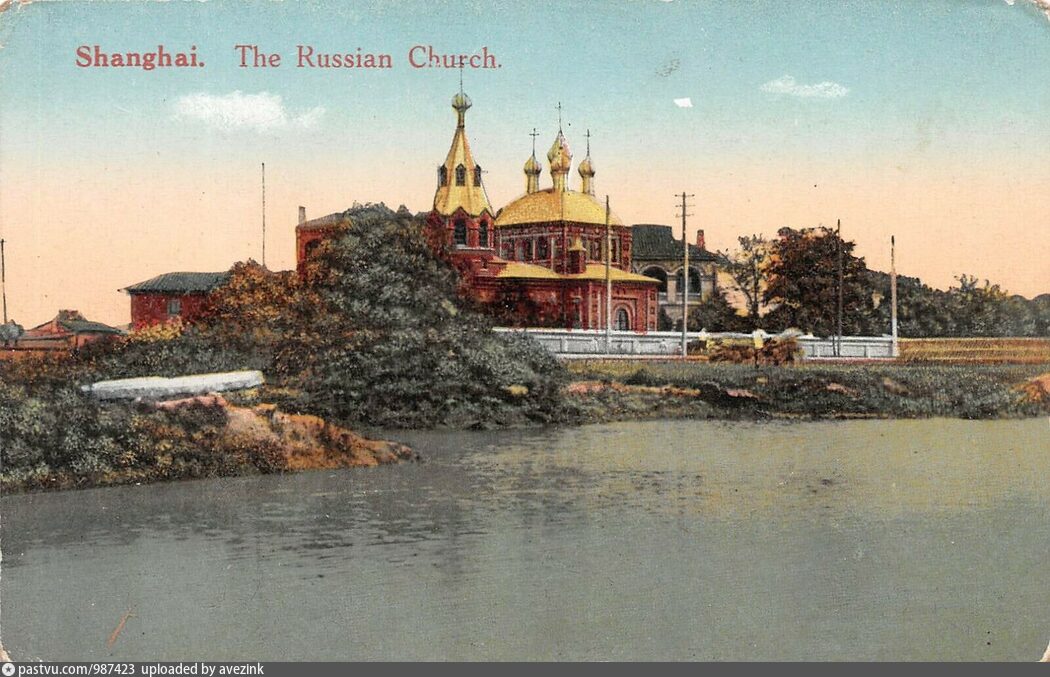

Russian Orthodox Church of the Epiphany on Paoshan Road (Богоявленская церковь)

This text is a work in progress and it will be substantially edited for my presentation in Syndey next month.

The ground was broken for the Church of the Epiphany in Paoshan district in February 1903, and the church took one and a half years to build. Upon the admission of the monks, the process lacked professional supervision and the resulting building left much to be desired. The inauguration was postponed until the end of the Russo-Japanese War and until a visit of the Archimandrite Innokentiy was scheduled; the opening took place on 1 February 1905. The neighborhood was unevenly unpopulated, penetrated by many creeks and dotted by small lakes, as shown on the images above. The last push to complete and sanctify the building happened in the connection with the arrival in Shanghai in August 1904 of several hundred refugees from Port Arthur, the northern Chinese port that capitulated to the Japanese.

Refugees from Port Arthur land in Shanghai in 1904. Image: Getty

Russian crew from Askold in Shanghai, 1904-1905. Getty.

[...]

This early Russian community mostly dissolved by 1906, leaving only several hundred immigrants in Shanghai. When refugees from the Bolshevik revolution in October 1917 began to trickle to Shanghai, the church became an anchor of the early Russian settlement in Shanghai. Dozens of refugees rented small cubbies in the mission buildings. and in March 1920, a western visitor to these homes found them inadequate: "They are living, fearfully overcrowded, in what appears to be the servants' quarters of a fairly large house. [...] The refugees rent these tiny little rooms for a small sum, all of them are in a very ramshackle condition, and the priest lives in one of them, no better and no bigger than the rest, just the kind of room our Chinese servants live in. The curious part of the whole affair is that the big house, empty, furnished, is kept unused and locked up. No one is allowed to live in any part of it, even the priest [...] by command of some church dignitary in Peking." (NCDN, 11 March 1920). Another account recalled that "in the old and dingy place on Paoshan Road there were five tiny rooms none of which scarcely was fit for one man to sleep in, let alone seven as there were one one occasion. The walls were filthy with dirt and damp stains, and the floors badly wanted covering to hide their defects." (TCP, 29 August 1926)

While living on the mission premises, Russians were desperately looking for work - and some lost all hope. In January 1920, unable to find a job to feed himself, a Russian man leaped on to the tracks in front of the moving train. The discovery of his mutilated corpse on the train tracks near the Church of the Epiphany stirred a wave of foreigners' concern for the well-being of Russian refugees. Job solicitations appeared in local newspapers, listing the professions of the refugees: 2 ships officers, 3 lawyers, 7 bridge building engineers, 4 children's nurses, 1 newspaper editor, 1 printer, 1 carpenter, 5 theatrical artistes, 4 chemists, 1 mechanical engineer, 1 monumental mason, 2 electricians, 2 motor mechanics, 2 tailors, 2 shipyard mechanics, 1 waiter, 5 sailors, 3 bookkeepers, 1 hairdresser, 2 bakers, 1 draughtsman, 5 teachers, 2 firemen, 1 engine driver, 1 ship cook, 1 boxmaker (total 65 persons with identifiable professions in search of work). One week prior, an arrangement was made for 29 men to find employment on the vessel Gwenneth heading for the Baltic Sea ports. Altogether, however, there were between two and three thousand Russian refugees in Shanghai, and the numbers were increasing.

Relief work was carried out in three locations, all fairly removed from each other - the Church of the Epiphany, the shelter near the port, at 24 Ward Road, and the former Kelly and Walsh publishing office on the Bund. The latter was a condemned building awaiting demolition, and its new owner, the HSBC, agreed to waive the rent, allowing the soup kitchen in the ramshackle structure to serve 1000 meals to refugees weekly; there was a clothing dispensary in the back rooms. This central location was considered much nearer to the refugees' settlement in the north than the older address on Bubbling Well Road, which would necessitate spending on a tram fare.

The Union of the Russian Army and Navy Men, which formed in June 1920 and derived its income from the businesses operated by its members and their wives ("stores, auto service stations, fashion salons"), sponsored the creation of a charity hostel for impoverished army men, since many were by then seen sleeping on benches in public parks. The union rented a mansion on Wangpang Road, next to the Church of the Epiphany at an exceptionally low price of 50 taels a month. "They hired a cook and furnished a dining room in the conservatory, where in the mornings tea was served with bread and butter and lunches and dinners consisted of two courses each. Starting with thirty lunches a day, one month later the kitchen was serving fifty." (Zhiganov, 1936) In the atmosphere of uncertainty, exacerbated by the severance of diplomatic ties between China and Bolshevik Russia and the stripping of the expatriate Russians of their citizenship, the military hostel was a lifeline and a social circle for stranded military Russians, where "visitors from the city" brought gifts on weekends. (Zhiganov, 1936)

The arrival of several thousands of Russians with the Imperial Siberian Fleet from Vladivostok intensified the urgency of the housing problem. The Chapei district government pleaded with foreign authorities to find shelter for the new arrivals, or else they will freeze in winter: "During the summer months they sold all their winter clothes and now have nothing left." (NCDN, 1 October 1923) These expressions of sympathy were a thin veil for the "continued uneasiness" brought on by the refugee presence in this suburban area where farmland and rural hamlets were interspersed with lucrative recreational and educational facilities, such as the Italian Circle (Circolo Italiano), a public school for boys, a golf club and the Chinese YMCA recreation ground. Taking charge of the placement of military men and their families, the Union of the Russian Army and Navy Men rented a villa at the western edge of the French Concession, at 115 Route de Zikawei, where at any given time 100-150 people were sojourning and benefitting from free or low-price meals; it remained functional until 1928. (Zhiganov, 1936) In 1928, following the relocation of the Russians to the French Concession and the simultaneous decrease of military men in need, the Union downsized its premises but improved the quality of the services provided. By 1931 it operated two dormitories in the central French Concession: one for 28-30 bachelors, and one 5-room mansion for family men.

The clash between the Nationalist troops and local warlord armies in Chapei in January 1927 made the church unusable for a while, but the Russians managed to get a restitution from the Kuomintang and restored the building. In January 1932, however, the Chapei neighborhood, where the church was situated, was in trouble again. The Japanese and the Chinese troops were engaged in urban warfare all around the church. Apparently, the Japanese forces took the church bell tower for an observation post and fired at it nonstop, and the Chinese forces responded with the fire in the same direction. People ran in the direction of the settlements, and the Russians lef too. On January 31, the last person to leave the Church of the Epiphany was the Rev. Eliah Wen. He took the cross and the sacred vessels and left the perilous area; he was thankfully unharmed. The building was not used as a church again.

[...]

This text is a work in progress and it will be substantially edited for my presentation in Syndey next month.

Here is Bishop Simon and clergy posing in front of the church:

Here is the wedding of Mr. F. Marsch and Mrs. D. Egereff that took place in the church in May 1927:

And here is a funeral procession going from the church to the cemetery; the train tracks are visible on the right:

Here is what was left of the church after the artillery fire in 1932: