Book-It 'o13! Book #10

The Fifty Books Challenge, year four! (Years one, two, three, and four just in case you're curious.) This was a library request.

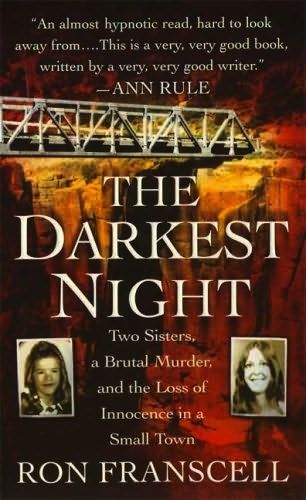

Title: The Darkest Night: Two Sisters, a Brutal Murder, and the Loss of Innocence in a Small Town by Ron Franscell

Details: Copyright 2007, St. Martin's True Crime

Synopsis (By Way of Back Cover): "ONE CAR RIDE. TWO YOUNG SISTERS. A BRUTAL FATE.

Casper, Wyoming: 1973. Eleven-year-old Amy Burridge rides with her eighteen-year-old sister, Becky, to the grocery store. When they finish their shopping, Becky's car gets a flat tire. Two men politely offer them a ride home. But they were anything but Good Samaritans. The girls would suffer unspeakable crimes at the hands of these men before being thrown from a bridge into the North Platte River. One miraculously survived. The other did not.

A CRIME THAT TORE A SMALL TOWN APART.

Years later, author and journalist Ron Franscell--who lived in Casper at the time of the crime, and was a friend to Amy and Becky--can't forget Wyoming's most shocking story of abduction, rape, and murder. Neither could Becky, the surviving sister. The two men who violated her and Amy were sentenced to life in prison, but the demons of her past kept haunting Becky...until she met her fate years later at the same bridge where she'd lost her sister."

Why I Wanted to Read It: This was recommended to me after finishing Damien Echols's memoir.

How I Liked It: From the cover and the packaging, this book looks like the often-screaming, low information paperback nonsense that's generally rushed to press and forgotten. Save for, of course, several notable positive blurbs, including one from crime literature icon Ann Rule which appears above the title:

“An almost hypnotic read, hard to look away from... This is a very, very good book, written by a very, very good writer.”

I was hopeful that Ms Rule's endorsement would prove to be true. Thankfully, it was.

While the book is not without its missteps, it reads as richly as a novel, ions away from the paperback nonsense it may outwardly resemble. Franscell's personal stake runs deep, but he manages to temper it just enough to keep it as a framing device, rather than overwhelming the story.

Apparently Franscell, while paging through a magazine on a plane a few months after September 11th, was triggered by one of the infamous photos of the falling victims from the towers. This particular photo that Franscell stumbled upon was of two victims holding hands as they fell. He's immediately reminded of a true horror story from his childhood, about one bridge, two sisters, and a haunting, horrible fate that seemed to forever cast shadow on his hometown.

Franscell lushly sets each scene, from the surviving victim's horrific plunge and recovery to the distinct Wyoming wind that encapsulated his childhood to the palpable unease and groundswell rage of the town in the aftermath. His dialog largely relies on educated suggestion (a wise move) rather than imagination, and it's extremely effective.

Another laudable maneuver: Francsell ponders larger themes spawned from the incident, but manages to do so in a way that is actually food for thought, rather than the overwrought filler that such writing can easily become.

The book is truly as Rule christens it from the cover: mesmerizing and a page-turner from start to finish.

Notable: In his vivid storytelling, Franscell commits a Boomer sin (a sin distinctive to that generation, not an act generally considered to be a sin by that generation) and one of my great pet peeves as a cultural anthropology enthusiast. He claims the innocence of the "good ol' days," under which his childhood conveniently fell, and tries to back it up as fact. Here, he compares the time of the incident (fall of 1973) to the modern day (at the time of the writing, 2007):

“But we thought we were invincible. None of us had died. We understood the theory, but dismissed the reality. In that way, we were probably not much different from most small-town kids in the guiltless years before videogames, twenty-four-hour cable news, Columbine, the Internet, graphic prime-time violence, embedded war correspondents, gangsta rap and mass cynicism. ” (pg 10)

Let us remove ourselves from Franscell's fictitious halcyon for a moment. 1973 from 2007. So let us picture in 1973, an author reflecting on his childhood thirty-four years prior, in 1939. Ready?

"In that way, we were probably not much different from most small-town kids in the guiltless years before drugs, Watergate, Woodstock, Vietnam, television, World War II, hippies and beatniks, rock 'n' roll and war protesting."

I could go thirty-four years from 1939 and continue on from there, imagining a writer musing on his childhood in 1905. While globalization is no doubt a reality as is the fact its reach strengthens by each year, one must (particularly as a journalist) keep some sense of perspective.

The second stretch of text that earned my side-eye has darker implications. Franscell recalls infamous horrific crimes in Wyoming, perhaps most well-known being the torture and murder of Matthew Shepard.

“The 1998 crucifixion of gay student Matthew Shepard on a buck rail fence near Laramie by two homophobic slacker punks comes closest to the monstrosity of the crimes against Amy Burridge and Becky Thomson. While gay hate-crimes unfolded with regularity elsewhere, the circumstances and settings of this one shocked a cable-news nation. The resulting news deluge became more about homophobia in the Heartland than about the grisly killing of an innocent boy who never hurt anyone.

When his murder morphed into a story about Wyoming's alleged gay bias- at least, that's how it was perceived in Wyoming- hungry reporters and breathless gay activists seemed to lose sight of the ghastly crime and how it shocked Wyoming, too. It was good footage and fund-raising fodder for gay-rights groups, but fewer gay hate-crimes have been committed per capita in Wyoming than in San Francisco, Miami or New York City. Countless television movies, plays and news broadcasts later, Matthew Shepard became an inanimate symbol, his humanity all but dissolved in the circus that followed.” (pgs 265 and 266)

While the author is shedding tears for the perceived bias we mean ol' Queers have against poor ol' Wyoming, he overlooks the fact that while Wyoming may have fewer reported hate crimes than the large cities he named (I'd assume he was making some reference to Queer meccas by starting with San Francisco, but what is Miami really doing in there?), there's a reason why there are fewer. The population, which he mentions in other sections of the book, is considerably lower, making Wyoming one of the least-populated states in the nation, and therefore not really subject to the comparison Franscell is making.

While he's also slinging hate for "breathless gay activists" for plundering Matthew Shepard for our nefarious and selfish ends, he appears to forget that it was Shepard's parents who founded the foundation that bears his name, determined that their son not be just another statistic but a martyr, whose death would not be in vain. While the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act had yet to be signed at the time of the book's publication, the awareness of LGBTQ hate crimes was vastly expanded thanks to the efforts of Shepard's parents. Also, the idea that the torture and murder of an innocent young man for the crime of being gay would be thought of as "good" in any capacity by "gay activists" is blatantly offensive and willfully ignorant.

This is a dark stain on what is otherwise an excellent and compelling work of crime documentation.

Title: The Darkest Night: Two Sisters, a Brutal Murder, and the Loss of Innocence in a Small Town by Ron Franscell

Details: Copyright 2007, St. Martin's True Crime

Synopsis (By Way of Back Cover): "ONE CAR RIDE. TWO YOUNG SISTERS. A BRUTAL FATE.

Casper, Wyoming: 1973. Eleven-year-old Amy Burridge rides with her eighteen-year-old sister, Becky, to the grocery store. When they finish their shopping, Becky's car gets a flat tire. Two men politely offer them a ride home. But they were anything but Good Samaritans. The girls would suffer unspeakable crimes at the hands of these men before being thrown from a bridge into the North Platte River. One miraculously survived. The other did not.

A CRIME THAT TORE A SMALL TOWN APART.

Years later, author and journalist Ron Franscell--who lived in Casper at the time of the crime, and was a friend to Amy and Becky--can't forget Wyoming's most shocking story of abduction, rape, and murder. Neither could Becky, the surviving sister. The two men who violated her and Amy were sentenced to life in prison, but the demons of her past kept haunting Becky...until she met her fate years later at the same bridge where she'd lost her sister."

Why I Wanted to Read It: This was recommended to me after finishing Damien Echols's memoir.

How I Liked It: From the cover and the packaging, this book looks like the often-screaming, low information paperback nonsense that's generally rushed to press and forgotten. Save for, of course, several notable positive blurbs, including one from crime literature icon Ann Rule which appears above the title:

“An almost hypnotic read, hard to look away from... This is a very, very good book, written by a very, very good writer.”

I was hopeful that Ms Rule's endorsement would prove to be true. Thankfully, it was.

While the book is not without its missteps, it reads as richly as a novel, ions away from the paperback nonsense it may outwardly resemble. Franscell's personal stake runs deep, but he manages to temper it just enough to keep it as a framing device, rather than overwhelming the story.

Apparently Franscell, while paging through a magazine on a plane a few months after September 11th, was triggered by one of the infamous photos of the falling victims from the towers. This particular photo that Franscell stumbled upon was of two victims holding hands as they fell. He's immediately reminded of a true horror story from his childhood, about one bridge, two sisters, and a haunting, horrible fate that seemed to forever cast shadow on his hometown.

Franscell lushly sets each scene, from the surviving victim's horrific plunge and recovery to the distinct Wyoming wind that encapsulated his childhood to the palpable unease and groundswell rage of the town in the aftermath. His dialog largely relies on educated suggestion (a wise move) rather than imagination, and it's extremely effective.

Another laudable maneuver: Francsell ponders larger themes spawned from the incident, but manages to do so in a way that is actually food for thought, rather than the overwrought filler that such writing can easily become.

The book is truly as Rule christens it from the cover: mesmerizing and a page-turner from start to finish.

Notable: In his vivid storytelling, Franscell commits a Boomer sin (a sin distinctive to that generation, not an act generally considered to be a sin by that generation) and one of my great pet peeves as a cultural anthropology enthusiast. He claims the innocence of the "good ol' days," under which his childhood conveniently fell, and tries to back it up as fact. Here, he compares the time of the incident (fall of 1973) to the modern day (at the time of the writing, 2007):

“But we thought we were invincible. None of us had died. We understood the theory, but dismissed the reality. In that way, we were probably not much different from most small-town kids in the guiltless years before videogames, twenty-four-hour cable news, Columbine, the Internet, graphic prime-time violence, embedded war correspondents, gangsta rap and mass cynicism. ” (pg 10)

Let us remove ourselves from Franscell's fictitious halcyon for a moment. 1973 from 2007. So let us picture in 1973, an author reflecting on his childhood thirty-four years prior, in 1939. Ready?

"In that way, we were probably not much different from most small-town kids in the guiltless years before drugs, Watergate, Woodstock, Vietnam, television, World War II, hippies and beatniks, rock 'n' roll and war protesting."

I could go thirty-four years from 1939 and continue on from there, imagining a writer musing on his childhood in 1905. While globalization is no doubt a reality as is the fact its reach strengthens by each year, one must (particularly as a journalist) keep some sense of perspective.

The second stretch of text that earned my side-eye has darker implications. Franscell recalls infamous horrific crimes in Wyoming, perhaps most well-known being the torture and murder of Matthew Shepard.

“The 1998 crucifixion of gay student Matthew Shepard on a buck rail fence near Laramie by two homophobic slacker punks comes closest to the monstrosity of the crimes against Amy Burridge and Becky Thomson. While gay hate-crimes unfolded with regularity elsewhere, the circumstances and settings of this one shocked a cable-news nation. The resulting news deluge became more about homophobia in the Heartland than about the grisly killing of an innocent boy who never hurt anyone.

When his murder morphed into a story about Wyoming's alleged gay bias- at least, that's how it was perceived in Wyoming- hungry reporters and breathless gay activists seemed to lose sight of the ghastly crime and how it shocked Wyoming, too. It was good footage and fund-raising fodder for gay-rights groups, but fewer gay hate-crimes have been committed per capita in Wyoming than in San Francisco, Miami or New York City. Countless television movies, plays and news broadcasts later, Matthew Shepard became an inanimate symbol, his humanity all but dissolved in the circus that followed.” (pgs 265 and 266)

While the author is shedding tears for the perceived bias we mean ol' Queers have against poor ol' Wyoming, he overlooks the fact that while Wyoming may have fewer reported hate crimes than the large cities he named (I'd assume he was making some reference to Queer meccas by starting with San Francisco, but what is Miami really doing in there?), there's a reason why there are fewer. The population, which he mentions in other sections of the book, is considerably lower, making Wyoming one of the least-populated states in the nation, and therefore not really subject to the comparison Franscell is making.

While he's also slinging hate for "breathless gay activists" for plundering Matthew Shepard for our nefarious and selfish ends, he appears to forget that it was Shepard's parents who founded the foundation that bears his name, determined that their son not be just another statistic but a martyr, whose death would not be in vain. While the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act had yet to be signed at the time of the book's publication, the awareness of LGBTQ hate crimes was vastly expanded thanks to the efforts of Shepard's parents. Also, the idea that the torture and murder of an innocent young man for the crime of being gay would be thought of as "good" in any capacity by "gay activists" is blatantly offensive and willfully ignorant.

This is a dark stain on what is otherwise an excellent and compelling work of crime documentation.