Book-It 'o13! Book #18

The Fifty Books Challenge, year four! (Years one, two, three, and four just in case you're curious.) This was a secondhand find.

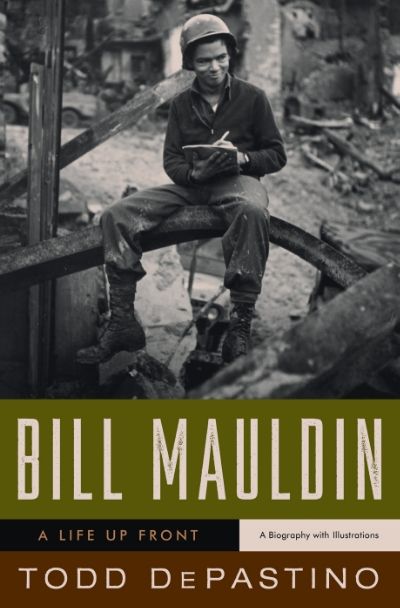

Title: Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front by Todd DePastino

Details: Copyright 2008, W. W. Norton & Company

Synopsis (By Way of Front and Back Flaps): "The definitive biography of two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Bill Mauldin, the greatest cartoonist of the Greatest Generation.

"The real war," said Walt Whitman, "will never get in the books." During World War II, the truest glimpse most Americans got of the "real war" came through the cartoons of infantry sergeant Bill Mauldin.

A self-described "desert rat" who rocket to fame at age twenty-two, Mauldin used flashing black brush lines and sardonic captions to conjure the world of the army censors, German artillery, and Patton's pledge to "throw his ass in jail" to deliver his wildly popular cartoon, "Up Front," to the pages of Stars and Stripes and hundreds of newspapers back home.

There, readers followed the story of Willie and Joe, two wisecracking "dogfaces" who mud-caked uniforms and pidgin of army slang and slum dialect bore eloquent witness to the world of combat and the men who lived-- and died-- in it. We have never viewed war in the same way since.

To combat veterans, Mauldin was the greatest hero of the war, a man who wore chips on his shoulders and lived by the motto "If it's big, hit it." Mauldin alone gave voice to the dreams, fears, and grievances of the lowly foot soldier at a time when the official spotlight was on glamorous flyers, gung-ho Marines, and members of elite units. Taken together, his 600-odd wartime cartoons, over half sketched in combat, stand as both an authentic American masterpiece and an essential chronicle of America's citizen-soldiers from peace through war to victory.

This taut, lushly illustrated biography-- the first of its kind-- contains more than ninety classic cartoons and rare photographs. Mauldin's friends and family granted author Todd DePastino access to private papers, correspondence, and thousands of original drawings in order to gain a full portrait of his extraordinary character.

The Bill Mauldin who emerges in these pages is complex, a man of multiple talents and passionate contradictions: an eccentric artist with a common touch, a charismatic adventurer who spent most of his time alone, a rebel who sought acceptance. He held powerful convictions, struggled with disillusion, and found redemption in the sense of play that infused all his work. "Here was a human being as human as they get," says friend Pat Oliphant, "growling, disgruntled, dismissive, disgusted....But when he smiled his eyes squinted up and a beam spread across his broad face from one jug ear to the other. Not many people can smile like that."

Bill Mauldin did more than sketch gags. He turned the struggle for survival into a redemptive national story. In Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front, Todd DePastino has captured a quintessential American life."

Why I Wanted to Read It: A few years ago, I read two rereleased volumes of Mauldin's cartoons (I had previously been unaware of his work) and was amazed at what a window they gave into the war. I did some research on the man himself and he was actually pretty fascinating. The fact the book is written by the same author who engineered the publishing of the two volume set (there's actually an advertising flyer in the book for the set as though it's a companion piece to the biography-- which it kind of is) gave me hope that it wasn't going to be like another biography I read of a cartoonist which was written by a biography writer rather than a fan.

How I Liked It: The book is, as promised, full of illustrations, including work from all stages of Mauldin's career, and includes photographs that shed some light on what a truly diverse life Mauldin led (in one pic, looking very Jimmy Olsen-esque, he hobnobs in post war Hollywood with Marlene Dietrich, Burgess Meredith, and Jinx Falkenberg; in another, blood trickles down his broken nose after being punched by a friend of corrupt Chicago Mayor Daley during a 1975 wedding which had the Mayor exercising his usual abuse of police power).

The book, like all the best biographies, tells a story and DePastino has clearly taken pains to make it as vivid as possible. The sheer number of sources apparently culled for various anecdotes is nothing short of impressive. The book never loses its narrative thread (unlike several other biographies we could name) and reads like a novel.

The only complaint to be made is that the focus remains largely on Mauldin's most famous period (although the author credits Mauldin's most famous cartoon as the anguished Lincoln memorial that ran after the JFK assassination), during the war (and directly after). While this is obviously the reason why many are picking up the book in the first place, this biography makes almost nothing so clear as the fact Mauldin loathed being only known for his wartime work. The book devotes a decent amount to Mauldin's transition from wartime documentarian cum cartoonist to political commentator cum cartoonist (indeed, Mauldin discovering that he actually had political opinions to illustrate) in the 1940s and it chronicles the censorship of his pro-integration cartoons that often scathed (and both cost and gained him readership).

But some of the most tumultuous and fascinating (and certainly unexamined) eras of Mauldin's life get little attention. The last chapter entitled "Fighting On (1964-2003)", manages to combine Mauldin's blood-soaked visit to Vietnam that briefly turned his sensibilities hawkish (very briefly) to his turning against the war and his almost "hippie conversion" in the late 'sixties and early 'seventies, when his opposition to Vietnam and his witness to the brutality of the Chicago police strengthened his "countercultural" leanings (frustrated over Mayor Daley's control of the Chicago media, Mauldin helped found the Chicago Journalism Review which featured a Mauldin cartoon on almost every cover), to his new marriage to a woman twenty-seven years his junior, his rise as a prominent political voice, and his slow decline and death in 2003. That's a considerable amount of time and it deserves far more, well, consideration than it's given. Only a photograph documents Mauldin's friendship with President Johnson; he was apparently a regular at the president's ranch until he turned against the Vietnam war.

Some of the more fascinating tidbits only hinted about include Mauldin's support for "counterculture start-ups like the Poor People's Campaign, feminism, and eventually gay rights" and his trip to cover the Gulf War and its affect on him (so much that he brought his most famous characters out of retirement and "drew them in desert camouflage, complete with the new American square cut helmets that reminded Bill of the Wehrmacht's.") One gets the distinct impression that the author did a considerable amount of self-editing of his own enthusiasm for the subject, and in doing so, cut down quite a bit that should've stayed. While his ambition to keep the book under a respectable three-hundred-fifty pages is admirable, about two hundred or so pages more fleshing out Mauldin's later life would've made a compelling book all the better.

Still, when you find yourself wanting to know more after reading a biography and wishing it was longer, the author has clearly paid the correct homage to the subject. This book is a fitting companion, however light, to the cartoons invaluable to the history of the second world war and of the reality of war itself.

Notable: Part of Mauldin's struggling for artistic identity after the war years covers his decision to write a memoir.

“The subject matter, he knew, was ripe. America's obsession with national security has chilled public debate, encouraging a new focus on private family life. Books like Cheaper By the Dozen (1948) and movies like Life with Father (1947) dealt with oddball family men in need of taming.” (pgs 239, 241)

To be fair, Cheaper By the Dozen is actually more a chronicle of an oddball family rather than an oddball father (although the father is certainly cast in an affectionate, occasionally oddball light) and it could be argued that Frank Gilbreth's problem wasn't a need for taming but an abundance of it (tamed into the reality of family life? Tamed into the fact he couldn't always run his family like a factory? Still).

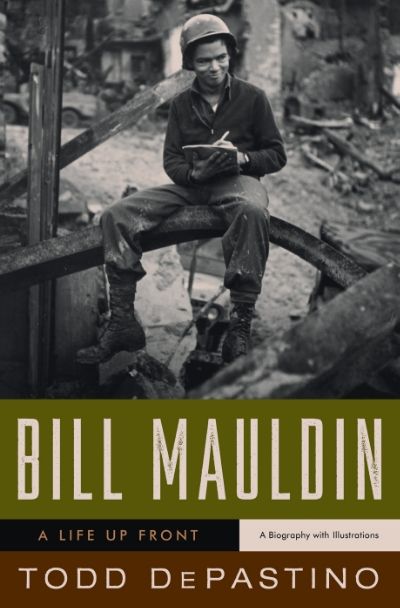

Title: Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front by Todd DePastino

Details: Copyright 2008, W. W. Norton & Company

Synopsis (By Way of Front and Back Flaps): "The definitive biography of two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Bill Mauldin, the greatest cartoonist of the Greatest Generation.

"The real war," said Walt Whitman, "will never get in the books." During World War II, the truest glimpse most Americans got of the "real war" came through the cartoons of infantry sergeant Bill Mauldin.

A self-described "desert rat" who rocket to fame at age twenty-two, Mauldin used flashing black brush lines and sardonic captions to conjure the world of the army censors, German artillery, and Patton's pledge to "throw his ass in jail" to deliver his wildly popular cartoon, "Up Front," to the pages of Stars and Stripes and hundreds of newspapers back home.

There, readers followed the story of Willie and Joe, two wisecracking "dogfaces" who mud-caked uniforms and pidgin of army slang and slum dialect bore eloquent witness to the world of combat and the men who lived-- and died-- in it. We have never viewed war in the same way since.

To combat veterans, Mauldin was the greatest hero of the war, a man who wore chips on his shoulders and lived by the motto "If it's big, hit it." Mauldin alone gave voice to the dreams, fears, and grievances of the lowly foot soldier at a time when the official spotlight was on glamorous flyers, gung-ho Marines, and members of elite units. Taken together, his 600-odd wartime cartoons, over half sketched in combat, stand as both an authentic American masterpiece and an essential chronicle of America's citizen-soldiers from peace through war to victory.

This taut, lushly illustrated biography-- the first of its kind-- contains more than ninety classic cartoons and rare photographs. Mauldin's friends and family granted author Todd DePastino access to private papers, correspondence, and thousands of original drawings in order to gain a full portrait of his extraordinary character.

The Bill Mauldin who emerges in these pages is complex, a man of multiple talents and passionate contradictions: an eccentric artist with a common touch, a charismatic adventurer who spent most of his time alone, a rebel who sought acceptance. He held powerful convictions, struggled with disillusion, and found redemption in the sense of play that infused all his work. "Here was a human being as human as they get," says friend Pat Oliphant, "growling, disgruntled, dismissive, disgusted....But when he smiled his eyes squinted up and a beam spread across his broad face from one jug ear to the other. Not many people can smile like that."

Bill Mauldin did more than sketch gags. He turned the struggle for survival into a redemptive national story. In Bill Mauldin: A Life Up Front, Todd DePastino has captured a quintessential American life."

Why I Wanted to Read It: A few years ago, I read two rereleased volumes of Mauldin's cartoons (I had previously been unaware of his work) and was amazed at what a window they gave into the war. I did some research on the man himself and he was actually pretty fascinating. The fact the book is written by the same author who engineered the publishing of the two volume set (there's actually an advertising flyer in the book for the set as though it's a companion piece to the biography-- which it kind of is) gave me hope that it wasn't going to be like another biography I read of a cartoonist which was written by a biography writer rather than a fan.

How I Liked It: The book is, as promised, full of illustrations, including work from all stages of Mauldin's career, and includes photographs that shed some light on what a truly diverse life Mauldin led (in one pic, looking very Jimmy Olsen-esque, he hobnobs in post war Hollywood with Marlene Dietrich, Burgess Meredith, and Jinx Falkenberg; in another, blood trickles down his broken nose after being punched by a friend of corrupt Chicago Mayor Daley during a 1975 wedding which had the Mayor exercising his usual abuse of police power).

The book, like all the best biographies, tells a story and DePastino has clearly taken pains to make it as vivid as possible. The sheer number of sources apparently culled for various anecdotes is nothing short of impressive. The book never loses its narrative thread (unlike several other biographies we could name) and reads like a novel.

The only complaint to be made is that the focus remains largely on Mauldin's most famous period (although the author credits Mauldin's most famous cartoon as the anguished Lincoln memorial that ran after the JFK assassination), during the war (and directly after). While this is obviously the reason why many are picking up the book in the first place, this biography makes almost nothing so clear as the fact Mauldin loathed being only known for his wartime work. The book devotes a decent amount to Mauldin's transition from wartime documentarian cum cartoonist to political commentator cum cartoonist (indeed, Mauldin discovering that he actually had political opinions to illustrate) in the 1940s and it chronicles the censorship of his pro-integration cartoons that often scathed (and both cost and gained him readership).

But some of the most tumultuous and fascinating (and certainly unexamined) eras of Mauldin's life get little attention. The last chapter entitled "Fighting On (1964-2003)", manages to combine Mauldin's blood-soaked visit to Vietnam that briefly turned his sensibilities hawkish (very briefly) to his turning against the war and his almost "hippie conversion" in the late 'sixties and early 'seventies, when his opposition to Vietnam and his witness to the brutality of the Chicago police strengthened his "countercultural" leanings (frustrated over Mayor Daley's control of the Chicago media, Mauldin helped found the Chicago Journalism Review which featured a Mauldin cartoon on almost every cover), to his new marriage to a woman twenty-seven years his junior, his rise as a prominent political voice, and his slow decline and death in 2003. That's a considerable amount of time and it deserves far more, well, consideration than it's given. Only a photograph documents Mauldin's friendship with President Johnson; he was apparently a regular at the president's ranch until he turned against the Vietnam war.

Some of the more fascinating tidbits only hinted about include Mauldin's support for "counterculture start-ups like the Poor People's Campaign, feminism, and eventually gay rights" and his trip to cover the Gulf War and its affect on him (so much that he brought his most famous characters out of retirement and "drew them in desert camouflage, complete with the new American square cut helmets that reminded Bill of the Wehrmacht's.") One gets the distinct impression that the author did a considerable amount of self-editing of his own enthusiasm for the subject, and in doing so, cut down quite a bit that should've stayed. While his ambition to keep the book under a respectable three-hundred-fifty pages is admirable, about two hundred or so pages more fleshing out Mauldin's later life would've made a compelling book all the better.

Still, when you find yourself wanting to know more after reading a biography and wishing it was longer, the author has clearly paid the correct homage to the subject. This book is a fitting companion, however light, to the cartoons invaluable to the history of the second world war and of the reality of war itself.

Notable: Part of Mauldin's struggling for artistic identity after the war years covers his decision to write a memoir.

“The subject matter, he knew, was ripe. America's obsession with national security has chilled public debate, encouraging a new focus on private family life. Books like Cheaper By the Dozen (1948) and movies like Life with Father (1947) dealt with oddball family men in need of taming.” (pgs 239, 241)

To be fair, Cheaper By the Dozen is actually more a chronicle of an oddball family rather than an oddball father (although the father is certainly cast in an affectionate, occasionally oddball light) and it could be argued that Frank Gilbreth's problem wasn't a need for taming but an abundance of it (tamed into the reality of family life? Tamed into the fact he couldn't always run his family like a factory? Still).