Book-It 'o12! Book #36

The Fifty Books Challenge, year three! (Years one, two, and three just in case you're curious.) This was a library request.

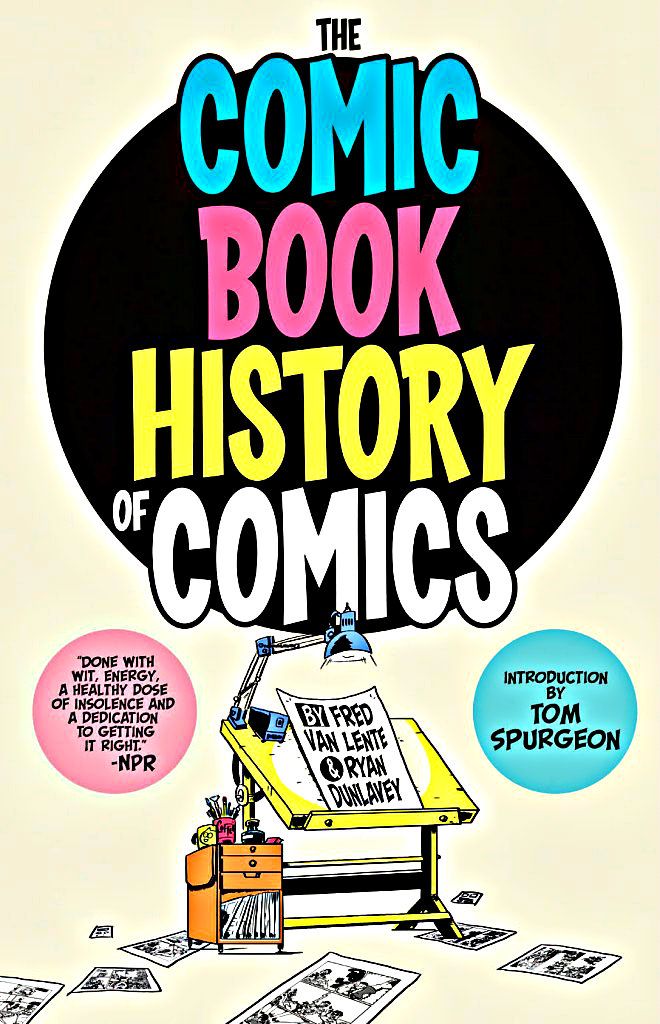

Title: Comic Book History of Comics written by Fred Van Lente and illustrated by Ryan Dunlavey

Details: Copyright 2012, IDW Publishing

Synopsis (By Way of Publisher's Information): "For the first time ever, the inspiring, infuriating, and utterly insane story of comics, graphic novels, and manga is presented in comic book form! The award-winning Action Philosophers team of Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey turn their irreverent-but-accurate eye to the stories of Jack Kirby, R. Crumb, Harvey Kurtzman, Alan Moore, Stan Lee, Will Eisner, Fredric Wertham, Roy Lichtenstein, Art Spiegelman, Herge, Osamu Tezuka - and more!"

Why I Wanted to Read It: This turned up on the old semi-reliable AV Club Comics Panel.

How I Liked It: The book is actually a misnomer. It's a history of comic books, not comics (think the newspaper variety).

The book has several flaws. For one, for this style of reference, one really needs the cleaner lines of perhaps Josh Neufeld (I'm going in favor of his fine work in that reference and history book in particular). Instead, we get what often feels like an imitation of a hokier comic style (think of the archetypal artist at the beach/carnival selling "portraits" to tourists). The various translations of other styles (Disney, R. Crumb) through this singular style as it covers them factually is moderately impressive, but the fact the general quality is so off it comes as only somewhat a relief we are spared for a bit from the slap-dash.

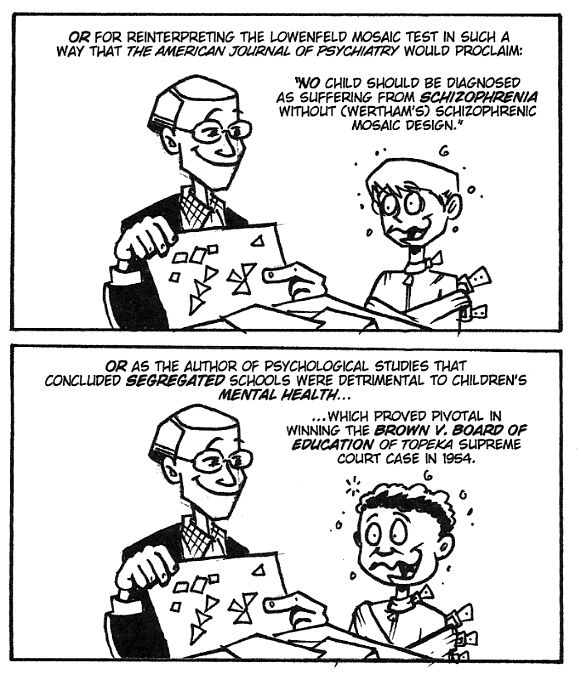

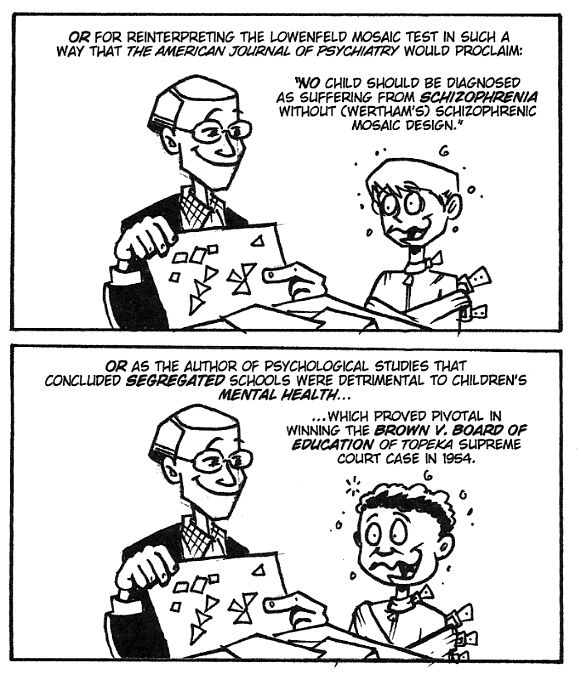

As for the narrative, it often feels as though the artist is wandering off, sketching on his own mood while the book is trying to dictate. One such example comes to mind on page seventy-nine where the biography of Doctor Fredric Wertham is given, specifically his legacy. According to the book, the doctor was a pioneer of neurobiology, psychiatry (including his work in proving segregated schools were detrimental to the mental health of children, a testimony that was apparently pivotal in Brown versus the Board of Education). The point of the narrative is that Wertham had an incredible and laudable career doing things other than making himself a formidable (and infamous) enemy of comic books and thus to generations of children anywhere.

So how is Wetham depicted while he is at perhaps his most noble, in his legitimate work with children's mental health (including examining the effects of segregation and helping to end one of our country's most disgraceful practices)?

Aside from being staggeringly ableist (why yes, that is the mentally ill, including a child suffering from the effects of segregation ((how hilarious!)), depicted as straight-jacketed and twitching, crazed grins on their faces) it comes off as distracting, like the artist was trying to either out-do the writer (narrator) or just lacking in depth (the book didn't trust the reader to stay for the text alone, the illustrations had to be a joke in every panel, whether it distracted from the information trying to be conveyed or not).

Other problems include the book too-frequently stretching too wide a swath to give an idea of the times in which the medium is competing. A considerable portion of the book is dedicated to the animation wars between Walt Disney and Max Fleisher, which, while they are tangentially related to the art of the comic book, don't really have to do with it directly.

The book leaps around unevenly through time and the disconnect between narration and art makes it even more difficult to follow.

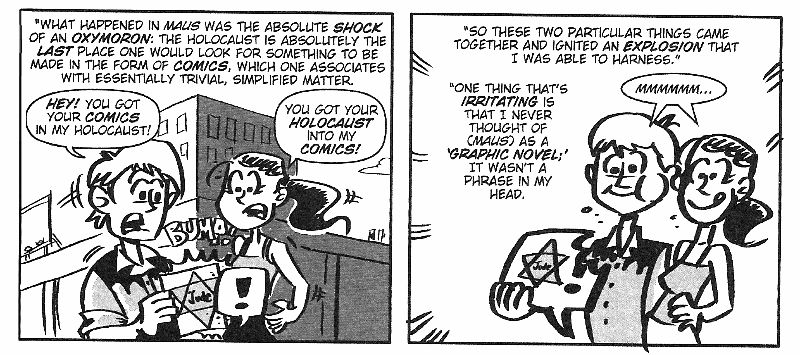

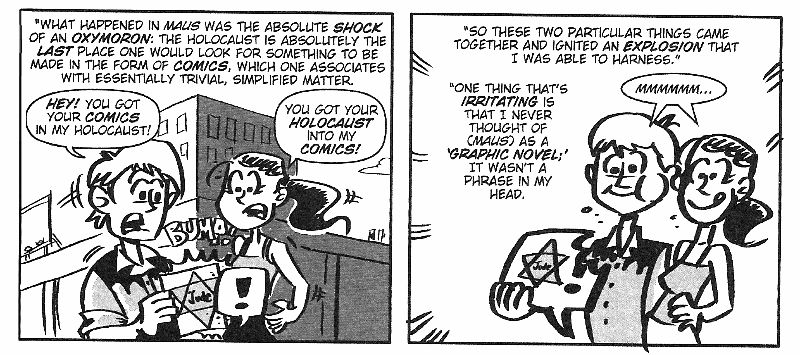

The book has its designated heroes, among them Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, and (to no one's surprise) Stan Lee. Understated (although it warrants a few pages) is the incredible impact Art Spiegelman's Maus had on the formation of the "graphic novel" genre (and the legitimization of the "comics" medium with its Pulitzer). And too easily is that section cast as obnoxiously as much of the book. The book quotes Spiegelman's marveling over the success of his choice of medium in which to tell the story of his parents survival of the Holocaust:

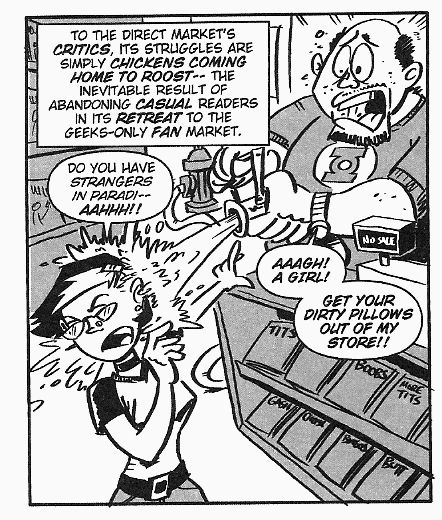

The book also plants its creators firmly in a very myopic past. Aside from its late-Boomeresque mistrust of the digital age that ranges from dopey (when discussing the evolution of a theoretical superhero through the decades, he fights WWII in the Golden Age of comics, the cold war in the Silver Age, and presumably al-Qaeda in the "modern" age, but while "Twittering about it on Facebook!") to not-that-accurate (the book postulates "comic book piracy" as on par with piracy of other mediums in frequency-- and all along you probably just thought it was the fact so many authors and artists have a way to freely present their media to the public but without a real sales model!).

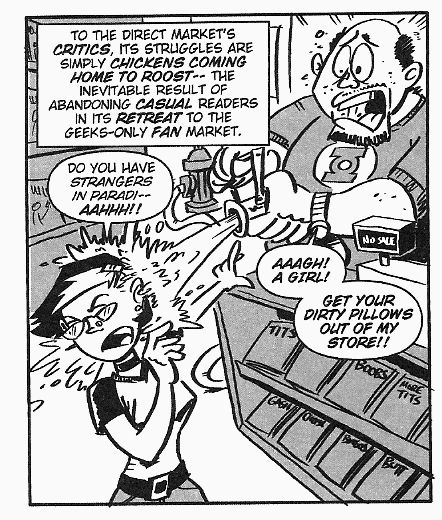

But clumsiest of these is the incorrect and, if we want to clean it up, "old-fashioned" (although from the beginning, it's never been actually true) belief that comic book enthusiasts are, like most of their artists and writers, men:

It could be argued that that's an accurate panel; surely the "traditional" comic book store isn't the most welcoming place to women? Okay, but consider the narration versus the panel: why is a female depicted as the "casual" reader? Why are women and girls apparently not considered "geeks" in the "geeks only" atmosphere? You could argue that it's just poorly worded, perhaps; possible, better rewrite: "To the direct market's critics, its struggles are merely chickens coming home to roost-- the inevitable result of abandoning the idea of an inclusive atmosphere in favor of one that caters to a select few."

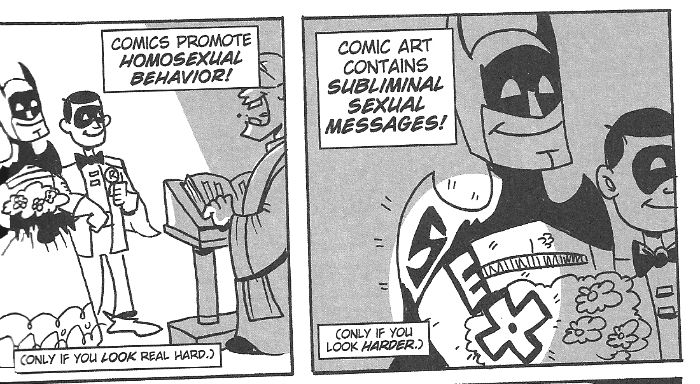

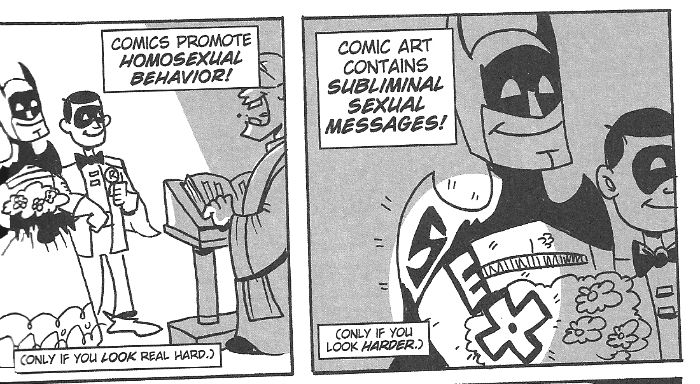

But the book comes off as (distractingly) dated in other ways. When examining the charges leveled at comic books by foe Doctor Fredric Wertham (who we met above) in his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent: the Influence of Comic Books on Today's Youth, the book examines the "comics promote homosexual behavior charge" thusly:

Why yes, that's Batman and Robin getting married. Nothing new in the trope that Batman and Robin are not-so-closeted, but you'll notice that Batman is attired in a wedding dress. At the time of the book's publication (this year), several states in this country recognize legal same-sex marriage, with more on the coming ballot. Same-sex couples abound on popular television and popular films. Even popular comic bookss now feature same-sex marriages! (Archie introduced its first openly LGBTQ character in 2011, Kevin Keller, who happened to also be an active duty military officer, and had him marrying his boyfriend the same year, while Marvel Comics introduced openly gay superhero Northstar and his wedding this past year. Even DC Comics has gotten in on the diversity by revamping old characters in a new series including Green Lantern, who now happens to be openly gay.)

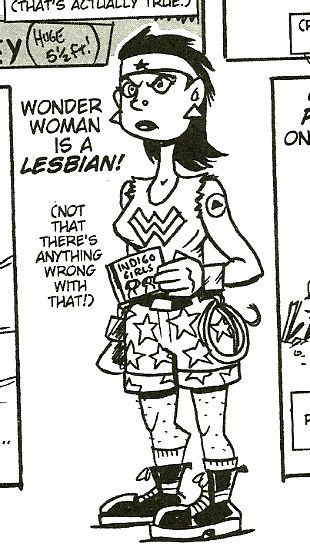

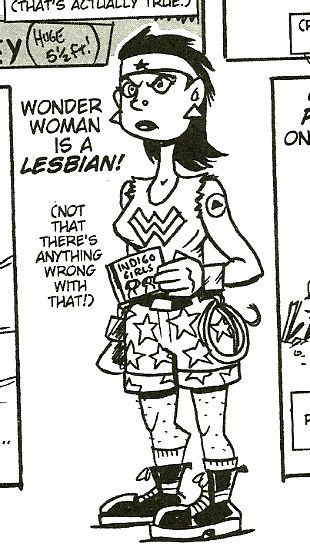

So why on earth is a same-sex wedding depicted in this day and age as one of a male couple having to "be the woman", complete with frilly gown and floral bouquet? You might make the argument that the book is trying to tap into the mindset of the period (although I'm pretty sure anti-gay forces in the 1950s didn't actually get so far as legally recognized same-sex marriage in their perceived horrors of homosexuality), save for a likewise obnoxious stereotype paired with the charge that Wonder Woman is actually a lesbian:

The combat boots, the Indigo Girls CD, and even the Seinfeld reference firmly plant (and paint) the accusation as a stereotype at least a decade and a half old. The stereotype isn't even up to date, either now or by a 1950s standard (given the anti-gay propaganda I've seen, a more accurate lesbian stereotype from the '50s might have Wonder Woman depicted in men's clothing and blatantly ignoring a plethora of male suitors whilst openly attempting to seduce unwilling "normal" women, the more attractive the better-- you know, the stereotype of the predatory homosexual "infecting" others with their illness, in this case perfectly good females that are thus being stolen from men).

The book's jumbled and inconsistent timeline makes it not really redeeming as even a primer to adults, let alone for kids, with enough "inappropriate-am-I-making-you-laugh-yet? I'm-so-bored-with-this-illustrating-stuff!" references aside from the various stereotypes we've seen.

The best thing that can be said about this book is the fact it has so much promise in its premise yet is so poorly done it almost begs for a proper execution of the idea.

Notable: In the chapter where the book (frequently inaccurately) considers the current market place under the influence of the internet, "The Oatmeal" creator Matthew Inman gets a mention as finding a successful profit model from his cartoons through merchandise sales (of course there's always the fact that Inman's work isn't really in the same "comic book" medium as put forth here any more than "Dilbert" or "The Far Side", but to be fair, the book is more or less speaking generally of artists' ways of making money from their creations via the internet).

Title: Comic Book History of Comics written by Fred Van Lente and illustrated by Ryan Dunlavey

Details: Copyright 2012, IDW Publishing

Synopsis (By Way of Publisher's Information): "For the first time ever, the inspiring, infuriating, and utterly insane story of comics, graphic novels, and manga is presented in comic book form! The award-winning Action Philosophers team of Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey turn their irreverent-but-accurate eye to the stories of Jack Kirby, R. Crumb, Harvey Kurtzman, Alan Moore, Stan Lee, Will Eisner, Fredric Wertham, Roy Lichtenstein, Art Spiegelman, Herge, Osamu Tezuka - and more!"

Why I Wanted to Read It: This turned up on the old semi-reliable AV Club Comics Panel.

How I Liked It: The book is actually a misnomer. It's a history of comic books, not comics (think the newspaper variety).

The book has several flaws. For one, for this style of reference, one really needs the cleaner lines of perhaps Josh Neufeld (I'm going in favor of his fine work in that reference and history book in particular). Instead, we get what often feels like an imitation of a hokier comic style (think of the archetypal artist at the beach/carnival selling "portraits" to tourists). The various translations of other styles (Disney, R. Crumb) through this singular style as it covers them factually is moderately impressive, but the fact the general quality is so off it comes as only somewhat a relief we are spared for a bit from the slap-dash.

As for the narrative, it often feels as though the artist is wandering off, sketching on his own mood while the book is trying to dictate. One such example comes to mind on page seventy-nine where the biography of Doctor Fredric Wertham is given, specifically his legacy. According to the book, the doctor was a pioneer of neurobiology, psychiatry (including his work in proving segregated schools were detrimental to the mental health of children, a testimony that was apparently pivotal in Brown versus the Board of Education). The point of the narrative is that Wertham had an incredible and laudable career doing things other than making himself a formidable (and infamous) enemy of comic books and thus to generations of children anywhere.

So how is Wetham depicted while he is at perhaps his most noble, in his legitimate work with children's mental health (including examining the effects of segregation and helping to end one of our country's most disgraceful practices)?

Aside from being staggeringly ableist (why yes, that is the mentally ill, including a child suffering from the effects of segregation ((how hilarious!)), depicted as straight-jacketed and twitching, crazed grins on their faces) it comes off as distracting, like the artist was trying to either out-do the writer (narrator) or just lacking in depth (the book didn't trust the reader to stay for the text alone, the illustrations had to be a joke in every panel, whether it distracted from the information trying to be conveyed or not).

Other problems include the book too-frequently stretching too wide a swath to give an idea of the times in which the medium is competing. A considerable portion of the book is dedicated to the animation wars between Walt Disney and Max Fleisher, which, while they are tangentially related to the art of the comic book, don't really have to do with it directly.

The book leaps around unevenly through time and the disconnect between narration and art makes it even more difficult to follow.

The book has its designated heroes, among them Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, and (to no one's surprise) Stan Lee. Understated (although it warrants a few pages) is the incredible impact Art Spiegelman's Maus had on the formation of the "graphic novel" genre (and the legitimization of the "comics" medium with its Pulitzer). And too easily is that section cast as obnoxiously as much of the book. The book quotes Spiegelman's marveling over the success of his choice of medium in which to tell the story of his parents survival of the Holocaust:

The book also plants its creators firmly in a very myopic past. Aside from its late-Boomeresque mistrust of the digital age that ranges from dopey (when discussing the evolution of a theoretical superhero through the decades, he fights WWII in the Golden Age of comics, the cold war in the Silver Age, and presumably al-Qaeda in the "modern" age, but while "Twittering about it on Facebook!") to not-that-accurate (the book postulates "comic book piracy" as on par with piracy of other mediums in frequency-- and all along you probably just thought it was the fact so many authors and artists have a way to freely present their media to the public but without a real sales model!).

But clumsiest of these is the incorrect and, if we want to clean it up, "old-fashioned" (although from the beginning, it's never been actually true) belief that comic book enthusiasts are, like most of their artists and writers, men:

It could be argued that that's an accurate panel; surely the "traditional" comic book store isn't the most welcoming place to women? Okay, but consider the narration versus the panel: why is a female depicted as the "casual" reader? Why are women and girls apparently not considered "geeks" in the "geeks only" atmosphere? You could argue that it's just poorly worded, perhaps; possible, better rewrite: "To the direct market's critics, its struggles are merely chickens coming home to roost-- the inevitable result of abandoning the idea of an inclusive atmosphere in favor of one that caters to a select few."

But the book comes off as (distractingly) dated in other ways. When examining the charges leveled at comic books by foe Doctor Fredric Wertham (who we met above) in his 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent: the Influence of Comic Books on Today's Youth, the book examines the "comics promote homosexual behavior charge" thusly:

Why yes, that's Batman and Robin getting married. Nothing new in the trope that Batman and Robin are not-so-closeted, but you'll notice that Batman is attired in a wedding dress. At the time of the book's publication (this year), several states in this country recognize legal same-sex marriage, with more on the coming ballot. Same-sex couples abound on popular television and popular films. Even popular comic bookss now feature same-sex marriages! (Archie introduced its first openly LGBTQ character in 2011, Kevin Keller, who happened to also be an active duty military officer, and had him marrying his boyfriend the same year, while Marvel Comics introduced openly gay superhero Northstar and his wedding this past year. Even DC Comics has gotten in on the diversity by revamping old characters in a new series including Green Lantern, who now happens to be openly gay.)

So why on earth is a same-sex wedding depicted in this day and age as one of a male couple having to "be the woman", complete with frilly gown and floral bouquet? You might make the argument that the book is trying to tap into the mindset of the period (although I'm pretty sure anti-gay forces in the 1950s didn't actually get so far as legally recognized same-sex marriage in their perceived horrors of homosexuality), save for a likewise obnoxious stereotype paired with the charge that Wonder Woman is actually a lesbian:

The combat boots, the Indigo Girls CD, and even the Seinfeld reference firmly plant (and paint) the accusation as a stereotype at least a decade and a half old. The stereotype isn't even up to date, either now or by a 1950s standard (given the anti-gay propaganda I've seen, a more accurate lesbian stereotype from the '50s might have Wonder Woman depicted in men's clothing and blatantly ignoring a plethora of male suitors whilst openly attempting to seduce unwilling "normal" women, the more attractive the better-- you know, the stereotype of the predatory homosexual "infecting" others with their illness, in this case perfectly good females that are thus being stolen from men).

The book's jumbled and inconsistent timeline makes it not really redeeming as even a primer to adults, let alone for kids, with enough "inappropriate-am-I-making-you-laugh-yet? I'm-so-bored-with-this-illustrating-stuff!" references aside from the various stereotypes we've seen.

The best thing that can be said about this book is the fact it has so much promise in its premise yet is so poorly done it almost begs for a proper execution of the idea.

Notable: In the chapter where the book (frequently inaccurately) considers the current market place under the influence of the internet, "The Oatmeal" creator Matthew Inman gets a mention as finding a successful profit model from his cartoons through merchandise sales (of course there's always the fact that Inman's work isn't really in the same "comic book" medium as put forth here any more than "Dilbert" or "The Far Side", but to be fair, the book is more or less speaking generally of artists' ways of making money from their creations via the internet).