THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 13 - The icon: its true place and "theological" fable

Оригинал взят у mmekourdukova в THE ICON: TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 13 - The icon: its true place and «theological» fables

An iconographer expresses him self naturally in images, and the reader will have noticed how many times that author has used stories and anecdote to make her point. We shall do the same in this chapter.

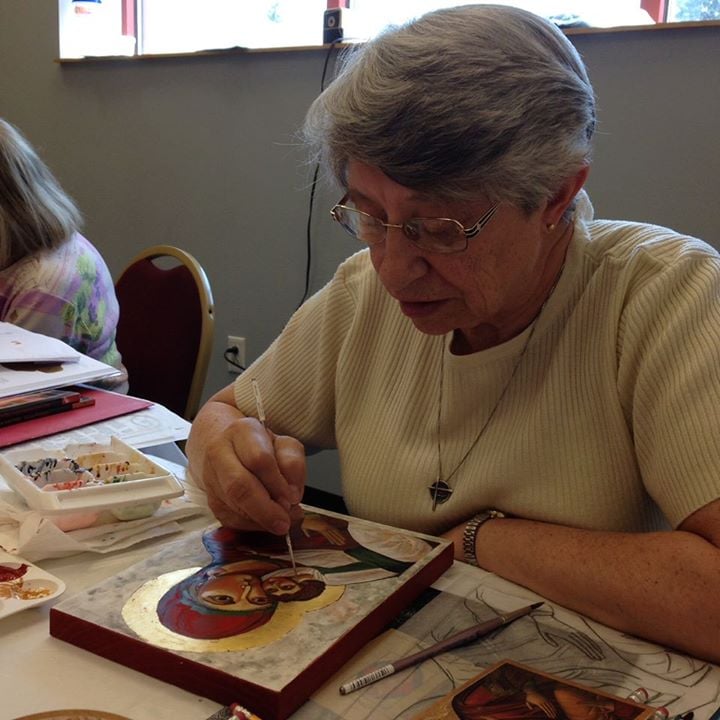

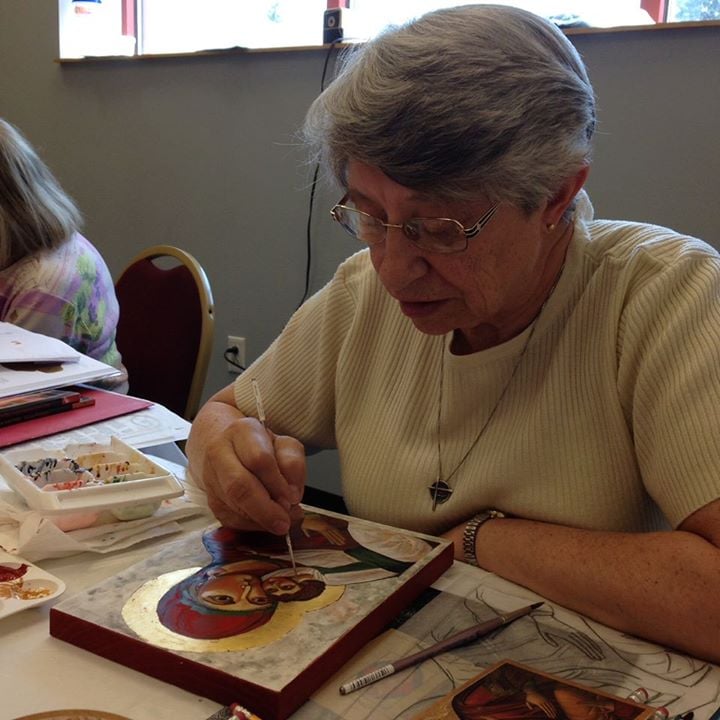

(картинка для привлечения внимания отсюда:

http://www.lsuagcenter.com/~/media/system/e/8/e/5/e8e5a2174f06374448abc7bde9347f0f/jwm_1970jpg.jpg,

как нашла красоту? а погуглила волшебное выражение «icon writing»).

Here is a story that tellingly demonstrates the current status of the icon in Western Europe: first the place of the icon in the Church and in society, and second the vision of the icon - or rather the «theology» thereof - of a handful of «specialists», whose fable-telling provides them with a livelihood and ecclesiastical and social status.

In the 1930s the church of St. John the Warrior in Meudon, a suburb of Paris, was entirely decorated by Sister Ioanna (Julia Reitlinger), a fairly well-known personality of the Russian Orthodox emigration. Endowed with a certain artistic sense, Sister Ioanna had never had any formal training as a painter, rather picking up the crumbs from under the table of Old Believer craftsmen and scenographer Dimitri Stelletsky. She had also followed for a period of three years the advice of the painter Maurice Denis, a fervent, if somewhat bourgeois Catholic, whose decorative panels were very popular at that time. In fact, we find out in her correspondence that Sister Ioanna trusted in particular in her own imagination. Father Sergei Bulgakov, the leading churchman of the Paris emigration, supported her efforts, hoping to obtain, fair from Russia, an iconographer truly worthy of the name. This hope was vain. Only rarely does Sister Ioanna attain in her work an acceptable level of mastery of the icon-painting trade. What we perceive in her is, alas, the longing for spiritual illumination, but not its attainment. Most of her works are characterized by a weak, uncertain line, volumes without modelling and unpleasant yellowish or grayish colors. His characters exhibit at times an almost aggressive nervousness, at others an effete apathy, proof of the difficulty the artist experienced in rendering human traits, whether energetic or tender, in the classical icon-painting styles. With its clumsy drawing and sad colors the decoration of the church of St. John the Warrior too testifies to a poor understanding of the artistic tradition. Only the circumstances of enforced cultural and ecclesiastical isolation in which the Russian émigrés lived can explain that it was tolerated at all.

Our purpose is not so much to dedicate ourselves to the qualitative study of Reitlinger’s works, as to the subsequent fate of her icons and murals, called for no clear reason «frescos» by her followers, even though painted on wood laminate panels. In 1960 the parish was dissolved and the church closed. We cannot attribute this sad fact only to the poverty of the decoration of the church. But neither can we deny that people coming to encounter the Absolute, Almighty and Immortal, and finding themselves in a cultural and spiritual milieu in which everything is approximate, weak and rootless, begin to doubt the Truth or to go looking for it elsewhere. Reitlinger's works do not seem to have fired the heart of the remaining Meudon parishioners, who then abandoned them to their fate. Her works were not entrusted to another parish or transferred to the domestic prayer corners of those who had worshiped and prayed in front of them for nearly thirty years. They were not even sold. The assembly of the faithful, even in this so «Russian Orthodox» corner of France, did not recognize them as carrying any spiritual or artistic or even cultural or historical value. The wider Christian world, orthodox and heterodox, remained equally indifferent. The some twenty years the abandoned church was a refuge for vagrants, with no one, as far as we can tell, ever attempting to remove and sell these Russian icons for a few francs. And this even during the «icons boom» of the 1960s, at the time of renewed interest in the icon around the world, a period of massive export (legal and illegal) of icons from Russia. At that time, Soviet publishers produced a whole series of albums, catalogs and essays on ancient Russian art. Fervent popular writers on the icon, like I. Glazunov and V. Soloukhin, enjoyed a heyday in both Russia and abroad. Andrei Tarkovsky’s famous film Andrei Rublev had just been released. In Paris, these years were marked by the publication and cascading reissues of Uspensky's Theology of the Icon, still today regarded by many as «revealed truth».

In this context of renewal, the lack of interest in the iconographic ensemble of the church of St. John the Warrior, so close to the nerve center of this revived interest, is significant. Whether because everyone had clearly perceived the «quality» of this ensemble, or the Parisian «theology of the icon» was concerned above with its own navel, no matter. The fact is that until the 1980s, the works of Reitlinger, which no one was interested in, remained in the abandoned church, since partially destroyed by fire, maybe caused by the homeless. It was only in 1980 that surviving boards were transported to the castle of Montgeron, where they remained "pending restoration.«[1] The wait lasted more than two decades. Restoration work in Western Europe is very expensive because a restorer, unlike a self-appointed «iconographer», needs to be a professional. No one had been found ready to pay to rescue works which no one had needed even when they were still in fair condition. No volunteer conservator presented himself either to save them, and since Church and art lovers were disinterested, their fate seemed sealed.

The dramatic coup de théâtre took place in 2000. Suddenly, they were once again brought back into the public eye! Not for religious or artistic reasons, but for reasons of «cultural policy». At the time of the restoration of relations between post-perestroika Russia and the Russian emigration, the descendants of the first emigrants, to illustrate the cultural and «orthodox» merits of their predecessors, brought to Russia these once despised works. An expensive exhibition was organized with all the usual trimmings (reception, publications, lectures by experts) after which the boards were donated to the Andrei Rublev museum, placing responsibility for their conservation on its team, all at the expense of the Russian Ministry of Culture.

Has this «gift» had a positive influence in Russia today, on the practice of a better knowledge of God, and better contact with Him? Has this gift substantially increased the presence of divine beauty in a country where the iconographic tradition was never interrupted, a country which boasts a host of world-famous masters, and icon-painting schools of a very high level? The reply is clear. What sense is there in this «cultural investment» and why did the Russians accept the poisoned chalice? Because on the one hand the Russians of France were keen to remind the homeland of their existence and their merits, and on the other hand former Soviets sought to sidle up to the representatives of the legendary first migration. It is clear: worldly and political interests and the race for authority and influence form the basis for these movements that are very far from the true spirit of the Church. We mention here some of the concerns of these influential circles, permeated by this «theology of the icon»:

At the 2005 European Orthodox Congress 2005 in Blankenberge, Belgium, the author had the opportunity to get a deeper insight into the methods used in this kind of courses, by participating in the icon workshop that was proposed as part of this Congress. The presenter spent her entire time slot explaining, line by line, three «special iconographer prayers» of unknown origin. During these two days, the only object that illustrated the speaker's lectures was an unfinished icon of Christ, with a face without eyes, covered with a layer of greenish grime. The second day, the audience had changed: the first day's participants did not return.[2]

All these excesses, and others we talked about in the previous chapter, are impossible when the Church and society demand of the icon both professionalism and Beauty. Wherever this fundamental and ontological requirement is no longer applied to the icon, everything becomes possible: not only the artistic decadence of the icon, but also the elevation of this decadence to a place of tradition and norm; not only the cheating and abuse of trust of those who are looking for spiritual nourishment, but also the devaluation of the icon, and of Christian art in general, in the eyes of the European intelligentsia, both Christian and not. It is sad to see that this catastrophic situation, with the exploitation of the icon to dilettante and selfish ends, finds its basis and justification in the simplistic «theology of the icon» to which the doors were opened with the publication in French in the 1960s of Leonid Uspensky's Theology of the Icon.

This work, as its title indicates, was intended to be a first attempt at such a theology. What does it actually consist of? Its main components are

Uspensky’s theological conclusions, obviously, did not cut such a bad figure (the author of these lines, not being a theologian, is unable to judge, but points out that Uspensky was not a theologian either ...). In any case, the findings of his Theology are so well licked and inspire so much confidence that we can easily understand its rapid popularity and its inclusion among the «classics» of Orthodox writing. Even Russia, Uspensky is happily cited, and statements from his book travel in the form of axioms from one popularization work to another.

Why do I say: even in Russia? We apologize for this expression. It is precisely in Russia (and perhaps only in Russia) that this Theology of the Icon, which has given such bitter fruit in Western Europe, has remained inoffensive, with no harmful effects. Without positive effects either, because Russian icon painting has always done without and still does perfectly well without this approach. How then do we explain this lack of adverse effects? To do so, let's use an analogy! At the entrance to each of the major basilicas of Rome one sees a warning sign: a figure in T-shirt and shorts, crossed out in red. Everyone understands: Don't enter here in shorts or a T-shirt! But is it really clear to everyone? Theoretically one could well imagine a Martian, a madman, or simply a nonconformist who, on seeing this panel removes his shorts and T-shirt and enters the basilica naked. Formally he would be right: the panel tells him only not to enter «in shorts.» It is we who, rooted in our Christian culture, decode this sign, not as the outright ban on shorts, but as the more general prohibition of semi-nudity even if it is allowed in other circumstances. Anyone who is aware of the obvious connection between nudity and lust, incompatible with prayer, does not need such a panel. And besides no one has ever seen this kind of signs at the entrance of Russian monasteries (which does not mean that half-naked tourists are welcome ...).

Let us explain now our analogy. A person rooted in the Orthodox icon culture, when he reads that the holy (devotional) image should not arouse the passions, will agree because he spontaneously distinguishes the passions from the other soul movements that the pious image is intended to generate. And someone for whom the Orthodox icon is a sort of exotic phenomenon will decrypt the message as being that a pious image should not arouse any «positive» emotion, and for this reason should not be attractive at all: the more repugnant, the holier it is! The first, the initiate, will be receptive to the idea that zhivopodobiye (resemblance to the living world) can potentially reduce the spiritual expressivity and power of the icon, that spiritual expressivity needs to predominate and that the art of representing the visible world must serve this expressivity and not be self-sufficient. But the same statement of zhivopodobiye potentially reducing spiritual expressivity will be transformed by the uninitiated into an outright prohibition of any resemblance to Nature, in the form of a simple equation: less resemblance = more spirituality! The thesis of the submission of the iconographer's creative ego to the tradition of the Church will be understood by the initiated as the preservation and development of the personality of the artist who follows Christ with love in the Church. But the same these will be understood by the uninitiated as the degradation and destruction of the personality in an abandonment close to that targeted by Buddhist monks. For the first the definition of iconography as a «special» art will mean Art with a capital letter, the supreme and absolute art, where all laws of artistic creation act with their primitive strength and purity. For the second, «special art» means «apart from and radically different from the general body of art.» Returning to our vestimentary analogy, where the first will read «Here you have to be dressed in a particularly decent way», the other will read «Here you can remove even your underwear.»

Uspensky wrote his work relying on the first category, but it was the second that enthusiastically took it up and misused it. He belonged to the first group of those who were able to make good bread, even with grain containing tares, as could the people around him, the group of «first wave» Russian emigrants that remained loyal to the Church. To this group we can add other artists (not just iconographers) and the public (religious or not) of contemporary Russia. This is why Uspensky's errors, inaccuracies and naivety, his fables and his far-fetched arguments do not cause that much damage in this group.

In the West, by contrast, Uspensky's book was disseminated, in particular in condensed oral or written form, in a totally different environment. This difference relates not so much to the lack of knowledge of the ancient icon, but rather the fact that the spiritual foundations of Western art have been constantly shaken apart, from top to bottom. For decades, there we have witnessed the mad commercialization of art, the cynical positioning of artists positions towards their work and audiences, the ruin of art schools, voluntarism in criticism, the loss of all reference points in aesthetic evaluation, the blurring of boundaries between the figurative, abstract and conceptual arts, between easel art and applied art, between professional art and amateur art, all false tracks that have constantly developed and strengthened and eventually become the norm.

The theories on the icon that Uspensky proposed were much appreciated by those who were wandering in this chaos, meeting the long-repressed spiritual needs of the average European, weary of cold, faceless abstract art. This European then discovers the icon, figurative art par excellence, even narrative. He has had his fill of the subjects of contemporary figurative art, of all these monkeys, dressed or naked, caring only about themselves and their pleasures. And here is the icon, the image of enlightened, deified man! He is suspicious of the ease with which the vanguard «creates» by spreading all conceivable forms of matter on its canvases. And here we have the icon with complex and painstaking technological processes! He resents today's artists, lazy and big-mouthed, living in luxury and lust. Against which Orthodoxy offers the image of the artist- ascetic!

On the other side the dissemination of Uspensky's theories was further facilitated by the fact that not only do they meet the spiritual requirements of the European, but equally they play to his spiritual laziness, his lack of discrimination, and his desire for comfort. All the diseases that have contaminated Western contemporary art have also struck the «Western» icon. And Uspensky's theology has failed to block this, even justifying these cancerous metastases that from secular art have eventually infected the icon. In the secular art of Western Europe, neither beauty, nor likeness to nature are mandatory, while for Uspensky they would if anything be harmful to the icon. To pass as an «artist» in Western Europe, one must not train seriously, nor work hard to give birth to one's personal vision of the world. The iconographer à la Uspensky does not need to either. In Western Europe, the works of a lay artist are not judged not against objective aesthetic criteria, mandatory for all, but instead his inner creative impulse is lauded above measure. Similarly, the works of self-proclaimed iconographers are not subject to any objective criticism, rather the intimate state of their souls is even excessively exalted, under the assumption, of course, that these are in a state of prayer, and passionlessness ... but try to check! There is even an art movement, Conceptualism, where there is hardly any need of the object itself, since the essential lies in the explanation. The self-proclaimed iconographer, guessing that without any concept his boards are worthless, does exactly the same thing. The only difference is that this concept he does not invent himself, he takes it off-the-peg, with indestructible validity, in the work of Uspensky.

In this context we need here to say a word about the so far little explored phenomenon of the reception of Orthodoxy in the West since the 1950s. Orthodoxy, pretty much closed in on itself until World War II, opened up widely towards the Catholic world in the immediate post-war period. The pioneer was probably Vladimir Lossky, with his Essay of the Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, first published in French in Paris in 1944, followed by Uspensky and others. Their writings were quite well received in the Western Christian intellectual world. But it is also true that those they drew were not always the best grain. From the 1970s onwards, in particular, Orthodoxy began to fascinate many people in search of spiritual renewal. For these people, many of whom shared the ideology of the New Age, tempted by its gnostic approach, Uspensky - who presented the reading of icons like deciphering an initiatory secret code -was a godsend. Among them were also people who, unfortunately, as so often in the changing world of New Age, tried to turn knowledge into hard cash.

In Western Europe, all kinds of courses and summer workshops are available to dilettantes seeking leisure activities. Everyone can learn in a week to make delicious watercolors, or bold pastels, or sparkling ceramics, or luxurious lamp shades. Iconography courses have in this way found a comfortable place in the large market for imitation art, and for the small joys of carefree expressivity. This abominable imitation that kills all real art is coupled, in the case of the icon, with a justificatory discourse erecting this method into «tradition».

And finally, the «otherness» of iconography, as distinct from the rest of the art world, played in Western Europe to the habit of using art to create little coteries of initiates, governed by a special, separate set of laws, just as, in lay art, every group and every gallery creates its own little world, treating those outside as second-rate and profane.

As these examples show, even the best-intentioned theses can be pushed to the absurd, whenever the key to their understanding is lost, whether accidentally or deliberately. And what does this key consist of?

Uspensky, in the five hundred pages of his book, did not find any place to recall the need for such a key, or even to mention its existence. Instead he has distributed a whole series of passe-partout keys, none of which opens the gate of the Garden. Even today, in Western Europe, these passe-partout keys are gaily sported: «one: trace and transfer a drawing; two: cover part of the board with gold leaf; three: recite a special prayer; four: add a dose of reverse perspective.» Yes, the lock clicks, but the gate will not open! Nor will it until someone has the courage to produce the rusty key lying around somewhere in a corner: recognizing spiritual content not in the gilding and inscription, not in the assembly of the board and in the use of egg yolk, not in the mood of the iconographer during his work, not in reverse perspective and the lack of shadows, not in the canonical scheme, but the only thing that can truly express the spiritual: the Artistic Image, more specifically that of God incarnate and man deified.

This spiritual sensitivity to the artistic image, given from above and inseparable from man, is the only hope for us, at this time of latent «new iconoclasm», as experienced by Western Christianity, Orthodox or not. The return to true Christian values in the icon will be possible only by strengthening, caring for and correcting this sensitivity. But we would like to believe, nonetheless, that theology too can contribute to this process. The current heresy has long shown its fruit: bad icon painting and its lucrative uses. Is not it time to denounce this heresy and uproot it, to clear the way for a healthy theology that will longer allow the icon to be treated any old how; which will no longer give space for the father of lies? Who knows, maybe it will be the beginning of a new teaching of the Church on art in general? The supreme function of man, the contemplation of divine harmony and participation in it, should naturally occur within the Church. It is within the Church that knowledge of this sublime function of man must crystallize. This will be the true theology of the artistic image, the theology of the icon.

[1] The Messenger (ACER) No. 151, Paris-New York-Moscow, 1987, p. 42.

[2] At the time of writing, I was able to target these reproaches at Western Europe only. Now, sadly, the disease appears to have spread to the Russian world. The plague the Russian emigration launched has reached their longed-for homeland!

An iconographer expresses him self naturally in images, and the reader will have noticed how many times that author has used stories and anecdote to make her point. We shall do the same in this chapter.

(картинка для привлечения внимания отсюда:

http://www.lsuagcenter.com/~/media/system/e/8/e/5/e8e5a2174f06374448abc7bde9347f0f/jwm_1970jpg.jpg,

как нашла красоту? а погуглила волшебное выражение «icon writing»).

Here is a story that tellingly demonstrates the current status of the icon in Western Europe: first the place of the icon in the Church and in society, and second the vision of the icon - or rather the «theology» thereof - of a handful of «specialists», whose fable-telling provides them with a livelihood and ecclesiastical and social status.

In the 1930s the church of St. John the Warrior in Meudon, a suburb of Paris, was entirely decorated by Sister Ioanna (Julia Reitlinger), a fairly well-known personality of the Russian Orthodox emigration. Endowed with a certain artistic sense, Sister Ioanna had never had any formal training as a painter, rather picking up the crumbs from under the table of Old Believer craftsmen and scenographer Dimitri Stelletsky. She had also followed for a period of three years the advice of the painter Maurice Denis, a fervent, if somewhat bourgeois Catholic, whose decorative panels were very popular at that time. In fact, we find out in her correspondence that Sister Ioanna trusted in particular in her own imagination. Father Sergei Bulgakov, the leading churchman of the Paris emigration, supported her efforts, hoping to obtain, fair from Russia, an iconographer truly worthy of the name. This hope was vain. Only rarely does Sister Ioanna attain in her work an acceptable level of mastery of the icon-painting trade. What we perceive in her is, alas, the longing for spiritual illumination, but not its attainment. Most of her works are characterized by a weak, uncertain line, volumes without modelling and unpleasant yellowish or grayish colors. His characters exhibit at times an almost aggressive nervousness, at others an effete apathy, proof of the difficulty the artist experienced in rendering human traits, whether energetic or tender, in the classical icon-painting styles. With its clumsy drawing and sad colors the decoration of the church of St. John the Warrior too testifies to a poor understanding of the artistic tradition. Only the circumstances of enforced cultural and ecclesiastical isolation in which the Russian émigrés lived can explain that it was tolerated at all.

Our purpose is not so much to dedicate ourselves to the qualitative study of Reitlinger’s works, as to the subsequent fate of her icons and murals, called for no clear reason «frescos» by her followers, even though painted on wood laminate panels. In 1960 the parish was dissolved and the church closed. We cannot attribute this sad fact only to the poverty of the decoration of the church. But neither can we deny that people coming to encounter the Absolute, Almighty and Immortal, and finding themselves in a cultural and spiritual milieu in which everything is approximate, weak and rootless, begin to doubt the Truth or to go looking for it elsewhere. Reitlinger's works do not seem to have fired the heart of the remaining Meudon parishioners, who then abandoned them to their fate. Her works were not entrusted to another parish or transferred to the domestic prayer corners of those who had worshiped and prayed in front of them for nearly thirty years. They were not even sold. The assembly of the faithful, even in this so «Russian Orthodox» corner of France, did not recognize them as carrying any spiritual or artistic or even cultural or historical value. The wider Christian world, orthodox and heterodox, remained equally indifferent. The some twenty years the abandoned church was a refuge for vagrants, with no one, as far as we can tell, ever attempting to remove and sell these Russian icons for a few francs. And this even during the «icons boom» of the 1960s, at the time of renewed interest in the icon around the world, a period of massive export (legal and illegal) of icons from Russia. At that time, Soviet publishers produced a whole series of albums, catalogs and essays on ancient Russian art. Fervent popular writers on the icon, like I. Glazunov and V. Soloukhin, enjoyed a heyday in both Russia and abroad. Andrei Tarkovsky’s famous film Andrei Rublev had just been released. In Paris, these years were marked by the publication and cascading reissues of Uspensky's Theology of the Icon, still today regarded by many as «revealed truth».

In this context of renewal, the lack of interest in the iconographic ensemble of the church of St. John the Warrior, so close to the nerve center of this revived interest, is significant. Whether because everyone had clearly perceived the «quality» of this ensemble, or the Parisian «theology of the icon» was concerned above with its own navel, no matter. The fact is that until the 1980s, the works of Reitlinger, which no one was interested in, remained in the abandoned church, since partially destroyed by fire, maybe caused by the homeless. It was only in 1980 that surviving boards were transported to the castle of Montgeron, where they remained "pending restoration.«[1] The wait lasted more than two decades. Restoration work in Western Europe is very expensive because a restorer, unlike a self-appointed «iconographer», needs to be a professional. No one had been found ready to pay to rescue works which no one had needed even when they were still in fair condition. No volunteer conservator presented himself either to save them, and since Church and art lovers were disinterested, their fate seemed sealed.

The dramatic coup de théâtre took place in 2000. Suddenly, they were once again brought back into the public eye! Not for religious or artistic reasons, but for reasons of «cultural policy». At the time of the restoration of relations between post-perestroika Russia and the Russian emigration, the descendants of the first emigrants, to illustrate the cultural and «orthodox» merits of their predecessors, brought to Russia these once despised works. An expensive exhibition was organized with all the usual trimmings (reception, publications, lectures by experts) after which the boards were donated to the Andrei Rublev museum, placing responsibility for their conservation on its team, all at the expense of the Russian Ministry of Culture.

Has this «gift» had a positive influence in Russia today, on the practice of a better knowledge of God, and better contact with Him? Has this gift substantially increased the presence of divine beauty in a country where the iconographic tradition was never interrupted, a country which boasts a host of world-famous masters, and icon-painting schools of a very high level? The reply is clear. What sense is there in this «cultural investment» and why did the Russians accept the poisoned chalice? Because on the one hand the Russians of France were keen to remind the homeland of their existence and their merits, and on the other hand former Soviets sought to sidle up to the representatives of the legendary first migration. It is clear: worldly and political interests and the race for authority and influence form the basis for these movements that are very far from the true spirit of the Church. We mention here some of the concerns of these influential circles, permeated by this «theology of the icon»:

- The attempt, unfortunately sometimes successful, to obtain historical monument status for the interior decoration of certain first emigration churches, of as pitiful level as that of St. John the Warrior. When the conservationists of the cultural heritage have their way, the church is classified, and its parishioners, regardless of their aesthetic tastes or their spiritual needs, are forced by law to preserve forever, and restore where necessary, the wall paintings which would otherwise crumble over time. Parishioners wishing to refresh the decoration of their church would find themselves answerable for their boldness before the heritage authorities.

- The regular publication of «charitable» Christmas and New Year cards that reproduce low-quality icons, the «precious reserve» of the spiritual heritage of the Russian emigration.

- The publication, in Russia and in Russian, of bulky books on the iconographic heritage of the «First Wave». If the works of Leonid Uspensky or Georgui Krug (Brother Gregory) present a certain artistic interest, attempts to associate with them those of Julia Reitlinger (Sister Ioanna), Mother (now Saint) Maria Skobtsova or T.V. Eltchaninova produce a disastrous impression. Instead of covering these painters with glory, such publications provoke the opposite result. For us the image of Mother Maria Skobtsova, recently canonized for her works of love and charity in war-time Paris, is tarnished by the revelation of the artistic weakness and tastelessness of her works. In rescuing them from oblivion, the publishers of the monograph dedicated to her «artist» creations have drawn attention to a side of her that would well have been better forgotten.

- The organization of numerous courses and summer workshops which, under the guise of teaching iconography, sell the much-coveted goods of spiritual comfort and the certainty of being «creative». Any participant, upon payment of the agreed sum and placing himself under the spiritual guidance of the course leader, receives the guarantee of being on the right spiritual path, with a deep understanding of the artistic tradition. The teaching approach varies depending on participants’ preference for (spiritual) sticks and (spiritual) carrots. What is common to all, it is the replacement of the true Orthodox theology of the icon by system of incantations worthy of a yeshiva, creative and pedagogical incompetence, wilful concealment from students of all manifestations of Christian culture, both ancient and contemporary, that could challenge the ideology of the course. The author has known persons led by people no better than crooks to prepay more than 5000 euros for a cycle of seven courses, or who have had been required to commit to turn over to their «very dear master» (in casu mistress) 10% of all income from their future icon-painting until their lives' ends. Some suckers have been sold, for astronomical sums, pigments «crushed and blessed with his own hands by a great elder » that laboratory analysis has proved to be simple industrial pigments, beautifully repackaged in old-fashioned bottles!

At the 2005 European Orthodox Congress 2005 in Blankenberge, Belgium, the author had the opportunity to get a deeper insight into the methods used in this kind of courses, by participating in the icon workshop that was proposed as part of this Congress. The presenter spent her entire time slot explaining, line by line, three «special iconographer prayers» of unknown origin. During these two days, the only object that illustrated the speaker's lectures was an unfinished icon of Christ, with a face without eyes, covered with a layer of greenish grime. The second day, the audience had changed: the first day's participants did not return.[2]

All these excesses, and others we talked about in the previous chapter, are impossible when the Church and society demand of the icon both professionalism and Beauty. Wherever this fundamental and ontological requirement is no longer applied to the icon, everything becomes possible: not only the artistic decadence of the icon, but also the elevation of this decadence to a place of tradition and norm; not only the cheating and abuse of trust of those who are looking for spiritual nourishment, but also the devaluation of the icon, and of Christian art in general, in the eyes of the European intelligentsia, both Christian and not. It is sad to see that this catastrophic situation, with the exploitation of the icon to dilettante and selfish ends, finds its basis and justification in the simplistic «theology of the icon» to which the doors were opened with the publication in French in the 1960s of Leonid Uspensky's Theology of the Icon.

This work, as its title indicates, was intended to be a first attempt at such a theology. What does it actually consist of? Its main components are

- A long historical thesis on the anti-iconoclastic struggles.

- A long and tendentious essay on the stylistic mutation of Russian art in the seventeenth century, in which Uspensky de facto accuses the Russian patriarchs of the time, and even more so the Russian Church of the Synodal period, of apostasy and of passing the monopoly of true spirituality to the Old Believers.

- A series of notes, brief, incomplete and poorly structured, on the canonical iconography.

- The author's personal views about the icon, comprising just 10% of the content of the book, with an attempt to analyse with stunning naivety the stylistic peculiarities of certain somewhat arbitrarily chosen icons.

- And finally the theological conclusions from this analysis.

Uspensky’s theological conclusions, obviously, did not cut such a bad figure (the author of these lines, not being a theologian, is unable to judge, but points out that Uspensky was not a theologian either ...). In any case, the findings of his Theology are so well licked and inspire so much confidence that we can easily understand its rapid popularity and its inclusion among the «classics» of Orthodox writing. Even Russia, Uspensky is happily cited, and statements from his book travel in the form of axioms from one popularization work to another.

Why do I say: even in Russia? We apologize for this expression. It is precisely in Russia (and perhaps only in Russia) that this Theology of the Icon, which has given such bitter fruit in Western Europe, has remained inoffensive, with no harmful effects. Without positive effects either, because Russian icon painting has always done without and still does perfectly well without this approach. How then do we explain this lack of adverse effects? To do so, let's use an analogy! At the entrance to each of the major basilicas of Rome one sees a warning sign: a figure in T-shirt and shorts, crossed out in red. Everyone understands: Don't enter here in shorts or a T-shirt! But is it really clear to everyone? Theoretically one could well imagine a Martian, a madman, or simply a nonconformist who, on seeing this panel removes his shorts and T-shirt and enters the basilica naked. Formally he would be right: the panel tells him only not to enter «in shorts.» It is we who, rooted in our Christian culture, decode this sign, not as the outright ban on shorts, but as the more general prohibition of semi-nudity even if it is allowed in other circumstances. Anyone who is aware of the obvious connection between nudity and lust, incompatible with prayer, does not need such a panel. And besides no one has ever seen this kind of signs at the entrance of Russian monasteries (which does not mean that half-naked tourists are welcome ...).

Let us explain now our analogy. A person rooted in the Orthodox icon culture, when he reads that the holy (devotional) image should not arouse the passions, will agree because he spontaneously distinguishes the passions from the other soul movements that the pious image is intended to generate. And someone for whom the Orthodox icon is a sort of exotic phenomenon will decrypt the message as being that a pious image should not arouse any «positive» emotion, and for this reason should not be attractive at all: the more repugnant, the holier it is! The first, the initiate, will be receptive to the idea that zhivopodobiye (resemblance to the living world) can potentially reduce the spiritual expressivity and power of the icon, that spiritual expressivity needs to predominate and that the art of representing the visible world must serve this expressivity and not be self-sufficient. But the same statement of zhivopodobiye potentially reducing spiritual expressivity will be transformed by the uninitiated into an outright prohibition of any resemblance to Nature, in the form of a simple equation: less resemblance = more spirituality! The thesis of the submission of the iconographer's creative ego to the tradition of the Church will be understood by the initiated as the preservation and development of the personality of the artist who follows Christ with love in the Church. But the same these will be understood by the uninitiated as the degradation and destruction of the personality in an abandonment close to that targeted by Buddhist monks. For the first the definition of iconography as a «special» art will mean Art with a capital letter, the supreme and absolute art, where all laws of artistic creation act with their primitive strength and purity. For the second, «special art» means «apart from and radically different from the general body of art.» Returning to our vestimentary analogy, where the first will read «Here you have to be dressed in a particularly decent way», the other will read «Here you can remove even your underwear.»

Uspensky wrote his work relying on the first category, but it was the second that enthusiastically took it up and misused it. He belonged to the first group of those who were able to make good bread, even with grain containing tares, as could the people around him, the group of «first wave» Russian emigrants that remained loyal to the Church. To this group we can add other artists (not just iconographers) and the public (religious or not) of contemporary Russia. This is why Uspensky's errors, inaccuracies and naivety, his fables and his far-fetched arguments do not cause that much damage in this group.

In the West, by contrast, Uspensky's book was disseminated, in particular in condensed oral or written form, in a totally different environment. This difference relates not so much to the lack of knowledge of the ancient icon, but rather the fact that the spiritual foundations of Western art have been constantly shaken apart, from top to bottom. For decades, there we have witnessed the mad commercialization of art, the cynical positioning of artists positions towards their work and audiences, the ruin of art schools, voluntarism in criticism, the loss of all reference points in aesthetic evaluation, the blurring of boundaries between the figurative, abstract and conceptual arts, between easel art and applied art, between professional art and amateur art, all false tracks that have constantly developed and strengthened and eventually become the norm.

The theories on the icon that Uspensky proposed were much appreciated by those who were wandering in this chaos, meeting the long-repressed spiritual needs of the average European, weary of cold, faceless abstract art. This European then discovers the icon, figurative art par excellence, even narrative. He has had his fill of the subjects of contemporary figurative art, of all these monkeys, dressed or naked, caring only about themselves and their pleasures. And here is the icon, the image of enlightened, deified man! He is suspicious of the ease with which the vanguard «creates» by spreading all conceivable forms of matter on its canvases. And here we have the icon with complex and painstaking technological processes! He resents today's artists, lazy and big-mouthed, living in luxury and lust. Against which Orthodoxy offers the image of the artist- ascetic!

On the other side the dissemination of Uspensky's theories was further facilitated by the fact that not only do they meet the spiritual requirements of the European, but equally they play to his spiritual laziness, his lack of discrimination, and his desire for comfort. All the diseases that have contaminated Western contemporary art have also struck the «Western» icon. And Uspensky's theology has failed to block this, even justifying these cancerous metastases that from secular art have eventually infected the icon. In the secular art of Western Europe, neither beauty, nor likeness to nature are mandatory, while for Uspensky they would if anything be harmful to the icon. To pass as an «artist» in Western Europe, one must not train seriously, nor work hard to give birth to one's personal vision of the world. The iconographer à la Uspensky does not need to either. In Western Europe, the works of a lay artist are not judged not against objective aesthetic criteria, mandatory for all, but instead his inner creative impulse is lauded above measure. Similarly, the works of self-proclaimed iconographers are not subject to any objective criticism, rather the intimate state of their souls is even excessively exalted, under the assumption, of course, that these are in a state of prayer, and passionlessness ... but try to check! There is even an art movement, Conceptualism, where there is hardly any need of the object itself, since the essential lies in the explanation. The self-proclaimed iconographer, guessing that without any concept his boards are worthless, does exactly the same thing. The only difference is that this concept he does not invent himself, he takes it off-the-peg, with indestructible validity, in the work of Uspensky.

In this context we need here to say a word about the so far little explored phenomenon of the reception of Orthodoxy in the West since the 1950s. Orthodoxy, pretty much closed in on itself until World War II, opened up widely towards the Catholic world in the immediate post-war period. The pioneer was probably Vladimir Lossky, with his Essay of the Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church, first published in French in Paris in 1944, followed by Uspensky and others. Their writings were quite well received in the Western Christian intellectual world. But it is also true that those they drew were not always the best grain. From the 1970s onwards, in particular, Orthodoxy began to fascinate many people in search of spiritual renewal. For these people, many of whom shared the ideology of the New Age, tempted by its gnostic approach, Uspensky - who presented the reading of icons like deciphering an initiatory secret code -was a godsend. Among them were also people who, unfortunately, as so often in the changing world of New Age, tried to turn knowledge into hard cash.

In Western Europe, all kinds of courses and summer workshops are available to dilettantes seeking leisure activities. Everyone can learn in a week to make delicious watercolors, or bold pastels, or sparkling ceramics, or luxurious lamp shades. Iconography courses have in this way found a comfortable place in the large market for imitation art, and for the small joys of carefree expressivity. This abominable imitation that kills all real art is coupled, in the case of the icon, with a justificatory discourse erecting this method into «tradition».

And finally, the «otherness» of iconography, as distinct from the rest of the art world, played in Western Europe to the habit of using art to create little coteries of initiates, governed by a special, separate set of laws, just as, in lay art, every group and every gallery creates its own little world, treating those outside as second-rate and profane.

As these examples show, even the best-intentioned theses can be pushed to the absurd, whenever the key to their understanding is lost, whether accidentally or deliberately. And what does this key consist of?

- The ability to perceive the spiritual content of any work of art or, more precisely, of any «artistic image».

- Demanding standards with regard to the expression of this spiritual content.

- The absolute certainty that content, this potential, are ontological for any art, and especially sacred art.

Uspensky, in the five hundred pages of his book, did not find any place to recall the need for such a key, or even to mention its existence. Instead he has distributed a whole series of passe-partout keys, none of which opens the gate of the Garden. Even today, in Western Europe, these passe-partout keys are gaily sported: «one: trace and transfer a drawing; two: cover part of the board with gold leaf; three: recite a special prayer; four: add a dose of reverse perspective.» Yes, the lock clicks, but the gate will not open! Nor will it until someone has the courage to produce the rusty key lying around somewhere in a corner: recognizing spiritual content not in the gilding and inscription, not in the assembly of the board and in the use of egg yolk, not in the mood of the iconographer during his work, not in reverse perspective and the lack of shadows, not in the canonical scheme, but the only thing that can truly express the spiritual: the Artistic Image, more specifically that of God incarnate and man deified.

This spiritual sensitivity to the artistic image, given from above and inseparable from man, is the only hope for us, at this time of latent «new iconoclasm», as experienced by Western Christianity, Orthodox or not. The return to true Christian values in the icon will be possible only by strengthening, caring for and correcting this sensitivity. But we would like to believe, nonetheless, that theology too can contribute to this process. The current heresy has long shown its fruit: bad icon painting and its lucrative uses. Is not it time to denounce this heresy and uproot it, to clear the way for a healthy theology that will longer allow the icon to be treated any old how; which will no longer give space for the father of lies? Who knows, maybe it will be the beginning of a new teaching of the Church on art in general? The supreme function of man, the contemplation of divine harmony and participation in it, should naturally occur within the Church. It is within the Church that knowledge of this sublime function of man must crystallize. This will be the true theology of the artistic image, the theology of the icon.

[1] The Messenger (ACER) No. 151, Paris-New York-Moscow, 1987, p. 42.

[2] At the time of writing, I was able to target these reproaches at Western Europe only. Now, sadly, the disease appears to have spread to the Russian world. The plague the Russian emigration launched has reached their longed-for homeland!