More than kisses, letters mingle souls - for rthstewart

Title: More than kisses, letters mingle souls

Author: athousandwinds

Recipient: rthstewart

Rating: PG

Possible Spoilers/Warnings: The Magician's Nephew

Summary: Digory comes home from the war, but Polly is still fighting hers.

Mother was gratifyingly pleased to see him, and wept on his shoulder as if he'd been sent home with a hole in it. Aunt Letty was more measured, though she viewed Digory's commendation with a great deal of pleasure and no little smugness. Digory did not mind this from her because, all truth be told, in the most frightened moment of his life (which had been recent, and very frightening indeed) he had pictured Aunt Letty on what he thought must have been the most terrifying day in her life and had aspired to only half her self-possession. He did mind it from Uncle Andrew, who seemed to credit Digory's bravery to his own account and this was only true in the most indirect way. He did not say anything about this, though, because he had been away from home for such a very long time and when you have been away that long you don't quite like to quarrel on your first day back.

"Hmph," said Uncle Andrew, several times. "He gets that bravery from our side, Mabel!" And it was quite clear that Uncle Andrew really meant that Digory got his bravery from him.

Although Digory would have liked to go on talking about how brave he had been for some time, he knew that this would only make him look big-headed, and, besides, Uncle Andrew was spoiling it a bit. So instead he asked - and, in all fairness, he really did want to know - how Polly was. "Miss Plummer, I mean," he added hurriedly, for although Polly was almost as old as he was and they had known each other for two thirds of their lives, it was still rude in those days to call a lady by her Christian name. But Mother only smiled at him with a hopeful edge and said that Polly was very well and if Digory went to her house in a few weeks she would probably be very glad to see him.

Now, Digory was disappointed by this, for he and Polly had been very close for many years, even though she had been Head Girl at her school and he had not been disliked at his, and both of them might well have found other, more congenial companions. But Digory had travelled the wide world - that is to say, England and what little of France that could be seen from the midst of a marching column - and not found one person he liked more than Polly, even when they were quarrelling (and they had had several very bad quarrels in the years they had known each other). So you must understand that he was much nettled by the prospect of waiting more than a month to see his greatest friend, when he had only just come home from the war (and with a commendation!).

"Well, I call that nice feeling," he said, rather rudely. "Is she ill?" It seemed the most likely explanation for her conduct, for he was unwilling to think too badly of her. But his mother passed a glance with Aunt Letty over his head, which Digory, no longer twelve years old, easily recognised. "What's wrong?"

"Ill, yes," said Mother, but Aunt Letty overrode her. Aunt Letty was very good at this, as you likely will be should you ever become a maiden aunt.

"Don't be a fool, Mabel," she said. "Well, he will likely find out some other way and he needn't trouble himself to. Polly Plummer is in Holloway Prison, and good for her."

This somewhat surprising conclusion was in fact not at all difficult for Digory to understand. "I thought she'd given all that up," he said.

"So she might have," said Aunt Letty, "except that she felt that the bargain Mrs Fawcett got for us was not quite fair and I for one do not blame her." As she said this, she looked formidable, and had Mrs Fawcett been in the room she might have quailed. Digory considered for the first time that the new Act might have been pretty rotten for Aunt Letty, too, for despite her advanced age - and it was so advanced that he was not allowed to know it - she was still not entitled to vote, whereas Uncle Andrew was. Seeing it in these terms made him so very sympathetic to the cause of women's suffrage that he resolved to visit Polly in prison and see if he could do anything for her. What that might be, he had only a vague idea, short of helping her escape, and he would have thought Polly a poor sportswoman if she had tried it.

In the event, she did not want anything. She was only sentenced to a month and a half, she said, and really it was only that she'd decided against paying the fine. She did not intend a hunger strike - "Honestly, Digory, we gave that up when the war started. Why are you so stupid today?" - and as she was not the only suffragist in the prison she indeed got on very well.

"I thought you gave up violent protesting when the war started, too," Digory said, and Polly told him crossly that she had never been at all violent in her demonstrations, only waved signs and shouted a lot, and why he didn't remember all this she didn't know. Digory had always been the first person she applied to for donations to the cause (largely because at school he always had more pocket money than she did) but he had little interest in politics. This infuriated Polly, but twenty years of experience had taught her that it was useless to argue with him about it.

"And anyway," she said, "it was an accident."

"What was?"

"I knocked the constable's helmet off," she said. She looked so doleful at this that Digory laughed at her, and she became annoyed with him all over again. It really was not funny to her, for they were electing a new president of the union and she could not campaign from prison.

"You are a pig, Digory Kirke," she said, and Digory did not protest this as he would have done in his salad days, for he knew that Polly was secretly fond of pigs. Cats were snobby, she'd said, and dogs frankly irritating, but you knew where you were with a pig. So his visit did not end on such a bad note as might have been supposed, and by the time Digory got off the train he felt it had been a great success.

Polly Plummer

Holloway Prison

I'm not entirely certain of the

correct address but I daresay

you can look it up, you lazy thing

21st September 1919

Dear Digory,

I wish you would speak to Miss Ketterley for me, because I don't like that letter she wrote to the Woman's Leader at all. I am not one of the new feminists, but I can't and won't ascribe ill-intention to their actions. I think some of their ideas are very good, but then I don't think more access to birth control will cause quite the plague of immorality she worries about. Eleanor Rathbone thinks it is the sort of thing that would be most useful to married women, and I agree. I am sorry to be so blunt in a letter to you, but she must be made to see that rhetoric like that can only cause a deeper rift in the movement and she will only become angry with me. You're her nephew, she can't refuse to speak to you ever again.

I don't really understand why any of this is happening, except that we have won such a great victory that no one is sure where to go next. And that some of the people in NUSEC think that we should go back to fundamentals, and focus on women's needs, only frankly I don't think we mean the same thing by it, because they seem to be under the odd impression that women are really quite peaceful and maternal by nature and, well, you and I both know that there is at least one woman of our acquaintance who was neither. (And while I'm very peaceful, I don't think I'm very maternal, but perhaps that's something that comes upon you suddenly with age.)

Regarding your last letter, no, I don't think of marriage. What a stupid question! I admit that I used to wish I had a husband, if only so that I could wave him around whenever someone said - with that horrible smug look, you know - that all of us were frustrated spinsters. But that was years ago. You're the only man I can think of marrying, and if it's all the same to you I'd rather not. The whole business just seems terribly awkward. That's why you mentioned it, isn't it? Your mother wants you to get married and courting anyone else would be too much of a bother. You forget I know you, Digory Kirke.

By the by, I get out next week, so please, if you're not busy, come over for tea and we can talk properly. I want to know about that job at the university, it seems like just the thing for you.

Yours faithfully sincerely oh I can never remember anyway and I don't care

Polly

"Do you ever think about it?" Digory asked.

"Think about what?"

Polly was looking into her teacup when she said it, though, and her face was a little - just a little - paler than usual. Digory was momentarily torn. He did not want to push, for he despised it when people pushed him, and, besides, pushing women sometimes made them cry, which of all things he wished to avoid. But at the same time he did really want to know. So he said, "Narnia. And - and all that."

"Sometimes," Polly said, and by "sometimes" she clearly meant "often". Digory understood that. He thought of Narnia often, too, for it was impossible not to.

"Yes," he said eloquently. Polly gave him a look over the rim of her cup, which she was using to hide her face. This was silly, Digory thought, for he could see her eyes perfectly, and he told her so.

"Excuse me," Polly said, firing up, "if I don't particularly want to share all my private thoughts, especially not with you."

"Oh, and what's wrong with me, exactly," demanded Digory, and unfortunately for Polly's teacup and indeed the rest of the Wedgwood set, she informed him. I am ashamed to say that their quarrel was better suited to children than people of some thirty years, and Digory at least nearly stormed out, only to recall at the last moment that he might well encounter one of the other Plummers in the hall and have to explain himself. It was only after Polly had stuffed a jammy scone down the back of his shirt and he had retaliated with the contents of the sugar bowl that they reconciled. They sat on the carpet and Polly sent up a prayer of thankfulness that they had not attracted the attention of her strict mother.

"Would you have liked to have stayed in Narnia?" Digory asked somewhat diffidently. He was rather afraid that the answer was yes. Polly had never seemed to like England all that much.

"No," said Polly. "Well, a bit. When I get very angry, you know, and I think, oh, why didn't I stay in Narnia and become a princess. But I prefer it here." She grinned at Digory as she said this, and he felt like a conspirator when he grinned back. "I'd miss my family and London and arguing with people in NUSEC - you've no idea how mad you can get at people who agree with you on everything but one thing."

"Hmmm," Digory said. It was, with some editing, more or less how he felt about the matter and this relieved him in some obscure way. In an awkward attempt to inject some romance into the conversation, he added, "I'd miss you, too."

Polly looked at him. Digory, with the self-consciousness of impending humiliation, felt the sticky scone begin to work its way slowly down his spine.

"Well, I suppose," she said. "Digory."

"I don't want to," Digory said, and then, "I mean, I do want to," and then, "It's not all the same to me," and then, to finish off, "I'm sorry." It seemed like the only thing left to say that might take that miserable look off Polly's face.

"I said, Digory," Polly began, and then, miraculously, she added, "It's not that," and seemed to waver, and then, "You just had to, didn't you," and finally, "It's me, not you," in such a wretched tone that it was the second-worst thing anybody had ever said to Digory, and the first-worst had been Aslan, telling him that he'd brought evil into Narnia.

They stared at each other.

"I've written an article for Time and Tide," Polly said, all in a rush. "Would you like to read it?"

"Yes, of course," said Digory, who had never wanted to read an article about universal suffrage less. Polly fled upstairs and he heaved a sigh of relief before trying to scrape sugar out of the pomade in his hair and rescuing the scone from where it had ended up in his trousers.

"Sorry I took so long," Polly said, bursting into the parlour. She'd seized the opportunity to brush her hair again and dust off her dress. She handed him a sheet of typewritten foolscap and removed the scone he was eating kindly but firmly from his fingers. "I can't believe you actually ate that," she said. She seemed to feel much better about refusing his not-exactly-a-proposal now.

"I didn't finish it," said Digory, as if this were some sort of defence.

"Impossible," said Polly, and Digory shrugged. This phlegmatic response apparently removed the last of her embarrassment, for she threw it on the fire, and then they talked about Oxford until dinner time.

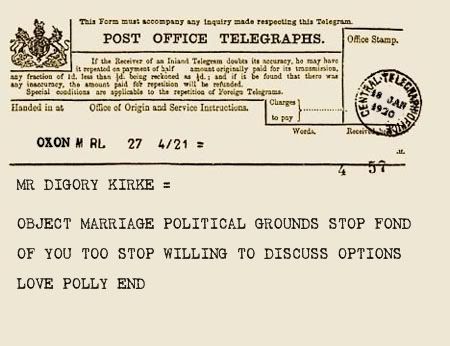

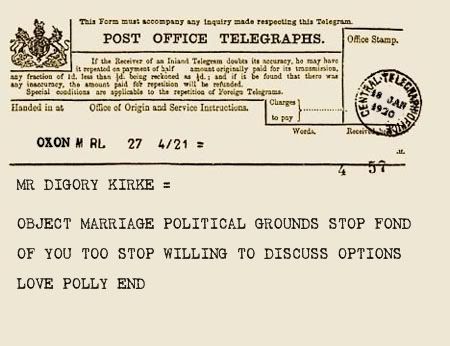

Digory Kirke

c/o Wadham College

Parks Road

Oxford

16th January 1920

Dear Polly,

Re: Aunt Letty, no, I did not ask. The thing about aunts (and you may know everything but you don't know this, for you have none) is that they are like mothers but aren't liable to forgive you for things that are quite dreadful. You should write to her yourself. I suspect that she likes you better.

Re: your article, it looks very well in print. I have subscribed to the magazine, even though they had the bad taste to publish you.

Re: our discussion of October last, I don't like your implication that I proposed as a last resort. I share your sentiments regarding choice of spouse: you are the first, last and only person I could ever contemplate marrying. I hope I have clarified the situation for you.

Re: the obscene number of telegrams you have sent me, I realise that you are delighting in earning your own income. Please spend it on something else. Whenever I receive a telegram I always assume something terrible has happened.

Yours,

Digory

P. S. I hate writing letters, you know that. When are you coming up?

Historical notes: The 1918 Representation of the People Act granted universal male suffrage, but only women over thirty who either were or were married to the owner of a household were granted the right to vote. Millicent Garrett Fawcett, a leading suffragist, had been instrumental in the negotiations for the Act and was the focus of much anger among the suffrage movement at what was seen as betrayal by middle-class married suffragists. Nevertheless, after this point British feminism went into a rapid decline, not helped by a deep ideological rift in the movement. The two periodicals Polly mentions were real, though the timeline of their production is fudged. Lewis himself was a contributor to Time and Tide for some years.

Original Prompt:

What I want: Any of the following (Pick one, pick all!): UST; Witty banter and snark; Politics, finance or military strategy; World War 2; Worldbuilding; Gap-filling; Culture clash (within Narnia or Narnia vs. Spare Oom); healthy, normal, romantic relationship between consenting adults (canon pairing or OC); someone being extraordinarily clever and getting out of a jam.

Prompt words/objects/quotes/whatever:

"The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it."

"Sex and religion are closer to each other than either might prefer."

"Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake."

"His ignorance is encyclopedic."

"Forgive your enemies, but never forget their names."

"I am fond of pigs. Dogs look up to us. Cats look down on us. Pigs treat us as equals."

What I definitely don't want in my fic: m/m; excessive angst, gore or violence; any non-con whatsoever (Rilian & Lady of the Green Kirtle (OK); Susan "Fallen Away From Narnia because of Lipstick and Nylons" or excessive focus upon the word "Impossible" or Caspian; Lucy sidelined or being protected by her overbearing big brothers and worry wort sister

Author: athousandwinds

Recipient: rthstewart

Rating: PG

Possible Spoilers/Warnings: The Magician's Nephew

Summary: Digory comes home from the war, but Polly is still fighting hers.

Mother was gratifyingly pleased to see him, and wept on his shoulder as if he'd been sent home with a hole in it. Aunt Letty was more measured, though she viewed Digory's commendation with a great deal of pleasure and no little smugness. Digory did not mind this from her because, all truth be told, in the most frightened moment of his life (which had been recent, and very frightening indeed) he had pictured Aunt Letty on what he thought must have been the most terrifying day in her life and had aspired to only half her self-possession. He did mind it from Uncle Andrew, who seemed to credit Digory's bravery to his own account and this was only true in the most indirect way. He did not say anything about this, though, because he had been away from home for such a very long time and when you have been away that long you don't quite like to quarrel on your first day back.

"Hmph," said Uncle Andrew, several times. "He gets that bravery from our side, Mabel!" And it was quite clear that Uncle Andrew really meant that Digory got his bravery from him.

Although Digory would have liked to go on talking about how brave he had been for some time, he knew that this would only make him look big-headed, and, besides, Uncle Andrew was spoiling it a bit. So instead he asked - and, in all fairness, he really did want to know - how Polly was. "Miss Plummer, I mean," he added hurriedly, for although Polly was almost as old as he was and they had known each other for two thirds of their lives, it was still rude in those days to call a lady by her Christian name. But Mother only smiled at him with a hopeful edge and said that Polly was very well and if Digory went to her house in a few weeks she would probably be very glad to see him.

Now, Digory was disappointed by this, for he and Polly had been very close for many years, even though she had been Head Girl at her school and he had not been disliked at his, and both of them might well have found other, more congenial companions. But Digory had travelled the wide world - that is to say, England and what little of France that could be seen from the midst of a marching column - and not found one person he liked more than Polly, even when they were quarrelling (and they had had several very bad quarrels in the years they had known each other). So you must understand that he was much nettled by the prospect of waiting more than a month to see his greatest friend, when he had only just come home from the war (and with a commendation!).

"Well, I call that nice feeling," he said, rather rudely. "Is she ill?" It seemed the most likely explanation for her conduct, for he was unwilling to think too badly of her. But his mother passed a glance with Aunt Letty over his head, which Digory, no longer twelve years old, easily recognised. "What's wrong?"

"Ill, yes," said Mother, but Aunt Letty overrode her. Aunt Letty was very good at this, as you likely will be should you ever become a maiden aunt.

"Don't be a fool, Mabel," she said. "Well, he will likely find out some other way and he needn't trouble himself to. Polly Plummer is in Holloway Prison, and good for her."

This somewhat surprising conclusion was in fact not at all difficult for Digory to understand. "I thought she'd given all that up," he said.

"So she might have," said Aunt Letty, "except that she felt that the bargain Mrs Fawcett got for us was not quite fair and I for one do not blame her." As she said this, she looked formidable, and had Mrs Fawcett been in the room she might have quailed. Digory considered for the first time that the new Act might have been pretty rotten for Aunt Letty, too, for despite her advanced age - and it was so advanced that he was not allowed to know it - she was still not entitled to vote, whereas Uncle Andrew was. Seeing it in these terms made him so very sympathetic to the cause of women's suffrage that he resolved to visit Polly in prison and see if he could do anything for her. What that might be, he had only a vague idea, short of helping her escape, and he would have thought Polly a poor sportswoman if she had tried it.

In the event, she did not want anything. She was only sentenced to a month and a half, she said, and really it was only that she'd decided against paying the fine. She did not intend a hunger strike - "Honestly, Digory, we gave that up when the war started. Why are you so stupid today?" - and as she was not the only suffragist in the prison she indeed got on very well.

"I thought you gave up violent protesting when the war started, too," Digory said, and Polly told him crossly that she had never been at all violent in her demonstrations, only waved signs and shouted a lot, and why he didn't remember all this she didn't know. Digory had always been the first person she applied to for donations to the cause (largely because at school he always had more pocket money than she did) but he had little interest in politics. This infuriated Polly, but twenty years of experience had taught her that it was useless to argue with him about it.

"And anyway," she said, "it was an accident."

"What was?"

"I knocked the constable's helmet off," she said. She looked so doleful at this that Digory laughed at her, and she became annoyed with him all over again. It really was not funny to her, for they were electing a new president of the union and she could not campaign from prison.

"You are a pig, Digory Kirke," she said, and Digory did not protest this as he would have done in his salad days, for he knew that Polly was secretly fond of pigs. Cats were snobby, she'd said, and dogs frankly irritating, but you knew where you were with a pig. So his visit did not end on such a bad note as might have been supposed, and by the time Digory got off the train he felt it had been a great success.

Polly Plummer

Holloway Prison

I'm not entirely certain of the

correct address but I daresay

you can look it up, you lazy thing

21st September 1919

Dear Digory,

I wish you would speak to Miss Ketterley for me, because I don't like that letter she wrote to the Woman's Leader at all. I am not one of the new feminists, but I can't and won't ascribe ill-intention to their actions. I think some of their ideas are very good, but then I don't think more access to birth control will cause quite the plague of immorality she worries about. Eleanor Rathbone thinks it is the sort of thing that would be most useful to married women, and I agree. I am sorry to be so blunt in a letter to you, but she must be made to see that rhetoric like that can only cause a deeper rift in the movement and she will only become angry with me. You're her nephew, she can't refuse to speak to you ever again.

I don't really understand why any of this is happening, except that we have won such a great victory that no one is sure where to go next. And that some of the people in NUSEC think that we should go back to fundamentals, and focus on women's needs, only frankly I don't think we mean the same thing by it, because they seem to be under the odd impression that women are really quite peaceful and maternal by nature and, well, you and I both know that there is at least one woman of our acquaintance who was neither. (And while I'm very peaceful, I don't think I'm very maternal, but perhaps that's something that comes upon you suddenly with age.)

Regarding your last letter, no, I don't think of marriage. What a stupid question! I admit that I used to wish I had a husband, if only so that I could wave him around whenever someone said - with that horrible smug look, you know - that all of us were frustrated spinsters. But that was years ago. You're the only man I can think of marrying, and if it's all the same to you I'd rather not. The whole business just seems terribly awkward. That's why you mentioned it, isn't it? Your mother wants you to get married and courting anyone else would be too much of a bother. You forget I know you, Digory Kirke.

By the by, I get out next week, so please, if you're not busy, come over for tea and we can talk properly. I want to know about that job at the university, it seems like just the thing for you.

Yours faithfully sincerely oh I can never remember anyway and I don't care

Polly

"Do you ever think about it?" Digory asked.

"Think about what?"

Polly was looking into her teacup when she said it, though, and her face was a little - just a little - paler than usual. Digory was momentarily torn. He did not want to push, for he despised it when people pushed him, and, besides, pushing women sometimes made them cry, which of all things he wished to avoid. But at the same time he did really want to know. So he said, "Narnia. And - and all that."

"Sometimes," Polly said, and by "sometimes" she clearly meant "often". Digory understood that. He thought of Narnia often, too, for it was impossible not to.

"Yes," he said eloquently. Polly gave him a look over the rim of her cup, which she was using to hide her face. This was silly, Digory thought, for he could see her eyes perfectly, and he told her so.

"Excuse me," Polly said, firing up, "if I don't particularly want to share all my private thoughts, especially not with you."

"Oh, and what's wrong with me, exactly," demanded Digory, and unfortunately for Polly's teacup and indeed the rest of the Wedgwood set, she informed him. I am ashamed to say that their quarrel was better suited to children than people of some thirty years, and Digory at least nearly stormed out, only to recall at the last moment that he might well encounter one of the other Plummers in the hall and have to explain himself. It was only after Polly had stuffed a jammy scone down the back of his shirt and he had retaliated with the contents of the sugar bowl that they reconciled. They sat on the carpet and Polly sent up a prayer of thankfulness that they had not attracted the attention of her strict mother.

"Would you have liked to have stayed in Narnia?" Digory asked somewhat diffidently. He was rather afraid that the answer was yes. Polly had never seemed to like England all that much.

"No," said Polly. "Well, a bit. When I get very angry, you know, and I think, oh, why didn't I stay in Narnia and become a princess. But I prefer it here." She grinned at Digory as she said this, and he felt like a conspirator when he grinned back. "I'd miss my family and London and arguing with people in NUSEC - you've no idea how mad you can get at people who agree with you on everything but one thing."

"Hmmm," Digory said. It was, with some editing, more or less how he felt about the matter and this relieved him in some obscure way. In an awkward attempt to inject some romance into the conversation, he added, "I'd miss you, too."

Polly looked at him. Digory, with the self-consciousness of impending humiliation, felt the sticky scone begin to work its way slowly down his spine.

"Well, I suppose," she said. "Digory."

"I don't want to," Digory said, and then, "I mean, I do want to," and then, "It's not all the same to me," and then, to finish off, "I'm sorry." It seemed like the only thing left to say that might take that miserable look off Polly's face.

"I said, Digory," Polly began, and then, miraculously, she added, "It's not that," and seemed to waver, and then, "You just had to, didn't you," and finally, "It's me, not you," in such a wretched tone that it was the second-worst thing anybody had ever said to Digory, and the first-worst had been Aslan, telling him that he'd brought evil into Narnia.

They stared at each other.

"I've written an article for Time and Tide," Polly said, all in a rush. "Would you like to read it?"

"Yes, of course," said Digory, who had never wanted to read an article about universal suffrage less. Polly fled upstairs and he heaved a sigh of relief before trying to scrape sugar out of the pomade in his hair and rescuing the scone from where it had ended up in his trousers.

"Sorry I took so long," Polly said, bursting into the parlour. She'd seized the opportunity to brush her hair again and dust off her dress. She handed him a sheet of typewritten foolscap and removed the scone he was eating kindly but firmly from his fingers. "I can't believe you actually ate that," she said. She seemed to feel much better about refusing his not-exactly-a-proposal now.

"I didn't finish it," said Digory, as if this were some sort of defence.

"Impossible," said Polly, and Digory shrugged. This phlegmatic response apparently removed the last of her embarrassment, for she threw it on the fire, and then they talked about Oxford until dinner time.

Digory Kirke

c/o Wadham College

Parks Road

Oxford

16th January 1920

Dear Polly,

Re: Aunt Letty, no, I did not ask. The thing about aunts (and you may know everything but you don't know this, for you have none) is that they are like mothers but aren't liable to forgive you for things that are quite dreadful. You should write to her yourself. I suspect that she likes you better.

Re: your article, it looks very well in print. I have subscribed to the magazine, even though they had the bad taste to publish you.

Re: our discussion of October last, I don't like your implication that I proposed as a last resort. I share your sentiments regarding choice of spouse: you are the first, last and only person I could ever contemplate marrying. I hope I have clarified the situation for you.

Re: the obscene number of telegrams you have sent me, I realise that you are delighting in earning your own income. Please spend it on something else. Whenever I receive a telegram I always assume something terrible has happened.

Yours,

Digory

P. S. I hate writing letters, you know that. When are you coming up?

Historical notes: The 1918 Representation of the People Act granted universal male suffrage, but only women over thirty who either were or were married to the owner of a household were granted the right to vote. Millicent Garrett Fawcett, a leading suffragist, had been instrumental in the negotiations for the Act and was the focus of much anger among the suffrage movement at what was seen as betrayal by middle-class married suffragists. Nevertheless, after this point British feminism went into a rapid decline, not helped by a deep ideological rift in the movement. The two periodicals Polly mentions were real, though the timeline of their production is fudged. Lewis himself was a contributor to Time and Tide for some years.

Original Prompt:

What I want: Any of the following (Pick one, pick all!): UST; Witty banter and snark; Politics, finance or military strategy; World War 2; Worldbuilding; Gap-filling; Culture clash (within Narnia or Narnia vs. Spare Oom); healthy, normal, romantic relationship between consenting adults (canon pairing or OC); someone being extraordinarily clever and getting out of a jam.

Prompt words/objects/quotes/whatever:

"The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it."

"Sex and religion are closer to each other than either might prefer."

"Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake."

"His ignorance is encyclopedic."

"Forgive your enemies, but never forget their names."

"I am fond of pigs. Dogs look up to us. Cats look down on us. Pigs treat us as equals."

What I definitely don't want in my fic: m/m; excessive angst, gore or violence; any non-con whatsoever (Rilian & Lady of the Green Kirtle (OK); Susan "Fallen Away From Narnia because of Lipstick and Nylons" or excessive focus upon the word "Impossible" or Caspian; Lucy sidelined or being protected by her overbearing big brothers and worry wort sister