Thoughts on Dancing on the Edge...

Don’t ask me how, but I’ve managed to get my hands on the first three episodes of Stephen Poliakoff’s Dancing on the Edge, and as you might have expected - I have thoughts. Plenty of ‘em. Hopefully the final two episodes will be in my grasp soon; when that happens I’ll put together a follow-up post.

Here There Be Spoilers

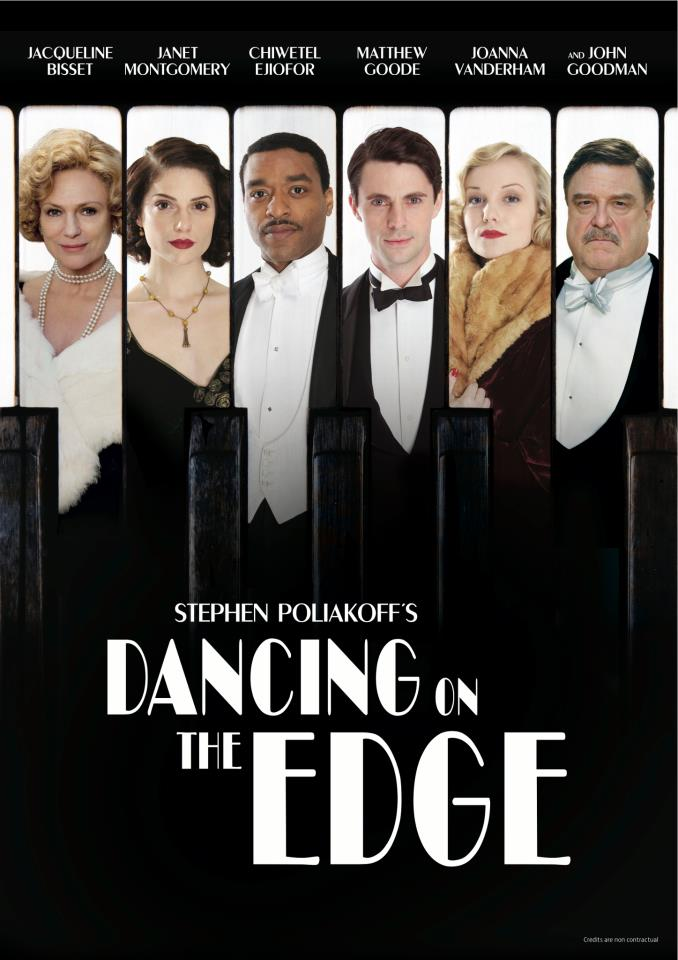

So, my first observation was one that I suspected I’d have ever since seeing the show’s poster/DVD cover. On being asked what Dancing on the Edge was about, I would imagine most people would say: “a black jazz band in the 1930s”. Now take a look at the promotional poster:

Yeah. See a discrepancy anywhere? Fact is, Dancing on the Edge is less about the trials and tribulations of a black jazz band as it is about white people reacting to the presence of a black jazz band in their midst (as well as getting up to a bunch of other stuff that has nothing to do with them at all). Ironically, it was overwhelmingly images of Angel Coulby that made up the bulk of the show’s publicity - particularly that picture of her in the silver dress standing at the microphone - and yet Jessie Taylor isn’t a hugely prominent character in the series, even taking into account her role as a murder victim.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I’ll backtrack.

It’s 1933 in London, and after a brief prologue in which we see Louie Lester (Chiwetel Ejiofor) and Stanley Mitchell (Matthew Goode) discuss their former’s desperate need to leave the country, we flash back eighteen months to see the events that led to the downfall of the Louie Lester band.

Louie is established as a piano player desperately trying to keep his American jazz band from getting deported back to the States by lining up a number of short-term gigs in basement clubs. Stanley in the meanwhile is an ambitious young writer at the Music Express, always on the lookout for the next big thing. He manages to secure a residency for the band at the Imperial Hotel, where guests and management alike run the gamut from astonished to disgusted at their presence. However, after adding a couple of singers (Wunmi Mosaku and Angel Coulby) to the line-up, things begin to improve for the band - particularly when the Prince of Wales signals his approval. There’s a great moment when the band play their first number to the royals, silence falls for just a moment over the crowd, the prince begins to clap, and immediately everyone else follows suit.

From this point, we’re left with a massive cast of characters to contend with, all of whom seemingly have something to hide. The band picks up some groupies in the form of aristocratic siblings Julian and Pamela (Tom Hughes and Joanna Vanderham). Man of leisure Donaldson (Anthony Head) takes an interest and offers his advice. US millionaire Masterson (John Goodman) decides to treat them as his new favourite toy. Eventually Stanley ropes in the patronage of Lady Lavinia Cremone (Jacqueline Basset), a reclusive widow who takes a shine to their young singer. Then there’s Sarah (Janet Montgomery), a photographer and friend of Pamela, Rosie (Jenna Louise Coleman), Stanley’s secretary, and Wesley (Ariyon Bakare) the band manager. It’s an eclectic group of people who have virtually nothing in common besides an appreciation for jazz music and an acknowledgement that the Louie Lester band might turn out to be a valuable commodity.

The series revolves around the interactions of this extensive cast, particularly Louie/Stanley, Stanley/Pamela and Louie/Sarah, and though there’s an undercurrent of sinister goings-on and constant reminders of the band’s precarious situation, it’s also a meandering journey that has no real urgency and keeps the characters at arm’s length throughout its duration. Try as I might, I couldn’t really connect with any of them, and though there are some standout performances, we never really get invested in any of their stories. It’s always impossible to pinpoint why and how some characters can suck you in whilst others can leave you apathetic, and though it differs from viewer to view, I definitely had the latter reaction in regards to Dancing on the Edge.

The pacing is extremely slow; one might even say sluggish. Agonizing even. Poliakoff likes to take his time, this I know, but here it gets a little absurd by just how achingly slow it all is. More than that, it often suffered from what I call the “so what?” syndrome. This is a phenomenon that occurs when you’re reading/watching a story unfold and frequently find yourself thinking: “so what?” Stanley is sleeping with this secretary. So what? Masterson takes the band and some guests on a mystery train trip. So what? Stanley has sex with Pamela on said train trip. So what? Julian decides to sell English cheese to the French. So what? A waiter mentions to Louie that his music is helping the future king with his sexual conquests. So what? Stanley and Louie play a prank on the Germans in their own embassy. Yes, but SO WHAT??

Granted, I should reserve judgment on some of these plot developments as there are still two more episodes to go, but at this point it’s difficult to see the point of such scenes. This might be a side effect of the lack of momentum in the plot, but also in the lack of clarity in what this show is fundamentally about. If it stuck with the rise and fall of the band, perhaps with a few subplots here and there, that would be one thing, but instead it plays out like a series of vignettes concerning a range of subjects that are tenuously linked at best.

Basically, everything is touched on, nothing is explored. Here is some institutionalized racism in the form of the band’s constant need to check in at the Alien Registration Office. There is some class tension in showing the band witnessing hotel staff throwing out piles of delicious food before being served cold soup and bread. Here’s a reminder of the changing technology of the 1930s when Stanley is saddled with a co-writer who wants to fill the magazine’s pages with news of inventions and gadgetry. Throw in some freemasons in the basement, some enigmatic behaviour from the wealthy, the mysterious stabbing at the end of episode two (which is handled with incredible calm by the rest of the cast), and you end up with a show that meanders.

There are four characters that stuck out, though admittedly I was heavily biased toward at least one of them. Though Stanley and Louie are strong leads, it’s the siblings Julian and Pamela and singers Carla and Jessie that I was most interested in.

Obviously, Angel Coulby was what brought me to the show, and the opportunity to see her sing and perform was totally worth it. She’s brilliant, somehow managing to pull off charisma as well as shyness, and also a little brattiness as well. Which is all down to her acting, as once again, the script gives her little to work with. We learn absolutely nothing about her character’s background or friendship with Carla, and it’s down to the actresses to give the characters the nuances they need. Solely by their interactions we can tell that Jessie is the dominant one in the relationship, and it’s quite a lovely juxtaposition to have the tiny petite Jessie in that role, whilst the taller, larger Carla follows her lead.

And yet despite her beautiful voice, Angel doesn’t get a lot to do. There’s only one scene in which we get a real glimpse into her character, and that’s when she gets on her knees and prays before her first performance. Carla gets a bit more depth despite being more introverted than Jessie, characterized as something of a worrywart who can’t quite believe all her good fortune and so just trying to enjoy it while it lasts.

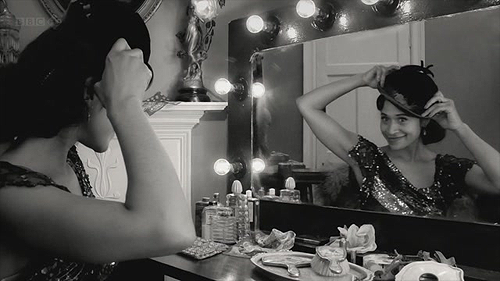

But they do have one of the show’s best scenes. Having decided to look fabulous on the night they’re scheduled to perform at the Imperial, they deck themselves in a velvet/sequined evening dress and swagger through the hotel foyer as though they own the place. Jessie knows full-well that she looks fantastic and takes it in her stride, but it’s adorable the way Carla keeps glancing over at her with a tiny smile on her face, as though not quite sure whether they’re going to get away with this.

There’s also Julian and Pamela, the aristocratic brother and sister. Not only do the actors easily pass as siblings (there’s something similar about the eyes) but each one is intriguing in their own way. Both are cold and a bit detached, yet earnest and eager to please. Their dull eyes bring to mind a perpetual drug stupor and Pamela in particular often sounds like she’s reciting dialogue rather than speaking naturally (I think this was a conscious choice from the actress). They both speak in low, measured voices, and yet there’s a subtle sense of desperation about them - yet desperation for what, exactly? There is an aura of fragility to them that contrasts nicely with the precarious position of the jazz band; you get the sense that they’re both teetering on the edge of a complete mental breakdown - but why is as yet unknown. It’s impossible to guess what either of them might be thinking at any given moment, so you’re left constantly trying to figure them out.

And yet despite their obvious vulnerability, they pose a very real threat. There is one particularly suspenseful scene in which Julian requests Louie’s help (only Louie’s help) and leads him up to Masterson’s hotel suite. Immediately you’re suspicious, a feeling that intensifies when it’s revealed that the suite has been trashed and there’s a bruised, drunk girl lying semi-unconscious on the bed. At this point you’re mentally urging Louie to get out of there before he is inevitably blamed for something he didn’t do, but Julian’s insistence that “you can leave if you feel uncomfortable/I won’t force you to stay if you don’t want to” compels Louie to stay.

When Julian asks him to help him clean up the mess and take the girl out to a waiting car (as per Masterson’s orders) you’re practically screaming at him to flee, and your heart is in your throat as he walks down the shadowy corridors with her in his arms, having a near-miss with one of the hotel staff, knowing full well what would happen if he’s caught with an inebriated white woman in his arms. Heck, Louie almost looks as surprised as I was when the whole thing goes off smoothly.

But these moments of suspense and subtlety are few and far between, simply because Poliakoff isn’t very good with the “show, don’t tell” rule. Information about the characters is invariably demonstrated by them sharing anecdotes about their lives, even when the recipient of their info-dumps would surely already know their backgrounds. This is especially apparent when Wesley is waiting at the registration office and decides to tell Louie why he’s so terrified at the prospect of returning to America: because he slept with a white woman and was accused of rape by her husband, which would result in execution if he was ever put on trial.

Yet it’s staged so oddly, with Wesley seemingly trying to goad the secretary into listening to his story while Louie tries to hush him.

Later, Lady Cremone confides to Stanley that she likes to seek out new things because it makes her feel closer to her sons that died in the war. Surely there was a way to SHOW this sentiment to us rather than just having her state it, especially since she had already been characterized as an immensely private person who doesn’t trust journalists. Yet now she’s entrusting that incredibly personal bit of information about herself to a journalist that put her picture on the front of his magazine without her permission? Really?

These are but two of the ways in which Poliakoff’s dialogue comes across as gratingly obvious. And though it may seem like nit-picking just two pull out two examples, the fact is that it happens all the time. People wax lyrically about themselves and their situations in lengthy monologues that sound incredibly unnatural and so end up feeling like a lazy way of getting across characterization.

Likewise, sometimes the foreshadowing is blatantly obvious. The number of times Wesley mentions his lost birth certificate is painful, as is a scene in which Julian throws a dagger-like implement on Stanley’s desk and explains where it’s from and what it’s for. Masterson is caught by two different people with a vast collection of gold, and feels the need to discuss its purpose to them in speeches that could have been condensed into: “This is a clue. Pay attention to it, as it will be important later.”

Other bits just sound like - well, something a scriptwriter would write because he thinks it sounds good, even though it doesn’t translate at all to the screen. Take this dialogue between Sarah and Louie after they’ve snuck away to Stanley’s office that is covered in photographs Sarah took earlier in the week.

Louie: What’s the matter?

Sarah: It’s just a little strange. Being watched by all of them.

Louie: Well I could take them all down.

Sarah: No you don’t, it’s my photographs, remember? On second thoughts, I can easily cope with them.

The real clincher? They’re making love at the time. Seriously, they’re completely naked, wrapped around each other and rolling about in bed when Sarah comes out with this little observation. It just doesn’t work. At all.

But that’s not to say that there isn’t some good stuff in here. Poliakoff initially builds up a pretty good contrast between Louie and the band manager Wesley, one that is exemplified when Wesley starts overstepping his boundaries. They initially act as foils to one another, with Louie established as calm, responsible and soft-spoken, a man who maintains a very careful façade of manners and graciousness in order to soothe the white people around him, knowing full well the precariousness of the position he’s in. He knows that if he’s to get anywhere in the upper class white world, it has to be on THEIR terms, and so is forever trying to negotiate his own integrity with a refusal to react in any overtly negative way to the racism that surrounds him. This is actually pointed out by Stanley on a couple of occasions, who is astonished by his infinite patience.

Wesley on the other hand, has no patience whatsoever. When he sees injustice, he reacts with anger and resentment, and once the band achieves a measure of success, he starts breaking the rules: stealing food, inviting women up to his room and so on. Naturally (as he points out) this isn’t anything that white guests don’t do on a regular basis, but it’s obvious to Louie that the consequences for such transgressions will be quite different. Yet he’s not an ineffective manager. He manages to negotiate a deal with the hotel manager Schlesinger that will see the band booked for a four month period (he aims for six, Schlesinger demands two, and Louie rounds it up to four) which was virtually unheard of at the time.

Yet his contentious attitude damns him. He’s not prepared to “play the game” like Louie is. Louie survives because he stifles anything that could make white people uncomfortable (even when Sarah and Donaldson urge him to tell a story about his personal experiences with prejudice, there’s still a slight note of apology in his voice), whilst Wesley wants to be treated as an equal, even though his demeanour makes Sarah and other white guests visibly uneasy. It’s impossible to say which man is “right” in their choice of behaviour, but naturally Schlesinger seizes the first opportunity he can get to get rid of Wesley by capitalizing on his lost birth certificate. When Wesley realizes that he’s being deported because he doesn’t have the right documents, he goes on a rampage around the hotel, smashing vases and overturning tables whilst Stanley and Louie try to calm him down.

Naturally he doesn’t, considering this is a matter of life and death for him, and he points out to Louie (who does everything in his power to save Wesley even though he knows on some level that he’s a liability) that the likes of Stanley won’t be around to save him if times get tough - a sentiment that has yet to be put to the test. It’s a gripping scene, one of the show’s best, in which you’re torn between thinking that Wesley is righteously furious about the corner he’s been shoved into, and unutterably stupid for the scene he’s creating.

The episode ends with a wonderful montage of scenes that flit between the band preparing for the performance for the Prince of Wales and Wesley waiting anxiously in the deportment office, waiting for the phone call that will save him. It never comes, and as Wesley is shuffled into a waiting bus, the band enjoys rousing applause at the Imperial. As it was Donaldson who was meant to make the all-important phone call, one can’t help but think that it was all a conspiracy to get rid of the undesirable aspect of the band whilst holding onto the well-behaved ones who are providing their current entertainment. The most chilling thing is that we never learn what happens to Wesley - he drops out of the story and is never heard from again.

***

That segues well with my first observation about the series: that it isn’t about the jazz band so much as it is the impact that the jazz band has on white society. This is most evident in the case of Janet Montgomery’s character Sarah, though it’s difficult to pinpoint just how self-aware Poliakoff is about what he’s done with her. I get the feeling that he may think of her as an unprejudiced, liberal, understanding white woman, and is completely oblivious to the fact that there are several scenes in which she comes across as utterly clueless and self-satisfied instead, demonstrating that even among those who consider themselves open-minded and progressive, interactions have to be taken with a pinch of salt.

First of all, remember in the Merlin years when there was a regular litany of reasons as to why people disliked Arthur/Guinevere? Because a. it happened too quickly, b. there was no chemistry, c. that they had nothing in common, d. that Gwen was “just a love interest” - and so on and so forth?

Well, as it turns out, all of those reasons are more applicable to Louie/Sarah. Despite the fact that we get more insight into Sarah’s background than Jessie and that Janet gets vastly more screen-time than Angel, her character is actually rather superfluous. She’s really just there to partake in a mixed-race romance with Louie and take photographs of everyone. Yet she’s often singled out as “the special one”. Unlike cold and aristocratic Pamela, Sarah makes a point of saying very early on that she’s not an aristocrat and instead only works for one, thus establishing herself as a self-made woman.

She’s also the first one to get to her feet and dance at the band’s first performance at the Imperial, and when they play a few weeks later for the prince, she’s emphasized by wearing a bright peachy-orange dress when the other women are invariably dressed in very pale or very dark dresses.

A scene in which Stanley takes Louie to meet his mother plays out exactly like the one in which Sarah introduces Louie to her father. In both cases Stanley/Sarah have a rather sly look about them as they make the introductions, knowing full well that their mother/father had no idea Louie was a black man. In both cases they neglect to tell their parent prior to the introduction who Louie really is because they derive amusement from their parents’ initial surprise and discomfort, with no regard whatsoever to how uncomfortable Louie might feel about the situation.

And one point Sarah tells Louie that because her father is a Russian and often suspected of being a Soviet, she therefore understands what he’s going through. Um, no. Just no.

Like I said, I have no idea whether Poliakoff was actually serious about this line in establishing her as sympathetic, or whether he was pointing out her utter cluelessness. That he later has her react with surprise to news of black men fighting in the war (giving her a moment of ignorance/contrition) suggests that we’re meant to take her first statement completely seriously: that a woman whose father is a Russian might actually have an inkling of what it’s like to be a black man in the 1930s. You don’t need me to tell you that how absurd that is, and on my second watch, it looks as though Chiwetel Ejiofor isn’t buying it either.

As such, the lack of real interaction between Louie and Sarah leaves open the possibility that she’s entering a relationship with him in order to prove something to herself more than because of a genuine interest in him, and I think she very much embodies the reason why the series probably would have been better if it had put more emphasis on the jazz band’s point-of-view.

If it had, the suspense and edginess would have been heightened considerably. As it is, there are several moment of tension in which we’re questioning whether the likes of Donaldson or Julian or Masterson or even Stanley are really as open-minded and supportive of the band as they seem, or whether they’re just exploiting them. But this could have been taken a step further to a scenario in which the audience was constantly questioning the cast of characters, wondering who is trustworthy, who is predatory, and who is just treating the band as a passing fad that they’ll drop as soon as something else comes up. The sense of precariousness regarding the band’s success and the threat of deportation could have been ratcheted up, as well as an extension of the minor arc that Jessie goes through in which she (rather like Wesley) lets the lavish lifestyle go to her head, and the constant risks and double-standards that they have to handle.

With this, and a little tighter editing, the audience could have been kept on their toes and constantly scrutinizing each person the band comes across. Is Donaldson really as helpful as he seems? Is Stanley’s interest in the band political or altruistic? Will the hotel manager treat them fairly or will he throw them over the first chance he gets? Is Sarah genuinely interested in Louie, or is this just a way to annoy her father? Is Lady Cremone truly fond of jazz or just looking for a fleeting diversion?

Sadly, it’s not that subtle. Although some white characters (Julian and Masterson) certainly have large question marks over their heads, there’s very little ambiguity concerning the goodwill of the rest of them. They treat the band with total respect and generosity, and though I concede that that may change in the final two episodes when dire circumstances finally put everyone to the test, I’m not in too much suspense over who will pull through for Louie and who will fail him. Because the series is filmed mainly from the standpoint of the white characters observing the black jazz band rather than black jazz band trying to negotiate the murky waters of the white upper-class, we already know where everyone stands in relation to them.

And with the exception of Louie, and to a lesser extent Wesley, you never really get inside any of the band members’ heads. Carla and Jessie are charming, and there is something of a deconstruction of Jessie’s role as the ingénue, but they are otherwise simply the singers and a plot-required stabbing victim. We get more insight into Sarah’s interest in photography and Pamela’s poor little rich girl background than Jessie and Carla’s friendship and ambitions.

Furthermore, nearly all the examples of racism are seen through the white character’s eyes. One particularly glaring example is when Sarah (why is it always Sarah?) is told a story by Louie about how he once brushed against a woman’s dinner table and witnessed her demanding that her cutlery be changed. Later at the Imperial, Jessie is walking through the foyer when her hand accidentally brushes against an old woman’s teacup - who sure enough, asks a waiter to get her a replacement. But here’s the thing: Jessie doesn’t notice. Sarah does. It is Sarah’s reaction that the camera focuses on; her discomfort and disgust at the old woman’s behaviour, while Jessie remains completely oblivious.

And perhaps I’m reaching here, but I felt it was interesting that the narrative gives Stanley a stake in the band’s success. He’s told numerous times that if they’re not successful, then he’ll pay with his job/credibility, leading to the implication that it’s not enough that just the band is dancing on the edge - Stanley’s career is riding on it too.

But if none of that convinces you, then a look at the closing credits demonstrates that the band members are considered interchangeable with their instruments. They don’t get names; they’re identified and credited solely by the instruments they play.

***

Okay, I suppose I better talk about the fact that four Merlin stars feature in this series; not only regulars Angel Coulby and Anthony Head, but also guest-stars Janet Montgomery and John Hopkins (who played Sir Oswald in Gwaine). Now, you should know by now about my disappointment surrounding Princess Mithian’s return to the show in series 5 and the complete lack of interaction she had with Queen Guinevere. That these two actresses would be appearing together in a completely unrelated project felt like lightening striking twice. Surely, if I was denied interaction between them in Merlin, I could look forward to seeing them together in Dancing on the Edge.

Nope.

They barely interact. They’re in a couple of scenes together, but they never speak to each other. That is, Sarah DOES actually speak to Jessie, but the latter is already in her coma at the time and so naturally can’t respond. Even more annoyingly, there’s an earlier scene in which Sarah tells the others that she helped Jessie and Carla chose their dresses for the evening - but we don’t actually get to see this happening.

Sigh. I don’t think lightening will strike a third time. As it is, Sarah/Jessie feels like an odd inversion of Guinevere/Mithian. On Merlin, Guinevere was the main character of huge importance who still got very little screen-time, whilst Mithian was the adored princess whom everyone loved that nonetheless had no real purpose beyond being rejected. Here Jessie is the star performer who gets everyone’s love and attention and yet is abruptly removed from the narrative at the apex of her story, whilst Sarah is ostensibly the female lead who gets a lot of screen-time whilst nevertheless being a bit redundant.

There is also some rather bizarre role association confusion going on when Donaldson (that is, Anthony Head) tries to gently coax Jessie out of her coma by talking to her about her singing voice and reminding her of her experiences at a recent garden party, calling her a “dear girl” and tenderly willing her back to life. It actually works. King Uther urging Queen Guinevere back to life. Who’d have thought?

There’s another scene that made me smile, in which Stanley says that he was working on a screenplay about King Arthur, as well as Angel being given the line: “the son of the king?!” when she sees the approach of the Prince of Wales/Sir Oswald. I highly doubt either one was deliberate, but it was still a cute coincidence.

***

Keep in mind, these are just my thoughts on the first three episodes of the series. There are still two more to go, and perhaps they will justify some of Poliakoff’s decisions that I’ve criticized here. Perhaps he’s got something really clever and subversive up his sleeve, and if so, I’ll make amendments in my next post.

It would appear that the rest of the show will deal with the mystery of who killed Jessie: my money is on Julian simply because there appear to be no other suspects, though motivation is a little hazy. Perhaps something to do with the freemasons? And how he managed to make it to Paris despite Louie seeing him late at the hotel will need to be explained.

But look at it this way - clearly Angel had a great time filming this show. On a final note, listen to this interview she did for a radio station. It’s really worth it for the excited fan-girling of the interviewer, who sounds genuinely excited to be talking to her, and raves about her singing voice. It’s really quite sweet.