5. beau geste

RADICALISME. D’autant plus dangereux qu’il est latent.

RADICALISM. All the more dangerous when it is latent.

- Gustave Flaubert, Le Dictionnaire des idées reçues[ 0]

Complementing his treatment of mimesis, Erich Auerbach’s 1944 essay “Figura” lays down a classic account of figurative meaning. According to Auerbach, “figura is something real and historical which announces something else which is also real and historical. The relation between the two events is revealed by an accord or similarity.” Thus figurae connect persons and events as symbolic links in a providentially understood historical sequence. Thus the world recounted in the Bible remains imperfectly revealed. Every pivotal historical moment therein is understandable as a figura perpetually pregnant with meaning, yet always resistant to maieutic, the Socratic midwifery that might deliver full figuration a later historical moment. Within such moments history itself, with all its concrete force, remains forever a figure, cloaked, forever inviting and forever requiring the final disclosure, the final demystification, yearned for by the author of the Book of Revelation. As such, figurae are identifiable only in retrospect, when a type, or promise adumbrated or constituted by an earlier event or person is fulfilled or realized by its anti-type, a later event or person. Accordingly, in order to approach an understanding of the figurative meaning of the bad glazier and his bohemian tormentor, we must achieve two tasks. The first is to provide a retrospective account for these characters as realizing a prior historical promise that inheres in the locus classicus. The second is to define their fulfillment by the ensuing turn of historical events that comprises their locus modernus.[ 1]

The responsibility lies with the human heart. As with persuasion, interpretation is inseparable from its underlying desires. The argument of Socrates against rhetoric dirempted from justice weighs in equal force against hermeneutics. Interpretation is to the recipient of communication as persuasion is to its originator. The first order of our endeavor is, therefore, the attainment of total candor:If any ambitious man have a fancy a revolutionize, at one effort, the universal world of human thought, human opinion, and human sentiment, the opportunity is his own-the road to immortal renown lies straight, open, and unencumbered before him. All that he has to do is to write and publish a very little book. Its title should be simple - a few plain words - “My Heart Laid Bare.” But - this little book must be true to its title.

Now, is it not very singular that, with the rabid thirst for notoriety which distinguishes so many of mankind - so many, too, who care not a fig what is thought of them after death, there should not be found one man having sufficient hardihood to write this little book? To write, I say. There are ten thousand men who, if the book were once written, would laugh at the notion of being disturbed by its publication during their life, and who could not even conceive why they should object to its being published after their death. But to write it - there is the rub. No man dare write it. No man ever will dare write it. No man could write it, even if he dared. The paper would shrivel and blaze at every touch of the fiery pen.

As he experimented with prose styles, Charles Baudelaire took up this marginal challenge by Edgar Allan Poe. He seemed compelled to create a readymade masterpiece by daring to write a book with complete honesty. The masterpiece never came to pass. Baudelaire’s literary executors were left with a stack of notes captioned after Poe’s phrases, and My Heart Laid Bare. On one of these pages, the poet recalled his revolutionary past:

Mon ivresse en 1848.

De quelle nature était cette ivresse ? Goût de la vengeance. Plaisir naturel de la démolition. Ivresse littéraire ; souvenir des lectures.

Le 15 mai. - Toujours le goût de la destruction. Goût légitime, si tout ce qui est naturel est légitime.

My intoxication in 1848.

What was the nature of this intoxication? A taste for vengeance. Natural pleasure of demolition. Literary intoxication; memory of readings.

The 15th of May. - Always the taste for destruction. A legitimate taste, if everything that is natural is legitimate.

Les horreurs de Juin. Folie du peuple et folie de la bourgeoisie. Amour naturel du crime.

The horrors of June. Madness of the people and madness of the bourgeoisie. Natural love of crime.

Ma fureur au coup d’État. Combien j’ai essuyé de coups de fusil ! Encore un Bonaparte ! Quelle honte !

Et cependant tout s’est pacifié. Le Président n’a-t-il pas un droit à invoquer ?

Ce qu’est l’Empereur Napoléon III. Ce qu’il vaut. Trouver l’explication de sa nature, et sa providentialité.

My anger at the coup d’État. How many gunshots I mopped up! Another Bonaparte! What a shame!

And yet all is pacified. Has the President no right to invoke?

What is the Emperor Napoléon III. What he is worth. To find the explanation of his nature, and his providentiality.

Être un homme utile m’a paru toujours quelque chose de bien hideux.

1848 ne fut amusant que parce que chacun y faisait des utopies comme des châteaux en Espagne.

1848 ne fut charmant que par l’excès même du ridicule.

Robespierre n’est estimable que parce qu’il a fait quelques belles phrases.

Being a useful man always seemed to me something hideous.

1848 wasn’t amusing but because everyone made up utopias like castles in Spain.

1848 wasn’t charming but through the very excess of ridiculousness.

- Mon cœur mis à nu, V.8, OC.I.679.

- My Heart Laid Bare, translated by MZ

Laying your heart bare is an all-consuming vocation. As old age encroaches upon the cardiac exhibitionist, the greatest challenge of his aging becomes to resist the tendency to don pajamas and bedroom slippers in sullen anticipation of The Big Sleep. Asked to identify his greatest ambition in life, the writer Parvulesco, a dandified descendant of Baudelaire, intoned to his interviewers in Jean-Luc Godard’s À bout de souffle: « Devenir immortel… et puis… mourir. » Baudelaire remains ageless, thanks to his good fortune in dying shortly after tasting the fruit of immortality. Would we hold him in such esteem, were he to recover from his stroke to become an eminent septuagenarian academician, basking in the glory of the fleurs du Mal, a guest of honor at the cutting-edge, yet exceedingly polite lundis of Stéphane Mallarmé? Would he have reveled in the final decade of the 19th century, as France enjoyed economic expansion and political stability, having officially expiated the horrors of the Paris Commune in the Butte Montmartre basilica of Sacré-Cœur, reaching to the lowest of the political tastes of its time through the highest point in the city’s topography? Or would he have jeered at the finances of the Republic, censured its gulling by the Panama scandal, urged its political implosion by the popular success of the anarchist and the socialist movements, or repudiated the glitter of the Banquet Years for its dependence upon popular misery, emphasized by frequent strikes and the growing labor movement? His words afford no answer. But their self-designated inheritors, including some of the spiffiest artistic luminaries of the time, like Stéphane Mallarmé, Camille Pisarro, Octave Mirbeau, Félix Fénéon, and Laurent Tailhade, compounded their fashionable lifestyle of avant-garde icons by affecting a serious commitment to the cause of anarchism.

Anarchism has not fared well in the eyes of historians. Originally a powerful threat to the authoritarian communism in the 1st International, causing its dissolution by Marx, fearful of Bakunin’s popularity, a vital force in the fin de siècle politics, its doctrine seems to have lost all of its relevance in today’s world. Before the birth of anarcho-syndicalism, the very notion of an anarchist party was seen by the faithful as contradicting the spirit of the anarchist movement. From the vantage point of revolutionary success borne out by peerless flexibility in his single-minded pursuit of power, Lenin rightly reproached stiff-necked anarchists of his own time for their lack of concern with the present. But if anarchist action was wracked by squabbles and dissociated from immediate political goals, if the lack of organization and the repudiation of dominion were implicit in the very idea of anarchism, the symbolic power of “propaganda by the deed” belies its dismissive reckoning in the conventionally political terms of democratic suffrage. The specter of anarchism persists in our myriad terrorist enemies, foreign and domestic, as their spectacular deeds propagate through the complicit conduits of mass media. Cataloguing the stale commonplaces of his time in his Le Dictionnaire des idées reçues, Gustave Flaubert recorded a popular resort to the sturdy cudgel of Greek mythology in the service of political animadversions: « Hydre (de l’anarchie). Tâcher de la vaincre. » In serving our endeavour of defeating constantly regenerating adversaries, our clichés are no less strident, if unencumbered with classical learning.

It is the first of May, 1891. Eager for a field test of its newly designed Lebel machine gun, the French Army turns to a peaceful demonstration at Fourmies for its site. The result is 14 dead and 40 wounded. Elsewhere, in an action against a rally at Clichy, three anarchists named Decamps, Dardare, and Léveillé are arrested. At the local police station the constables knock them around in a passage à tabac through a gauntlet of nightsticks and revolver butts. At the trial, prosecutor Bulot demands the death penalty for the defendants. Unmoved by the defense citing the abuse of authority, Judge Benoist sentences two of its victims to the maximum allowable terms of hard labor. The insult is felt by all compagnons; the vengeance is carried out by Ravachol.

An itinerant apprentice into assorted trades turned to murder and grave robbery in the course of his adherence to the cause of workers’ liberation, he takes retribution for the Clichy defendants by bombing the homes of Benoist on the 11th of March, 1892 and that of Bulot on the 27th of March, 1892. During the same month he bombs the Lobau Barracks in Paris in response to the massacre at Fourmies. Ravachol’s dynamite casseroles cause extensive property damage, but no deaths. Their maker is arrested at the restaurant Véry thanks to a tip of the waiter Lhérot, the owner’s brother-in-law, to whom Ravachol had rashly confided his anarchism a few days earlier.

On the 23rd of April, the night before his trial is scheduled to begin, another bomb stops Lhérot in the process of recounting the tale of the fabled anarchist’s arrest to the customers. The chatty waiter escapes unhurt, but the bomb tears to bits the proprietor Véry together with one of his customers. The anarchist press gleefully refers to the bombing as a vérification.

Accepting full responsibility for the earlier bombings, Ravachol appears as the anarchist avenger. In his zeal, he preaches the anarchist gospel to his jailers.

At his trial in Paris, after reciting a litany of popular misery, he announces: Et toutes ces choses se passent au milieu de l’abondance de toutes espèces de produits. On comprendrait que cela ait lieu dans un pays où les produits sont rares, où il y a la famine. Mais en France, où règne l’abondance, où les boucheries sont bondées de viande, les boulangeries de pains, où les vêtements, la chaussure sont entassés dans les magasins, où il y a des logements inoccupés! Comment admettre que tout est bien dans la société, quand le contraire se voit d’une façon aussi claire? Il y a bien des gens qui plaindront toutes ces victimes, mais qui vous diront qu’ils n’y peuvent rien. Que chacun se débrouille comme il peut ! Que peut-il faire celui qui manque du nécessaire en travaillant, s’il vient à chômer ? Il n’a qu’à se laisser mourir de faim. Alors on jettera quelques paroles de pitié sur son cadavre. C’est ce que j’ai voulu laisser à d’autres. J’ai préféré me faire contrebandier, faux monnayeur, voleur, meurtrier et assassin. J’aurais pu mendier : c’est dégradant et lâche et même puni par vos lois qui font un délit de la misère. Si tous les nécessiteux, au lieu d’attendre, prenaient où il y a et par n’importe quel moyen, les satisfaits comprendraient peut-être plus vite qu’il y a danger à vouloir consacrer l’état social actuel, où l’inquiétude est permanente et la vie menacée à chaque instant. And all these things take place amidst plenty of all kinds of products. It would be understandable if it took place in a land where products are scarce, or where there is famine. But in France, where plenitude reigns, where butcher shops are crammed with meat, bakeries with bread, where clothes and shoes are packed into shops, where housing stands vacant! How to admit that all is well in the society, when the opposite is seen so clearly? There are many men who will pity all these victims, but will tell you that they could do nothing about them. Let everyone get by as he can! What could do one who cannot meet his needs while working, if he becomes unemployed? Nothing but let himself die of hunger. Then they will toss some compassionate words upon his carcass. That is what I chose to leave to others. I preferred to make myself into a smuggler, forger, thief, murderer, and assassin. I might have begged: it is degrading and cowardly, and even punished by your laws that make misery into crime. If all the needy, instead of waiting, took wherever things were, by whatever means, the sated might understand faster that there is a danger in wishing to sanction the current social conditions, where anxiety is permanent and life is threatened every moment. On finira sans doute plus vite par comprendre que les anarchistes ont raison lorsqu’ils disent que pour avoir la tranquillité morale et physique, il faut détruire les causes qui engendrnt les crimes et les criminels : ce n’est pas en supprimant celui qui, plutôt que de mourir d’une mort lente par suite de privation qu’il a eues et aurait à supporter, sans espoir de les voir finir, préfère, s’il a un peu d’énergie, prendre violemment ce qui peut lui assurer le bien-être, même au risque de sa mort qui ne peut être qu’un terme à ses souffrances. Doubtless we will end up sooner realizing that the anarchists make sense in saying that to attain moral and physical peace, we must destroy the causes that give rise to crimes and criminals: it is not by suppressing him, who, rather than die a slow death ensuing from hardships that he endured and had to endure, without hope of seeing their end, prefers, if he has a little energy, to take by force that, which can assure his well-being, even at the risk of death that cannot but put an end to his suffering. Voilà pourquoi j’ai commis les actes que l’on me reproche et qui ne sont que la conséquence logique de l’état barbare d’une société qui ne fait qu’augmenter le nombre de ses victimes par la rigueur de ses lois qui sévissent contre les effets sans jamais toucher aux causes; on dit qu’il faut être cruel pour donner la mort à son semblable, mais ceux qui parlent ainsi ne voient pas qu’on ne s’y résout que pour l’éviter soi-même. That is why I have committed the acts for which I am blamed, and which are nothing but logical consequences of the barbarous condition of a society that does nothing but increase the number of its victims through the harshness of its laws that treat the effects with severity without ever reaching the causes; they say that it takes cruelty to give death to his fellow man, but those who say it do not see that one resolves to do so only to avoid it for himself. De même, vous, messieurs les jurés, qui, sans doute, allez me condamner à la peine de mort, parce que vous croirez que c’est une nécessité et que ma disparition sera une satisfaction pour vous qui avez horreur de voir couler le sang humain, mais qui, lorsque vous croirez qu’il sera utile de le verser pour assurer la sécurité de votre existence, n’hésiterez pas plus que moi à le faire, avec cette différence que vous le ferez sans courir aucun danger, tandis que, au contraire, moi j’agissais aux risques et périls de ma liberté et de ma vie. Likewise, you, gentlemen of the jury, who will doubtless condemn me to death, because you will believe that it is necessary, and that my disappearance will be a satisfaction for you, who abhor seeing human blood flow, but who, as long as you will believe it useful to shed it to assure the security of your existence, do not hesitate any more than I have to do so, with this difference, that you will do it without endangering yourself in the least, whereas, I, on the contrary, have acted in risking and endangering my freedom and my life. Be it is for their fear of future retributions, or for their sway by l’Idée future, the Parisian jury spares the life of the accused. Ravachol is condemned to forced labor for life. However, the following month he appears before the court of the Loire. Accused of murder and violation of a grave, he earnestly declares: “If I have killed, it was first, to satisfy my personal needs, and then to aid the anarchist cause, for we work for the people’s happiness.” The provincial court is unmoved by his qualified declaration of altruism. Ravachol receives his death sentence with a cry “Vive l’anarchie!” Marching to the guillotine on the 11th of July, 1892, he shouts the obscene, inflammatory verses of “Père Duchesne”: Si tu veux être heureux,

Nom de Dieu !

Si tu veux être heureux,

Nom de Dieu !

Pends ton propriétaire,

Coup’les curés en deux,

Nom de Dieu !

Fous les églis’par terre,

Sang-Dieu !

Et le bon Dieu dans la merde,

Nom de Dieu !!

Et le bon Dieu dans la merde,

Sang-Dieu !! If you want your happiness,

Goddamn!

If you want your happiness,

Goddamn!

Hang your proprietor,

Hack the priests in half,

Goddamn!

Fuck church into the dirt,

God’s blood!

And good God in the shit,

Goddamn!!

And good God in the shit,

God’s blood!!

Ravachol’s last words are cut short by the blade of the guillotine; the stunned spectactors hear only « Vive la ré… », before the head is separated from the body. The police agent reporting the execution notes smugly that the fabled anarchist seems to have recanted his actions by glorifying the French Republic with his last breath. The anarchist press finds another explanation: surely, its exemplary martyr meant to shout « Vive la révolution ! » The violence goes on unabated. On the 9th of December, 1893, Auguste Vaillant enters the gallery, and throws a homemade bomb on the deputies of l’Assemblée.

After twenty minutes of hysterical frenzy, the speaker announces legislative composure: « Messieurs, la séance continue. » The bomb wounds a number of people, but kills no one. During his trial, Vaillant declares that he had charged it with nails instead of bullets, in order to wound, rather than kill. In spite of this humanitarianism, the terrorist is condemned to death, and receives the sentence with the ritual cry of « Vive l’anarchie ! » For the first time since the beginning of the century, a man who had not killed is condemned to die. Despite numerous pleas for mercy coming from the liberal press, many of them due to the victims of his act, the President of the Republic Sadi Carnot refuses to pardon Vaillant. He dies bravely, crying: « Mort à la société bourgeoise et vive l’anarchie ! »

As Jean Maitron observed, Vaillant neither stole nor killed. In attacking the Parliament discredited by the Panama scandal, he elicited public sympathy. The epitome of his moral support belongs to Laurent Tailhade on the evening after the explosion:

Qu’importent les victimes, si le geste est beau !

Qu’importe la mort de vagues humanités si, par elle, s’affirme l’individu ! What matter the victims, if the gesture is beautiful!

What matters the death of indefinite humans if, through it, the individual asserts himself!The fashionable Symbolist writer half-heartedly protests the attribution of the aphorism. No matter. The question posed three decades earlier by Baudelaire has been transposed by a passel of literary disciples and criminal epigoni, from the domain of pure poetry to the boulevards of the City of Light.

Vaillant is executed on the 5th of February, 1894. A week later, a young intellectual, Émile Henry, avenges the anarchist martyr. Following the explosion of his nail casserole, marmite à clous, in the café Terminus at the gare Saint-Lazare, he vainly tries to escape, firing a revolver at his pursuers.

Once apprehended, unlike Vaillant, Henry acknowledges that his intention was to kill. « Il n’y a pas d’innocents », he declares to the court. No citizen is innocent. The bourgeois electorate must pay with blood for its complicity in the murder of the anarchists and the exploitation of the workers. Undeterred by the threat of a death sentence, Henry maintains his composure at trial, as recounted by Jean Maitron: À l’audience de la cour d’assises, il eut de cinglantes répliques :

Le président de la cour d’assises. - Vous avez tendu cette main (…) que nous voyons aujourd’hui couverte de sang.

Émile Henry. - Mes mains sont couvertes de sang, comme votre robe rouge.

Au jury, il lut une déclaration dont voici des extraits : At the hearing of the court of assizes, he lashed out with retorts:

The president of the court of assizes. - You have held out this hand (…) that we see today covered with blood.

Émile Henry. - My hands are covered with blood, like your red robe.

To the jury, he read a declaration excerpted herewith:

« Je suis anarchiste depuis peu de temps. Ce n’est guère que vers le milieu de l’année 1891 que je me suis lancé dans le movement révolutionnaire. Auparavant, j’avais vécu dans les milieux entièrement imbus de la morale actuelle. J’avais été habitué à respecter et même à aimer les principes de Patrie, de Famille, d’Autorité et de Propriété.

“I have been an anarchist for a short time. Not until the middle of 1891 have I thrown myself into the revolutionary movement. Before that, I had lived in the circles utterly permeated by conventional morality. I had been accustomed to respect, and even to love, the principles of Homeland, Family, Authority, and Property.

Mais les éducateurs de la génération actuelle oublient trop fréquemment une chose, c’est que la vie, avec ses luttes et ses déboires, avec ses injustices et ses iniquités, se charge bien, l’indiscrète, de dessiller les yeux des ignorants et de les ouvrir à la réalité. C’est ce qui m’arriva, comme il arrive à tous. On m’avait dit que cette vie était facile et largement ouverte aux intelligents et aux énergiques, et l’expérience me montra que seuls les cyniques et rampants peuvent se faire bonne place au banquet.

But the educators of our generation forget all too often one thing, which is that life, with its struggles and its spoilages, with its injustices and its iniquities, indiscreetly occupies herself with opening the eyes of the ignorant and turning them to reality. That is what happened to me, as it happens to all. They had said to me that this life was easy and largely open to the intelligent and the energetic, and experience showed me that only the cynics and sycophants can secure a good seat at its banquet.

On m’avait dit que les institutions sociales étaient basées sur la justice et l’égalité, et je ne constatais autour de moi que mensonges et fourberies. Chaque jour m’enlevait une illusion. Partout où j’allais, j’étais témoin des mêmes douleurs chez les uns, des mêmes jouissances chez les autres. Je ne tardais pas à comprendre que les grands mots qu’on m’avait appris à vénérer : Honneur, Dévouement, Devoir, n’étaient qu’un masque voilant les plus honteuses turpitudes.

They had said to me that social institutions were founded in justice and equality, and I saw nothing around me but lies and treachery. Each day relieved me of an illusion. Everywhere I went, I witnessed the same sorrows in the ones, the same joys in the others. I was not long in understanding that the lofty words that I had been taught to cherish, Honor, Devotion, Duty, were nothing but a mask concealing the most shameful turpitudes.

L’usinier qui édifiait une fortune colossale sur le travail de ses ouvriers, qui, eux, manquaient de tout, était un monsieur honnête. Le député, le ministre dont les mains étaient toujours ouvertes aux pots-de-vin, étaient dévoués au bien public. L’officier qui expérimentait le fusil nouveau modèle sur des enfants de sept ans avait bien fait son devoir, et, en plein parlement, le président du Conseil lui adressait ses félicitations. Tout ce que je vis me révolta, et mon esprit s’attacha à la critique de l’organisation sociale. Cette critique a été trop souvent faite pour que je la recommence. Il me suffira de dire que je devins l’ennemi d’une société que je jugeais criminelle.

The factory owner who erected a colossal fortune upon the labor of his workers, who lacked all, was an honest gentleman. The deputy, the minister whose hands were always open to bribes, were devoted to the public welfare. The officer who tested his new model of rifle on seven year-old children had done his duty well, and before the entire Parliament, the president of the Counsil offered him his congratulations. All that I saw revolted me, and my mind turned towards social critique. This critique has been put forth too many times to bear my repetition. Suffice it to say that I became the enemy of society that I judged criminal.

Un moment attiré par le socialisme, je ne tardais pas à m’éloigner de ce parti. J’avais trop d’amour de la liberté, trop de respect de l’initiative individuelle, trop de répugnance à l’incorporation, pour prendre un numéro dans l’armée matriculée du quatrième État. D’ailleurs, je vis qu’au fond le socialisme ne change rien à l’ordre actuel. Il maintient le principe autoritaire, et ce principe, malgré ce qu’en peuvent dire de prétendus libres penseurs, n’est qu’un vieux reste de la foi en une puissance supérieure.

Momentarily attracted by socialism, I did not delay my withdrawal from that party. I had too much love for liberty, too much respect for individual initiative, too much repugnance for incorporation, to take a number in the regimented army of the Fourth Estate. Besides, I saw that deep down, socialism changes nothing in the existing order. It maintains the authoritarian principle, and that principle, despite all that might say the alleged freethinkers, is nothing but an old remnant of faith in supreme power.

(…) Dans cette guerre sans pitié que nous avons déclarée à la bourgeoisie, nous ne demandons aucune pitié. Nous donnons la mort et nous devons la subir. C’est pourquoi j’attends votre verdict avec indifférence. Je sais que ma tête ne sera pas la dernière que vous couperez (…) Vous ajouterez d’autres noms à la liste sanglante de nos morts.

(…) In this merciless war that we have declared upon the bourgeoisie, we ask for no mercy. We give death, we must suffer it. Thus it is with indifference that I await your verdict. I know that my head will not be the last one that you cut. (…) You will add other names to your bloody list of our dead.

Pendus à Chicago, décapités en Allemagne, garrottés à Xérès, fusillés à Barcelone, guillotinés à Montbrison et à Paris, nos morts sont nombreux; mais vous n’avez pas pu détruire l’Anarchie. Ses racines sont profondes : elle est née au sein d’une société pourrie qui s’affaisse; elle est une réaction violente contre l’ordre établi; elle représente les aspirations d’égalité et de liberté qui viennent battre en brèche l’autoritarisme actuel. Elle est partout. C’est ce qui la rend indomptable, et elle finira par vous vaincre et par vous tuer. »

Hanged in Chicago, decapitated in Germany, garroted in Jerez, shot in Barcelona, guillotined in Montbrison and in Paris, our dead are numerous; but you will never destroy Anarchy. Her roots are deep: she is born at the sagging breast of a rotten society; she is a violent reaction against the established order; she represents the aspirations of equality and liberty that come to battle in the breach of the present authoritarianism. She is everywhere. That is what makes her untameable, and she will end by defeating and killing you.”

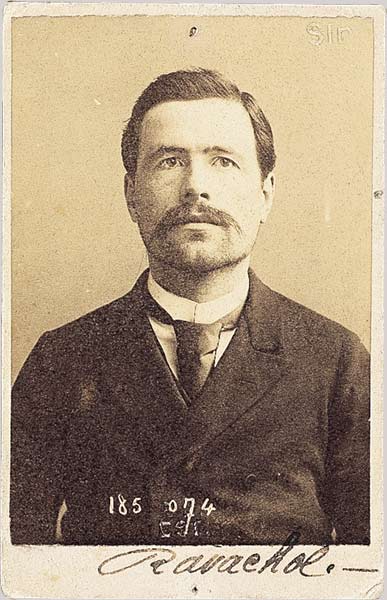

Anthropometric portrait of Émile Henry

Musée de la Préfecture de police, Paris, France / Archives Charmet Henry is executed on the 21st of May, 1894. The last words of the twenty-one year-old poet make the traditional valediction: “Vive l’anarchie!” But this time, the anarchist intellectuals no longer agree on the merits of the act. On the day following the crime, Octave Mirbeau writes: “A mortal enemy of anarchy couldn’t have done better than this Émile Henry, when he threw his inexplicable bomb in the midst of peaceful and anonymous people, who came to the café to drink a beer before going to bed… (one suspects a police provocation).” Félix Fénéon, art critic and friend of Émile Henry, shares the uncompromising belief that the public, as the electorate, is at least as guilty as the politicians it put in place. So he continues his friend’s cause by depositing a bomb disguised as a flowerpot, with the fuse concealed inside a hyacinth stalk, at the restaurant Foyot. No one is killed, but Tailhade, who has risen gallantly to protect his lady friend, loses an eye.

Writing in La Revue blanche, Symbolist critic Gustave Kahn pinpoints the paradox of bourgeois fascination with anarchist violence: “Minos and Pandora, working a priori, became persuaded through the course of their permanence at the pharmacy, that the bomb was a self-bomb, that only Tailhade the anarchist could have placed so fittingly a bomb that was to blow up Tailhade the peaceful diner.” (« Minos et Pandore, travaillant a priori, s’étaient persuadés, pendant le trajet de leur permanence à la pharmacie, que la bombe était une auto-bombe, que seul Tailhade anarchiste avait pu placer si à propos une bombe qui devait faire sauter Tailhade dîneur paisible. ») But Tailhade bears his loss gracefully. He continues to defend the anarchist cause, occasionally making a gesture of taking out his glass eye, and dedicating it to anarchism.

The authorities are not amused. Fénéon, Matha, Jean Grave, Sébastien Faure, and other anarchists are arrested. In the Procès de Trente, the government attempts to subsume the intellectual theoreticians of anarchy along with anarchist terrorists under a common accusation based on the new lois scélérates, broadly prohibiting any associations of malfeasants. Even though it follows the assasination of Sadi Carnot by an anarchist Santo Caserio, the Trial of the Thirty ends with a monumental failure for the prosecution, thanks largely to the ironic composure of Félix Fénéon.

Paul Signac

Sur l’émail, d’un fond rythmique de mesures et d’angles, de tons et de teintes, portrait de m. Félix Fénéon en 1890

Against the Enamel of a Background Rhythmic with Beats and Angles, Tones and Tints, Portrait of Mr Félix Fénéon in 1890.

Oil on canvas, 73.5x92.5 cm, The Museum of Modern Art, New York The presiding judge asks the defendant to explain the presence of detonators in his office at the Ministry of War: - Mon père les avait ramassés dans la rue.

- Comment expliquez-vous qu’on trouve des détonateurs dans la rue?

- Le juge d’instruction m’a demandé pourquoi je ne les avais pas jetés par la fenêtre au lieu de les emporter au ministère. Vous voyez que l’on peut trouver des détonateurs dans la rue.

- Mais pourquoi déteniez-vous aussi du mercure? Vous ne pouvez ignorer que le mercure sert à fabriquer un dangereux explosif, le fulminate de mercure.

- Oui, mais il sert aussi à confectionner les baromètres.- My father had found them in the street.

- How do you explain that one may find detonators in the street?

- At the preliminary hearings, the judge asked me why I hadn’t thrown them out of my window instead of carrying them to the ministry. So you see that one can find detonators in the street.

- But why did you also keep mercury? You can’t be unaware that mercury is used to fabricate a dangerous explosive, the fulminate of mercury.

- Yes, but it is also used to make barometers. A package is brought to the general prosecutor. Gingerly, he opens it. Shit takes place of the expected bomb. The court is adjourned to give the representative of the state an opportunity to clean it off himself. Whereupon Fénéon declares to the general amusement: - Depuis Ponce Pilate, pas un magistrat ne s’était lavé les mains avec tant de l’ostentation!- Since Pontius Pilate, not a single magistrate had washed his hands with so much ostentation! The flameout of anarchist propaganda by the deed came to an abrupt end.with the acquittal of the anarchists at the Trial of the Thirty, and the contemporary introduction of the draconian lois scélérates. Yet the apparent senselessness and futility of these acts need not enjoin us from seeking meanings and lessons in the tragic burlesque of a Ravachol, the rational absurdity of an Émile Henry, and the stoic condescension of a Félix Fénéon. A direct lineage connects, both genealogically and ideologically, the provocation of the prose poems, and the brutal social critique of the dynamiters of the Banquet Years. From the dramatis personae, intimately associated with the key figures of the Symbolist movement and the artistic heirs of Baudelaire, through the paradoxical utility calculation of Laurent Tailhade, to the little flowerpot of the Parisian dandy breaching through the petit bourgeois complacency, and simultaneously outraging and amusing his audience, the spectacle suits the same purpose as the shattering of the windowpanes. The imitation of art by life suggests the fulfillment of the symbolic violence of the prose poems, by the real violence of the anarchist attentats. Our task is to discover the extent, to which the political message of the anti-type was already implicit in the antecedent type.

The reasoning in each instance is open in form, differing from a classical interrogatio in its lack of foregoing argument that leads the audience to an obvious answer to the question posed by the speaker. However, it would be fatal to dismiss Taillhade’s question, resonating through innumerable instances of explosive self-affirmation, as a sociopathic affectation. Hard cases make bad law, nowhere more so than in the case of laws enacted in response to the hard cases of individual terror. But failing to engage their questions leaves us unprepared for confronting forms of life based on taking every thought to its logical conclusion. Rupert Pupkin, The King of Comedy, might have said it best in Martin Scorsese’s parodic context: “Better to be king for a night than a schmuck for a lifetime.”

By kidnapping a popular talk show host at the point of a toy gun, for the sake of a ten-minute guest spot on his top-rated program, the King of Comedy shows himself to have absorbed and subverted the utilitarian ethos: “A guy can get anything he wants as long as he pays the price. What’s wrong with that? Stranger things have happened.” By Rupert’s reasoning, as borne out by historical precedent, no threat of punishment could deter a sufficiently intense and memorable crime. Time and again, contemplative poetic dreamers such as Émile Henry and Félix Fénéon, show themselves capable of mustering the energy to shatter the crystal palace, which might have been secure from assault by a man of action. To this day, the media image of a typical terrorist is that of a sensitive and well-educated young man resolutely averse to the bourgeois trappings of la vie en beau.

The same trappings are repudiated in the Baudelairian succession by René Daumal:

Je préfère lui voir garder cette dure loi, palpable dans le ton de ses phrases, qui le défend de tout compromis. Il est sûr aussi ainsi de ne pas sacrifier à ces idoles modernes : science discursive, morale, progrès, bonheur de l’humanité, autonomie de l’individu, la vie en beau, tout ce fer et ce granit absurde qui pèse sur nos poitrines.I prefer to see him guard this hard law, palpable in the pitch of his phrases, which forbid to him all compromise. Thus he is certain not to sacrifice to these modern idols: discursive science, morality, progress, happiness of mankind, autonomy of the individual, beautiful life, all that absurd iron and granite that weigh down our chests. Taking anarchist doctrine to a logical conclusion, Daumal’s repudiation extends to its organizing principle of individual autonomy. Our remaining task is to uncover the iron and granite rationale behind these manifestations of the destructive urge.

Gustave Courbet, P.-J. Proudhon in 1853, 1865-67

Oil on canvas, 147x198cm, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Villle de Paris

Footnotes

[ 0] Gustave Flaubert, Œuvres, édition établie et annotée par A. Thibaudet et R. Dumesnil, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, Paris : Gallimard, 1951, vol. II, p. 1021.

[ 1] See Erich Auerbach, Scenes From the Drama of European Literature, University of Minnesota Press, 1985. A useful political application of Auerbach’s analysis is found in Vassilis Lambropoulos, The Rise of Eurocentrism, Princeton University Press, 1992. Our principal typological hypothesis identifies the locus classicus in the type of Socrates, locating the locus modernus in the anti-type of Charles Baudelaire. An adequate account of their connection rests on the history of rational desire from its roots in the classical antiquity to its flowering in the revolutionary utopianism of 1848 and its ongoing recapitulation in secular and religious propaganda by the deed.

[ 2] Edgar Allan Poe, Marginalia, Graham’s Magazine, January, 1848, reprinted in Essays and Reviews, The Library of America, 1984, p. 1423.