(no subject)

THE SECRET PROJECT I HAVE BEEN PROMISING ALL SUMMER IS FINALLY DONE.

Homg. I now do not know what to do with myself, my life has no meaning, blah blah blah. Anyway.

1. linnpuzzle and I teamed up.

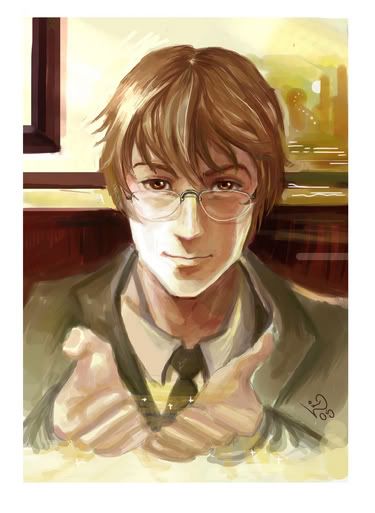

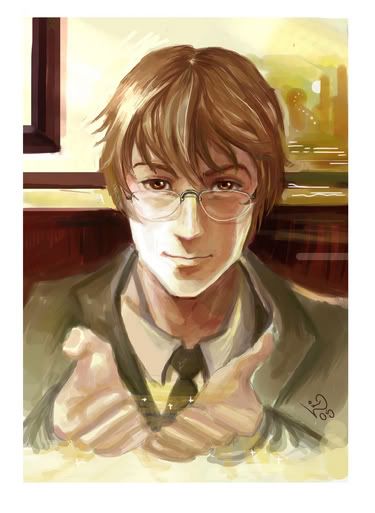

2. There is this story. It is an AU fic in which Remus and Sirius are muggles and meet on a train and Remus is, in fact, a school teacher and Sirius is, like, an investment banker, and then, you know, it all goes downhill from there.

3. There are trains, Kipling, Wales, marking papers, and all sorts of other fascinating things.

4. THERE IS FANTASTIC, GENIUS, BEAUTIFUL ART from the hero of the world at large, Linn. Homg.

5. This fic was originally for sheafrotherdon's dissertation, but has not been posted anywhere other than her community, so it's like A BRAND NEW FIC. A long one, too.

6. Also, yes, the last pic may be colored. Linn's working on it. :X

Without further ado: Remus/Sirius, NC-17, AU, and, uh. Onward, soldiers.

Beware of not-incredibly-worksafe art, towards the end there. Like this is going to discourage anyone.

For girlsclub, with love, because you lot keep me going, especially yeats, imochan, and sheafrotherdon. (Also, hostile_21, but she's off in Tahoe, so to hell with her.)

The Moon's Significant Tremble

Sirius Black isn’t used to people sitting beside him on trains.

It’s four days past Christmas, edging into the desolate grey of the time just past the holidays when everything blends together into long nights and too much shovelling, and he’s coming back from Wales. Sirius has never been entirely sure what one does in Wales, but he goes twice a year, like clockwork, because it seems the sort of thing one ought to do, like sending Christmas cards and giving a few pounds to the heroin addict sleeping in the bus stop. It doesn’t matter that there’s nothing in Wales, just like it doesn’t matter that the Christmas cards will doubtlessly rest on the mantle for a few days before they’re thrown away, like no one bothers to care that the money will only go for more drugs, not a hot cup of coffee and a sandwich.

Sirius has a list of things he’d like to do, which always seem to fall into the no man’s land of his To Do List, lost in the perpetual haze of “when I get around to it.” They’re caught in the January of the bulletin board that hangs in his kitchen, with sprawled phone numbers. The scrap of paper that says Groceries! and the one that says Library books due - Thursday 3:00 PM are lucky, tangible like May, no easier to ignore than the first of the crocuses. They’re always taken care of, again and again, and sometimes Sirius thinks he ought to make a list and work his way down it. He’d like to live in an ideal world where the ultimate goal of visiting Nepal has equal weight in time to remembering to pick up his dry cleaning. He’d like the idea of not going to Wales to be as obtainable as buying laundry detergent, like to remember to carry a flask of coffee and sandwiches in the bottom of his briefcase, to give the man at the bus station something useful.

He’s twenty-six and floundering when he steps into the carriage, with thirty around the corner of the luggage rack and thirty-five in the chewing gum spots under the seats.

Then someone beside him asks to sit down.

He’s half here and half there, tugged two ways by the swish-swish-thunk lullaby of the train, unable to collect his thoughts. Brown eyes, he thinks, then, with the disconnection borne of sleeplessness and the sort of train that hugs the black curves of the hillsides - Kind.

“Sorry?” he says.

The man has a folded newspaper and glasses that slide down his nose. The elbows of his coat are patched, so threadbare that the coat itself seems to have gone beyond beloved into see-through, and he has the same quality - Sirius looks at him for a moment, feeling as if he’s looking through him instead of at him, even when he squints to focus.

“Do you mind if I sit here?” the man repeats, fingers tightening then releasing on the clasp of his bag.

The train is nearly empty, and Sirius wonders - he’s met a few too many of this type, in London. If he sleeps, he’ll wake up to find things missing. But the man’s shirt is clean and his trousers are pressed into starched perfection. There’s no wedding ring, but his watch is decent; too plain to be stolen, too expensive to signify desperation. It’s a few hours back to London, and Sirius doesn’t particularly want to spend those hours looking out the window into the inky blackness of England at night. His briefcase has a lock.

“Not at all,” he replies, finally, the right thing to do, and moves his bag.

The answering smile is almost enough to convince him. “Lupin,” the man says, extending a hand. “Pleasure.”

“Sirius Black,” he answers, and notes that the handshake is firm.

It’s surprisingly easy conversation, with the fluid quality that comes of talking to strangers. The holidays are a peace accord, an unsung grace - there is a slow, warm kinship between all of humanity, the dull roaring silence of the city at night, with the windows open. It’s being alone but unafraid, lying in the dark just before sleep comes, and knowing that beneath the dull hum of car tires through raindrops, there is the steady, even breathing of a thousand other people.

It’s impossible to be lonely in London, like being a single cell in a slowly waking organism, some rough beast slouching towards Bethlehem, but here, in the middle of nowhere on an almost-empty train, it’s expected, and therefore, a small point of wonder when his expectations fail.

Lupin talks with his hands - slow, expressive motions that captivate and hold tight. They’re strong, Sirius thinks, absently, as Lupin talks of India: a cupped gesture to indicate the Ganges, the indelicate curl of his fingers to show the slow slide of a mango down one’s throat. The hands of someone unafraid to work.

Sirius has always wanted hands like that. His own are pale, and the only calluses are those of pens, subtle nicks from thick paper, a broad scar across his palm; a cut from a kitchen knife as a boy, nearly through the tendon. He keeps them still and steady, balanced against the back of the seat in front of him, kept safely in his lap. Touch is an anchor, a lifeline. The man beside him trusts the tilting planet enough to let go; Sirius does not.

“With consideration to the constraints,” Lupin is saying, when Sirius surfaces from the warm lull of his voice, “I believe it’s possible.”

Venice, Sirius thinks, he’s talking of floodgates in Venice, but it only brings the knowledge of somewhere else Lupin’s hands have been. He wonders if his touch might be electric, enough to jolt him from here and the endless tedium of life, if their handshake has changed him on indiscernible levels.

He wonders if you can think that of someone you’ve met on a train, wonders, in the slow, dull heat of the carriage, pulled towards sleep by the reassuring sound of a deep voice, the half-sway of the train, if the broad, worn pads of Remus’s fingers feel warm, like he imagines the Venetian canals might.

“I wish,” he murmurs, too lost to follow the conversation, feeling the stray-electron hit of neurons firing, nothing to do with this, “I knew what India tasted like.”

There’s a long, startled half-blink from Lupin, as if Sirius has caught all of him off guard with the question, instead of just his mind and mouth.

“Like curry,” he says, finally, after a long pause, with a warm, quiet smile that Sirius feels complete the circuit. “Like curry, and like rain.”

He failed chemistry, can’t remember the laws of biology, but this, he thinks, this, he knows, is what they meant, all along -

He needs to know this man.

When he falls asleep around midnight, Lupin is still talking, voice low and lilting. The dull hiss of air through compartment doors and the slow footsteps of the conductor are all the lullaby he needs; he wakes to the gentle press of fingers against his shoulder.

“Nearly there,” Lupin murmurs, with a smile that makes his stomach flip over, like the prospect of sex or unsettling news, the dull-steady tempo between action and reaction, tension and release.

“Sorry,” he mumbles, still tired, disoriented, the lights of London flashing by in the darkness, pinpricks of white amidst the January black. “I must have been more tired than I thought.”

“Not a problem,” Lupin replies, then gestures to the book at Sirius’s feet, the one he’s forgotten he had - “Kipling. No one much reads Kipling anymore.”

Sirius somehow doesn’t want to admit that he doesn’t particularly like it - too dark in the heart of things, too tense, as if the pages are too thin for all they hold. “I’ve only started,” he says, instead - not a lie, if three-quarters through is beginning.

“Beautiful prose,” Lupin murmurs. “May I?”

Sirius passes over the book, and Lupin pulls a pen from his jacket pocket, tarnished but delicate, probably an heirloom. “Do you mind?” he says, and Sirius shakes his head.

He writes his name on the inside cover, just behind the dust jacket, against the edge, Remus Lupin, and Sirius thinks it’s an oddly fitting first name, longs to see how it tastes, but can’t quite bring himself to - and then, his number underneath, small and perfect, in the penmanship of someone who has never forgotten grade school lessons.

“I rather enjoyed the discussion,” he says, finally, with another stomach-twisting smile. “If you wanted to ring, sometime - ”

“I’d like that,” Sirius replies, and wonders if this is what friendship is like when you care about what the other person thinks, this half-caught flutter in your chest, the imperceptible tightening of stomach muscles, like asking someone to dinner or speaking to an author at a book signing.

Remus stands, collecting his sole, lonely piece of luggage as the train slides to a stop, and Sirius loses sight of him in the dim, two-am-shadows of the train station, all florescent lights and washed-out faces, people whose only desire is to be somewhere, not caught in the limbo of faded travelers and the dull buzz of lights, with the puddle of water just inside the doors, the dull roar of taxis outside on the street.

It’s only when he gets home, into the open arms of a dark, empty flat, with the mail piled inside the door and no milk in the fridge, that he realizes he’s left his book on the train, in Remus Lupin’s seat, and try as he might, he can’t recall the crisp, sharp numbers left on it.

He falls into his own bed, made deeply unfamiliar by just a few days away, and thinks that he’ll call in the morning, too tired to consign Remus Lupin to temporary life as a note on his bulletin board.

He remembers, somehow, when he wakes, and in the woolen-dark of another January morning, he calls the train station, which says they’ll watch for his book but fail to take his number. He tries directory assistance, but the number is unlisted, and he tries to tell himself the low pang in his chest is absurd, that the loss of a stranger on a train is hardly worth thinking twice over.

He didn’t like the book anyway.

He forgets.

It’s almost a month later the next time he’s on a train, Valentine’s Day, with low, bitter edges and quiet regret. He’s coming back from visiting his mother - the institution in the countryside, so tragic for a mind to go at such a young age - and the creeping edges of loneliness are like the frost that builds against the windowpane; all right if avoided, too hard-broken cold to touch.

He stares out the window into the dark until the attendant comes by with the cart, and they’re almost the only people on the train. He turns to look at her for a long moment and the slow reflection of this is there; she’s working too late on a holiday to be anything but alone, he’s on a midnight train from nowhere.

“Going home to someone?” she says, with false brightness, shadows underneath like edges of layered paper, over and over again, and her eyes are too old for the youth of her face.

“Unfortunately not,” he murmurs, with a tight, quiet smile, and here, he knows, it is again, the slow, familiar stomach flip at her half smile of sympathy, of kinship.

He could have someone warm in his bed tonight, and she’s pretty, with dark eyes and small breasts that he can catch the edges of through her uniform, too cold in here for the short sleeves she wears. Let me give you my coat, he could say, you look cold, and then she might sit beside him, later, and in the slow, smudged blinks between now and four in the morning he might not be so alone. He can imagine, in half a second, what her breasts could feel like cupped in his hands, how her pulse might beat beneath his mouth, sweet and rapid in the hollow of her throat, how she might feel around him, warm and slow and oh god there.

He doesn’t want it.

“Coffee, please,” he says, quietly, and doesn’t let his fingers touch hers as he hands over the money.

It isn’t until he’s halfway home on the underground that he realizes he’s left his keys on the train, but London’s the last stop of the night, and he thinks that perhaps he can catch the cleaners before a locksmith becomes necessary.

They direct him to a room of lost and found items, and he finds his keys on a low shelf, lost amongst the mittens and gloves of a never-ending season. When he stands, he catches sight of a familiar dust jacket peeking out from a faded purple jumper, and slow, unsteady hands pull it out again, memory too tangible to have really been erased.

Understanding, he thinks, and as he unfolds the cover, there it is - ink unfaded, letters as crisp as the day they were written.

Remus Lupin, and a slow, clear column of numbers.

He tucks the book inside his jacket, close to his heart, and goes home.

He rings the next morning - too early, with the sun just coming in over the snow that covers the windowsill, dyeing it orange, and listens to the slow click of the connections, the dull, tin-coated ring. Someone picks up, and he can hear sleepy breathing, distorted by the bad connection that comes from calling the wrong part of town, where no one much gives a damn about phone connections.

“Hello?” the voice comes through, recognizable even through static, and Sirius thinks, for a moment, that he ought to have planned out what to say, because he’s close to saying everything he’s ever needed to say to a stranger he’s met once, on a train, in the middle of the night. I’m lonely, he nearly says. I’m afraid of staying like this for the rest of my life. He wonders if he’s turning into his mother, hearing voices in his head.

“It’s Sirius,” he says, finally. “Sirius Black, from the train.”

There’s a dull hum of recognition, but the voice on the other line doesn’t say all the things Sirius expects it to, such as why are you calling at half six or I’m afraid I don’t remember. Instead, it surprises him. “What are you doing this afternoon?”

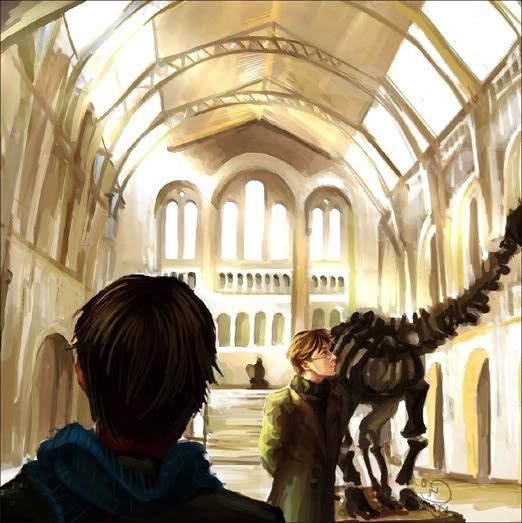

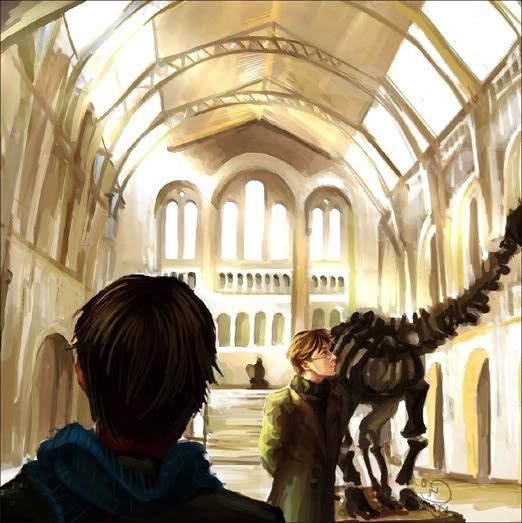

Remus is taking a group of his students - somehow, the fact that he’s a professor feels right to Sirius; teach me, he wants to tell him - to the Natural History Museum, and he wonders if they might meet after. Admission is free, it’s warmer than the street (said ruefully, as if there’s first-hand knowledge to back it), and perhaps they might have something to eat, after.

“Yes,” Sirius says, instantly, firmly, and looks forward to getting off work for the first time in longer than he can remember.

The next time he sees him, it’s half four, and he’s standing in the Central Hall beneath the skeleton of something large and imposing, all arches and angles, the late-afternoon sunlight spilling in from cathedral windows onto him, lighting him gold.

Sirius waits a moment, just watching, as the crowds spill around him, schoolchildren with bags from the gift shop, women in knee-length woolen coats, a man pacing back and forth, back and forth, across the length of the thing.

Lupin stands still, eyes half-closed, gilded in light and the dust moats of a thousand footsteps, steady with obvious reverence for this something. Sirius has always simply walked by, hardly even noticing the hulking statue, in a hurry to get to things more glamorous; the gallery of jewels, the human remains. Here, though, he can see the slow curve of age set in stone, the butterfly-wing fragility of this. He understands, for half a moment, what it is to be here, in this moment, and he finds it strange that he feels alive for the first time in months standing in the hall of a museum he’s never really enjoyed, watching a stranger enjoy a skeleton.

“Lupin,” he says, finally, stepping across the stone to stand in the sun behind him.

“Beautiful, isn’t it,” he replies, not looking away from the dinosaur.

“No,” Sirius murmurs, honestly. “But it’s worth looking at.”

Lupin smiles. “It is indeed. My students rush by, but I believe it’s my favorite part of the museum.”

“Mine too,” Sirius says, and is almost surprised to find he isn’t lying.

Dinner is a small, nearly empty Indian restaurant a few blocks down. It’s not luxurious, but it’s warm, and the food is cooked as they wait. “I’m sure you’re used to better,” Lupin says, in the tone of someone too familiar with poverty to be ashamed, anymore, “but teaching isn’t exactly a high-end profession.”

“Don’t be daft,” Sirius says, finally, even if he is. The flicker of a dim light across Remus’s face is enough to make up for the plastic serving ware, and to his surprise, the food is better than most restaurants he’s been to.

He’s not sure where the evening goes, but the next time he looks at his watch, it’s nearly eight and he’s on his fourth cup of coffee. “I don’t live far from here,” Lupin says.

“I’ll walk you home,” Sirius replies.

The cold is biting, even in the city, but the company is enough to keep him warm - easy banter back and forth about the book Sirius read a week ago, the most recent political scandal. Lupin climbs the stairs to a door, turns three different keys in three different locks. “Too cold for trouble,” he says, with a smile. “But I’d take a cab home.”

“Goodnight, Lupin,” he replies, gloved hands stuffed in his pockets against the cold.

Lupin half-turns, door already open. “Remus,” he says, finally. “It’s Remus.”

“Remus,” Sirius whispers, as he closes the door behind him, and it feels exactly like he imagined it would, in his mouth.

The next month slides by in the slow inevitability of phone calls - some in the middle of the night - and movies - foreign and drama; they can’t agree on anything else. Sirius thinks, both, that he has never known someone so well and that he has never known someone so little.

This is someone who he can call at half four in the morning when he can’t sleep, and, worse still, can’t get the last block of the crossword. Remus, he discovers, makes better coffee than anyone else in England, and sometimes, in an act that Sirius doesn’t understand, he comes to mark papers at Sirius’s kitchen table while Sirius watches BBC or tries to read.

He only goes to Remus’s flat twice. The first time, he merely steps in while waiting for him to get his coat, wary of tracking London snow on the entryway carpet. The walls are the white that signifies ownership by someone who can’t afford not to get his security deposit back, and trains rattle by at all hours of the night, so Remus can’t hang things on walls. There’s not enough hot water, Remus says, and the pipes tend to freeze in winter - the second time Sirius is there, he’s helping to fix one - but it’s close enough to the school that he can walk, even in winter, and the rent’s low enough that he can put a little away.

It’s the proximity to school, though, Sirius knows, that makes Remus tolerate the faulty wiring and leaky windows. He sees him teach only once, but there’s enough passion in Lupin’s voice to make Sirius wish that he’d had a teacher such as Remus Lupin. If he had, he thinks, he wouldn’t be where he is today. For the first time in years, however, he entertains the possibility that where he is could be something close to all right.

He isn’t sure what he’s doing - isn’t sure if this is how things are supposed to be or if this is strange, if everything before this has been right and this is wrong, or if it’s the other way around. He knows that he doesn’t lose much sleep at night, anymore, and that being alone doesn’t hold quite so much agony, but he worries, sometimes, that it’s dangerous, to place all one’s faith in one person, if it’s acceptable for a man to love another man as he loves Remus.

It’s like falling, slow and unsteady, with water and out held hands to break your fall. Doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt when you hit, he thinks, the only time the analogy occurs to him, but wariness is not enough to prevent trust.

He only sleeps with one woman in the first two months he knows Remus. She’s tall and just the right shade of off-color brunette, quiet and well-spoken. She talks with her hands.

It’s not bad - Sirius doesn’t think he’s so far gone that sex could be bad, not like this - but when she rolls out of bed in the morning and takes one of his shirts with her, he doesn’t bother to call again. A bed that felt of another person used to be a comfort, but he washes the sheets twice and gives away the jumper she leaves on his sofa.

Things are comfortable again, after that - nothing just under his skin, taut and irritating - and then, just as quickly, they’re strange once more.

He’s helping Remus pull weeds around the crocuses in his small scrap of flowerbed, dirt under his nails, cheeks flushed from the cold spring wind.

“What are we doing?” Remus murmurs, finally, looking at Sirius’s hands, then his own, then the purple and yellow flowers between them.

“Pulling up weeds,” Sirius answers, without really thinking about it, and then he’s acutely aware that Remus is watching him, with the same scrutiny he applies to things he thinks are beautiful - dinosaur skeletons and small flowers and an exceptionally well-written paper.

“Not that,” Remus says, softly, and leans back on his heels.

Sirius puts his trowel down slowly, heart in his throat, where he can feel it - thud thud thud. “I don’t know,” he says, watching the slow, thoughtful curl of Remus’s fingers in his lap, against faded blue jeans and the hem of an old cotton jumper.

Red is a bad color on him, Sirius thinks, absently, and he thinks perhaps this isn’t the sort of thing you ought to be thinking of, when you’re leaning in, like this. He thinks this might be another science lesson - gravity, this time around, elemental forces, but then the thud of his own blood in his head drowns out everything, and he doesn’t think at all.

It might be nothing, this pull, might be the attraction of a lost eyelash on his cheekbone, to be brushed away with a thumb, might be the magnetic pull of the sun in Remus’s eyes or the tidal tug of a smudge of dirt on his nose.

But Remus lifts a hand, there, to curl against his jaw, thumb just brushing against the corner of his mouth, eyes shuttered and unreadable, and this, Sirius knows, is the very definition of in too deep, because you can’t step back from the look in his eyes.

Maybe, he thinks, this isn’t what I think -

Then Remus leans in and kisses him, in full view of all of London, and all Sirius can see is his face and the electric blue spring sky behind. It’s just the press of mouth to mouth, nothing that ought to be amazing, and he’s done it four thousand times before. It’s not amazing, he thinks, almost disappointed in something that he thinks ought to be life-changing, reaffirming, but then -

Remus opens his mouth and this is a kiss, not just mouth against mouth. He’s breathing Remus’s breath, warm against his mouth, and remembers carbon dioxide, respiration, and then he doesn’t care.

Remus’s mouth is hot, and he tastes of marking ink and coffee, of growing things and afternoon sunlight, color against Sirius’s face.

After awhile, Sirius has to pull away, dizzy on too little oxygen and too much of Remus’s mouth, and they look at each other for a long moment, back and forth, the tremulous electron of shared thought building between them, until neither of them can think of anything else at all.

“Maybe this, then,” Remus says, with a secretive smile that Sirius can suddenly decipher.

“Maybe this,” he agrees, and turns to pull up another weed with a smile of his own.

It’s surprising, Sirius thinks, how little things change between them. Every other friendship turned romance has been full of awkward pauses and uncertain boundaries, whether to tell your colleagues you’ve gotten together, whether to stay friends after, but this is easy. Hardly anything changes, even as he feels his world slowly beginning to slide into retrograde rotation.

There are half-exchanged glances over the dinner table, now, and perhaps Remus’s calf against his underneath. Sometimes they kiss, when they’re passing plates back and forth, and there are a few dizzying episodes on Sirius’s couch, kissing, with Remus pressed against him, warm hollows and hard planes, fitting just exactly right as they kiss, like teenagers, and for the first time since twenty, Sirius stops thinking of twenty-six as just-this-close-to-thirty.

There are four years he has no intention of slipping away, if they hold Remus’s hands against his stomach, rough-palmed and firm, and Remus’s mouth over his, with warm intensity and clear affection.

There is no question of how Remus feels about him; he wears his emotions in his eyes and on his hands, and slow gestures mean I care about you. Sirius can tell, like he’s never been able to tell with anyone, when he’s angry, when he’s tired - the tense line of his back that means he’s hurt or exhausted.

Being with Remus Lupin is easy, for three weeks and four days, and then Remus takes off his jumper, after their sixth official date, and undoes his cuffs, and murmurs, leaning half-in-half-out of Sirius’s doorway, “Have you done this before?”

“No,” Sirius says, then, “yes.”

He’s been with men before - a few times, in college, when he needed the bone-deep distraction of someone who wasn’t afraid to play rough, some post-game fucking around in the locker room, high on adrenaline and victory - but he doesn’t know how to articulate that this is different.

“I’ve been with men before,” Remus offers, with a slow, almost lazy smile, “but never with you.”

That, Sirius thinks, is exactly how he feels.

Then they’re kissing - hot, hard pressure, broad hands just under his shirt, and this, he thinks, whole body feeling like it’s at the bottom of a swimming pool, pressure and inescapable pull, is what he likes best about Remus: he’s not afraid to be hungry.

This close, and his whole body heats - he can feel himself getting hard against Remus’s stomach, pressing his hips forward as Remus laughs, so low he can feel it in every place they touch. He knows what it is to touch, to rub himself off against Remus’s warm thigh, the bright-eyed flush of orgasm across his face, and there have been a few slow blowjobs (the thought of a warm, wet mouth around his cock only makes him harder), but this is different - he can feel it in the tremble in his own hands, not nerves but excitement, and in the steady slam of Remus’s heartbeat against his chest, through two layers of clothing.

He can feel warm, demanding arousal pooling low in his stomach, knows the tightening of stomach muscles as he presses closer to be another symptom of this common infection of desire.

Remus makes a soft, rough noise in the back of his throat, pushes Sirius through two rooms and down, onto the bed.

Sirius thinks, maybe we should slow down, but he’s been too hungry for this for too long to stop the way Remus is kissing him, deep and hot and just a little bit dark, fingers spread across his ribs for balance. Sirius’s heart is doing triple time in his chest, and when Remus sprawls on top of him and pushes their hips together, he moans - shaky, shuddery, but loud, strange from the perpetually quiet one, in bed.

“Shh,” Remus says, laughing against the hollow of his throat, “you’ve got thin walls.”

He gets Sirius’s shirt off as Sirius unbuttons his, slides down to nuzzle against Sirius’s stomach, slow kisses between spread fingers, hot breath against already overheated skin. Sirius twists and laughs, trying to get away - less that it tickles than if Remus doesn’t stop, he’s going to come.

Remus pulls away, undoes his belt, and it takes both of them to get his trousers off, his boxers on the floor, but it’s worth it when Remus wraps a hand around him. He rubs his thumb just beneath the head of Sirius’s cock, and Sirius swallows, hard, breathing sliding into uneven. Remus isn’t slow, but he’s thorough - slow twist of his wrist on the upstroke, fingertips against the vein on the underside - and by the time he puts his mouth to Sirius’s erection, Sirius is so close he can feel his own heartbeat.

It doesn’t take much - two broad tongue-strokes across the head, slow, steady suction - before he comes, fingers tight in the sheets, back arching off the bed.

He rolls over, hands a little unsteady as he undoes the zip of Remus’s jeans, but the way Remus inhales when he slides a hand inside makes moving a little too quickly worth the trouble. It’s a little clumsy and inelegant, when they kiss, save for the low, hot noises Remus is making into Sirius’s mouth as he strokes, which go straight to his cock. There’s not enough room, not really, and he nearly gets his fingers caught in the zipper, but Remus is hot and hard in his hand, and he moans when Sirius’s fingers catch: oh fuck.

Remus makes him stop, though, long before he comes, pulling his jeans the rest of the way off. He settles down between Sirius’s thighs and they just kiss for awhile - as if just is an appropriate sort of adjective for this sort of kissing, all hot, breathless desire and tongues.

“Maybe we should’ve talked about this beforehand,” Remus murmurs, with a low laugh, when Sirius starts rubbing against him, hips pressed close, “because I don’t have - ”

And Sirius says, “Bedside table - ”

He’s absurdly grateful, for once, that he used to fuck women.

Remus grins above him, teeth white in the darkness, and fumbles a second light on, thrusting back down against Sirius as he reaches, and Sirius can’t think anymore.

“Do you want to - ” Remus begins.

“No, you,” Sirius answers, with a lazy smile, even though he hasn’t done this in years, and Remus laughs, as if he’s just as amused that they’re finishing each other’s sentences, this soon.

“Yeah,” he says, voice low, as Sirius stretches, arches, makes just enough room for Remus to roll over, between his thighs. He can’t see, quite - the angle’s all wrong - but he can hear Remus coat his fingers in lubricant, feel him slide one inside. This isn’t strange, not yet - he’s had girlfriends who have gone this far, before. Then two, and just enough pressure there to make his spine melt, then one more, and it’s not quite uncomfortable.

Then the pressure’s gone, and Sirius is panting, almost, with the need to do this, right now. He rolls over, hands-and-knees, and watches Remus open the condom - not with his teeth, as Sirius always does, even though he knows he shouldn’t - and put it on. His heart is somewhere back around his throat, and then there are steadying fingers down his spine that make him shudder, warm breath against his neck.

“Relax,” Remus whispers, and Sirius does, inexplicably, as Remus guides himself inside, hands steady on Sirius’s hips, pulling him back, just there.

He gives Sirius just enough time to adjust before he begins to thrust, hard enough that Sirius knows he’s going to feel it in the morning, but it’s good, all the same. Remus slides a hand around to curl around his erection, grip tight and fingers still slick, and it only takes a moment past that for Sirius to come, hard, as Remus leans in to close teeth against his shoulder, coming himself a moment later, breathing hard.

He pulls away and Sirius settles down onto the bed again, turning to meet his eyes. He’s smiling, and Sirius wonders, for a moment, how on earth they’ve gotten here. He finds he doesn’t particularly care.

“Shower?” Remus offers, and the last thing Sirius wants is to get up, but he knows he has to, or he’ll be exceptionally sorry come morning.

By the time they’re back in bed, warm and damp and curled around each other in ways that Sirius would stop to marvel at if he had the energy, he’s used to this already, perhaps a dangerous line of thinking.

“I was going to take your watch,” the voice comes, almost asleep, against his chest.

“What?” Sirius says, finally.

“The night we met,” Remus murmurs, “I was going to take your watch. They’d messed up my paycheck two months in a row, and I’d just come back from the worst Christmas of my life. My watch broke, and you can’t function as a teacher, without a watch, so I was going to take yours.”

“Why didn’t you?” Sirius says, soft in the darkness.

He can hear the laugh. “I liked you too much.”

“I think,” Sirius whispers, the first time he’s told anyone, “I was going insane, before you.”

“It’s all right now,” Remus replies, quietly, and rolls over to kiss him, slow and almost thoughtful, catching Sirius’s soft noise of agreement against his mouth.

And yes, Sirius thinks, the burning answer to the unanswered question - yes, Remus Lupin tastes of India.

Homg. I now do not know what to do with myself, my life has no meaning, blah blah blah. Anyway.

1. linnpuzzle and I teamed up.

2. There is this story. It is an AU fic in which Remus and Sirius are muggles and meet on a train and Remus is, in fact, a school teacher and Sirius is, like, an investment banker, and then, you know, it all goes downhill from there.

3. There are trains, Kipling, Wales, marking papers, and all sorts of other fascinating things.

4. THERE IS FANTASTIC, GENIUS, BEAUTIFUL ART from the hero of the world at large, Linn. Homg.

5. This fic was originally for sheafrotherdon's dissertation, but has not been posted anywhere other than her community, so it's like A BRAND NEW FIC. A long one, too.

6. Also, yes, the last pic may be colored. Linn's working on it. :X

Without further ado: Remus/Sirius, NC-17, AU, and, uh. Onward, soldiers.

Beware of not-incredibly-worksafe art, towards the end there. Like this is going to discourage anyone.

For girlsclub, with love, because you lot keep me going, especially yeats, imochan, and sheafrotherdon. (Also, hostile_21, but she's off in Tahoe, so to hell with her.)

The Moon's Significant Tremble

Sirius Black isn’t used to people sitting beside him on trains.

It’s four days past Christmas, edging into the desolate grey of the time just past the holidays when everything blends together into long nights and too much shovelling, and he’s coming back from Wales. Sirius has never been entirely sure what one does in Wales, but he goes twice a year, like clockwork, because it seems the sort of thing one ought to do, like sending Christmas cards and giving a few pounds to the heroin addict sleeping in the bus stop. It doesn’t matter that there’s nothing in Wales, just like it doesn’t matter that the Christmas cards will doubtlessly rest on the mantle for a few days before they’re thrown away, like no one bothers to care that the money will only go for more drugs, not a hot cup of coffee and a sandwich.

Sirius has a list of things he’d like to do, which always seem to fall into the no man’s land of his To Do List, lost in the perpetual haze of “when I get around to it.” They’re caught in the January of the bulletin board that hangs in his kitchen, with sprawled phone numbers. The scrap of paper that says Groceries! and the one that says Library books due - Thursday 3:00 PM are lucky, tangible like May, no easier to ignore than the first of the crocuses. They’re always taken care of, again and again, and sometimes Sirius thinks he ought to make a list and work his way down it. He’d like to live in an ideal world where the ultimate goal of visiting Nepal has equal weight in time to remembering to pick up his dry cleaning. He’d like the idea of not going to Wales to be as obtainable as buying laundry detergent, like to remember to carry a flask of coffee and sandwiches in the bottom of his briefcase, to give the man at the bus station something useful.

He’s twenty-six and floundering when he steps into the carriage, with thirty around the corner of the luggage rack and thirty-five in the chewing gum spots under the seats.

Then someone beside him asks to sit down.

He’s half here and half there, tugged two ways by the swish-swish-thunk lullaby of the train, unable to collect his thoughts. Brown eyes, he thinks, then, with the disconnection borne of sleeplessness and the sort of train that hugs the black curves of the hillsides - Kind.

“Sorry?” he says.

The man has a folded newspaper and glasses that slide down his nose. The elbows of his coat are patched, so threadbare that the coat itself seems to have gone beyond beloved into see-through, and he has the same quality - Sirius looks at him for a moment, feeling as if he’s looking through him instead of at him, even when he squints to focus.

“Do you mind if I sit here?” the man repeats, fingers tightening then releasing on the clasp of his bag.

The train is nearly empty, and Sirius wonders - he’s met a few too many of this type, in London. If he sleeps, he’ll wake up to find things missing. But the man’s shirt is clean and his trousers are pressed into starched perfection. There’s no wedding ring, but his watch is decent; too plain to be stolen, too expensive to signify desperation. It’s a few hours back to London, and Sirius doesn’t particularly want to spend those hours looking out the window into the inky blackness of England at night. His briefcase has a lock.

“Not at all,” he replies, finally, the right thing to do, and moves his bag.

The answering smile is almost enough to convince him. “Lupin,” the man says, extending a hand. “Pleasure.”

“Sirius Black,” he answers, and notes that the handshake is firm.

It’s surprisingly easy conversation, with the fluid quality that comes of talking to strangers. The holidays are a peace accord, an unsung grace - there is a slow, warm kinship between all of humanity, the dull roaring silence of the city at night, with the windows open. It’s being alone but unafraid, lying in the dark just before sleep comes, and knowing that beneath the dull hum of car tires through raindrops, there is the steady, even breathing of a thousand other people.

It’s impossible to be lonely in London, like being a single cell in a slowly waking organism, some rough beast slouching towards Bethlehem, but here, in the middle of nowhere on an almost-empty train, it’s expected, and therefore, a small point of wonder when his expectations fail.

Lupin talks with his hands - slow, expressive motions that captivate and hold tight. They’re strong, Sirius thinks, absently, as Lupin talks of India: a cupped gesture to indicate the Ganges, the indelicate curl of his fingers to show the slow slide of a mango down one’s throat. The hands of someone unafraid to work.

Sirius has always wanted hands like that. His own are pale, and the only calluses are those of pens, subtle nicks from thick paper, a broad scar across his palm; a cut from a kitchen knife as a boy, nearly through the tendon. He keeps them still and steady, balanced against the back of the seat in front of him, kept safely in his lap. Touch is an anchor, a lifeline. The man beside him trusts the tilting planet enough to let go; Sirius does not.

“With consideration to the constraints,” Lupin is saying, when Sirius surfaces from the warm lull of his voice, “I believe it’s possible.”

Venice, Sirius thinks, he’s talking of floodgates in Venice, but it only brings the knowledge of somewhere else Lupin’s hands have been. He wonders if his touch might be electric, enough to jolt him from here and the endless tedium of life, if their handshake has changed him on indiscernible levels.

He wonders if you can think that of someone you’ve met on a train, wonders, in the slow, dull heat of the carriage, pulled towards sleep by the reassuring sound of a deep voice, the half-sway of the train, if the broad, worn pads of Remus’s fingers feel warm, like he imagines the Venetian canals might.

“I wish,” he murmurs, too lost to follow the conversation, feeling the stray-electron hit of neurons firing, nothing to do with this, “I knew what India tasted like.”

There’s a long, startled half-blink from Lupin, as if Sirius has caught all of him off guard with the question, instead of just his mind and mouth.

“Like curry,” he says, finally, after a long pause, with a warm, quiet smile that Sirius feels complete the circuit. “Like curry, and like rain.”

He failed chemistry, can’t remember the laws of biology, but this, he thinks, this, he knows, is what they meant, all along -

He needs to know this man.

When he falls asleep around midnight, Lupin is still talking, voice low and lilting. The dull hiss of air through compartment doors and the slow footsteps of the conductor are all the lullaby he needs; he wakes to the gentle press of fingers against his shoulder.

“Nearly there,” Lupin murmurs, with a smile that makes his stomach flip over, like the prospect of sex or unsettling news, the dull-steady tempo between action and reaction, tension and release.

“Sorry,” he mumbles, still tired, disoriented, the lights of London flashing by in the darkness, pinpricks of white amidst the January black. “I must have been more tired than I thought.”

“Not a problem,” Lupin replies, then gestures to the book at Sirius’s feet, the one he’s forgotten he had - “Kipling. No one much reads Kipling anymore.”

Sirius somehow doesn’t want to admit that he doesn’t particularly like it - too dark in the heart of things, too tense, as if the pages are too thin for all they hold. “I’ve only started,” he says, instead - not a lie, if three-quarters through is beginning.

“Beautiful prose,” Lupin murmurs. “May I?”

Sirius passes over the book, and Lupin pulls a pen from his jacket pocket, tarnished but delicate, probably an heirloom. “Do you mind?” he says, and Sirius shakes his head.

He writes his name on the inside cover, just behind the dust jacket, against the edge, Remus Lupin, and Sirius thinks it’s an oddly fitting first name, longs to see how it tastes, but can’t quite bring himself to - and then, his number underneath, small and perfect, in the penmanship of someone who has never forgotten grade school lessons.

“I rather enjoyed the discussion,” he says, finally, with another stomach-twisting smile. “If you wanted to ring, sometime - ”

“I’d like that,” Sirius replies, and wonders if this is what friendship is like when you care about what the other person thinks, this half-caught flutter in your chest, the imperceptible tightening of stomach muscles, like asking someone to dinner or speaking to an author at a book signing.

Remus stands, collecting his sole, lonely piece of luggage as the train slides to a stop, and Sirius loses sight of him in the dim, two-am-shadows of the train station, all florescent lights and washed-out faces, people whose only desire is to be somewhere, not caught in the limbo of faded travelers and the dull buzz of lights, with the puddle of water just inside the doors, the dull roar of taxis outside on the street.

It’s only when he gets home, into the open arms of a dark, empty flat, with the mail piled inside the door and no milk in the fridge, that he realizes he’s left his book on the train, in Remus Lupin’s seat, and try as he might, he can’t recall the crisp, sharp numbers left on it.

He falls into his own bed, made deeply unfamiliar by just a few days away, and thinks that he’ll call in the morning, too tired to consign Remus Lupin to temporary life as a note on his bulletin board.

He remembers, somehow, when he wakes, and in the woolen-dark of another January morning, he calls the train station, which says they’ll watch for his book but fail to take his number. He tries directory assistance, but the number is unlisted, and he tries to tell himself the low pang in his chest is absurd, that the loss of a stranger on a train is hardly worth thinking twice over.

He didn’t like the book anyway.

He forgets.

It’s almost a month later the next time he’s on a train, Valentine’s Day, with low, bitter edges and quiet regret. He’s coming back from visiting his mother - the institution in the countryside, so tragic for a mind to go at such a young age - and the creeping edges of loneliness are like the frost that builds against the windowpane; all right if avoided, too hard-broken cold to touch.

He stares out the window into the dark until the attendant comes by with the cart, and they’re almost the only people on the train. He turns to look at her for a long moment and the slow reflection of this is there; she’s working too late on a holiday to be anything but alone, he’s on a midnight train from nowhere.

“Going home to someone?” she says, with false brightness, shadows underneath like edges of layered paper, over and over again, and her eyes are too old for the youth of her face.

“Unfortunately not,” he murmurs, with a tight, quiet smile, and here, he knows, it is again, the slow, familiar stomach flip at her half smile of sympathy, of kinship.

He could have someone warm in his bed tonight, and she’s pretty, with dark eyes and small breasts that he can catch the edges of through her uniform, too cold in here for the short sleeves she wears. Let me give you my coat, he could say, you look cold, and then she might sit beside him, later, and in the slow, smudged blinks between now and four in the morning he might not be so alone. He can imagine, in half a second, what her breasts could feel like cupped in his hands, how her pulse might beat beneath his mouth, sweet and rapid in the hollow of her throat, how she might feel around him, warm and slow and oh god there.

He doesn’t want it.

“Coffee, please,” he says, quietly, and doesn’t let his fingers touch hers as he hands over the money.

It isn’t until he’s halfway home on the underground that he realizes he’s left his keys on the train, but London’s the last stop of the night, and he thinks that perhaps he can catch the cleaners before a locksmith becomes necessary.

They direct him to a room of lost and found items, and he finds his keys on a low shelf, lost amongst the mittens and gloves of a never-ending season. When he stands, he catches sight of a familiar dust jacket peeking out from a faded purple jumper, and slow, unsteady hands pull it out again, memory too tangible to have really been erased.

Understanding, he thinks, and as he unfolds the cover, there it is - ink unfaded, letters as crisp as the day they were written.

Remus Lupin, and a slow, clear column of numbers.

He tucks the book inside his jacket, close to his heart, and goes home.

He rings the next morning - too early, with the sun just coming in over the snow that covers the windowsill, dyeing it orange, and listens to the slow click of the connections, the dull, tin-coated ring. Someone picks up, and he can hear sleepy breathing, distorted by the bad connection that comes from calling the wrong part of town, where no one much gives a damn about phone connections.

“Hello?” the voice comes through, recognizable even through static, and Sirius thinks, for a moment, that he ought to have planned out what to say, because he’s close to saying everything he’s ever needed to say to a stranger he’s met once, on a train, in the middle of the night. I’m lonely, he nearly says. I’m afraid of staying like this for the rest of my life. He wonders if he’s turning into his mother, hearing voices in his head.

“It’s Sirius,” he says, finally. “Sirius Black, from the train.”

There’s a dull hum of recognition, but the voice on the other line doesn’t say all the things Sirius expects it to, such as why are you calling at half six or I’m afraid I don’t remember. Instead, it surprises him. “What are you doing this afternoon?”

Remus is taking a group of his students - somehow, the fact that he’s a professor feels right to Sirius; teach me, he wants to tell him - to the Natural History Museum, and he wonders if they might meet after. Admission is free, it’s warmer than the street (said ruefully, as if there’s first-hand knowledge to back it), and perhaps they might have something to eat, after.

“Yes,” Sirius says, instantly, firmly, and looks forward to getting off work for the first time in longer than he can remember.

The next time he sees him, it’s half four, and he’s standing in the Central Hall beneath the skeleton of something large and imposing, all arches and angles, the late-afternoon sunlight spilling in from cathedral windows onto him, lighting him gold.

Sirius waits a moment, just watching, as the crowds spill around him, schoolchildren with bags from the gift shop, women in knee-length woolen coats, a man pacing back and forth, back and forth, across the length of the thing.

Lupin stands still, eyes half-closed, gilded in light and the dust moats of a thousand footsteps, steady with obvious reverence for this something. Sirius has always simply walked by, hardly even noticing the hulking statue, in a hurry to get to things more glamorous; the gallery of jewels, the human remains. Here, though, he can see the slow curve of age set in stone, the butterfly-wing fragility of this. He understands, for half a moment, what it is to be here, in this moment, and he finds it strange that he feels alive for the first time in months standing in the hall of a museum he’s never really enjoyed, watching a stranger enjoy a skeleton.

“Lupin,” he says, finally, stepping across the stone to stand in the sun behind him.

“Beautiful, isn’t it,” he replies, not looking away from the dinosaur.

“No,” Sirius murmurs, honestly. “But it’s worth looking at.”

Lupin smiles. “It is indeed. My students rush by, but I believe it’s my favorite part of the museum.”

“Mine too,” Sirius says, and is almost surprised to find he isn’t lying.

Dinner is a small, nearly empty Indian restaurant a few blocks down. It’s not luxurious, but it’s warm, and the food is cooked as they wait. “I’m sure you’re used to better,” Lupin says, in the tone of someone too familiar with poverty to be ashamed, anymore, “but teaching isn’t exactly a high-end profession.”

“Don’t be daft,” Sirius says, finally, even if he is. The flicker of a dim light across Remus’s face is enough to make up for the plastic serving ware, and to his surprise, the food is better than most restaurants he’s been to.

He’s not sure where the evening goes, but the next time he looks at his watch, it’s nearly eight and he’s on his fourth cup of coffee. “I don’t live far from here,” Lupin says.

“I’ll walk you home,” Sirius replies.

The cold is biting, even in the city, but the company is enough to keep him warm - easy banter back and forth about the book Sirius read a week ago, the most recent political scandal. Lupin climbs the stairs to a door, turns three different keys in three different locks. “Too cold for trouble,” he says, with a smile. “But I’d take a cab home.”

“Goodnight, Lupin,” he replies, gloved hands stuffed in his pockets against the cold.

Lupin half-turns, door already open. “Remus,” he says, finally. “It’s Remus.”

“Remus,” Sirius whispers, as he closes the door behind him, and it feels exactly like he imagined it would, in his mouth.

The next month slides by in the slow inevitability of phone calls - some in the middle of the night - and movies - foreign and drama; they can’t agree on anything else. Sirius thinks, both, that he has never known someone so well and that he has never known someone so little.

This is someone who he can call at half four in the morning when he can’t sleep, and, worse still, can’t get the last block of the crossword. Remus, he discovers, makes better coffee than anyone else in England, and sometimes, in an act that Sirius doesn’t understand, he comes to mark papers at Sirius’s kitchen table while Sirius watches BBC or tries to read.

He only goes to Remus’s flat twice. The first time, he merely steps in while waiting for him to get his coat, wary of tracking London snow on the entryway carpet. The walls are the white that signifies ownership by someone who can’t afford not to get his security deposit back, and trains rattle by at all hours of the night, so Remus can’t hang things on walls. There’s not enough hot water, Remus says, and the pipes tend to freeze in winter - the second time Sirius is there, he’s helping to fix one - but it’s close enough to the school that he can walk, even in winter, and the rent’s low enough that he can put a little away.

It’s the proximity to school, though, Sirius knows, that makes Remus tolerate the faulty wiring and leaky windows. He sees him teach only once, but there’s enough passion in Lupin’s voice to make Sirius wish that he’d had a teacher such as Remus Lupin. If he had, he thinks, he wouldn’t be where he is today. For the first time in years, however, he entertains the possibility that where he is could be something close to all right.

He isn’t sure what he’s doing - isn’t sure if this is how things are supposed to be or if this is strange, if everything before this has been right and this is wrong, or if it’s the other way around. He knows that he doesn’t lose much sleep at night, anymore, and that being alone doesn’t hold quite so much agony, but he worries, sometimes, that it’s dangerous, to place all one’s faith in one person, if it’s acceptable for a man to love another man as he loves Remus.

It’s like falling, slow and unsteady, with water and out held hands to break your fall. Doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt when you hit, he thinks, the only time the analogy occurs to him, but wariness is not enough to prevent trust.

He only sleeps with one woman in the first two months he knows Remus. She’s tall and just the right shade of off-color brunette, quiet and well-spoken. She talks with her hands.

It’s not bad - Sirius doesn’t think he’s so far gone that sex could be bad, not like this - but when she rolls out of bed in the morning and takes one of his shirts with her, he doesn’t bother to call again. A bed that felt of another person used to be a comfort, but he washes the sheets twice and gives away the jumper she leaves on his sofa.

Things are comfortable again, after that - nothing just under his skin, taut and irritating - and then, just as quickly, they’re strange once more.

He’s helping Remus pull weeds around the crocuses in his small scrap of flowerbed, dirt under his nails, cheeks flushed from the cold spring wind.

“What are we doing?” Remus murmurs, finally, looking at Sirius’s hands, then his own, then the purple and yellow flowers between them.

“Pulling up weeds,” Sirius answers, without really thinking about it, and then he’s acutely aware that Remus is watching him, with the same scrutiny he applies to things he thinks are beautiful - dinosaur skeletons and small flowers and an exceptionally well-written paper.

“Not that,” Remus says, softly, and leans back on his heels.

Sirius puts his trowel down slowly, heart in his throat, where he can feel it - thud thud thud. “I don’t know,” he says, watching the slow, thoughtful curl of Remus’s fingers in his lap, against faded blue jeans and the hem of an old cotton jumper.

Red is a bad color on him, Sirius thinks, absently, and he thinks perhaps this isn’t the sort of thing you ought to be thinking of, when you’re leaning in, like this. He thinks this might be another science lesson - gravity, this time around, elemental forces, but then the thud of his own blood in his head drowns out everything, and he doesn’t think at all.

It might be nothing, this pull, might be the attraction of a lost eyelash on his cheekbone, to be brushed away with a thumb, might be the magnetic pull of the sun in Remus’s eyes or the tidal tug of a smudge of dirt on his nose.

But Remus lifts a hand, there, to curl against his jaw, thumb just brushing against the corner of his mouth, eyes shuttered and unreadable, and this, Sirius knows, is the very definition of in too deep, because you can’t step back from the look in his eyes.

Maybe, he thinks, this isn’t what I think -

Then Remus leans in and kisses him, in full view of all of London, and all Sirius can see is his face and the electric blue spring sky behind. It’s just the press of mouth to mouth, nothing that ought to be amazing, and he’s done it four thousand times before. It’s not amazing, he thinks, almost disappointed in something that he thinks ought to be life-changing, reaffirming, but then -

Remus opens his mouth and this is a kiss, not just mouth against mouth. He’s breathing Remus’s breath, warm against his mouth, and remembers carbon dioxide, respiration, and then he doesn’t care.

Remus’s mouth is hot, and he tastes of marking ink and coffee, of growing things and afternoon sunlight, color against Sirius’s face.

After awhile, Sirius has to pull away, dizzy on too little oxygen and too much of Remus’s mouth, and they look at each other for a long moment, back and forth, the tremulous electron of shared thought building between them, until neither of them can think of anything else at all.

“Maybe this, then,” Remus says, with a secretive smile that Sirius can suddenly decipher.

“Maybe this,” he agrees, and turns to pull up another weed with a smile of his own.

It’s surprising, Sirius thinks, how little things change between them. Every other friendship turned romance has been full of awkward pauses and uncertain boundaries, whether to tell your colleagues you’ve gotten together, whether to stay friends after, but this is easy. Hardly anything changes, even as he feels his world slowly beginning to slide into retrograde rotation.

There are half-exchanged glances over the dinner table, now, and perhaps Remus’s calf against his underneath. Sometimes they kiss, when they’re passing plates back and forth, and there are a few dizzying episodes on Sirius’s couch, kissing, with Remus pressed against him, warm hollows and hard planes, fitting just exactly right as they kiss, like teenagers, and for the first time since twenty, Sirius stops thinking of twenty-six as just-this-close-to-thirty.

There are four years he has no intention of slipping away, if they hold Remus’s hands against his stomach, rough-palmed and firm, and Remus’s mouth over his, with warm intensity and clear affection.

There is no question of how Remus feels about him; he wears his emotions in his eyes and on his hands, and slow gestures mean I care about you. Sirius can tell, like he’s never been able to tell with anyone, when he’s angry, when he’s tired - the tense line of his back that means he’s hurt or exhausted.

Being with Remus Lupin is easy, for three weeks and four days, and then Remus takes off his jumper, after their sixth official date, and undoes his cuffs, and murmurs, leaning half-in-half-out of Sirius’s doorway, “Have you done this before?”

“No,” Sirius says, then, “yes.”

He’s been with men before - a few times, in college, when he needed the bone-deep distraction of someone who wasn’t afraid to play rough, some post-game fucking around in the locker room, high on adrenaline and victory - but he doesn’t know how to articulate that this is different.

“I’ve been with men before,” Remus offers, with a slow, almost lazy smile, “but never with you.”

That, Sirius thinks, is exactly how he feels.

Then they’re kissing - hot, hard pressure, broad hands just under his shirt, and this, he thinks, whole body feeling like it’s at the bottom of a swimming pool, pressure and inescapable pull, is what he likes best about Remus: he’s not afraid to be hungry.

This close, and his whole body heats - he can feel himself getting hard against Remus’s stomach, pressing his hips forward as Remus laughs, so low he can feel it in every place they touch. He knows what it is to touch, to rub himself off against Remus’s warm thigh, the bright-eyed flush of orgasm across his face, and there have been a few slow blowjobs (the thought of a warm, wet mouth around his cock only makes him harder), but this is different - he can feel it in the tremble in his own hands, not nerves but excitement, and in the steady slam of Remus’s heartbeat against his chest, through two layers of clothing.

He can feel warm, demanding arousal pooling low in his stomach, knows the tightening of stomach muscles as he presses closer to be another symptom of this common infection of desire.

Remus makes a soft, rough noise in the back of his throat, pushes Sirius through two rooms and down, onto the bed.

Sirius thinks, maybe we should slow down, but he’s been too hungry for this for too long to stop the way Remus is kissing him, deep and hot and just a little bit dark, fingers spread across his ribs for balance. Sirius’s heart is doing triple time in his chest, and when Remus sprawls on top of him and pushes their hips together, he moans - shaky, shuddery, but loud, strange from the perpetually quiet one, in bed.

“Shh,” Remus says, laughing against the hollow of his throat, “you’ve got thin walls.”

He gets Sirius’s shirt off as Sirius unbuttons his, slides down to nuzzle against Sirius’s stomach, slow kisses between spread fingers, hot breath against already overheated skin. Sirius twists and laughs, trying to get away - less that it tickles than if Remus doesn’t stop, he’s going to come.

Remus pulls away, undoes his belt, and it takes both of them to get his trousers off, his boxers on the floor, but it’s worth it when Remus wraps a hand around him. He rubs his thumb just beneath the head of Sirius’s cock, and Sirius swallows, hard, breathing sliding into uneven. Remus isn’t slow, but he’s thorough - slow twist of his wrist on the upstroke, fingertips against the vein on the underside - and by the time he puts his mouth to Sirius’s erection, Sirius is so close he can feel his own heartbeat.

It doesn’t take much - two broad tongue-strokes across the head, slow, steady suction - before he comes, fingers tight in the sheets, back arching off the bed.

He rolls over, hands a little unsteady as he undoes the zip of Remus’s jeans, but the way Remus inhales when he slides a hand inside makes moving a little too quickly worth the trouble. It’s a little clumsy and inelegant, when they kiss, save for the low, hot noises Remus is making into Sirius’s mouth as he strokes, which go straight to his cock. There’s not enough room, not really, and he nearly gets his fingers caught in the zipper, but Remus is hot and hard in his hand, and he moans when Sirius’s fingers catch: oh fuck.

Remus makes him stop, though, long before he comes, pulling his jeans the rest of the way off. He settles down between Sirius’s thighs and they just kiss for awhile - as if just is an appropriate sort of adjective for this sort of kissing, all hot, breathless desire and tongues.

“Maybe we should’ve talked about this beforehand,” Remus murmurs, with a low laugh, when Sirius starts rubbing against him, hips pressed close, “because I don’t have - ”

And Sirius says, “Bedside table - ”

He’s absurdly grateful, for once, that he used to fuck women.

Remus grins above him, teeth white in the darkness, and fumbles a second light on, thrusting back down against Sirius as he reaches, and Sirius can’t think anymore.

“Do you want to - ” Remus begins.

“No, you,” Sirius answers, with a lazy smile, even though he hasn’t done this in years, and Remus laughs, as if he’s just as amused that they’re finishing each other’s sentences, this soon.

“Yeah,” he says, voice low, as Sirius stretches, arches, makes just enough room for Remus to roll over, between his thighs. He can’t see, quite - the angle’s all wrong - but he can hear Remus coat his fingers in lubricant, feel him slide one inside. This isn’t strange, not yet - he’s had girlfriends who have gone this far, before. Then two, and just enough pressure there to make his spine melt, then one more, and it’s not quite uncomfortable.

Then the pressure’s gone, and Sirius is panting, almost, with the need to do this, right now. He rolls over, hands-and-knees, and watches Remus open the condom - not with his teeth, as Sirius always does, even though he knows he shouldn’t - and put it on. His heart is somewhere back around his throat, and then there are steadying fingers down his spine that make him shudder, warm breath against his neck.

“Relax,” Remus whispers, and Sirius does, inexplicably, as Remus guides himself inside, hands steady on Sirius’s hips, pulling him back, just there.

He gives Sirius just enough time to adjust before he begins to thrust, hard enough that Sirius knows he’s going to feel it in the morning, but it’s good, all the same. Remus slides a hand around to curl around his erection, grip tight and fingers still slick, and it only takes a moment past that for Sirius to come, hard, as Remus leans in to close teeth against his shoulder, coming himself a moment later, breathing hard.

He pulls away and Sirius settles down onto the bed again, turning to meet his eyes. He’s smiling, and Sirius wonders, for a moment, how on earth they’ve gotten here. He finds he doesn’t particularly care.

“Shower?” Remus offers, and the last thing Sirius wants is to get up, but he knows he has to, or he’ll be exceptionally sorry come morning.

By the time they’re back in bed, warm and damp and curled around each other in ways that Sirius would stop to marvel at if he had the energy, he’s used to this already, perhaps a dangerous line of thinking.

“I was going to take your watch,” the voice comes, almost asleep, against his chest.

“What?” Sirius says, finally.

“The night we met,” Remus murmurs, “I was going to take your watch. They’d messed up my paycheck two months in a row, and I’d just come back from the worst Christmas of my life. My watch broke, and you can’t function as a teacher, without a watch, so I was going to take yours.”

“Why didn’t you?” Sirius says, soft in the darkness.

He can hear the laugh. “I liked you too much.”

“I think,” Sirius whispers, the first time he’s told anyone, “I was going insane, before you.”

“It’s all right now,” Remus replies, quietly, and rolls over to kiss him, slow and almost thoughtful, catching Sirius’s soft noise of agreement against his mouth.

And yes, Sirius thinks, the burning answer to the unanswered question - yes, Remus Lupin tastes of India.