1], inveterate artist, restorer and teacher at the professional school, first published in the 1960s and reedited later, reproduces the models pupils at the school were required to copy. The overwhelming majority of these drawing and painting models are nothing more or less than fragments of icons. And not just neutral subjects, like rocks, palaces, draperies or plants, but also holy subjects in the true sense of the term. Pupils copied the drawing of the Old Testament Trinity, the figures of John the Baptist, the angel of the desert, the head of Christ or of St Paul the apostle, and all of this not only legally, but as part of the program of a state school confirmed by the Ministry of Culture and on four-year bursaries from the same atheist state. Of course the pupils were enrolled in the komsomols, of course they were subjected to the mandatory antireligious propaganda, but this should not be taken to mean that they automatically became atheists who learned the ancient painting technique with a cold curiosity. More that that, one can state that the school's very high standards, the creative ascesis in which the komsomol members were trained, forced them to at least take seriously the spiritual content of the images they copied.

The silent preaching of the art of the icon «sounded» not just for the hundreds of pupils of the special schools. It sounded also for all those interested in the history of their country, who visited museums and churches converted into museums. Old icons, manuscripts and frescos were accessible to Soviet spectators. The same atheist authorities who closed churches, arrested priests and sent them into exile, or deployed their anti-religious propaganda, paradoxically undertook an enormous task of research, restoration and conservation of the ancient icons. Already in spring 1918, the Ministry of Education organized a special college, the heads of which became the icon expert I.E. Grabar and .... Mme Trotsky, under whose influential wing the college received complete access to all state funds. The most well known restorers and connoisseurs were invited, V.T. Georgievsky, the Tyulin brothers, the Chirikov brothers, P.I. Yukin and a whole series of others. With the blessing of the Patriarch, in the same year the college sent expeditions to Vladimir, Murom, Serguei Posad, the monasteries of Kirilo-Belozersky and Ferapontov, and an enormous labour was begun of research, registration, photography and cleaning of these monuments of ancient art. The researchers and restorers were living cheek by jowl with the horrors of the civil war and terror, with priests and monks being arrested and shot in the churches and monasteries where they were working, but the contact with the precious pearls of ancient art buoyed up the spirits of the exhibition members. It is precisely in the 1920s that were found and cleaned the main works of medieval art, many of which were previously unknown and undocumented, and the existence of which was even unsuspected, hidden under later layers of levkas or brick and plaster. I.E. Grabar exclaimed that he would now have to totally rewrite his History of Russian Art! V.T. Georgievsky, in a letter to the well-known Byzanticist N.P. Kondakov, summed up the situation: "The glory of Rublev, that previously mythical artist, is now a historical fact«.[2]

In other words, from very first days of the Communist era, icons were protected. Not of course as sacred objects, but as objects of art and national treasures. Even more, they were conserved, restored, studied, exhibited and even propagated. Patriotism and a love of national history were encouraged in Soviet Russia and each of its citizens learned whilst still at school that medieval architects and artists, even though deceived by the priests, affirmed, despite the opium of religion, humanist values, the beauty and dignity of the harmonious human personality, motherhood, the power of the Russian state. It is in this way that icons were presented and explained by museum guides, interpreted on the television, in the forewords to albums of reproductions, and even in schoolbooks. Nor was it a lie - all these values are truly present in icons. Only it was not the entire truth. In revenge, the icon itself told the full truth. The official propaganda repeated incessantly that religion is the opium of the people, but the visitors to the exhibitions saw the Kingdom rather than the opium. The image was stronger than its explanation. Which is not surprising: the image is always stronger than its explanation, to the extent that an image which does not represent the Kingdom can ruin any preaching of it! In fact, if they had really wanted to achieve their ends, the propagandists of State atheism would have been better advised to destroy all the chefs-d'oeuvre of ancient painting, and carefully retain all the miserable village craft-shop icons, explaining to the people: here is the art of people drugged by religion. Fortunately this never crossed their minds: they did not know the true and deep theology of the icon - the science which deals with the appearance and action of the artistic image in the Church. To be honest, today still, this science exists more at the level of experience, and the title «Theology of the Icon» is given to texts which handle totally different material. It would be more correct to say that the anti-religious propagandists lacked experience of the Church, and of the direct spiritual action of the artistic image. This is why they allowed the «silent preaching» of the icon. More than that, they encouraged it. And more still, they banned any anti-preaching in the form of bad images. In fact, the twentieth century Communists finally succeeded in applying the decision of the Grand Council of Moscow of 1666-67, which had sought to limit this anti-preaching by banning the fabrication of bad icons. An enormous quantity of such icons were destroyed under the Soviet power, and even greater quantities were left to themselves and perished by natural decomposition, and their production was stopped. Article 162 of the Penal Code of the USSR threatened with prison anyone who brought discredit on God and His Kingdom by manufacturing bad icons, that is, if we may be excused from saying it, by manufacturing them cheaply and routinely for lucrative purposes. This article of the Penal Code did not apply to the professional artists, with state diplomas, who worked on commissions from the Church or the State, restoring, copying and reconstructing icons. In other words, those artists whose witness to the Kingdom was really true and elevated, not only were not persecuted, but even at times paid out of the state coffers. Cheap and unworthy daubing, on the other hand, was finally strictly forbidden.

Special mention needs to be made of private collectors of ancient icons, consisting both of restorers, artists and persons of other professions. Some of them had already begun collecting before the Revolution, for example art connoisseur N.P. Likhachov (1862-1936), artist P.D. Korin (1892-1967), Old Believer priest Fr Isaac Nosov (1847-1940) and Tretyakov Gallery curator I.S. Octroukhov (1858-1929). Others began their collections during the Soviet period, like orchestra conductor N.S. Golovanov, architect A.V. Shusev, ballerina E.V.Geltser, artists N.V. Kusmin and T.A. Mavrina, I.S. Glazunov, writer V.A. Soloukhin, and tens of others. Their collections, though known only to very narrow circles of friends, were indeed part of the cultural milieu of Soviet Russia, this invisible part of the iceberg which is always bigger than the visible part. Without any doubt, the knowledge about and interest in icons and the artistic taste in the field of icons disseminated in this milieu profoundly influenced the country's cultural life. And this knowledge, which was all the more real for being unofficial, provided a breath of fresh air to the official state research and conservation structures. The State had separated the Church from itself, but a love of ancient icons brought together connoisseurs from the church environment, private collectors of every level of religiosity and those in charge of the State collections.