"It is never easy becoming the past tense." -- Woman and Scarecrow

It's rare enough that on seeing the first half of a play, you just know that you have to buy the book as soon as possible. Luckily, the Abbey and Peacock theatres tend to sell copies of the plays they're intimately involved with, so I was able to buy the script for Woman and Scarecrow during intermission. Marina Carr is a playwright with an uncompromising sense of humanity and Woman and Scarecrow is an unforgivingly powerful play -- a play that hits so hard that applause feels out of place. Out of all the wonderful theatre I've seen in the past three weeks, I think this is the play that will stick with me.

Woman and Scarecrow is a threnody for a bitter and unhappy woman. Yet of the plays I've experienced recently, this is the one that offers catharsis. It is intensely poetic, a play that first stuns you then seeps into your consciousness leaving you pondering scenes for days afterwards. Several critics have connected the play to Dylan Thomas' most famous villanelle. Another work sparking connections for me is Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich. This production is the Irish premiere of the play, which had its world premiere last year in London. Looking at the publicity stills from the London production reminds me how much a collaborative artform theatre is. The design and direction ( the director was Selina Cartmell, whose Sweeny Todd I ecstatically squeed about a few months ago) illuminated Carr's script.

The play begins with a young girl in a red coat and hat playing in the snow projected onto a scrim. The scrim rises to reveal the Woman, on her deathbed, watching her younger self now spectrally projected onto the bleak symbolic landscape of the stage. The set is stark-- Woman's deathbed is perched precariously on a snowdrift, and the walls are dark and foggy. Woman converses with her alter ego, Scarecrow, while death waits in the wardrobe.

Their conversation is periodically intruded upon by her unfaithful husband ("There are many ways to leave someone. Mine is a cliche. I lack your savagery.") and by her Auntie Ah (the representitive of a whole cadre of relations either keeping vigil or a more vulture-like deathwatch). Unlike the stark blacks and whites of Woman's interior landscape, the intrusion of humanity is bright and garish. Despite her fight to stay living for a little while longer, Woman seems to shun her connections with the outside world. Her interactions with Him and Auntie Ah are only half focused, as Scarecrow still holds her attention. While her eight children are often mentioned, they are never seen and are often mentioned as excuses or shields (with the exception of the ninth child, who died unborn).

Half the critics reviewing Woman and Scarecrow end up quoting Dylan Thomas's "Do not go gentle into that good night," and for good reason. Olwen Fouere's performance is stunning, and she does indeed rage as everything is stripped down to the nakedness of facing death. Her Woman is bitter and unforgiving, desperately vulnerable, and at times tender. Barbara Brennan's Scarecrow is a perfect partner, balancing wry humour and equal unforgiveness ("Why didn't I have more sex when I could have?" "You were too busy hoovering.") with the glamour of an alter ego who accuses Woman of sacrificing herself to mediocrity, the tenderness of Woman's only connection to her dead mother and the sinister mystique of Thanatos. The young girl in the red coat and hat, an image that Woman holds as a memory of a moment of happiness and connection with her mother, is revealed to be a false memory covering the moment of connection the girl had with her mother on her deathbed.

". . . as I stand there . . . a terrible realization comes flashing through . . . a picture from the future . . . as I stand there, I see myself here. Now. I see my own death day . . . and now she wakes and looks at me. I swim in her eye, she in mine, we're spellbound, unsmiling, conspiritors too wise to fight what has been decreed on high long ago."

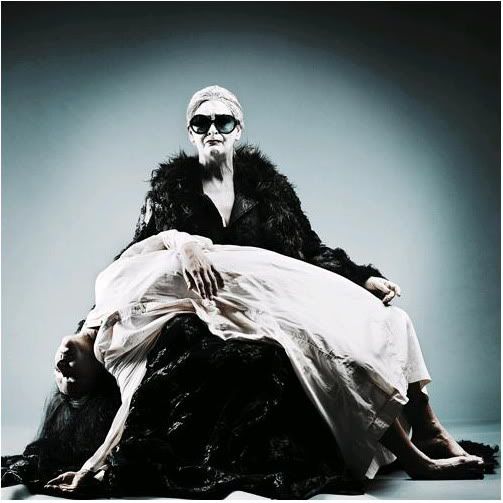

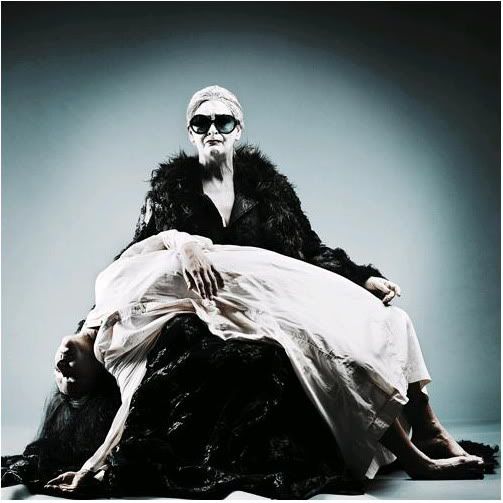

Scarecrow's role turns from that of the alter ego helping her fight death to death's angel. As Woman reaches the moment of her death, she is unclothed, cut off even from her deathbed. The play ends with a stunning echo of the Pieta.

(Publicity shot.)

I just have to include a last monologue . . . I'm just too glad to have the text, I guess.

"We don't belong here. There must be another Earth. And yet there was a moment when I thought it might be possible here. A moment so elusive it's hardly worth mentioning . . . an ordinary day with the ordinary sun of a late Indian summer shining on the grass as I sat in the car waiting to collect the children from school. Rusalka on the radio, her song to the moon, Rusalka pouring her heart out to the moon, her love for the prince, make me human, she sings, make me human so I can have him. And something about the alignment of the sun and wind and song on this most ordinary of afternoons stays with me, though what it means is beyond me and what I felt is forgotten now, but the bare facts, me the sun, the shivering grass, Rusalka singing to the moon. And I wonder is this not the prayer each of us whispers when we pause to consider. Make me human. And then divine. And I wonder is it for these elusive prayers we are here, these half sentences that vanish into the ether almost before we can utter them. Living is almost nothing and we brave little mortals investing so much in it."

Woman and Scarecrow is a threnody for a bitter and unhappy woman. Yet of the plays I've experienced recently, this is the one that offers catharsis. It is intensely poetic, a play that first stuns you then seeps into your consciousness leaving you pondering scenes for days afterwards. Several critics have connected the play to Dylan Thomas' most famous villanelle. Another work sparking connections for me is Tolstoy's The Death of Ivan Ilyich. This production is the Irish premiere of the play, which had its world premiere last year in London. Looking at the publicity stills from the London production reminds me how much a collaborative artform theatre is. The design and direction ( the director was Selina Cartmell, whose Sweeny Todd I ecstatically squeed about a few months ago) illuminated Carr's script.

The play begins with a young girl in a red coat and hat playing in the snow projected onto a scrim. The scrim rises to reveal the Woman, on her deathbed, watching her younger self now spectrally projected onto the bleak symbolic landscape of the stage. The set is stark-- Woman's deathbed is perched precariously on a snowdrift, and the walls are dark and foggy. Woman converses with her alter ego, Scarecrow, while death waits in the wardrobe.

Their conversation is periodically intruded upon by her unfaithful husband ("There are many ways to leave someone. Mine is a cliche. I lack your savagery.") and by her Auntie Ah (the representitive of a whole cadre of relations either keeping vigil or a more vulture-like deathwatch). Unlike the stark blacks and whites of Woman's interior landscape, the intrusion of humanity is bright and garish. Despite her fight to stay living for a little while longer, Woman seems to shun her connections with the outside world. Her interactions with Him and Auntie Ah are only half focused, as Scarecrow still holds her attention. While her eight children are often mentioned, they are never seen and are often mentioned as excuses or shields (with the exception of the ninth child, who died unborn).

Half the critics reviewing Woman and Scarecrow end up quoting Dylan Thomas's "Do not go gentle into that good night," and for good reason. Olwen Fouere's performance is stunning, and she does indeed rage as everything is stripped down to the nakedness of facing death. Her Woman is bitter and unforgiving, desperately vulnerable, and at times tender. Barbara Brennan's Scarecrow is a perfect partner, balancing wry humour and equal unforgiveness ("Why didn't I have more sex when I could have?" "You were too busy hoovering.") with the glamour of an alter ego who accuses Woman of sacrificing herself to mediocrity, the tenderness of Woman's only connection to her dead mother and the sinister mystique of Thanatos. The young girl in the red coat and hat, an image that Woman holds as a memory of a moment of happiness and connection with her mother, is revealed to be a false memory covering the moment of connection the girl had with her mother on her deathbed.

". . . as I stand there . . . a terrible realization comes flashing through . . . a picture from the future . . . as I stand there, I see myself here. Now. I see my own death day . . . and now she wakes and looks at me. I swim in her eye, she in mine, we're spellbound, unsmiling, conspiritors too wise to fight what has been decreed on high long ago."

Scarecrow's role turns from that of the alter ego helping her fight death to death's angel. As Woman reaches the moment of her death, she is unclothed, cut off even from her deathbed. The play ends with a stunning echo of the Pieta.

(Publicity shot.)

I just have to include a last monologue . . . I'm just too glad to have the text, I guess.

"We don't belong here. There must be another Earth. And yet there was a moment when I thought it might be possible here. A moment so elusive it's hardly worth mentioning . . . an ordinary day with the ordinary sun of a late Indian summer shining on the grass as I sat in the car waiting to collect the children from school. Rusalka on the radio, her song to the moon, Rusalka pouring her heart out to the moon, her love for the prince, make me human, she sings, make me human so I can have him. And something about the alignment of the sun and wind and song on this most ordinary of afternoons stays with me, though what it means is beyond me and what I felt is forgotten now, but the bare facts, me the sun, the shivering grass, Rusalka singing to the moon. And I wonder is this not the prayer each of us whispers when we pause to consider. Make me human. And then divine. And I wonder is it for these elusive prayers we are here, these half sentences that vanish into the ether almost before we can utter them. Living is almost nothing and we brave little mortals investing so much in it."