THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 12 - On the veneration of icons...

Оригинал взят у mmekourdukova в THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 12 - On the veneration of icons...

On the veneration of icons and the assessment of their artistic level

In this chapter we discuss a matter that lies outside the field of art history, but concerns rather the life and use of the icon within the Church, the people of God.

The fundamental issues related to the veneration of icons were settled and regulated by the Church already more than a thousand years ago by the Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II (787) following the iconoclast controversies. This is not the place to rehearse the history of this process, even briefly, or to quote the Acts of this council. All this is very well known and needs explaining only to those far from the Church.

What we want to examine here is something very different, the difficult question of what relationship exists, if any, between the artistic level of the icon and the special role the Church destines for icons. Some works indeed exhibit such artistic poverty that the question arises of whether to accept them for public veneration, or if already placed for veneration, of maintaining them there. In general, the Church behaves in such situations in the same way as with a member whose behaviour no longer matches its heavenly ideal, with both tolerance and strictness, forgiving the weak and sinful, but never allowing sin to become the standard or, a fortiori, a virtue.

Icons of poor quality have always existed in the Church, as has the desire to replace them, as soon as possible, by other, better painted ones. Formerly old icons, when they had become too knocked about or blackened, or were of obviously inferior quality (in medieval Russian nyepodobnye = both «not resembling» and «unworthy»), were destroyed. This destruction was of course carried out with the utmost respect, burning them or sinking them into a river or lake, but in any case they were well and truly destroyed! This procedure expressed not only the respect due to them as sacred objects, mediators between God and man, but also the awareness of the fragile impermanence of these manufactured objects that could no longer fulfil their liturgical function or testify to God's beauty.

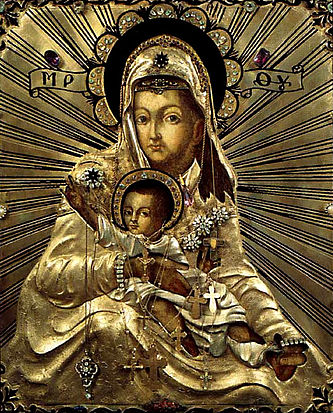

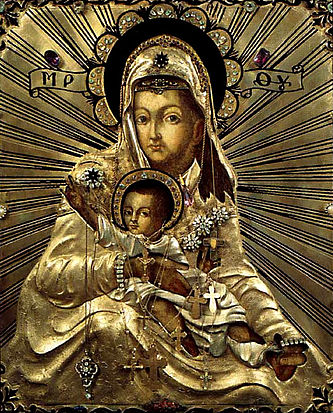

This left the Church with the problem of miracle-working icons. Their destruction is not an option because their mystical function totally dwarfs their aesthetic one: the Holy Spirit blows where He wills, making holy and precious an icon, the pictorial quality of which can be excellent, average or downright disastrous if coming from the hands of a poor craftsman. This icon, having became mystical object, was then surrounded by a special reverence. Even so the Church was not content merely with the sacral aspect, forgetting any aesthetic requirement, and instead took special care of the beauty of these icons. Stepan Ryabushinski, in his notes on the restoration of the icons published in 1928[1] gives us information on the cleaning and restoration of highly venerated icons in the Middle Ages, at a time when the restoration of ancient icons, as we understand it today, did not yet exist. For example, it was not uncommon for an icon (not miraculous) to be completely covered with successive repaintings, and there are even cases where the board was simply replastered and newly painted. But most of the time much revered icons are protected by an oklad (metal cover), the precious metals, the fine decorative work, the shiny gems and pearls of which serve to conceal the blackened beauty, destroyed by merciless time, which has ceased to be beautiful and at times never was. Which is why these miraculous icons are surrounded by icon lights, votive gifts, carved and gilded glazed cases, embroidered cloths, all this accumulation that is so common in Orthodox culture, with no other purpose than to mitigate and soften the objective ugliness of the image itself. The person venerating the icon could, to a certain measure, be consoled for the absence of the beauty of the deified man represented in a perfect work of art by observing the finesse of the decorative work, and admiring the quality and sustainability of the precious materials used.

In this context we note that icons produced during the period of decadence, when icon production was left in the hands of lesser quality artisans, clearly demonstrate this enthusiasm for a substitutionary ornamentation that ends us becoming a goal in itself, and relegating to the background the beauty of the iconic image itself. It is perhaps precisely this substitution that explains the very rapid decisive invasion of the Western style in Russian painting. Even if the Western works imitated in the seventeenth century by Russian icon painters were still far from true spirituality, we must admit that they were closer to the image of deified man than the expressionless figures of the traditional Russian icons of the same period, drowned in ornaments, cloudlets, flower garlands and the refined folds of their clothing. Paradoxical as it may seem, it is the penetration into Russia of the «Italian» style that brought the rebirth of this capital ontological requirement: that the icon should reflect the image of the psychological and spiritual wholeness of deified man, without becoming a richly decorated idol. Let us remember that the adoption and acculturation of the «Italian» style took place as much for religious as for aesthetic reasons. We note that several Italian madonnas introduced into Russia by foreigners were recognized as miraculous, accepted as such by the Church which had recognized the work of the Holy Spirit in them and included in the Orthodox calendar. This is the origin, confirmed by documents, of certain types of icons of the Mother of God, like that of the Three Joys, the Kozeltchanskaya, that of Seraphim of Diviyevo, of Kaluga and a whole series of others.[2]

The wise distinction made by the Church between the spiritual and aesthetic functions of the icon is also evident in the historical practice of copying miraculous icons. These copied versions, also called spiski [3], are not the result of mechanical copying. The only requirement was to follow the iconographic canon of the model in terms of the posture of the characters, their clothes, and (for men) their hair and beards. The rest, to be done «according to measure and beauty» as it says in medieval contracts, was left to the responsibility of the artist. Ideally, the spissok should surpass the original in beauty, and it was not rare that this ideal was reached. Let us mention in this context that the copying of Byzantine models in the Academic style and, the other way round, the copying of Academic models by craft-painters working in the Byzantine style, were totally normal phenomena of Russian culture.

In her early days in the Church, the author sometimes felt a sense of unease, of hesitation and dissatisfaction with some highly venerated icons that did not shine at all for their artistic beauty. «This is the way to behave,» she said, looking at the heavy and ungrateful faces that appeared in the cutouts of the okladi. «There must be something here, since everyone worships this icon; I too must venerate it.» And so she crossed herself and pressed her lips to the oklad or the protective glass, but still with doubts in her mind and a sense of dissatisfaction. It was only later, through the experience of prayer and taking part in the services that she was able to overcome these feelings. The acquisition of a deeper knowledge of Christian art, especially by learning icon painting, and the gradual appearance in Russian churches of beautiful contemporary icons, enabled the author to establish a more luminous relationship with the venerated icons that had previous offended her aesthetic sensitivities. She stopped forcing herself, trying in vain to convince her heart that the ugly can be beautiful. In the Church we can, indeed must, learn to distinguish beauty from ugliness, and their different degrees. We can, and indeed must, love beauty and shun ugliness, but also pardoning ugliness when we cannot do otherwise.

It is sometimes easier to forgive ugliness, and even do so with all one's heart, in the case of an ancient icon whose naive author has clearly been unable to undertake serious studies, but on the other hand has put into his work all his good will of a humble craftsman, all his meticulous care, and all his honest search for beauty and perfection. But forgiveness is less easy, and is granted only with a certain bitterness, and even a certain shame, when one senses in a painter a too blatant vanity, and the cold and audacious pretension to be in phase with the Holy Spirit. It must be said that among widely venerated icons of poor quality, the majority belong to the first category, that of «naive good will.» One senses such a thirst for celestial harmony, such anguish of the painter brought face-to-face with his shortcomings, so much effort, even if clumsy, to achieve perfection, that the icon appears to open up the path to beauty, and to harmony.

But it is another matter when the ugliness falls into the second category ('pretentious vanity'). In the famous conflict of styles of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, we must emphasize the important role played by this intuitive preference for ugliness due to «naive good will» over to that due to «pretentious vanity». The uninspired craftsmanship of standard Byzantine icons was actually much less spirituality-bearing than the first shy and awkward steps toward mastery of the Italian manner. The Church accepted and blessed these first attempts, this honest search for life and beauty, and in this way found itself holding a huge number of beautiful icons in this new style. This enabled it to harvest many artists' souls which also expressed the soul of the people, artists who found in the Church the space which allowed them to develop their talent as well as the highest standards. They no longer needed to look outside of the Church. It must also be said in passing that the Academic style sometimes also begat its own artisanal current, its own ugly second-class products. But the Church is not deceived by the work of «Academic artisans» and does not take this for the pinnacle of artistic creation any more than it did the work of «Byzantine artisans».

The Church venerates, in an icon that has been blessed and proposed for prayer, the hoped-for, invisible and mysterious presence of the Spirit. In icon painting, the Church values, today as in previous centuries, the visible expression of the Spirit, which is always present in her. It is this visible expression through Beauty and Truth that defines specificity of the icon relative to other sacred objects. The Orthodox idea of the possibility and reality of the Incarnation of God in man is expressed by the fact that the Church venerates in the icon the visible manifestation of the Spirit, in the same way that she is open to the possible presence of the Spirit breathing mysteriously on the person praying in front of the icon.

Sacred objects as mediators and accumulators spiritual forces exist in all religions, and even in paganism, with its talismans, apotropaic objects, and idols of every kind. Sometimes these are non-figurative objects, and at other times works of art executed with great taste. Yet the invisible spirit present in these objects is not the Holy Spirit. The demonic nature of this spirit is sometimes expressed very directly in the images of the pagan sacred art. In Christianity, we also find sacred objects, of two types. The objects of the first kind, such as the cross, the sacred vessels or the Gospel, are sacred because, according to the promise given to the Church, the Holy Spirit rests on them. Those of the second kind, sacred images, are sacred because they reveal and proclaim the invisible world to the Church and to the entire universe. The very existence of the icons is justified only because they have a mission to witness to and proclaim the Incarnation.

The heresy of iconoclasm emerged, inter alia, as a reaction to a mis-use of icons. Overzealous admirers sewed small icon-talismans in their clothes, summonsed icons to appear as witnesses in front of a court or a notary, or added into the chalice paint scraped from icons to increase the holiness of the Blood of Christ. In other words, for them icons functioned as no more than spiritual energy accumulators, in so doing triggering accusations of idolatry by the iconoclasts. The restoration of the veneration of icons, condemning idolatry in general and the idolatry of icons in particular, has confirmed their role of «incarnation witnesses», which is the specific function of icons, as is indeed, more widely, that of Christianity.

Two equally miraculous and mysterious spiritual phenomena are involved in the use of icons in the Church: first, the touching of the Spirit coming down on any material object, second the fact that a work created by the Spirit, through the hand of an artist, witnesses to God incarnate in a clear and indisputable manner.

Here is now a story that perfectly expresses the distinction between the aesthetic and mystical sides in the icon, and the distinction between the invisible descent of the Spirit, regardless of our imperfection, and the transmission of the same Spirit in the form of sacred art: in the early 1990s, the author was invited to the presentation of the work of the students of an iconography school in Saint Petersburg. It was an amateur school: the students were of various ages and of very uneven levels of artistic training. They undertook, with the group of teachers and some guest iconographers, the customary exhibition tour of their work (exercises, studies, copies), listening to the observations and evaluations of their elders. The work of one student, a man of around fifty, exceeded the general level, with its particularly clean finish, very accurate drawing, and a very deep understanding of tradition. They were much appreciated them and a guest examiner asked the author, all pink with pleasure, if he had received training in the fine arts. The «first in the class» was a graduate graphic designer who had in fact worked for several years in the propaganda services. The examiner then asked him if he had ever painted icons before beginning his regular iconography studies. With obvious embarrassment, the brilliant student said yes. «For the Church? », the examiner continued. «Yes, for the Church,» he replied without enthusiasm. «And in which churches can we see your work?» the examiner continued, without pity, apparently not noticing that the student would rather disappear through the floor than answer. He mentioned a nearby church, known to all. This elegant eighteenth century church had, ten years earlier, been completely disfigured by huge and ugly icons painted in a very bold, but quite professional way, in this typical Soviet propaganda style, which until their death will arouse nausea in people of the author's generation. All these robust collective farm girls, all these haloed muscular athletes suddenly came to the mind of the audience, who let out a big sigh! The unanimous silence of the fifty people was truly overwhelming. No harsh criticism, no expression of reproach or discontent would better have expressed this feeling mixed with horror and contempt and pity. No one found it necessary to lighten the mood by saying something like «It's okay, now you are painting a lot better! » or «At least now you have started serious studies!» It was clear that the «first in the class» was no longer the same artist as ten years ago, and had made great progress, both spiritually and creatively. He stood there quite embarrassed, and frankly ashamed of his former achievements. Humanly, everyone felt sorry for the artist, although it was hard to forgive the ugliness of its icons, still in place in their church.

A reply by the school’s director, a priest, finally broke the silence, putting his finger on the main reason for the general embarrassment: «We cannot unfortunately do anything about it, since it exudes myrrh.» He was speaking about one of the icons of the Mother of God, of no better quality than the others, which had begun to exude myrrh, making this church a centre of sacred attraction. He knew that even if our excellent student, who had now perfectly mastered the true iconographic tradition, were to repaint for free all the icons of this church to atone for the sins of his youth, or if the rector of the church decided to commission replacement icons from the best artists in the country, the icon in question would still remain in place, continuing to disturb the parishioners with its unbearable vulgarity. He, like the rest of the audience, knew how difficult it is to forgive this ugliness «of the second type» due to the stupid, vain pride of a badly-trained painter.

But there is still a third and final type of ugliness, with which the author of this book was confronted for the first time when discovering the contemporary iconography of Western Europe. What is this ugliness? Here, the artist does not even aim to achieve convincing and beautiful images. He has read in a popular book, or has heard his teacher say, that an icon has no need to be beautiful or bear a likeness to creation. Full of good will, our apprentice has accepted this vision of things. All his efforts, fairly sustained it must be said, aim in a different direction: the imitation, in line with the rantings he has endorsed, of one or another style of the past. In this way he attempts to paint in a style that is totally alien to him, which is not connected to any reality of his life, whether aesthetic or psychological or spiritual. The author has to admit that she has not yet learned to forgive that kind of ugliness!

http://www.eileencunis.com/icons.html

https://sites.google.com/site/annadumoulin/theiconographer'smanuel

https://abbamoses.wordpress.com/page/21/

http://www.sanmiguelicons.com/blog/wordpress/tag/egg-tempera-technique/

One can perhaps forgive someone who can not do better. But in this third case, yes, it is quite possible to do better. If these constructions foreign to Beauty and Truth that our self-proclaimed iconographer elaborates on his board are foreign even to him, then yes we can do better. We must do better. It is blasphemous to undertake to produce an icon without aiming, from the depths of one's heart, for the supreme reality and objective Beauty: for there is no other Beauty.

Depending on the case, one can pardon an icon-painter’s professional shortcomings, one can perhaps even possibly forgive his superficial, mediocre and vulgar understanding of divine Beauty. But it is absolutely impossible to forgive anyone who voluntarily turns his back on Beauty and Truth.

The Church cannot accept icons where the painter's hand does not pursue Beauty and Truth, but simply uses certain elements of a poorly understood Byzantine style; even if this icon ends up being blessed by some ignorant or irresponsible clergyman. There is no question of accepting it the apostasy that makes a «virtue out of necessity». First of all there is no necessity here, but rather sloppiness and lack of education, a lie and loosening of the reins of the interior life hidden behind a meaningless mental masturbation. And it not the fact of blessing such images or hanging them in a church that will change anything. Consecration is not a magic act by which which judicious abracadabra automatically converts any daubing into an icon. Collector V.P. Ryabushinsky, who was also an expert and member of the society Icône[4], ostentatiously refused to venerate certain icons in various Orthodox churches in Paris. He explained this saying that in the same way that the Eucharist, the greatest of mysteries, can bring, not salvation, but «judgement and condemnation», similarly the veneration of unworthy icons can also be regarded not as a liturgical act, but as blasphemy.[5]

The Russians are always surprised at the total indifference that surrounds in Western Europe the work of contemporary iconographers, while in Russia the interest in contemporary icons continues to grow. Indeed, Orthodox parishes in Western Europe order their icons in Russia or Greece, even though there are plenty of icon painters working in their own countries. Contemporary icons in Europe are present only in charity exhibitions, and not at all on the art gallery circuit: the public could not care, the commercial interest is zero. Neither professional artists nor young people visit them. People never linger long in front of the exhibited icons, and never return to see the most popular. Nobody makes sketches of details or interesting compositions, as is frequently seen at icon exhibitions in Russia. Here in Europe, icon exhibitions are attended by only a small circle of insiders (the organizers, the painters, and their friends and acquaintances). They come, not to contemplate divine beauty, but for the pleasure of being together, to listen once again a conference on King Abgar or reverse perspective, and to support their creative or spiritual ambitions. A neophyte who stumbles into such meetings will experience a certain malaise, and may even be seriously troubled. The impressionable or those with weak personalities will feel disoriented, but the psychologically more stable will surely ask questions about the mental health of participants. On coming to live in Western Europe, the author was initially ashamed to admit her profession: it is hard to take when intelligent, friendly people, who have just gently shaken your hand, suddenly raise and eyebrow and pinch their lips on learning that you are iconographer. In their eyes, iconographers can only be charlatans or mentally unstable. One is inevitably reminded of Gogol's words in his Selected Letters to Friends: «They say that our Church is dead. This is false, because our Church is life itself; but we quite correctly arrived at this counter-truth by proper deduction. It is we who are the corpses, not our church, and it's because of us that the Church in turn is treated as a corpose.»

Iconography is Beauty, Truth and Life. If an impartial and unprejudiced onlooker, using «proper deduction», does not perceive the Beauty, Truth and Life of an «artistic experience», this is simply because it is not an icon. To paraphrase Gogol, no more than a corpse.

But how does this corpse survive, and what does it feed on? And how does it still manage to pass itself off as Truth and Life? And how can this this corpse be brought back to life? The resuscitation process is complex, and deserves a separate chapter, as it will require us to move away, not only from the relationship between the veneration of icons and their aesthetic evaluation, but also from the walls of the Church.

[1] S. Ryabushinsky, Заметки о реставрации икон. В кн. Богословие образа. Икона и иконописцы, under the direction of A.N. Strijov, Moscow , 2002, pp. 426-428.

[2] A. A. Voronov, E.G. Sokolova, Чудотворные иконы Богоматери, Moscou, 1993.

[3] Spiski, name meaning copy (written or painted), from the the verb pissat', which means both to paint and to write. This double use of the term in Russian explains the widespread error of people speaking of writing icons instead of painting them.

[4] Association of icon)lovers and connoisseurs of the first Russian emigration in Paris, which existed until the 1950s.

[5] V.P. Ryabushinsky, Литургическое значение священного искусства, dans Le Messager (A.C.E.R.) no. 35, Paris-New York.

On the veneration of icons and the assessment of their artistic level

In this chapter we discuss a matter that lies outside the field of art history, but concerns rather the life and use of the icon within the Church, the people of God.

The fundamental issues related to the veneration of icons were settled and regulated by the Church already more than a thousand years ago by the Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II (787) following the iconoclast controversies. This is not the place to rehearse the history of this process, even briefly, or to quote the Acts of this council. All this is very well known and needs explaining only to those far from the Church.

What we want to examine here is something very different, the difficult question of what relationship exists, if any, between the artistic level of the icon and the special role the Church destines for icons. Some works indeed exhibit such artistic poverty that the question arises of whether to accept them for public veneration, or if already placed for veneration, of maintaining them there. In general, the Church behaves in such situations in the same way as with a member whose behaviour no longer matches its heavenly ideal, with both tolerance and strictness, forgiving the weak and sinful, but never allowing sin to become the standard or, a fortiori, a virtue.

Icons of poor quality have always existed in the Church, as has the desire to replace them, as soon as possible, by other, better painted ones. Formerly old icons, when they had become too knocked about or blackened, or were of obviously inferior quality (in medieval Russian nyepodobnye = both «not resembling» and «unworthy»), were destroyed. This destruction was of course carried out with the utmost respect, burning them or sinking them into a river or lake, but in any case they were well and truly destroyed! This procedure expressed not only the respect due to them as sacred objects, mediators between God and man, but also the awareness of the fragile impermanence of these manufactured objects that could no longer fulfil their liturgical function or testify to God's beauty.

This left the Church with the problem of miracle-working icons. Their destruction is not an option because their mystical function totally dwarfs their aesthetic one: the Holy Spirit blows where He wills, making holy and precious an icon, the pictorial quality of which can be excellent, average or downright disastrous if coming from the hands of a poor craftsman. This icon, having became mystical object, was then surrounded by a special reverence. Even so the Church was not content merely with the sacral aspect, forgetting any aesthetic requirement, and instead took special care of the beauty of these icons. Stepan Ryabushinski, in his notes on the restoration of the icons published in 1928[1] gives us information on the cleaning and restoration of highly venerated icons in the Middle Ages, at a time when the restoration of ancient icons, as we understand it today, did not yet exist. For example, it was not uncommon for an icon (not miraculous) to be completely covered with successive repaintings, and there are even cases where the board was simply replastered and newly painted. But most of the time much revered icons are protected by an oklad (metal cover), the precious metals, the fine decorative work, the shiny gems and pearls of which serve to conceal the blackened beauty, destroyed by merciless time, which has ceased to be beautiful and at times never was. Which is why these miraculous icons are surrounded by icon lights, votive gifts, carved and gilded glazed cases, embroidered cloths, all this accumulation that is so common in Orthodox culture, with no other purpose than to mitigate and soften the objective ugliness of the image itself. The person venerating the icon could, to a certain measure, be consoled for the absence of the beauty of the deified man represented in a perfect work of art by observing the finesse of the decorative work, and admiring the quality and sustainability of the precious materials used.

In this context we note that icons produced during the period of decadence, when icon production was left in the hands of lesser quality artisans, clearly demonstrate this enthusiasm for a substitutionary ornamentation that ends us becoming a goal in itself, and relegating to the background the beauty of the iconic image itself. It is perhaps precisely this substitution that explains the very rapid decisive invasion of the Western style in Russian painting. Even if the Western works imitated in the seventeenth century by Russian icon painters were still far from true spirituality, we must admit that they were closer to the image of deified man than the expressionless figures of the traditional Russian icons of the same period, drowned in ornaments, cloudlets, flower garlands and the refined folds of their clothing. Paradoxical as it may seem, it is the penetration into Russia of the «Italian» style that brought the rebirth of this capital ontological requirement: that the icon should reflect the image of the psychological and spiritual wholeness of deified man, without becoming a richly decorated idol. Let us remember that the adoption and acculturation of the «Italian» style took place as much for religious as for aesthetic reasons. We note that several Italian madonnas introduced into Russia by foreigners were recognized as miraculous, accepted as such by the Church which had recognized the work of the Holy Spirit in them and included in the Orthodox calendar. This is the origin, confirmed by documents, of certain types of icons of the Mother of God, like that of the Three Joys, the Kozeltchanskaya, that of Seraphim of Diviyevo, of Kaluga and a whole series of others.[2]

The wise distinction made by the Church between the spiritual and aesthetic functions of the icon is also evident in the historical practice of copying miraculous icons. These copied versions, also called spiski [3], are not the result of mechanical copying. The only requirement was to follow the iconographic canon of the model in terms of the posture of the characters, their clothes, and (for men) their hair and beards. The rest, to be done «according to measure and beauty» as it says in medieval contracts, was left to the responsibility of the artist. Ideally, the spissok should surpass the original in beauty, and it was not rare that this ideal was reached. Let us mention in this context that the copying of Byzantine models in the Academic style and, the other way round, the copying of Academic models by craft-painters working in the Byzantine style, were totally normal phenomena of Russian culture.

In her early days in the Church, the author sometimes felt a sense of unease, of hesitation and dissatisfaction with some highly venerated icons that did not shine at all for their artistic beauty. «This is the way to behave,» she said, looking at the heavy and ungrateful faces that appeared in the cutouts of the okladi. «There must be something here, since everyone worships this icon; I too must venerate it.» And so she crossed herself and pressed her lips to the oklad or the protective glass, but still with doubts in her mind and a sense of dissatisfaction. It was only later, through the experience of prayer and taking part in the services that she was able to overcome these feelings. The acquisition of a deeper knowledge of Christian art, especially by learning icon painting, and the gradual appearance in Russian churches of beautiful contemporary icons, enabled the author to establish a more luminous relationship with the venerated icons that had previous offended her aesthetic sensitivities. She stopped forcing herself, trying in vain to convince her heart that the ugly can be beautiful. In the Church we can, indeed must, learn to distinguish beauty from ugliness, and their different degrees. We can, and indeed must, love beauty and shun ugliness, but also pardoning ugliness when we cannot do otherwise.

It is sometimes easier to forgive ugliness, and even do so with all one's heart, in the case of an ancient icon whose naive author has clearly been unable to undertake serious studies, but on the other hand has put into his work all his good will of a humble craftsman, all his meticulous care, and all his honest search for beauty and perfection. But forgiveness is less easy, and is granted only with a certain bitterness, and even a certain shame, when one senses in a painter a too blatant vanity, and the cold and audacious pretension to be in phase with the Holy Spirit. It must be said that among widely venerated icons of poor quality, the majority belong to the first category, that of «naive good will.» One senses such a thirst for celestial harmony, such anguish of the painter brought face-to-face with his shortcomings, so much effort, even if clumsy, to achieve perfection, that the icon appears to open up the path to beauty, and to harmony.

But it is another matter when the ugliness falls into the second category ('pretentious vanity'). In the famous conflict of styles of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, we must emphasize the important role played by this intuitive preference for ugliness due to «naive good will» over to that due to «pretentious vanity». The uninspired craftsmanship of standard Byzantine icons was actually much less spirituality-bearing than the first shy and awkward steps toward mastery of the Italian manner. The Church accepted and blessed these first attempts, this honest search for life and beauty, and in this way found itself holding a huge number of beautiful icons in this new style. This enabled it to harvest many artists' souls which also expressed the soul of the people, artists who found in the Church the space which allowed them to develop their talent as well as the highest standards. They no longer needed to look outside of the Church. It must also be said in passing that the Academic style sometimes also begat its own artisanal current, its own ugly second-class products. But the Church is not deceived by the work of «Academic artisans» and does not take this for the pinnacle of artistic creation any more than it did the work of «Byzantine artisans».

The Church venerates, in an icon that has been blessed and proposed for prayer, the hoped-for, invisible and mysterious presence of the Spirit. In icon painting, the Church values, today as in previous centuries, the visible expression of the Spirit, which is always present in her. It is this visible expression through Beauty and Truth that defines specificity of the icon relative to other sacred objects. The Orthodox idea of the possibility and reality of the Incarnation of God in man is expressed by the fact that the Church venerates in the icon the visible manifestation of the Spirit, in the same way that she is open to the possible presence of the Spirit breathing mysteriously on the person praying in front of the icon.

Sacred objects as mediators and accumulators spiritual forces exist in all religions, and even in paganism, with its talismans, apotropaic objects, and idols of every kind. Sometimes these are non-figurative objects, and at other times works of art executed with great taste. Yet the invisible spirit present in these objects is not the Holy Spirit. The demonic nature of this spirit is sometimes expressed very directly in the images of the pagan sacred art. In Christianity, we also find sacred objects, of two types. The objects of the first kind, such as the cross, the sacred vessels or the Gospel, are sacred because, according to the promise given to the Church, the Holy Spirit rests on them. Those of the second kind, sacred images, are sacred because they reveal and proclaim the invisible world to the Church and to the entire universe. The very existence of the icons is justified only because they have a mission to witness to and proclaim the Incarnation.

The heresy of iconoclasm emerged, inter alia, as a reaction to a mis-use of icons. Overzealous admirers sewed small icon-talismans in their clothes, summonsed icons to appear as witnesses in front of a court or a notary, or added into the chalice paint scraped from icons to increase the holiness of the Blood of Christ. In other words, for them icons functioned as no more than spiritual energy accumulators, in so doing triggering accusations of idolatry by the iconoclasts. The restoration of the veneration of icons, condemning idolatry in general and the idolatry of icons in particular, has confirmed their role of «incarnation witnesses», which is the specific function of icons, as is indeed, more widely, that of Christianity.

Two equally miraculous and mysterious spiritual phenomena are involved in the use of icons in the Church: first, the touching of the Spirit coming down on any material object, second the fact that a work created by the Spirit, through the hand of an artist, witnesses to God incarnate in a clear and indisputable manner.

Here is now a story that perfectly expresses the distinction between the aesthetic and mystical sides in the icon, and the distinction between the invisible descent of the Spirit, regardless of our imperfection, and the transmission of the same Spirit in the form of sacred art: in the early 1990s, the author was invited to the presentation of the work of the students of an iconography school in Saint Petersburg. It was an amateur school: the students were of various ages and of very uneven levels of artistic training. They undertook, with the group of teachers and some guest iconographers, the customary exhibition tour of their work (exercises, studies, copies), listening to the observations and evaluations of their elders. The work of one student, a man of around fifty, exceeded the general level, with its particularly clean finish, very accurate drawing, and a very deep understanding of tradition. They were much appreciated them and a guest examiner asked the author, all pink with pleasure, if he had received training in the fine arts. The «first in the class» was a graduate graphic designer who had in fact worked for several years in the propaganda services. The examiner then asked him if he had ever painted icons before beginning his regular iconography studies. With obvious embarrassment, the brilliant student said yes. «For the Church? », the examiner continued. «Yes, for the Church,» he replied without enthusiasm. «And in which churches can we see your work?» the examiner continued, without pity, apparently not noticing that the student would rather disappear through the floor than answer. He mentioned a nearby church, known to all. This elegant eighteenth century church had, ten years earlier, been completely disfigured by huge and ugly icons painted in a very bold, but quite professional way, in this typical Soviet propaganda style, which until their death will arouse nausea in people of the author's generation. All these robust collective farm girls, all these haloed muscular athletes suddenly came to the mind of the audience, who let out a big sigh! The unanimous silence of the fifty people was truly overwhelming. No harsh criticism, no expression of reproach or discontent would better have expressed this feeling mixed with horror and contempt and pity. No one found it necessary to lighten the mood by saying something like «It's okay, now you are painting a lot better! » or «At least now you have started serious studies!» It was clear that the «first in the class» was no longer the same artist as ten years ago, and had made great progress, both spiritually and creatively. He stood there quite embarrassed, and frankly ashamed of his former achievements. Humanly, everyone felt sorry for the artist, although it was hard to forgive the ugliness of its icons, still in place in their church.

A reply by the school’s director, a priest, finally broke the silence, putting his finger on the main reason for the general embarrassment: «We cannot unfortunately do anything about it, since it exudes myrrh.» He was speaking about one of the icons of the Mother of God, of no better quality than the others, which had begun to exude myrrh, making this church a centre of sacred attraction. He knew that even if our excellent student, who had now perfectly mastered the true iconographic tradition, were to repaint for free all the icons of this church to atone for the sins of his youth, or if the rector of the church decided to commission replacement icons from the best artists in the country, the icon in question would still remain in place, continuing to disturb the parishioners with its unbearable vulgarity. He, like the rest of the audience, knew how difficult it is to forgive this ugliness «of the second type» due to the stupid, vain pride of a badly-trained painter.

But there is still a third and final type of ugliness, with which the author of this book was confronted for the first time when discovering the contemporary iconography of Western Europe. What is this ugliness? Here, the artist does not even aim to achieve convincing and beautiful images. He has read in a popular book, or has heard his teacher say, that an icon has no need to be beautiful or bear a likeness to creation. Full of good will, our apprentice has accepted this vision of things. All his efforts, fairly sustained it must be said, aim in a different direction: the imitation, in line with the rantings he has endorsed, of one or another style of the past. In this way he attempts to paint in a style that is totally alien to him, which is not connected to any reality of his life, whether aesthetic or psychological or spiritual. The author has to admit that she has not yet learned to forgive that kind of ugliness!

http://www.eileencunis.com/icons.html

https://sites.google.com/site/annadumoulin/theiconographer'smanuel

https://abbamoses.wordpress.com/page/21/

http://www.sanmiguelicons.com/blog/wordpress/tag/egg-tempera-technique/

One can perhaps forgive someone who can not do better. But in this third case, yes, it is quite possible to do better. If these constructions foreign to Beauty and Truth that our self-proclaimed iconographer elaborates on his board are foreign even to him, then yes we can do better. We must do better. It is blasphemous to undertake to produce an icon without aiming, from the depths of one's heart, for the supreme reality and objective Beauty: for there is no other Beauty.

Depending on the case, one can pardon an icon-painter’s professional shortcomings, one can perhaps even possibly forgive his superficial, mediocre and vulgar understanding of divine Beauty. But it is absolutely impossible to forgive anyone who voluntarily turns his back on Beauty and Truth.

The Church cannot accept icons where the painter's hand does not pursue Beauty and Truth, but simply uses certain elements of a poorly understood Byzantine style; even if this icon ends up being blessed by some ignorant or irresponsible clergyman. There is no question of accepting it the apostasy that makes a «virtue out of necessity». First of all there is no necessity here, but rather sloppiness and lack of education, a lie and loosening of the reins of the interior life hidden behind a meaningless mental masturbation. And it not the fact of blessing such images or hanging them in a church that will change anything. Consecration is not a magic act by which which judicious abracadabra automatically converts any daubing into an icon. Collector V.P. Ryabushinsky, who was also an expert and member of the society Icône[4], ostentatiously refused to venerate certain icons in various Orthodox churches in Paris. He explained this saying that in the same way that the Eucharist, the greatest of mysteries, can bring, not salvation, but «judgement and condemnation», similarly the veneration of unworthy icons can also be regarded not as a liturgical act, but as blasphemy.[5]

The Russians are always surprised at the total indifference that surrounds in Western Europe the work of contemporary iconographers, while in Russia the interest in contemporary icons continues to grow. Indeed, Orthodox parishes in Western Europe order their icons in Russia or Greece, even though there are plenty of icon painters working in their own countries. Contemporary icons in Europe are present only in charity exhibitions, and not at all on the art gallery circuit: the public could not care, the commercial interest is zero. Neither professional artists nor young people visit them. People never linger long in front of the exhibited icons, and never return to see the most popular. Nobody makes sketches of details or interesting compositions, as is frequently seen at icon exhibitions in Russia. Here in Europe, icon exhibitions are attended by only a small circle of insiders (the organizers, the painters, and their friends and acquaintances). They come, not to contemplate divine beauty, but for the pleasure of being together, to listen once again a conference on King Abgar or reverse perspective, and to support their creative or spiritual ambitions. A neophyte who stumbles into such meetings will experience a certain malaise, and may even be seriously troubled. The impressionable or those with weak personalities will feel disoriented, but the psychologically more stable will surely ask questions about the mental health of participants. On coming to live in Western Europe, the author was initially ashamed to admit her profession: it is hard to take when intelligent, friendly people, who have just gently shaken your hand, suddenly raise and eyebrow and pinch their lips on learning that you are iconographer. In their eyes, iconographers can only be charlatans or mentally unstable. One is inevitably reminded of Gogol's words in his Selected Letters to Friends: «They say that our Church is dead. This is false, because our Church is life itself; but we quite correctly arrived at this counter-truth by proper deduction. It is we who are the corpses, not our church, and it's because of us that the Church in turn is treated as a corpose.»

Iconography is Beauty, Truth and Life. If an impartial and unprejudiced onlooker, using «proper deduction», does not perceive the Beauty, Truth and Life of an «artistic experience», this is simply because it is not an icon. To paraphrase Gogol, no more than a corpse.

But how does this corpse survive, and what does it feed on? And how does it still manage to pass itself off as Truth and Life? And how can this this corpse be brought back to life? The resuscitation process is complex, and deserves a separate chapter, as it will require us to move away, not only from the relationship between the veneration of icons and their aesthetic evaluation, but also from the walls of the Church.

[1] S. Ryabushinsky, Заметки о реставрации икон. В кн. Богословие образа. Икона и иконописцы, under the direction of A.N. Strijov, Moscow , 2002, pp. 426-428.

[2] A. A. Voronov, E.G. Sokolova, Чудотворные иконы Богоматери, Moscou, 1993.

[3] Spiski, name meaning copy (written or painted), from the the verb pissat', which means both to paint and to write. This double use of the term in Russian explains the widespread error of people speaking of writing icons instead of painting them.

[4] Association of icon)lovers and connoisseurs of the first Russian emigration in Paris, which existed until the 1950s.

[5] V.P. Ryabushinsky, Литургическое значение священного искусства, dans Le Messager (A.C.E.R.) no. 35, Paris-New York.