THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 11 - West of the Iron Curtain

Оригинал взят у mmekourdukova в THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 11 - West of the Iron Curtain

In order to study the Russian iconographic tradition outside Russia, it is worth making the effort to define who it was that transmitted this tradition, what structures served as the link in the chain, and what part of the Russian iconographic treasury was known in Europe at the time. Who then, on leaving Russia, brought the ecclesiastic cultural tradition to the west?

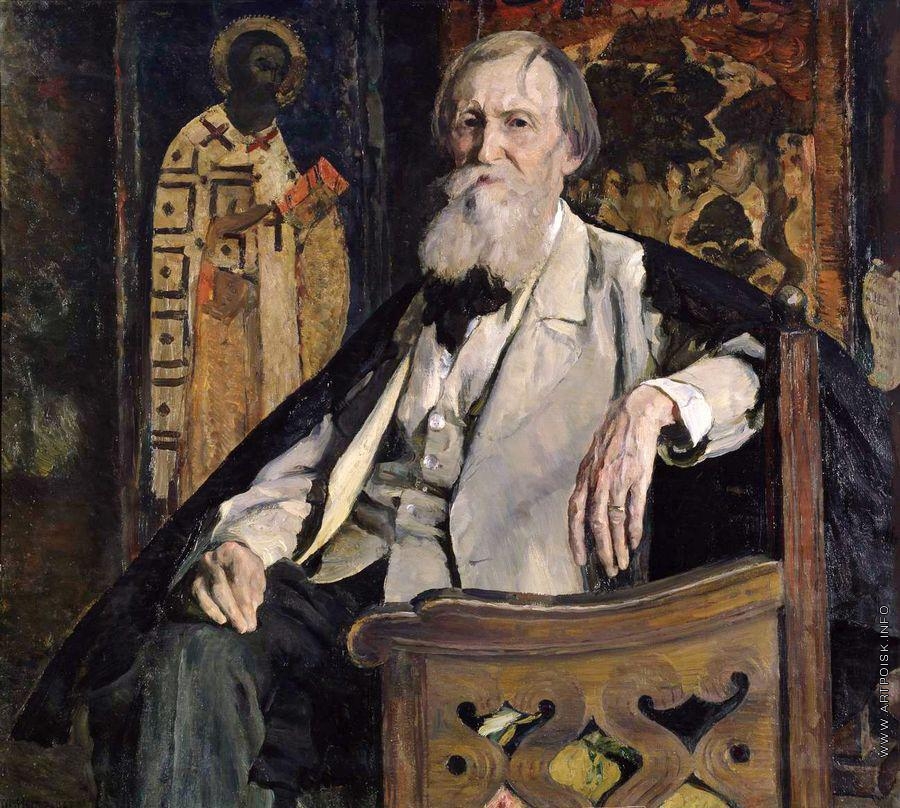

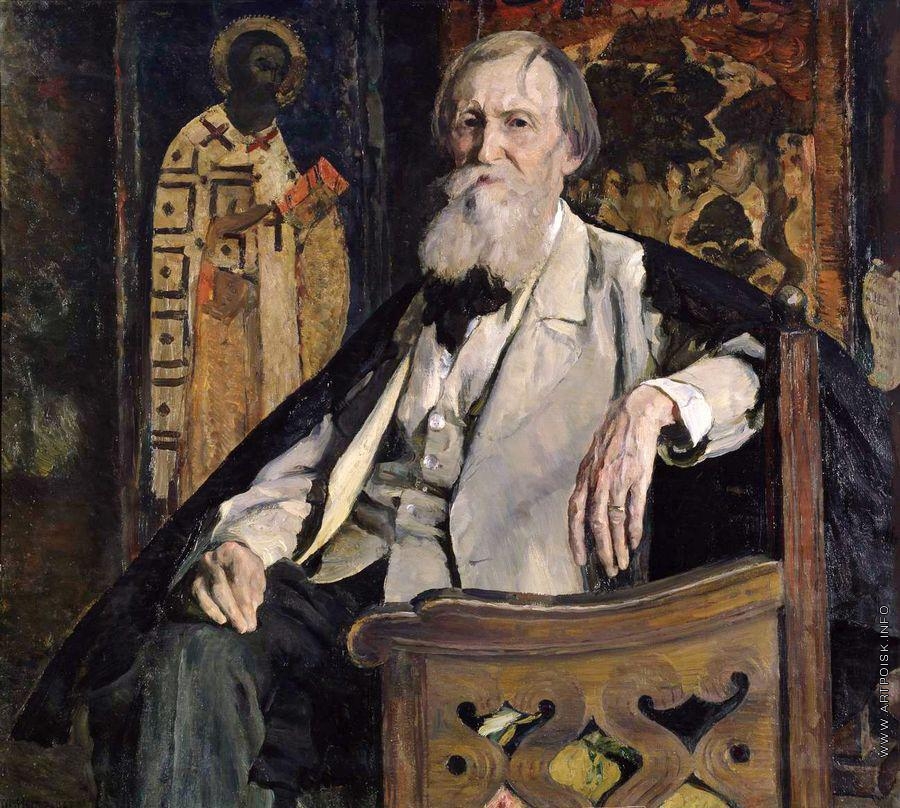

Let us return to the broad picture we sketched in the previous chapter. No high quality Academic artist, known for this work for the Church, left Russia. Viktor Vasnetsov died peacefully in Moscow in 1926, surrounded with well-merited respect. His obituary, published in the national press, mentioned his church works as masterpieces of national genius.[1] Mikhail Nesterov (1862-1942) also remained in Russia, continuing to paint until his death, and enjoying public recognition. A friend of Nesterov, who at the age of 17 had painted with him the monastery of Saints Martha and Mary at Moscow, Pavel Korin (1892-1967), went on to become one of the stars of Soviet painting, as well as one of the greatest connoisseurs and collectors of ancient icons. His collection, even during its owner’s lifetime, received the official status of a branch of the Tretyakov Gallery.

None of the eminent representatives of high level «Byzantine» painting, as we described them in our previous chapter, was among the emigrants. It should be pointed out that the Old Believer artists worked mainly for private collectors, a market which, more focused on the restoration of antiquities or counterfeiting, did not suffer under the new authorities. Some of them were hired by State museums and heritage conservation commissions. For example, the last of a long line of iconographers, the eminent expert in ecclesiastic antiquities G. O. Chirikov (1882-1936), until the Revolution the supplier and restorer of icons to the Russian Museum of Emperor Alexander III, now the Russian Museum, became the head of the Central Icon Restoration Workshop. The other icon restorers Y.I. Bryagin (1882-1943), M.I. Tyulin (1876-1964), P.I. Yukin (1885-1945) continued their activities under the new authorities. Not a single specialist at this level is known of in the emigration, and indeed what field of activity would he have found outside Russia? We have already spoken of the artists from Palekh and other local schools: the political change was to their advantage, and their situation improved after the Revolution.

Should we talk about mass-market icon painting? Even if a few such painters found themselves among the ranks of the émigrés, it is certain that they all quit their profession. Such popular mass production exists where there is a large enough market to support it. Cheap serial hand production was condemned in France as in Russia, not because of persecutions, but through lack of demand. In any event these painters did not take part in the rebirth of the ancient iconographic tradition which began and was carried through by representatives of the first two groups, and indeed mainly by the well-instructed Academic artistics who favored the discovery of the medieval icon. Neither the Academic iconographers, nor the artists of the high quality Byzantine tradition took part in the emigration.

It is true that we find in the emigration savants and collectors of ancient icons, like N. Kondakov (1844 - 1925) or the patron of the arts and collector N. Riabouchinsky (1877 - 1951), but their collections were unable to leave Russia. The presence of connoisseurs and their scientific research could not in itself engender the rebirth of art. This needs artists.

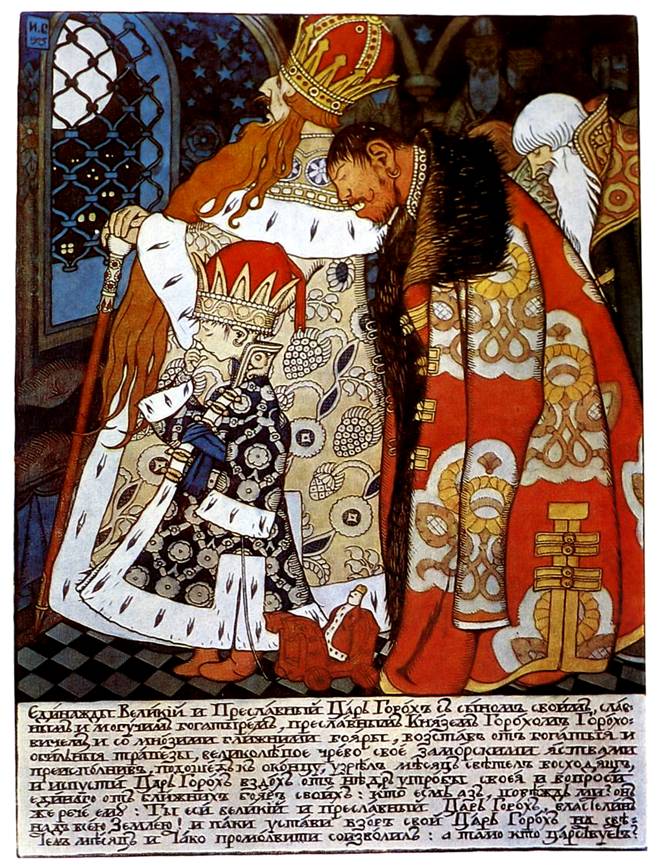

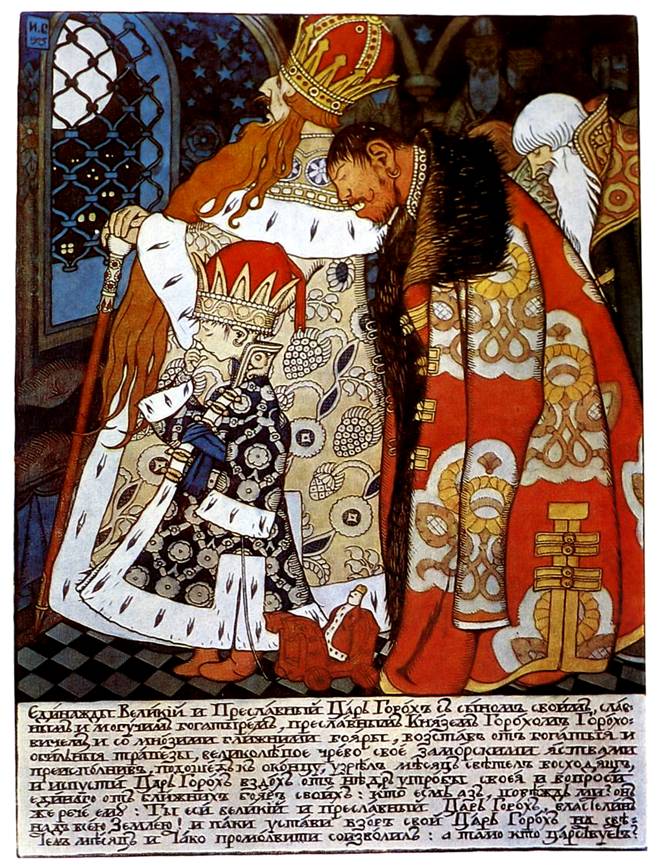

Artists there were in the emigration, a whole pleiade of them, and not the worst, left with the first wave. It would, however, be wrong to compare this exodus with the emigration of Greek artists to western Europe during the iconoclast period or, 700 years later, with the Turkish invasion of Constantinople, to Crete. In those days the iconographers left. In the twentieth century the iconographers stayed in Russia. Those who emigrated were precisely those whose production had nothing to do with icons or was linked the medieval style superficially, aside from the Church and Christianity. Their link with medieval painting was purely at the decorative level, as was that of Nicolay Roerich, whose church the ecclesiastical authorities refused to consecrate, and of Natalia Gontcharova, Ivan Bilibin and Dimitri Stelletsky. The representatives of art nouveau and Russian modernism who ended up in the Paris of the 1920s were very far from the Church, and not only from the viewpoint of their artistic work: they had personally moved away from Christianity. Their private lives, both before and after the Revolution, very far from ascetic, were often, by the criteria of polite society scandalous, and of the church, mortal sin. This is not the place to recite names or deeds: those with a knowledge of Russian period of the «silver age» (end nineteenth century - 1917) know what we are talking about it. Artistic life in those immediately pre-Revolutionary days took place in a near trance-like state, far removed from any spiritual sobriety or moral responsibility, at times clearly diabolic, in that slightly masochistic taste which carries the foreboding of and beckons up catastrophe.

The catastrophe which happened. Most of those who had beckoned it on were buried under the débris, others took flight and emigrated. Not all the survivors sobered up and took the path of repentance. In particular those whose reputation had already preceded them continued their dissolute life in the west. These prominent artists, poets and actors were in no hurry to serve the Church with their talents. Moreover the fees they commanded were quite outside the reach of the cash-strapped émigré parishes.

It is only a pure chance which is explains the only Church commission carried out in Russian emigration circles by a relatively well-known artist. This is the iconostasis and murals of the church of the Institute of Saint Sergius, the theological academy in exile set up in Paris in the property of a former German church sequestrated during World War I. These were painted in the middle of the 1920s by Dimitri Stelletsky (1974-1945). This commission he received through the determination of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, who had accepted to take care of collecting funds for the decoration of the church only on condition that the work be entrusted to Stelletsky, herself donating an emerald of great value she had inherited from the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna. For Stelletsky, then aged 50, this was his first experience of icon painting, although he had long used sacred art as a source of any number of decorative ideas for this theatre decorations, his wood carvings and other exotic-nostalgic projects. It is probably this which led to his being chosen by the Grand Duchess. Visibly, his level of understanding of Orthodox spirituality went no further than his theatre decors. The parallel is striking with the church at Talashkino decorated by Roerich and with his patroness Duchess Tenicheva. In this emigrant situation, could one have set higher standards. The «stage decorations» at Saint Sergius were consecrated all the same although his contemporaries, still filled with memories of true ancient icons, realized the superficiality and approximate nature of Stelletsky's works. For critic S. Makovsky, in his book on the Parnassus of the Silver Age (a significant title if ever there was one), such work is "on the borderlines of dilettantism«.[2] Which is not quite fair. Stelletsky was not a dilettante but a professional artist, and quite a gifted one at that. His dilettantism manifested itself rather in the spiritual domain. Which is why the church of the Saint Sergius Institute received a theatre décor that was totally professional, similar to those that Stelletsky produced for stage settings of Russian works: striking colors, angular silhouettes, patches of light scattered around abundantly... Closer up, from six feet or so, we are struck by a chaotic piling up of badly drawn lines, the blurred drawing, and the mask-like faces which don't really look anywhere. It is amusing to note that the most important part of the work, the faces on the iconostasis, were painted by Duchess E. Lvova, referred to humbly as the Master’s «apprentice». The quality of the painting of these faces is neither better nor worse than what was painted by Stelletsky, though the expression is more human that of the faces painted elsewhere by the master.

This was, therefore, the contribution of a professional artist in the art of the icon for the emigration! This is the work, not only of a professional, but also of a representative of the generation of older artists who had lived nearly half a century in Russia and were undoubtedly interested in medieval art and had enjoyed every opportunity to study it. Such studies were unfortunately only superficial and uncoordinated, directed not by the desire to serve the Church but enslaved to fashion and the search to appear original by using nostalgic decorative inventions. Even if these inventions were placed in a church and consecrated, we cannot see in them the start of the rebirth of the grand Byzantine style.

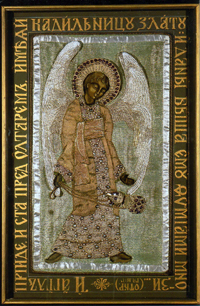

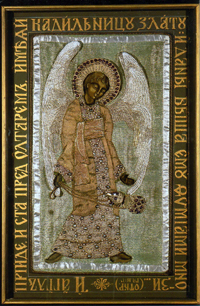

One thing is clear by now: there is no chain linking icon painting outside Russia with the tradition in that country. Outside Russia there was no really qualified iconographer in the Byzantine style, no professional Academician who had worked for the Church before the Revolution, and in particular, no medieval icon, no authentic object, which are the only true carriers of the ancient iconographic tradition.

Even until today, it is easier, in Western Europe, to see a medieval Chinese bronze or a true Egyptian sculpture than a true Russian icon earlier than 1600. And in the 1920s and 1930s, Russian émigrés lived in total isolation from such historical objects. Not a single medieval Russian icon existed in the museums of Western Europe. Private collectors and antiquarian dealers owned a small number of seventeenth and eighteenth century versions. In other words, all that émigrés could view and study as Russian icons was late, not very expressive and of very middling quality. Nor could one even learn medieval Russian painting from reproductions: these were hardly published, and the quality of printed illustrations at the time was unsatisfactory.

All such shortcomings cannot be offset by good intentions or warm enthusiasm. The legend of Kitezhe, the city hidden under a lake, is what pre-Revolutionary Russian culture represented in the west in the early twentieth century. This émigrés believed that they were conserving it, but in fact, this still-existing Kitezhe was hidden from them behind the iron curtain. In no way can the stylistic tradition of «Byzantine» iconography in the Russian emigration be considered either authentic or uninterrupted. The word «tradition» (in the sense of handing down from one generation to another) is out of place here: there is no link in the chain, there is no transmission, no traditio.

Did Russian émigré icon painting ever exist in Western Europe? Without a doubt. But outside the tradition of the Byzantine style. Does any art carry inside it a stylistic tradition that is specific to it? Certainly! Let us therefore try and understand this stylistic tradition of the iconography of the first Russian emigration. From what schools did the representatives of this family of émigré iconographers come? What stylistic influences did they benefit from?

Enter Leonid Uspensky. Aged just 15 at the outbreak of the October Revolution, and the quality of his relations with Orthodox culture of the time can be judged from his voluntary enlistment with the Red Army soon after. Captured by the White Russians, it was only his youth which prevented him being shot, and he left Russia already in 1919 with the White Army. It is not for us to pass judgment the political or spiritual transgressions of this youth, but what is true is that he arrived in France with zero professional training, with no memory of classical Russian icons. A revolutionary adolescent had other interests, and, we repeat again, by the time he left Russia, only a tiny portion of Russia’s medieval masterpieces had been cleaned and made accessible to the general public. It is true that he had good teachers of Academic art, even if he was not able to profit long from them. In the 1930s there existed in Paris a Russian Academy of Fine Arts, the teachers of which were eminent masters. However, this institute did not last long enough for any students to reach graduation. There were not enough Russians in France sufficiently gifted to support the requirements of a good level of art education, and financially able to properly pay the teachers. Neither the Academy’s rector, Konstantin Somov (1869 - 1939), nor Uspensky’s direct teacher, N. Milioti (1874 - 1962) could permit themselves the luxury of teaching art for free, which explains why Uspensky could benefit from their artistic wisdom for two or three years at most. The spirit of this wisdom was the same suave, empoisoned and destructive spirit which reigned in the art in fashion in the declining years of the Russian empire. Milioti was an artificial mannerist, and his paintings and illustrations, with their suffocating medley of gaudy colors, are typical examples of Russian art nouveau. Somov, a more brilliant artist and closer to the classical Academic style, was much more direct in the subjects of his paintings: no slippery equivocation as with Milioti, but openly erotic scenes which were the base of his fame. In the same years as the future iconographer and «icon theologian» Uspensky, with other pupils of the Academy, penetrated their master’s wisdom at Somov’s summer residence in Normandy, Somov himself was working on cycles of seductive illustrations for Manon Lescaut by the Abbé Prévost, Daphnis and Chloé by Longus, and continued to create easel water colors of an incomparable gentleness and meticulousness on erotic, and often homosexual subjects.

It is under this stylistic influence that was formed Vladimir Uspensky, the student of the Academy we are talking of. These same teachers also trained the second major iconographer of the first Russian emigration, G. Krug, later to become Brother Gregory (1908-1969). He left Russia at the age of 13, not only before receiving any professional training, but also before becoming Orthodox. His parents, Swedes from St Petersburg, were Lutheran, a confession which, we know, recognizes neither icons nor holy images. Krug became orthodox in Estonia in 1927 and, four years later, moved to Paris, where he too entered Somov’s Academy. Here begins a Bohemian period of this life, given over entirely to creative research, sharing the life style and doubtful leisure pursuits of his fellow Parisian artists, becoming in particular a close friend of Primitivist Mikhail Larionov, then very much in fashion. All this he combined with his spiritual search, or rather his interest for iconography. But can one talk of serious spiritual search without repentance and change of lifestyle. According to his biographers, Krug learned icon painting from the Old Believers and from Julia Reitlinger, whom we will come back to later. This disharmony between Parisian Bohemian life, passionate and individualist, and sacred art, which calls for interior purification, discipline and peace, was difficult for Krug, by nature nervous and impulsive. But he was unable to break with the first in favor of the second. Finally, in a state of total physical and psychic exhaustion, and prey to terrible hallucinations, he found himself in a mental asylum. This he managed to leave in the late 1940s with the spiritual assistance of Fr Serguei Schevich, who convinced him to become a monk. This decision was undoubtedly salutary for Krug, including for purely material reasons, as our artist was totally irresponsible and incapable of adapting to the world. Brother Gregory remained faithful to himself in his monastic life, but at least he had a roof over his head and food in his plate.

As we see, this artist, facilely billed as a «second Andrei Rublev» and "the last true iconographer"[3] cannot be overly proud of the stylistic tradition in which he was brought up. Not only was this a lay tradition, it is was so totally opposed in spirit to everything that is the Church that its marriage with icon painting brought Krug, sensitive and unbalanced, to a state of mental illness, and was nearly his downfall.

With regard to his icon painting studies with the Old Believers (undertaken, the sources tell us, in the company of Reitlinger and Stelletsky), we would like to raise a certain number of questions.

First and foremost, who were these anonymous Old Believers? They are always mentioned in the plural by Krug's and Reitlinger's biographers, but we have no name and no icon of these enigmatic masters. Yet, if we are talking of the training of a whole group of icon painters by these masters, there has to have been a workshop which was working somewhere, on a commission or open market basis. Why do we find no trace of this fairly recent activity (1930s), which would certainly have been more professional in its approach that those who were taught by it?

Second, what type of Old Believers were these, if they were ready to open up so easily the mysteries of their sacred trade to people whom they had been trained to believe to be heretics condemned to hell, and with whom it is an abomination to share not only prayer but also food? The strict rules of these Old Believers went as far to require separate crockery and cutlery for other Christians. On top of this, our apprentice iconographers were not only heretics, but Stelletsky painted theater décors, Krug was a Bohemian, and Reitlinger an independent-minded young lady.

Third: where are the traces of this mysterious training in the creative work of these three authors? Even if they had no intention of following the dry, rigid style of late Old Believer icons, where are the undoubtedly good and useful things that any iconographer can take away from this school? Where do we find this professional refinement, this strict discipline of decorative drawing? Where do we find his unrivalled elegance of fine lines and gentle shading? Nothing of the sort can be found in Stelletsky, whose style we have described above, nor in Krug, and even less so in Reitlinger. Even the purely technical side of their work is totally opposed to the tradition of the Old Believers. Where are the carefully worked boards? Where is the mirror-smooth levkas ground? Where are the durable colors and the solid, clean olifa varnish? Instead of all this, their boards are brutally planed and crudely hollowed out, the ground is uneven, the varnish of poor quality, patchy and with blackened spots, craquelures, paint and levkas losses, colors which have either darkened or faded with time. Visibly, the much-vaunted iconographers of the first emigration were very poor pupils!

What seems to us more probable is that their entire training consisted of consulting with and obtaining advice from the undemanding specialists who worked, not for the Church, but by the rich and large Paris antiquarian market. The attempts to present these fleeting and fruitless contacts with these anonymous Old Believers as serious training is no more than an unsuccessful myth. Of Reitlinger one commentator writes: "She perfectly mastered the trade of iconographer, having been trained with the Old Believers.«[4] Of Reitlinger we also know that she took lessons from Stelletsky and gave lessons to Krug. Truly ridiculous and pitiful are all these attempts to compose a genealogical tree for each person turning in this minuscule and isolated circle of first emigration iconographers. They could learn anything they wanted from each other, but that did not make their work traditional. The only stylistic tradition to which they all belonged, the only professional school through which they had passed, was the lay, Academic school. Not only Academic in its neutral sense, as we can speak of the public academies in Europe, but penetrated by a spirit of decadence, moral impurity and laisser-aller.

Krug paid dearly for this training. His ability to paint and draw received from Somov and Milioti he paid for with an interior imbalance and mental illness from his youth, an imbalance he was never to overcome until his death. While, certainly this art therapy imposed by Father Serguei Schevitch had some healing effect, attacks of Angst, a tortured awareness of his creative incapacity, alternating with paroxysms of artistic self-expression, were normal soul states for Brother Gregory. No peace or joy appears through in his icons. His figures suffer, are tortured, plunged in the Angst of sin and the imperfection of this world. There is no doubt that, in normal conditions, Brother Gregory would never have been allowed to «preach in pictures». In the best of cases, by the condescendence for the insatiable desire of an inwardly deeply wounded man to express himself artistically, he would have received permission to work in the workshop of a spiritually more mature master who had already reached a level of interior peace.

Uspensky, psychologically more stable, was better able to resist the poison of the school he attended, being more balanced and solid in both his personal life and his icon painting. But on the other hand, what hate for the school that trained him exudes from his writings! He takes his vengeance on the gentle Nesterov, on the pure-souled Vatsnetsov, pouring out over them all his meanness against the stylistic tradition in which he had been brought up. Absolutely convinced of its decadence, he aims his thunderbolts at it, building his entire surprising theology of the icon, and like an ungrateful son, denying and reviling this same Academic tradition in which he had been trained.

This artistic filiation is in fact expressed in his professionalism: his icons and carved panels are relatively firmly drawn, one senses his feel for anatomy, he knows how to sculpt shapes with light and shadow, to transmit the appearance and character of his models - knowledge totally absent from the pupils who confidently followed his advice. Secondly, Uspensky’s filiation to the Academic tradition is expressed in the fact that it is this tradition that serves as the alpha and omega of all his «theological» constructions. He is totally unable to explain the artistic language of the icon starting from the icon itself, as if medieval artists’ sole care was, with all their strength, to deny and overturn the style that appeared centuries later.

All this confirms yet again the axiom known of any theoretician of the Fine Arts. We will express it by paraphrasing a popular Russian saying: «your wife is not an old sock», which means that you can't cast it off that easily, to «tradition is not an old sock». It is only with major efforts that we can move away from our aesthetic stereotypes and replace them, little by little, with new ones. This work is very comparable with that of the spiritual path of the purification of the heart from sin and passions. First of all of the heavy sins and passions and then, as the moral sensitivity grows, of secondary sins, and finally of sinful thoughts. This spiritual path is much simpler under the direction of an experienced spiritual father, or at least supported by good spiritual reading. In the same way, the purification of a style from spiritually negative elements is much easier under the direction of an experienced master in the art (not in the profession) or by contemplating classical samples of a better style.

The iconographers of the first emigration had neither the one nor the other. This is why, searching for a proper style for the icon, they rejected the Academic tradition in such a tortured, clumsy and convulsive fashion.

Much more reasonable would have been, having first been trained in a serious professional school, not to reject it for a nostalgic myth, but to try humbly, within the available framework, to achieve a true Orthodox spirituality, all the more so as such a tradition already existed in Russian art. Neither Uspensky nor Krug was ready, however, to take this path.

Reitlinger, later Sister Ioanna, did make an attempt in this direction. She was quickly disappointed by Stelletsky and the above-mentioned anonymous Old Believers and, in general, did not find it necessary to remain within the narrow confines of this little marginal world of the Russian school in Paris. She began taking lessons with a well-known French painter who worked on Church commissions, surrounded by dozens of monumental works and paintings of religious subjects. Maurice Denis (1870 - 1943), though hardly an iconographer in the Orthodox sense of the term, was an artist of eminent merit in the Catholic artistic school, who succeeded in reviving and breathing new life into and raising to another level Catholic religious imagery, the boring and sugary style of which was very close to that of the craft-Academic Russian icons of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In Denis’s paintings and panels one senses a genuine mystical flame, a hymn to the grace of the Creation, a warm appreciation of the contemplation of this beautiful, sun-drenched world where there are so many flowers, chaste girls and chubby-cheeked babies singing the Lord's praises in joyful accord. Although formally part of the art nouveau movement, Denis is undoubtedly head and shoulders above the general level of this spiritually destructive individualist and mannerist world. Denis was one of the very small number of those who succeeded in moving behind the decadent and poisoned spirit of their time to affirm beauty, life and goodness in the apparently typical shapes of Art nouveau.

Even so, what was excellent as decoration for Catholic churches, did not englobe the full Orthodox plenitude of the knowledge of God. One senses a certain lack in Denis's tender, gentle figures in their bourgeois, paradisiacal glasshouses. They do not belong beside the figures of orthodox iconography who regard the spectator in the eye with wisdom, virility, concentration, virtue and love. Reitlinger felt this too, and after three years she left Denis, and with him perhaps the only school imbued with a Christian spirit and a high level of professionalism existing in the Paris of her day, disappointed and unhappy. She began her own research. This research was beyond the strength of a young girl who was neither particularly gifted nor sufficiently trained.

It is possible that if Reitlinger had had the humility to achieve first of all a certain level of professionalism under Denis’s direction and, then purifying, ennobling and correcting her style, had made it suitable for expression the truth of Orthodoxy, she would have become a decent iconographer, though not in the Byzantine style. This, unfortunately, was not to be. The cause almost certainly lay in this militant absolutization of the Byzantine style, this suffocating nostalgic atmosphere which pushed the iconographers of the first emigration to create a tradition out of nothing. And really out of nothing: Reitlinger’s only exposure to the traditional Russian icon was at the exhibition of the Soviet museums of ancient Russian art which was held in Munich in 1928. In order to look once at works accessible then to any Soviet citizen, she was forced to cross half of Europe and sacrifice a sum of money well beyond her poor resources. But to see such works, and even to sketch them in an exhibition hall, is not the same as mastering the tradition. The impressions she left with were enough to disappoint her of the lessons of both the Old Believers and Maurice Denis, but not to master the style of the medieval iconographers.

Reitlinger’s subsequent - and long - creative biography shows her flitting about in a search for what she herself called the «creative icon». This naive pleonasm did not offend the ears either of Sister Ioanna or her circle. Visibly, they were accustomed to think that the icon, in itself, is not creative at all, and that it is only under the brush of Sister Ioanna that it becomes creative.

Flitting from the stylization to the realistic treatment of shapes, from whitish to dull tones, from sugary sweet rendering to a forced brutality, from canonical iconography to an «iconography» not worthy of this name, Sister Ioanna painted abundantly and in a very varied manner. But never in the tradition, and never in an artistically professional manner. It is amusing to note that the only stable feature of her works is a certain taste for late art nouveau: weak colors, rounded, apathetic silhouettes, like a worn piece of soap. Tired, hesitant lines like the steps of marsh plants, cotton wool faces, bespeaking the influence of Denis or rather a superficial imitation of his style. The master himself did not abuse the tricks of art nouveau and his mature works move beyond the mannerism and typical apathies of this early works, but his pupil remained marked for life by the Paris fashion of the twenties and thirties.

It should be added that Sister Ioanna returned to Russia after World War II with the blessing of Fr Serge Bulgakov. She was in no way involved with the renaissance of the ancient painting tradition in Russia and her «creative» icon found no application in the Church. During the same period her contemporary Mother Juliania - both were born in 1899 - was directing with an experienced hand the restoration work at the Saint Sergius Lavra, founded an icon school, painted icons, wrote icons and books. Sister Ioanna remained on the furthest periphery of Church art. Forced, to earn her keep, to paint scarves in a textile factory, she continued to paint from time to time little icons as presents for her friends. In other words, in the conditions of the true artistic and spiritual tradition of the icon, Reitlinger's creativity received the status it deserved, that of hobby painting.

Let us not ask what role either Uspensky or Krug would have played in the renaissance of the grand Byzantine style if they too had returned to Russia in the 1940s. We prefer to stay with the facts. We do have some indications to go on: among the tens of thousands of icon reproductions published in Russia in recent decades, we find not a single work by these authors. What are published are the icons of Mother Juliania, Father Zinon, Natalia Aldoshina and Sergei Fyodorov and hundreds of other contemporary iconographers, including both real artists and simple artisans. But the creativity of Uspensky and Krug, the two most eminent representatives of the first emigration, are not in demand.

There is no need to mention here the names of those who were less eminent. The artistic level of their production is such that it excludes any possibility of speaking of it as art, of trying to define any stylistic particularities, any tradition ..... One cannot speak of this production, even under the title of traditional craftwork, like one can of popular images or bronze crosses and objets de dévotion.

One cannot seriously talk of a phenomenon of artisanal art work, like brass crosses or matriochkas, without there being at least a hundred or so artisans per village who have painted these matriochkas, in artisan fashion, for fifty years at least. It is important that Ivan paints better matriochkas than Boris and therefore sells them better, and that Boris then tries with all his strength to be better than Ivan, and in that way takes place - albeit in this lowly and brutal art form - the eternal miracle which has ever taken place in true art: the artist’s effort to achieve beauty, and to have this beauty accepted by society, the honest competition of artists searching for perfection, the appearance and development of the school and the tradition, communion and agreement between artists and spectators on what is beautiful and good. Is this what happened with the iconography of the first generation? The answer, alas, is no. As late as the 1960s, Archimandrite Kyprian Pyzhov defined the main difference between Russian iconography and that of the emigration that in Russian icon painting, «as in any other profession, some were better qualified than others, but there was always the training of the craft profession which distinguished any icon painted in Russia from the work practiced abroad. (......) The Russia of the emigration was unable to attain this craft level. Those who imitate the ancient manner without understanding its main merit, its ability to express the spiritual content of the objects painted, and who instead focus attention on «incorrectnesses», that is on the contradictions with a realistic reading, seeing this as the principal and most important feature of this type of work, reinforcing in these «false antiquities» those incorrectnesses which would best have been avoided.«[5]

Summarizing our review of the school and tradition in the iconography of the emigration, one has to conclude that:

a. Even the most eminent, professional or semi-professional iconographers hardly belonged to the traditional icon school. Their creativity, albeit expressing to a certain extent the Orthodox idea of deified man, remained all the same a unique, isolated phenomenon in sacred art, in fact a cul-de-sac. The small number of iconographers of a high level who are working today in Western Europe owe their artistic professionalism to direct contacts with Russia, to the availability nowadays of information on classical medieval icon painting. They certainly do not owe it to the «tradition» of Krug or Reitlinger, not to the «theology» of Uspensky.

b. Outside this group, which in fact was not even a group but a handful of artists working in relative isolation, very different in style and their understanding of the meaning of the icon, in their lifestyles and their destiny, out of range of the real professionals, the iconography of the first generation in Western Europe was not even artisanal artwork, but simply dilettante tinkering. Dilettante, not only at the artistic level, but also at that of the knowledge of canonical iconography and basic theological sentiment. What do we say of people, like Mother (later Saint) Maria Skobtsova ,who use Vroubel's works as models for their icons? Or this new type of icon, by the same painter, of the Mother of God with a little crucifix in her hand figuring a live baby Christ Child?[6] Or of the icon of Sophia, Divine Wisdom, at table with the «New Martyrs of Paris», which is part of the festival of mediocre icon painting, widely disseminated on the internet, following the canonization of the same Mother Maria?[7]

This dilettante and irresponsible approach to the art of the icon has been made possible and has struck even deeper roots since because the theoretical basis justifying it (Leonid Uspensky's «Theology of the Icon» - originally published in French in 1960 under the humbler title «Essay on the Theology of the Icon in the Orthodox Church») was not slow to appear and is seen still today by certain people as unshakeable, even if today it is good tone (in particular if one is not too close to the Church) to speak of the icon in the spirit of certain superstitious agnosticism.

We should also note that the fact that an icon is blessed and thereby becomes a sacred object engenders two phenomena. The first is a taboo against identifying it with a work of art, and therefore removing it from any basic artistic exigencies. The second is the notion that anyone who wants to paint icons can. Together this produces a fateful mixture: zero aesthetic exigency and a cartload of spirituality. Any aesthetic judgment of an icon is considered indecent, whilst dilettante iconography is deemed permissible and even praiseworthy. We have already spoken sufficiently of the indecency of penetrating the spiritual field through the production of cheap little Byzantine images. We shall now go on in the next chapter to look at how the icon lives and acts in the Church, what are the mystical and aesthetic sides to this life, and how the people of God, brought up in the true tradition of Christian art, knows how to distinguish good iconography from bad.

[1] Viktor Vasnetsov, Pisma. Noviya materiali, St Petersburg 2004, pp. 301-303

[2] Quoted in: Irina Yazikova, «Se tvoryu vso novoye» : Ikona v XX veke. La Casa di Matriona, 2002, p. 29

[3] Cited by Irina Yazikova, «Se tvoryu vso novoye» : Ikona v XX veke. La Casa di Matriona, 2002, p. 51

[4] Natalia Bolshakova, Khristianstvo osushestvimo na zemle, Riga, 2006, p. 98

[5] Archimandrite Kyprian Pyzhov K poznaniyu pravoslavnoye ikonopisi «Pravoslavnaya Zhizn», Jourdainville, 1966, no. 1, pp. 8-13;

[6] Irina Yazikova, «Se tvoryu vso novoye» : Ikona v XX veke. La Casa di Matriona, 2002, p. 32

[7] http://www.flickr.com/photos/jimforest/sets/164907/

In order to study the Russian iconographic tradition outside Russia, it is worth making the effort to define who it was that transmitted this tradition, what structures served as the link in the chain, and what part of the Russian iconographic treasury was known in Europe at the time. Who then, on leaving Russia, brought the ecclesiastic cultural tradition to the west?

Let us return to the broad picture we sketched in the previous chapter. No high quality Academic artist, known for this work for the Church, left Russia. Viktor Vasnetsov died peacefully in Moscow in 1926, surrounded with well-merited respect. His obituary, published in the national press, mentioned his church works as masterpieces of national genius.[1] Mikhail Nesterov (1862-1942) also remained in Russia, continuing to paint until his death, and enjoying public recognition. A friend of Nesterov, who at the age of 17 had painted with him the monastery of Saints Martha and Mary at Moscow, Pavel Korin (1892-1967), went on to become one of the stars of Soviet painting, as well as one of the greatest connoisseurs and collectors of ancient icons. His collection, even during its owner’s lifetime, received the official status of a branch of the Tretyakov Gallery.

None of the eminent representatives of high level «Byzantine» painting, as we described them in our previous chapter, was among the emigrants. It should be pointed out that the Old Believer artists worked mainly for private collectors, a market which, more focused on the restoration of antiquities or counterfeiting, did not suffer under the new authorities. Some of them were hired by State museums and heritage conservation commissions. For example, the last of a long line of iconographers, the eminent expert in ecclesiastic antiquities G. O. Chirikov (1882-1936), until the Revolution the supplier and restorer of icons to the Russian Museum of Emperor Alexander III, now the Russian Museum, became the head of the Central Icon Restoration Workshop. The other icon restorers Y.I. Bryagin (1882-1943), M.I. Tyulin (1876-1964), P.I. Yukin (1885-1945) continued their activities under the new authorities. Not a single specialist at this level is known of in the emigration, and indeed what field of activity would he have found outside Russia? We have already spoken of the artists from Palekh and other local schools: the political change was to their advantage, and their situation improved after the Revolution.

Should we talk about mass-market icon painting? Even if a few such painters found themselves among the ranks of the émigrés, it is certain that they all quit their profession. Such popular mass production exists where there is a large enough market to support it. Cheap serial hand production was condemned in France as in Russia, not because of persecutions, but through lack of demand. In any event these painters did not take part in the rebirth of the ancient iconographic tradition which began and was carried through by representatives of the first two groups, and indeed mainly by the well-instructed Academic artistics who favored the discovery of the medieval icon. Neither the Academic iconographers, nor the artists of the high quality Byzantine tradition took part in the emigration.

It is true that we find in the emigration savants and collectors of ancient icons, like N. Kondakov (1844 - 1925) or the patron of the arts and collector N. Riabouchinsky (1877 - 1951), but their collections were unable to leave Russia. The presence of connoisseurs and their scientific research could not in itself engender the rebirth of art. This needs artists.

Artists there were in the emigration, a whole pleiade of them, and not the worst, left with the first wave. It would, however, be wrong to compare this exodus with the emigration of Greek artists to western Europe during the iconoclast period or, 700 years later, with the Turkish invasion of Constantinople, to Crete. In those days the iconographers left. In the twentieth century the iconographers stayed in Russia. Those who emigrated were precisely those whose production had nothing to do with icons or was linked the medieval style superficially, aside from the Church and Christianity. Their link with medieval painting was purely at the decorative level, as was that of Nicolay Roerich, whose church the ecclesiastical authorities refused to consecrate, and of Natalia Gontcharova, Ivan Bilibin and Dimitri Stelletsky. The representatives of art nouveau and Russian modernism who ended up in the Paris of the 1920s were very far from the Church, and not only from the viewpoint of their artistic work: they had personally moved away from Christianity. Their private lives, both before and after the Revolution, very far from ascetic, were often, by the criteria of polite society scandalous, and of the church, mortal sin. This is not the place to recite names or deeds: those with a knowledge of Russian period of the «silver age» (end nineteenth century - 1917) know what we are talking about it. Artistic life in those immediately pre-Revolutionary days took place in a near trance-like state, far removed from any spiritual sobriety or moral responsibility, at times clearly diabolic, in that slightly masochistic taste which carries the foreboding of and beckons up catastrophe.

The catastrophe which happened. Most of those who had beckoned it on were buried under the débris, others took flight and emigrated. Not all the survivors sobered up and took the path of repentance. In particular those whose reputation had already preceded them continued their dissolute life in the west. These prominent artists, poets and actors were in no hurry to serve the Church with their talents. Moreover the fees they commanded were quite outside the reach of the cash-strapped émigré parishes.

It is only a pure chance which is explains the only Church commission carried out in Russian emigration circles by a relatively well-known artist. This is the iconostasis and murals of the church of the Institute of Saint Sergius, the theological academy in exile set up in Paris in the property of a former German church sequestrated during World War I. These were painted in the middle of the 1920s by Dimitri Stelletsky (1974-1945). This commission he received through the determination of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, who had accepted to take care of collecting funds for the decoration of the church only on condition that the work be entrusted to Stelletsky, herself donating an emerald of great value she had inherited from the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna. For Stelletsky, then aged 50, this was his first experience of icon painting, although he had long used sacred art as a source of any number of decorative ideas for this theatre decorations, his wood carvings and other exotic-nostalgic projects. It is probably this which led to his being chosen by the Grand Duchess. Visibly, his level of understanding of Orthodox spirituality went no further than his theatre decors. The parallel is striking with the church at Talashkino decorated by Roerich and with his patroness Duchess Tenicheva. In this emigrant situation, could one have set higher standards. The «stage decorations» at Saint Sergius were consecrated all the same although his contemporaries, still filled with memories of true ancient icons, realized the superficiality and approximate nature of Stelletsky's works. For critic S. Makovsky, in his book on the Parnassus of the Silver Age (a significant title if ever there was one), such work is "on the borderlines of dilettantism«.[2] Which is not quite fair. Stelletsky was not a dilettante but a professional artist, and quite a gifted one at that. His dilettantism manifested itself rather in the spiritual domain. Which is why the church of the Saint Sergius Institute received a theatre décor that was totally professional, similar to those that Stelletsky produced for stage settings of Russian works: striking colors, angular silhouettes, patches of light scattered around abundantly... Closer up, from six feet or so, we are struck by a chaotic piling up of badly drawn lines, the blurred drawing, and the mask-like faces which don't really look anywhere. It is amusing to note that the most important part of the work, the faces on the iconostasis, were painted by Duchess E. Lvova, referred to humbly as the Master’s «apprentice». The quality of the painting of these faces is neither better nor worse than what was painted by Stelletsky, though the expression is more human that of the faces painted elsewhere by the master.

This was, therefore, the contribution of a professional artist in the art of the icon for the emigration! This is the work, not only of a professional, but also of a representative of the generation of older artists who had lived nearly half a century in Russia and were undoubtedly interested in medieval art and had enjoyed every opportunity to study it. Such studies were unfortunately only superficial and uncoordinated, directed not by the desire to serve the Church but enslaved to fashion and the search to appear original by using nostalgic decorative inventions. Even if these inventions were placed in a church and consecrated, we cannot see in them the start of the rebirth of the grand Byzantine style.

One thing is clear by now: there is no chain linking icon painting outside Russia with the tradition in that country. Outside Russia there was no really qualified iconographer in the Byzantine style, no professional Academician who had worked for the Church before the Revolution, and in particular, no medieval icon, no authentic object, which are the only true carriers of the ancient iconographic tradition.

Even until today, it is easier, in Western Europe, to see a medieval Chinese bronze or a true Egyptian sculpture than a true Russian icon earlier than 1600. And in the 1920s and 1930s, Russian émigrés lived in total isolation from such historical objects. Not a single medieval Russian icon existed in the museums of Western Europe. Private collectors and antiquarian dealers owned a small number of seventeenth and eighteenth century versions. In other words, all that émigrés could view and study as Russian icons was late, not very expressive and of very middling quality. Nor could one even learn medieval Russian painting from reproductions: these were hardly published, and the quality of printed illustrations at the time was unsatisfactory.

All such shortcomings cannot be offset by good intentions or warm enthusiasm. The legend of Kitezhe, the city hidden under a lake, is what pre-Revolutionary Russian culture represented in the west in the early twentieth century. This émigrés believed that they were conserving it, but in fact, this still-existing Kitezhe was hidden from them behind the iron curtain. In no way can the stylistic tradition of «Byzantine» iconography in the Russian emigration be considered either authentic or uninterrupted. The word «tradition» (in the sense of handing down from one generation to another) is out of place here: there is no link in the chain, there is no transmission, no traditio.

Did Russian émigré icon painting ever exist in Western Europe? Without a doubt. But outside the tradition of the Byzantine style. Does any art carry inside it a stylistic tradition that is specific to it? Certainly! Let us therefore try and understand this stylistic tradition of the iconography of the first Russian emigration. From what schools did the representatives of this family of émigré iconographers come? What stylistic influences did they benefit from?

Enter Leonid Uspensky. Aged just 15 at the outbreak of the October Revolution, and the quality of his relations with Orthodox culture of the time can be judged from his voluntary enlistment with the Red Army soon after. Captured by the White Russians, it was only his youth which prevented him being shot, and he left Russia already in 1919 with the White Army. It is not for us to pass judgment the political or spiritual transgressions of this youth, but what is true is that he arrived in France with zero professional training, with no memory of classical Russian icons. A revolutionary adolescent had other interests, and, we repeat again, by the time he left Russia, only a tiny portion of Russia’s medieval masterpieces had been cleaned and made accessible to the general public. It is true that he had good teachers of Academic art, even if he was not able to profit long from them. In the 1930s there existed in Paris a Russian Academy of Fine Arts, the teachers of which were eminent masters. However, this institute did not last long enough for any students to reach graduation. There were not enough Russians in France sufficiently gifted to support the requirements of a good level of art education, and financially able to properly pay the teachers. Neither the Academy’s rector, Konstantin Somov (1869 - 1939), nor Uspensky’s direct teacher, N. Milioti (1874 - 1962) could permit themselves the luxury of teaching art for free, which explains why Uspensky could benefit from their artistic wisdom for two or three years at most. The spirit of this wisdom was the same suave, empoisoned and destructive spirit which reigned in the art in fashion in the declining years of the Russian empire. Milioti was an artificial mannerist, and his paintings and illustrations, with their suffocating medley of gaudy colors, are typical examples of Russian art nouveau. Somov, a more brilliant artist and closer to the classical Academic style, was much more direct in the subjects of his paintings: no slippery equivocation as with Milioti, but openly erotic scenes which were the base of his fame. In the same years as the future iconographer and «icon theologian» Uspensky, with other pupils of the Academy, penetrated their master’s wisdom at Somov’s summer residence in Normandy, Somov himself was working on cycles of seductive illustrations for Manon Lescaut by the Abbé Prévost, Daphnis and Chloé by Longus, and continued to create easel water colors of an incomparable gentleness and meticulousness on erotic, and often homosexual subjects.

It is under this stylistic influence that was formed Vladimir Uspensky, the student of the Academy we are talking of. These same teachers also trained the second major iconographer of the first Russian emigration, G. Krug, later to become Brother Gregory (1908-1969). He left Russia at the age of 13, not only before receiving any professional training, but also before becoming Orthodox. His parents, Swedes from St Petersburg, were Lutheran, a confession which, we know, recognizes neither icons nor holy images. Krug became orthodox in Estonia in 1927 and, four years later, moved to Paris, where he too entered Somov’s Academy. Here begins a Bohemian period of this life, given over entirely to creative research, sharing the life style and doubtful leisure pursuits of his fellow Parisian artists, becoming in particular a close friend of Primitivist Mikhail Larionov, then very much in fashion. All this he combined with his spiritual search, or rather his interest for iconography. But can one talk of serious spiritual search without repentance and change of lifestyle. According to his biographers, Krug learned icon painting from the Old Believers and from Julia Reitlinger, whom we will come back to later. This disharmony between Parisian Bohemian life, passionate and individualist, and sacred art, which calls for interior purification, discipline and peace, was difficult for Krug, by nature nervous and impulsive. But he was unable to break with the first in favor of the second. Finally, in a state of total physical and psychic exhaustion, and prey to terrible hallucinations, he found himself in a mental asylum. This he managed to leave in the late 1940s with the spiritual assistance of Fr Serguei Schevich, who convinced him to become a monk. This decision was undoubtedly salutary for Krug, including for purely material reasons, as our artist was totally irresponsible and incapable of adapting to the world. Brother Gregory remained faithful to himself in his monastic life, but at least he had a roof over his head and food in his plate.

As we see, this artist, facilely billed as a «second Andrei Rublev» and "the last true iconographer"[3] cannot be overly proud of the stylistic tradition in which he was brought up. Not only was this a lay tradition, it is was so totally opposed in spirit to everything that is the Church that its marriage with icon painting brought Krug, sensitive and unbalanced, to a state of mental illness, and was nearly his downfall.

With regard to his icon painting studies with the Old Believers (undertaken, the sources tell us, in the company of Reitlinger and Stelletsky), we would like to raise a certain number of questions.

First and foremost, who were these anonymous Old Believers? They are always mentioned in the plural by Krug's and Reitlinger's biographers, but we have no name and no icon of these enigmatic masters. Yet, if we are talking of the training of a whole group of icon painters by these masters, there has to have been a workshop which was working somewhere, on a commission or open market basis. Why do we find no trace of this fairly recent activity (1930s), which would certainly have been more professional in its approach that those who were taught by it?

Second, what type of Old Believers were these, if they were ready to open up so easily the mysteries of their sacred trade to people whom they had been trained to believe to be heretics condemned to hell, and with whom it is an abomination to share not only prayer but also food? The strict rules of these Old Believers went as far to require separate crockery and cutlery for other Christians. On top of this, our apprentice iconographers were not only heretics, but Stelletsky painted theater décors, Krug was a Bohemian, and Reitlinger an independent-minded young lady.

Third: where are the traces of this mysterious training in the creative work of these three authors? Even if they had no intention of following the dry, rigid style of late Old Believer icons, where are the undoubtedly good and useful things that any iconographer can take away from this school? Where do we find this professional refinement, this strict discipline of decorative drawing? Where do we find his unrivalled elegance of fine lines and gentle shading? Nothing of the sort can be found in Stelletsky, whose style we have described above, nor in Krug, and even less so in Reitlinger. Even the purely technical side of their work is totally opposed to the tradition of the Old Believers. Where are the carefully worked boards? Where is the mirror-smooth levkas ground? Where are the durable colors and the solid, clean olifa varnish? Instead of all this, their boards are brutally planed and crudely hollowed out, the ground is uneven, the varnish of poor quality, patchy and with blackened spots, craquelures, paint and levkas losses, colors which have either darkened or faded with time. Visibly, the much-vaunted iconographers of the first emigration were very poor pupils!

What seems to us more probable is that their entire training consisted of consulting with and obtaining advice from the undemanding specialists who worked, not for the Church, but by the rich and large Paris antiquarian market. The attempts to present these fleeting and fruitless contacts with these anonymous Old Believers as serious training is no more than an unsuccessful myth. Of Reitlinger one commentator writes: "She perfectly mastered the trade of iconographer, having been trained with the Old Believers.«[4] Of Reitlinger we also know that she took lessons from Stelletsky and gave lessons to Krug. Truly ridiculous and pitiful are all these attempts to compose a genealogical tree for each person turning in this minuscule and isolated circle of first emigration iconographers. They could learn anything they wanted from each other, but that did not make their work traditional. The only stylistic tradition to which they all belonged, the only professional school through which they had passed, was the lay, Academic school. Not only Academic in its neutral sense, as we can speak of the public academies in Europe, but penetrated by a spirit of decadence, moral impurity and laisser-aller.

Krug paid dearly for this training. His ability to paint and draw received from Somov and Milioti he paid for with an interior imbalance and mental illness from his youth, an imbalance he was never to overcome until his death. While, certainly this art therapy imposed by Father Serguei Schevitch had some healing effect, attacks of Angst, a tortured awareness of his creative incapacity, alternating with paroxysms of artistic self-expression, were normal soul states for Brother Gregory. No peace or joy appears through in his icons. His figures suffer, are tortured, plunged in the Angst of sin and the imperfection of this world. There is no doubt that, in normal conditions, Brother Gregory would never have been allowed to «preach in pictures». In the best of cases, by the condescendence for the insatiable desire of an inwardly deeply wounded man to express himself artistically, he would have received permission to work in the workshop of a spiritually more mature master who had already reached a level of interior peace.

Uspensky, psychologically more stable, was better able to resist the poison of the school he attended, being more balanced and solid in both his personal life and his icon painting. But on the other hand, what hate for the school that trained him exudes from his writings! He takes his vengeance on the gentle Nesterov, on the pure-souled Vatsnetsov, pouring out over them all his meanness against the stylistic tradition in which he had been brought up. Absolutely convinced of its decadence, he aims his thunderbolts at it, building his entire surprising theology of the icon, and like an ungrateful son, denying and reviling this same Academic tradition in which he had been trained.

This artistic filiation is in fact expressed in his professionalism: his icons and carved panels are relatively firmly drawn, one senses his feel for anatomy, he knows how to sculpt shapes with light and shadow, to transmit the appearance and character of his models - knowledge totally absent from the pupils who confidently followed his advice. Secondly, Uspensky’s filiation to the Academic tradition is expressed in the fact that it is this tradition that serves as the alpha and omega of all his «theological» constructions. He is totally unable to explain the artistic language of the icon starting from the icon itself, as if medieval artists’ sole care was, with all their strength, to deny and overturn the style that appeared centuries later.

All this confirms yet again the axiom known of any theoretician of the Fine Arts. We will express it by paraphrasing a popular Russian saying: «your wife is not an old sock», which means that you can't cast it off that easily, to «tradition is not an old sock». It is only with major efforts that we can move away from our aesthetic stereotypes and replace them, little by little, with new ones. This work is very comparable with that of the spiritual path of the purification of the heart from sin and passions. First of all of the heavy sins and passions and then, as the moral sensitivity grows, of secondary sins, and finally of sinful thoughts. This spiritual path is much simpler under the direction of an experienced spiritual father, or at least supported by good spiritual reading. In the same way, the purification of a style from spiritually negative elements is much easier under the direction of an experienced master in the art (not in the profession) or by contemplating classical samples of a better style.

The iconographers of the first emigration had neither the one nor the other. This is why, searching for a proper style for the icon, they rejected the Academic tradition in such a tortured, clumsy and convulsive fashion.

Much more reasonable would have been, having first been trained in a serious professional school, not to reject it for a nostalgic myth, but to try humbly, within the available framework, to achieve a true Orthodox spirituality, all the more so as such a tradition already existed in Russian art. Neither Uspensky nor Krug was ready, however, to take this path.

Reitlinger, later Sister Ioanna, did make an attempt in this direction. She was quickly disappointed by Stelletsky and the above-mentioned anonymous Old Believers and, in general, did not find it necessary to remain within the narrow confines of this little marginal world of the Russian school in Paris. She began taking lessons with a well-known French painter who worked on Church commissions, surrounded by dozens of monumental works and paintings of religious subjects. Maurice Denis (1870 - 1943), though hardly an iconographer in the Orthodox sense of the term, was an artist of eminent merit in the Catholic artistic school, who succeeded in reviving and breathing new life into and raising to another level Catholic religious imagery, the boring and sugary style of which was very close to that of the craft-Academic Russian icons of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In Denis’s paintings and panels one senses a genuine mystical flame, a hymn to the grace of the Creation, a warm appreciation of the contemplation of this beautiful, sun-drenched world where there are so many flowers, chaste girls and chubby-cheeked babies singing the Lord's praises in joyful accord. Although formally part of the art nouveau movement, Denis is undoubtedly head and shoulders above the general level of this spiritually destructive individualist and mannerist world. Denis was one of the very small number of those who succeeded in moving behind the decadent and poisoned spirit of their time to affirm beauty, life and goodness in the apparently typical shapes of Art nouveau.

Even so, what was excellent as decoration for Catholic churches, did not englobe the full Orthodox plenitude of the knowledge of God. One senses a certain lack in Denis's tender, gentle figures in their bourgeois, paradisiacal glasshouses. They do not belong beside the figures of orthodox iconography who regard the spectator in the eye with wisdom, virility, concentration, virtue and love. Reitlinger felt this too, and after three years she left Denis, and with him perhaps the only school imbued with a Christian spirit and a high level of professionalism existing in the Paris of her day, disappointed and unhappy. She began her own research. This research was beyond the strength of a young girl who was neither particularly gifted nor sufficiently trained.

It is possible that if Reitlinger had had the humility to achieve first of all a certain level of professionalism under Denis’s direction and, then purifying, ennobling and correcting her style, had made it suitable for expression the truth of Orthodoxy, she would have become a decent iconographer, though not in the Byzantine style. This, unfortunately, was not to be. The cause almost certainly lay in this militant absolutization of the Byzantine style, this suffocating nostalgic atmosphere which pushed the iconographers of the first emigration to create a tradition out of nothing. And really out of nothing: Reitlinger’s only exposure to the traditional Russian icon was at the exhibition of the Soviet museums of ancient Russian art which was held in Munich in 1928. In order to look once at works accessible then to any Soviet citizen, she was forced to cross half of Europe and sacrifice a sum of money well beyond her poor resources. But to see such works, and even to sketch them in an exhibition hall, is not the same as mastering the tradition. The impressions she left with were enough to disappoint her of the lessons of both the Old Believers and Maurice Denis, but not to master the style of the medieval iconographers.

Reitlinger’s subsequent - and long - creative biography shows her flitting about in a search for what she herself called the «creative icon». This naive pleonasm did not offend the ears either of Sister Ioanna or her circle. Visibly, they were accustomed to think that the icon, in itself, is not creative at all, and that it is only under the brush of Sister Ioanna that it becomes creative.

Flitting from the stylization to the realistic treatment of shapes, from whitish to dull tones, from sugary sweet rendering to a forced brutality, from canonical iconography to an «iconography» not worthy of this name, Sister Ioanna painted abundantly and in a very varied manner. But never in the tradition, and never in an artistically professional manner. It is amusing to note that the only stable feature of her works is a certain taste for late art nouveau: weak colors, rounded, apathetic silhouettes, like a worn piece of soap. Tired, hesitant lines like the steps of marsh plants, cotton wool faces, bespeaking the influence of Denis or rather a superficial imitation of his style. The master himself did not abuse the tricks of art nouveau and his mature works move beyond the mannerism and typical apathies of this early works, but his pupil remained marked for life by the Paris fashion of the twenties and thirties.

It should be added that Sister Ioanna returned to Russia after World War II with the blessing of Fr Serge Bulgakov. She was in no way involved with the renaissance of the ancient painting tradition in Russia and her «creative» icon found no application in the Church. During the same period her contemporary Mother Juliania - both were born in 1899 - was directing with an experienced hand the restoration work at the Saint Sergius Lavra, founded an icon school, painted icons, wrote icons and books. Sister Ioanna remained on the furthest periphery of Church art. Forced, to earn her keep, to paint scarves in a textile factory, she continued to paint from time to time little icons as presents for her friends. In other words, in the conditions of the true artistic and spiritual tradition of the icon, Reitlinger's creativity received the status it deserved, that of hobby painting.

Let us not ask what role either Uspensky or Krug would have played in the renaissance of the grand Byzantine style if they too had returned to Russia in the 1940s. We prefer to stay with the facts. We do have some indications to go on: among the tens of thousands of icon reproductions published in Russia in recent decades, we find not a single work by these authors. What are published are the icons of Mother Juliania, Father Zinon, Natalia Aldoshina and Sergei Fyodorov and hundreds of other contemporary iconographers, including both real artists and simple artisans. But the creativity of Uspensky and Krug, the two most eminent representatives of the first emigration, are not in demand.

There is no need to mention here the names of those who were less eminent. The artistic level of their production is such that it excludes any possibility of speaking of it as art, of trying to define any stylistic particularities, any tradition ..... One cannot speak of this production, even under the title of traditional craftwork, like one can of popular images or bronze crosses and objets de dévotion.

One cannot seriously talk of a phenomenon of artisanal art work, like brass crosses or matriochkas, without there being at least a hundred or so artisans per village who have painted these matriochkas, in artisan fashion, for fifty years at least. It is important that Ivan paints better matriochkas than Boris and therefore sells them better, and that Boris then tries with all his strength to be better than Ivan, and in that way takes place - albeit in this lowly and brutal art form - the eternal miracle which has ever taken place in true art: the artist’s effort to achieve beauty, and to have this beauty accepted by society, the honest competition of artists searching for perfection, the appearance and development of the school and the tradition, communion and agreement between artists and spectators on what is beautiful and good. Is this what happened with the iconography of the first generation? The answer, alas, is no. As late as the 1960s, Archimandrite Kyprian Pyzhov defined the main difference between Russian iconography and that of the emigration that in Russian icon painting, «as in any other profession, some were better qualified than others, but there was always the training of the craft profession which distinguished any icon painted in Russia from the work practiced abroad. (......) The Russia of the emigration was unable to attain this craft level. Those who imitate the ancient manner without understanding its main merit, its ability to express the spiritual content of the objects painted, and who instead focus attention on «incorrectnesses», that is on the contradictions with a realistic reading, seeing this as the principal and most important feature of this type of work, reinforcing in these «false antiquities» those incorrectnesses which would best have been avoided.«[5]

Summarizing our review of the school and tradition in the iconography of the emigration, one has to conclude that:

a. Even the most eminent, professional or semi-professional iconographers hardly belonged to the traditional icon school. Their creativity, albeit expressing to a certain extent the Orthodox idea of deified man, remained all the same a unique, isolated phenomenon in sacred art, in fact a cul-de-sac. The small number of iconographers of a high level who are working today in Western Europe owe their artistic professionalism to direct contacts with Russia, to the availability nowadays of information on classical medieval icon painting. They certainly do not owe it to the «tradition» of Krug or Reitlinger, not to the «theology» of Uspensky.

b. Outside this group, which in fact was not even a group but a handful of artists working in relative isolation, very different in style and their understanding of the meaning of the icon, in their lifestyles and their destiny, out of range of the real professionals, the iconography of the first generation in Western Europe was not even artisanal artwork, but simply dilettante tinkering. Dilettante, not only at the artistic level, but also at that of the knowledge of canonical iconography and basic theological sentiment. What do we say of people, like Mother (later Saint) Maria Skobtsova ,who use Vroubel's works as models for their icons? Or this new type of icon, by the same painter, of the Mother of God with a little crucifix in her hand figuring a live baby Christ Child?[6] Or of the icon of Sophia, Divine Wisdom, at table with the «New Martyrs of Paris», which is part of the festival of mediocre icon painting, widely disseminated on the internet, following the canonization of the same Mother Maria?[7]

This dilettante and irresponsible approach to the art of the icon has been made possible and has struck even deeper roots since because the theoretical basis justifying it (Leonid Uspensky's «Theology of the Icon» - originally published in French in 1960 under the humbler title «Essay on the Theology of the Icon in the Orthodox Church») was not slow to appear and is seen still today by certain people as unshakeable, even if today it is good tone (in particular if one is not too close to the Church) to speak of the icon in the spirit of certain superstitious agnosticism.

We should also note that the fact that an icon is blessed and thereby becomes a sacred object engenders two phenomena. The first is a taboo against identifying it with a work of art, and therefore removing it from any basic artistic exigencies. The second is the notion that anyone who wants to paint icons can. Together this produces a fateful mixture: zero aesthetic exigency and a cartload of spirituality. Any aesthetic judgment of an icon is considered indecent, whilst dilettante iconography is deemed permissible and even praiseworthy. We have already spoken sufficiently of the indecency of penetrating the spiritual field through the production of cheap little Byzantine images. We shall now go on in the next chapter to look at how the icon lives and acts in the Church, what are the mystical and aesthetic sides to this life, and how the people of God, brought up in the true tradition of Christian art, knows how to distinguish good iconography from bad.

[1] Viktor Vasnetsov, Pisma. Noviya materiali, St Petersburg 2004, pp. 301-303

[2] Quoted in: Irina Yazikova, «Se tvoryu vso novoye» : Ikona v XX veke. La Casa di Matriona, 2002, p. 29

[3] Cited by Irina Yazikova, «Se tvoryu vso novoye» : Ikona v XX veke. La Casa di Matriona, 2002, p. 51

[4] Natalia Bolshakova, Khristianstvo osushestvimo na zemle, Riga, 2006, p. 98

[5] Archimandrite Kyprian Pyzhov K poznaniyu pravoslavnoye ikonopisi «Pravoslavnaya Zhizn», Jourdainville, 1966, no. 1, pp. 8-13;

[6] Irina Yazikova, «Se tvoryu vso novoye» : Ikona v XX veke. La Casa di Matriona, 2002, p. 32

[7] http://www.flickr.com/photos/jimforest/sets/164907/