THE ICON:TRUTH AND FABLES - Chapter 6 - Iconographic canonicity

And now, finally, we can pass from what is unimportant and secondary and even non-existent and invented - but still considered by certain persons to be of primary importance - in the artistic language of icons to that which is characteristic and important, and certainly needs to be included in the definition of icons.First of all, any icon needs to be canonical. So what does "being canonical" really mean?

The simple translation of the Greek does not help: "canonical" describes something that is regular, according to the rule. And indeed, how do we establish which icons are regular or "true" according all their different characteristics? In current practice, the term "canonical icon" has a very specific meaning: it is an icon that conforms with the iconographic canon, a concept not to be confused with the style, as poorly instructed people often do.

Canon and style - these concepts are so different that one and the same icon can be flawless in its iconography (i.e. canonicity) and totally unacceptable in terms of style. Conversely, the iconography may be archaic, and style excellent (as happens when artists from the capital are invited to the provinces, where person commissioning their work are unfamiliar with the latest themes and compositional findings). Conversely, the style may be archaic, and iconography highly developed (this happens when a theologian from the capital orders a work from a local self-taught artisan). The iconography can be "western" and the style "eastern" (the most striking example being the Sicilian Catholic churches of the twelfth century).

Or the other way round, the iconography can be "oriental" and the style "western" (examples abound, especially Athonite and Russian icons of the Theotokos from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, which often retain the traditional "Byzantine" typology).

And finally, a style that is impeccable in its style may prove uncanonical: for example, the icons of Old Testament trinity with the cross halo on one of the angels. Here the uncanonical iconography is easily fixed by removing the cross on the nimbus. However, the stylistic mismatch of the icon with the truth of the Church not infrequently results in a situation that can be fixed only by repainting the icon in another, acceptable style, i.e. by destroying the original image. We shall discuss below what is acceptable and unacceptable style, but in the present chapter the subject of our attention will be the iconographic canon.

Первая половина 15 в., ГРМ

The iconographic canon is the outline, or pattern, or "scheme" of a subject that is theologically well-founded. In other words, which persons and objects need to be included in the presentation, how do they inter-relate, and what clothing and postures should they have. This canon can be represented by a simplified technical drawing, or even by a text alone.

Should we then assume that there are collections of such patterns; approved and promoted by a supreme body of ecclesiastical power (like, for example, a council) as was the case when defining the texts of the New Testament canon? Such collections exist, known in Russian as podlinnik, derived from the old Russian word "podlinnii" meaning "true". The oldest of these collections date from the eleventh century in Greece and the sixteenth century in Russia. The drawings (prorissi) and descriptive text of which they are composed have been gathered from existing icons. These podlinnik known in some twenty different redactions, that of Sophia, of Siiski, Stroganov, Pomorie, the Leaves of Kiev, and a host of others, with the quality and precision of the descriptions improving over time. Not one of these redactions is complete.

Their instructions vary from one redaction to another, with comments at times including criticisms such as: "That is quite incorrect, because he (the writer is talking about St. Theodore of Pamphylia, presented as an old man, dressed as a bishop) was still young when he suffered martyrdom for Christ, and was never a bishop.”[1] "Or even blunter: "Stupid iconographers have taken to representing quite incorrectly the holy martyr Christopher with a dog's head ... which is nonsense."

[1] Quoted by Theodore Bouslaieff, Подлинник по редакции XVIII века in Богословие образа. Икона и иконописцы. Антология under edited by of A .N. Strijov, Moscow, 2002, p. 242.

But we should not dwell excessively on the contradictions and nonsense in the podlinnik: much more important is the fact that they are first and foremost practical manuals for artists, and as such do not have the normative and binding force of ecclesiastical documents. The Church has never desired to freeze its artists' creativity of artists through constraining decisions. The Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II (787), meeting in response to iconoclasm and prescribing the creation of sacred images, neither established or commissioned any normative collection which would have limited the permitted representations, not more than did the Russian Councils of the Hundred Chapters (1555) and Moscow (1666-1667). On the contrary, from the start, while inviting artists to follow recognized models, the council had already anticipated the possibility of the enlargement and change of the canon. It is precisely in expectation of this enlargement, not so as to restrict it, that the Council of Nicaea II called for a stronger sense of responsibility, entrusting this responsibility to the senior hierarchy of the Church.

In 787, it was of course technically impossible to create and disseminate a normative collection of iconographic patterns, but it is noteworthy that such an exercise has never been undertaken by the Church. The only existing collections are, as we have said, simple practical manuals for artists, in no ways emanating from the Church hierarchy. Neither the Council of the Hundred Chapters in 1551 nor the Grand Council of Moscow of 1666-7, both vital councils in the history of Russian iconography, established any normative document, either by consecrating an existing podlinnik or by reference to some of the best-known icons. Engravings and printed books were already very widespread in Russia, and every iconographic workshop had its own larger or smaller stock of model drawings. But no one found it necessary to sort, systematize and edit them.

It is true that even serious books cite a truncated extract from the Deeds of the Council of the Hundred Chapters supposedly prescribing that "artists should paint icons according to ancient models, such the Greek artists use to and still paint them. Let them paint as Rublev painted". These two sentences are presented incorrectly as a prescription requiring artists to ever copy the works of the early painters, and particularly those of Andrei Rublev. It is important to point here to an unfortunate mistake, and a certain persistence in ignorance, due to the way this quotation has been truncated and taken out of its context. Let us complete it: "as Rublev and other famous iconographers painted, let them sign the works "Holy Trinity", and let them not change anything with their own imagination (that of the artists)."

Let us not be held up by the various interpretations of terms such as "painted and paint" or "other famous iconographers." Let us simply point out that this quote is not an authoritative decision to mark out the path for the entire future development of Russian iconography, but that it constitutes simply the response (and not just part of it) to the question Ivan IV had put to the Council: "Should we, in the icons of the Holy Trinity, place the cruciferous nimbuses on all three angels? Or should we place a nimbus only on the central angel, and marking it with the name of Christ?”[1]

By falsifying the texts in this way, either intentionally or in ignorance, these authors have maintained the unfounded myth of a certain canon established in writing by the Church at a particular point in time. Notably, though, these authors fail to define this canon, even if, according to their writings, deviating only one step to the left or right is enough to hurl one into the abyss of heresy. The stage is set for iconographic witchhunts!

Before emitting any judgements on canonicity, it is especially important to realize that in fact neither the time of the Undivided Church or in Eastern Orthodoxy have there existed, and until today there still do not exist, any rules or any document that regulate and stabilize the iconographic canon. Simply, the iconography of the Church has developed continuously over two millennia, in a regime of informal self-regulation, with the best advances retained, and the less successful ones left to wither on the vine, but without vociferous condemnations. There has been a constant search for novelty, not for novelty’s sake, but above all for the greater glory of God, and often in the process resurrecting additions to the canon disregarded in earlier times.

Here are some examples of changes in the iconographic canon over the centuries. This presentation is by no means exhaustive, it is intended only to open the eyes of Westerners convinced of the frozen and binding nature of the iconographic canons.

- The Annunciation. This iconographic subject has been around since the 3rd century, and already from this time with three variants (Mary at the well, Mary spinning, and Mary reading). Archangel Gabriel gained wings only between the fifth and sixth centuries.

[1] Deeds of the Council of Hundred Chapters, chap. 41, issue 1.

Фреска катакомб Присциллы, Рим, 3 в.

In the eighth century there appeared at Nicaea the variant "Annunciation with the child in the womb," which would remain unique in its kind for a long time, until resurrected in Russia in the twelfth century, but becoming popular only in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, only then to disappear almost completely.

"Устюжское Благовещение" 12 в.

- The Epiphany (Baptism of Christ). The earliest images of the Baptism of Christ (fourth - fifth centuries) show a beardless Christ, naked, fully frontal, with the waters of Jordan's covering him up to the shoulder. Often included in the composition is the figure of the prophet Isaiah, who had prophesied the Epiphany. The angels holding cloths appear only in the eleventh century. The perizonium (loincloth) of Christ, who is immersed only to the ankles, appears in the twelfth century, and at this point too St. John the Baptist starts to be clothed with a hair shirt, rather than a tunic and chiton. It is from this time also, that we find images of Christ in three-quarters profile, turned to John, and covering his genitals with his hand.

Равенна, Арианский баптистерий, 5 в.

Мюстайр (Швейцария), 800 г.

-Christ. In the early centuries, we identify three different types in the iconography of the Savior: the Syrian type (black hair with an oriental type face), Roman (with a beard divided in two and blond hair), and finally a beardless youth (especially in the miracle scenes).

Нерези

Арль, Археологический музей, 4 в.

Лондон, Музей Виктории и Альберта, 8 в.

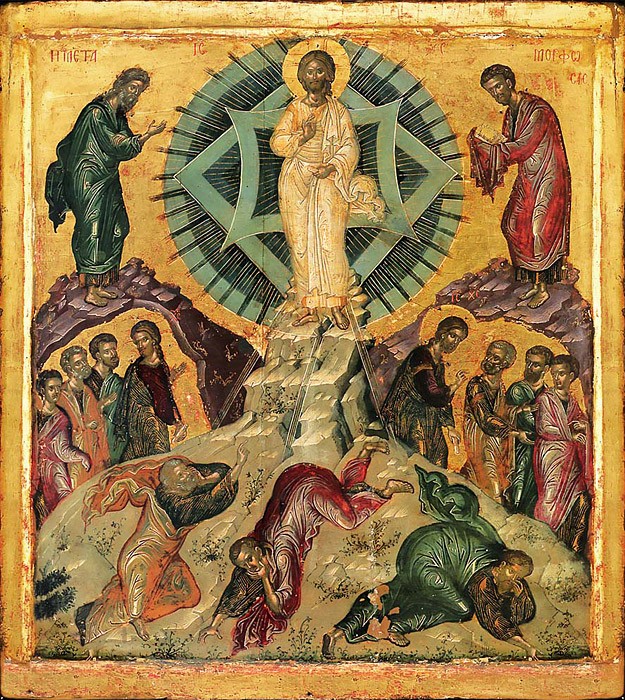

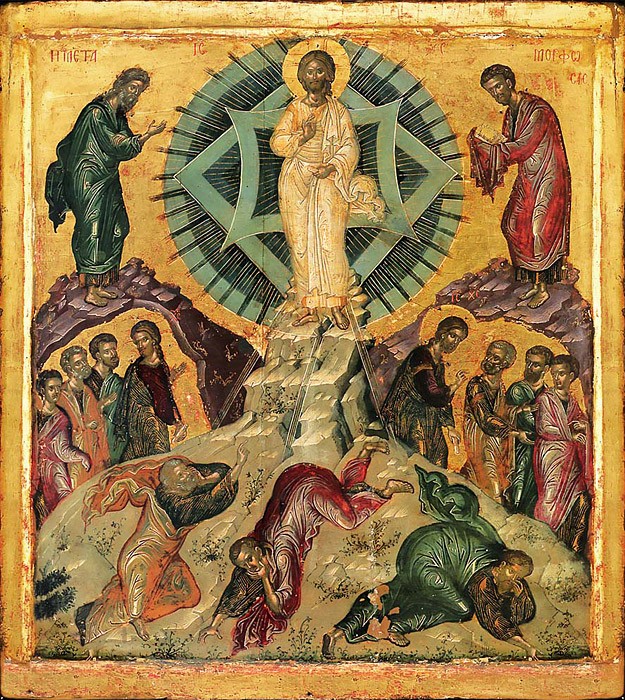

- The Transfiguration. The oldest versions of this icon date from the sixth century and already differ considerably between themselves. At the Church of St. Apollinaris in Classe in Ravenna, the artist did not dare show Christ transfigured and in His place we see a cross marked with the letters alpha and omega, in sphere of glittering stars. The prophets Moses and Elijah with him are presented in the form of half-figures dressed in white appearing out of the clouds, while out of the clouds above the Cross emerges the hand of the Lord in a gesture of blessing. Mount Tabor is represented by an accumulation of small rocks scattered on a strip of earth, while the three white lambs gazing at the Cross symbolize the three apostles accompanying Christ. At St. Catherine's Monastery in Sinai we see, not the allusive symbol, but the human figure of Christ transfigured, in a radiant mandorla. Mount Tabor is absent. The three apostles on one side, and Moses and Elijah on the other, are aligned on the same multi-colored strip representing the earth. Until the eleventh century, the prophets are often included in the round or oval mandorla, after that no longer. Around the twelfth century the individual disciples begin to be personalized: St. John, the youngest and most impressionable, is lying on the ground covering his face with his hands, St. James has fallen to his knees and hardly dares turn his head, while St. Peter, kneeling, has his eyes fixed on Christ. From the fourteenth century onward are added the scenes of the climbing and descent of the mountain, and of Christ helping his disciples back onto their feet.

Similar and even more developed historical research is are possible on any topic, whether the Feasts or scenes from the Gospels, images of saints, the Lord Himself or the Mother of God. The iconography of Mary, in particular, can serve already on its own as evidence that the canon was not seen as a fixed and ever rigid dogma. There are over two hundred variants of her image, over two hundred patterns that appear gradually in the representations of the Mother of God. Easily recognizable, they are piously preserved in the Church's heritage, being included in the liturgical calendar. As many again are venerated on a local basis. Only a small portion of these icons appeared miraculously, that is to say, they were found in a forest, on a mountain, or floating on the waves of the sea, as mysterious objects, belonging to no one and coming from no one knew where. But most of the images, as attested and confirmed by the iconographic sources of icons of the Mother of God, were generated by the creative audacity of many artists, following the wishes of those commissioning them.

If the Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II, over a thousand years ago, established for iconographers that the Incarnation of God in human form allows us to represent Him, can we, or should we, deduce from this that the icon depicts only things that really been seen by someone? Were they fixed once and for all in an absolutely concrete and objective manner, with a view to subsequent humble copying? How did this fixing take place? Where is this "photographic film"? Moreover, in canonical iconography, there are plenty of examples of pictures of people and things that have never been seen by anyone. Who saw the wings of angels of the Trinity visiting Abraham? Why before the fifth century had nobody seen winged angels, and why, in the centuries thereafter, did no one see wingless angels? Why is St. John the Forerunner seen without wings when part of the Deisis but with wings in other iconographic types? Who has ever seen the spirits of the Sea and the Jordan that appear in the icon of the Theophany? Who has seen the unpleasant old man, representing the spirit of doubt in the icon of the Nativity of Christ? Or the old man with his twelve rolls, representing the cosmos in the icon of Pentecost? Why, in this same composition, is the Mother of God still present among the Apostles until the 9th-10th centuries, with the dove of the Holy Spirit above her head, and why from the twelfth century onwards is she no longer painted among the apostles, even though the passage in the Acts of the Apostles mentioning here presence in the house remained unchanged? Who saw the soul of the Mother of God in the form of a tightly-wrapped baby in the arms of her Son in the icon of the Dormition? Or the angel with his sword severing the hands of the Jewish profaner? Who saw the clouds bearing the apostles to the bedside of the dying Mother of God in the icon of the Dormition (some icons show one apostle per cloud, others three, in some icons the clouds are pulled by angels, and in others they are self-propelled)? We could continue this list ad libitum, but we will stop here, especially as we have no sympathy for the categorical and rather vulgar tone employed generally by those trying to establish everything, to fix everything and to explain everything in sacred art, so as to give or refuse to each iconographer a "certificate of holiness."

Instead of vainly seeking the origin of the canonical patterns using false mystical explanations that are external to artistic creation, we should have more confidence in the Orthodox practice of painting and the veneration of icons. The canon is still expanding and widening today just as it did centuries ago, the only difference being that the current level of the general and theological training of painters is much higher than before. Today icons are painted of recently canonized saints, either from photos or simple descriptions.

New icons are being created for ancient saints for whom images did not previously exist or else did not come down to us, owing to the absence of or severing of the sacred art tradition in their home countries. Such icons are "invented" by artists, by analogy with existing icons of saints who have experienced a similar spiritual path, or had a similar lifestyle, with the addition of local features.

What we see initially in such cases is number of attempts to create new subjects, with greater or less success. After a while, one of these versions comes to dominate, that is to say it becomes better known, more famous, and is therefore more often copied and disseminated by means of reproductions. Many times this is the most interesting version from an artistic viewpoint, one that gives a compelling, individualized psychological portrait of the saint, the image of a living man, following in the footsteps of Christ and resembling him. Icons are also painted based on old frescoes and miniatures, as hundreds of rare and interesting compositions have remained hidden for centuries in libraries in remote monasteries, and are now being made accessible to the world through reproductions that all Christians can consult. The iconographic canon of representations of the Mother of God is expanding, this is new versions are painted that are then examined and declared canonical. These representations did not previously exist: they carry a particular, contemporary nuance of the Orthodox vision of the Mother of God. Icons are painted in memory of certain contemporary events, for example the icon of the Holy Innocents of Bethlehem in memory of the Beslan terrorist attack, the icon of the Mother of God of Akhtyrka in relation to miracles of miraculous protection occurring during the war in Chechnya, and many others.

What can we deduce from all this? That the iconographic canon is so vague that its very existence is questionable, and not worth our attention? Not at all! Faithfulness to the canon is an essential feature of the icon, but we need to understand clearly which this 'faithfulness' involves. Being faithful to the canon is not a matter of being forced to copy eternally and slavishly the same models established once and for all, but of following the tradition freely and with love, and to continue it in the same spirit. If the Church, in its wisdom, has always refrained and still refrains from strict and concrete prescription, then it behooves us, as spectators and judges, to be all the more careful and sensitive. Alas, often a judgement of non-canonicity expresses no more than the ignorance and obscurantism of the person judging it. The artist wanting to be faithful to canonical iconography must, above all, be familiar with historical iconography in all its richness, particularly that of the first millennium and of the united Church, forming the root and basis of all further development of Christian art.

In taking the decision to create a new version of any subject (from a commission or his own initiative) the artist must look for analogies in the treasures of the past, and in the process verifying his own theology. When adding into new icons features that are without theological significance but serve only to "update" the icon, both the artist and the commissioning party should be careful not to cross a certain red line, remembering that the icon serves first what is eternal, and should take particular care not to turn the icon into a tract on any current issue.

Of course, the decision on the canonicity of an icon (who should be portrayed, what should be painted, where and in what position?) does not belong to the artist but to the Church, beginning with members of the hierarchy, who bear primary responsibility. By contrast, the question of how to paint is entirely in the hands of the artist. The next chapter will address this question of how, that is to say the style.

The simple translation of the Greek does not help: "canonical" describes something that is regular, according to the rule. And indeed, how do we establish which icons are regular or "true" according all their different characteristics? In current practice, the term "canonical icon" has a very specific meaning: it is an icon that conforms with the iconographic canon, a concept not to be confused with the style, as poorly instructed people often do.

Canon and style - these concepts are so different that one and the same icon can be flawless in its iconography (i.e. canonicity) and totally unacceptable in terms of style. Conversely, the iconography may be archaic, and style excellent (as happens when artists from the capital are invited to the provinces, where person commissioning their work are unfamiliar with the latest themes and compositional findings). Conversely, the style may be archaic, and iconography highly developed (this happens when a theologian from the capital orders a work from a local self-taught artisan). The iconography can be "western" and the style "eastern" (the most striking example being the Sicilian Catholic churches of the twelfth century).

Or the other way round, the iconography can be "oriental" and the style "western" (examples abound, especially Athonite and Russian icons of the Theotokos from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, which often retain the traditional "Byzantine" typology).

And finally, a style that is impeccable in its style may prove uncanonical: for example, the icons of Old Testament trinity with the cross halo on one of the angels. Here the uncanonical iconography is easily fixed by removing the cross on the nimbus. However, the stylistic mismatch of the icon with the truth of the Church not infrequently results in a situation that can be fixed only by repainting the icon in another, acceptable style, i.e. by destroying the original image. We shall discuss below what is acceptable and unacceptable style, but in the present chapter the subject of our attention will be the iconographic canon.

Первая половина 15 в., ГРМ

The iconographic canon is the outline, or pattern, or "scheme" of a subject that is theologically well-founded. In other words, which persons and objects need to be included in the presentation, how do they inter-relate, and what clothing and postures should they have. This canon can be represented by a simplified technical drawing, or even by a text alone.

Should we then assume that there are collections of such patterns; approved and promoted by a supreme body of ecclesiastical power (like, for example, a council) as was the case when defining the texts of the New Testament canon? Such collections exist, known in Russian as podlinnik, derived from the old Russian word "podlinnii" meaning "true". The oldest of these collections date from the eleventh century in Greece and the sixteenth century in Russia. The drawings (prorissi) and descriptive text of which they are composed have been gathered from existing icons. These podlinnik known in some twenty different redactions, that of Sophia, of Siiski, Stroganov, Pomorie, the Leaves of Kiev, and a host of others, with the quality and precision of the descriptions improving over time. Not one of these redactions is complete.

Their instructions vary from one redaction to another, with comments at times including criticisms such as: "That is quite incorrect, because he (the writer is talking about St. Theodore of Pamphylia, presented as an old man, dressed as a bishop) was still young when he suffered martyrdom for Christ, and was never a bishop.”[1] "Or even blunter: "Stupid iconographers have taken to representing quite incorrectly the holy martyr Christopher with a dog's head ... which is nonsense."

[1] Quoted by Theodore Bouslaieff, Подлинник по редакции XVIII века in Богословие образа. Икона и иконописцы. Антология under edited by of A .N. Strijov, Moscow, 2002, p. 242.

But we should not dwell excessively on the contradictions and nonsense in the podlinnik: much more important is the fact that they are first and foremost practical manuals for artists, and as such do not have the normative and binding force of ecclesiastical documents. The Church has never desired to freeze its artists' creativity of artists through constraining decisions. The Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II (787), meeting in response to iconoclasm and prescribing the creation of sacred images, neither established or commissioned any normative collection which would have limited the permitted representations, not more than did the Russian Councils of the Hundred Chapters (1555) and Moscow (1666-1667). On the contrary, from the start, while inviting artists to follow recognized models, the council had already anticipated the possibility of the enlargement and change of the canon. It is precisely in expectation of this enlargement, not so as to restrict it, that the Council of Nicaea II called for a stronger sense of responsibility, entrusting this responsibility to the senior hierarchy of the Church.

In 787, it was of course technically impossible to create and disseminate a normative collection of iconographic patterns, but it is noteworthy that such an exercise has never been undertaken by the Church. The only existing collections are, as we have said, simple practical manuals for artists, in no ways emanating from the Church hierarchy. Neither the Council of the Hundred Chapters in 1551 nor the Grand Council of Moscow of 1666-7, both vital councils in the history of Russian iconography, established any normative document, either by consecrating an existing podlinnik or by reference to some of the best-known icons. Engravings and printed books were already very widespread in Russia, and every iconographic workshop had its own larger or smaller stock of model drawings. But no one found it necessary to sort, systematize and edit them.

It is true that even serious books cite a truncated extract from the Deeds of the Council of the Hundred Chapters supposedly prescribing that "artists should paint icons according to ancient models, such the Greek artists use to and still paint them. Let them paint as Rublev painted". These two sentences are presented incorrectly as a prescription requiring artists to ever copy the works of the early painters, and particularly those of Andrei Rublev. It is important to point here to an unfortunate mistake, and a certain persistence in ignorance, due to the way this quotation has been truncated and taken out of its context. Let us complete it: "as Rublev and other famous iconographers painted, let them sign the works "Holy Trinity", and let them not change anything with their own imagination (that of the artists)."

Let us not be held up by the various interpretations of terms such as "painted and paint" or "other famous iconographers." Let us simply point out that this quote is not an authoritative decision to mark out the path for the entire future development of Russian iconography, but that it constitutes simply the response (and not just part of it) to the question Ivan IV had put to the Council: "Should we, in the icons of the Holy Trinity, place the cruciferous nimbuses on all three angels? Or should we place a nimbus only on the central angel, and marking it with the name of Christ?”[1]

By falsifying the texts in this way, either intentionally or in ignorance, these authors have maintained the unfounded myth of a certain canon established in writing by the Church at a particular point in time. Notably, though, these authors fail to define this canon, even if, according to their writings, deviating only one step to the left or right is enough to hurl one into the abyss of heresy. The stage is set for iconographic witchhunts!

Before emitting any judgements on canonicity, it is especially important to realize that in fact neither the time of the Undivided Church or in Eastern Orthodoxy have there existed, and until today there still do not exist, any rules or any document that regulate and stabilize the iconographic canon. Simply, the iconography of the Church has developed continuously over two millennia, in a regime of informal self-regulation, with the best advances retained, and the less successful ones left to wither on the vine, but without vociferous condemnations. There has been a constant search for novelty, not for novelty’s sake, but above all for the greater glory of God, and often in the process resurrecting additions to the canon disregarded in earlier times.

Here are some examples of changes in the iconographic canon over the centuries. This presentation is by no means exhaustive, it is intended only to open the eyes of Westerners convinced of the frozen and binding nature of the iconographic canons.

- The Annunciation. This iconographic subject has been around since the 3rd century, and already from this time with three variants (Mary at the well, Mary spinning, and Mary reading). Archangel Gabriel gained wings only between the fifth and sixth centuries.

[1] Deeds of the Council of Hundred Chapters, chap. 41, issue 1.

Фреска катакомб Присциллы, Рим, 3 в.

In the eighth century there appeared at Nicaea the variant "Annunciation with the child in the womb," which would remain unique in its kind for a long time, until resurrected in Russia in the twelfth century, but becoming popular only in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, only then to disappear almost completely.

"Устюжское Благовещение" 12 в.

- The Epiphany (Baptism of Christ). The earliest images of the Baptism of Christ (fourth - fifth centuries) show a beardless Christ, naked, fully frontal, with the waters of Jordan's covering him up to the shoulder. Often included in the composition is the figure of the prophet Isaiah, who had prophesied the Epiphany. The angels holding cloths appear only in the eleventh century. The perizonium (loincloth) of Christ, who is immersed only to the ankles, appears in the twelfth century, and at this point too St. John the Baptist starts to be clothed with a hair shirt, rather than a tunic and chiton. It is from this time also, that we find images of Christ in three-quarters profile, turned to John, and covering his genitals with his hand.

Равенна, Арианский баптистерий, 5 в.

Мюстайр (Швейцария), 800 г.

-Christ. In the early centuries, we identify three different types in the iconography of the Savior: the Syrian type (black hair with an oriental type face), Roman (with a beard divided in two and blond hair), and finally a beardless youth (especially in the miracle scenes).

Нерези

Арль, Археологический музей, 4 в.

Лондон, Музей Виктории и Альберта, 8 в.

- The Transfiguration. The oldest versions of this icon date from the sixth century and already differ considerably between themselves. At the Church of St. Apollinaris in Classe in Ravenna, the artist did not dare show Christ transfigured and in His place we see a cross marked with the letters alpha and omega, in sphere of glittering stars. The prophets Moses and Elijah with him are presented in the form of half-figures dressed in white appearing out of the clouds, while out of the clouds above the Cross emerges the hand of the Lord in a gesture of blessing. Mount Tabor is represented by an accumulation of small rocks scattered on a strip of earth, while the three white lambs gazing at the Cross symbolize the three apostles accompanying Christ. At St. Catherine's Monastery in Sinai we see, not the allusive symbol, but the human figure of Christ transfigured, in a radiant mandorla. Mount Tabor is absent. The three apostles on one side, and Moses and Elijah on the other, are aligned on the same multi-colored strip representing the earth. Until the eleventh century, the prophets are often included in the round or oval mandorla, after that no longer. Around the twelfth century the individual disciples begin to be personalized: St. John, the youngest and most impressionable, is lying on the ground covering his face with his hands, St. James has fallen to his knees and hardly dares turn his head, while St. Peter, kneeling, has his eyes fixed on Christ. From the fourteenth century onward are added the scenes of the climbing and descent of the mountain, and of Christ helping his disciples back onto their feet.

Similar and even more developed historical research is are possible on any topic, whether the Feasts or scenes from the Gospels, images of saints, the Lord Himself or the Mother of God. The iconography of Mary, in particular, can serve already on its own as evidence that the canon was not seen as a fixed and ever rigid dogma. There are over two hundred variants of her image, over two hundred patterns that appear gradually in the representations of the Mother of God. Easily recognizable, they are piously preserved in the Church's heritage, being included in the liturgical calendar. As many again are venerated on a local basis. Only a small portion of these icons appeared miraculously, that is to say, they were found in a forest, on a mountain, or floating on the waves of the sea, as mysterious objects, belonging to no one and coming from no one knew where. But most of the images, as attested and confirmed by the iconographic sources of icons of the Mother of God, were generated by the creative audacity of many artists, following the wishes of those commissioning them.

If the Seventh Ecumenical Council of Nicaea II, over a thousand years ago, established for iconographers that the Incarnation of God in human form allows us to represent Him, can we, or should we, deduce from this that the icon depicts only things that really been seen by someone? Were they fixed once and for all in an absolutely concrete and objective manner, with a view to subsequent humble copying? How did this fixing take place? Where is this "photographic film"? Moreover, in canonical iconography, there are plenty of examples of pictures of people and things that have never been seen by anyone. Who saw the wings of angels of the Trinity visiting Abraham? Why before the fifth century had nobody seen winged angels, and why, in the centuries thereafter, did no one see wingless angels? Why is St. John the Forerunner seen without wings when part of the Deisis but with wings in other iconographic types? Who has ever seen the spirits of the Sea and the Jordan that appear in the icon of the Theophany? Who has seen the unpleasant old man, representing the spirit of doubt in the icon of the Nativity of Christ? Or the old man with his twelve rolls, representing the cosmos in the icon of Pentecost? Why, in this same composition, is the Mother of God still present among the Apostles until the 9th-10th centuries, with the dove of the Holy Spirit above her head, and why from the twelfth century onwards is she no longer painted among the apostles, even though the passage in the Acts of the Apostles mentioning here presence in the house remained unchanged? Who saw the soul of the Mother of God in the form of a tightly-wrapped baby in the arms of her Son in the icon of the Dormition? Or the angel with his sword severing the hands of the Jewish profaner? Who saw the clouds bearing the apostles to the bedside of the dying Mother of God in the icon of the Dormition (some icons show one apostle per cloud, others three, in some icons the clouds are pulled by angels, and in others they are self-propelled)? We could continue this list ad libitum, but we will stop here, especially as we have no sympathy for the categorical and rather vulgar tone employed generally by those trying to establish everything, to fix everything and to explain everything in sacred art, so as to give or refuse to each iconographer a "certificate of holiness."

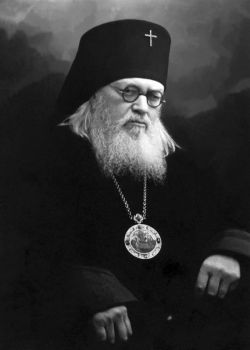

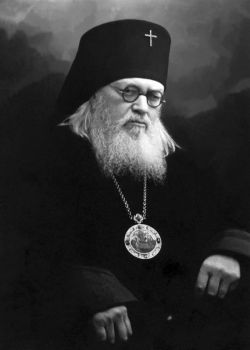

Instead of vainly seeking the origin of the canonical patterns using false mystical explanations that are external to artistic creation, we should have more confidence in the Orthodox practice of painting and the veneration of icons. The canon is still expanding and widening today just as it did centuries ago, the only difference being that the current level of the general and theological training of painters is much higher than before. Today icons are painted of recently canonized saints, either from photos or simple descriptions.

New icons are being created for ancient saints for whom images did not previously exist or else did not come down to us, owing to the absence of or severing of the sacred art tradition in their home countries. Such icons are "invented" by artists, by analogy with existing icons of saints who have experienced a similar spiritual path, or had a similar lifestyle, with the addition of local features.

What we see initially in such cases is number of attempts to create new subjects, with greater or less success. After a while, one of these versions comes to dominate, that is to say it becomes better known, more famous, and is therefore more often copied and disseminated by means of reproductions. Many times this is the most interesting version from an artistic viewpoint, one that gives a compelling, individualized psychological portrait of the saint, the image of a living man, following in the footsteps of Christ and resembling him. Icons are also painted based on old frescoes and miniatures, as hundreds of rare and interesting compositions have remained hidden for centuries in libraries in remote monasteries, and are now being made accessible to the world through reproductions that all Christians can consult. The iconographic canon of representations of the Mother of God is expanding, this is new versions are painted that are then examined and declared canonical. These representations did not previously exist: they carry a particular, contemporary nuance of the Orthodox vision of the Mother of God. Icons are painted in memory of certain contemporary events, for example the icon of the Holy Innocents of Bethlehem in memory of the Beslan terrorist attack, the icon of the Mother of God of Akhtyrka in relation to miracles of miraculous protection occurring during the war in Chechnya, and many others.

What can we deduce from all this? That the iconographic canon is so vague that its very existence is questionable, and not worth our attention? Not at all! Faithfulness to the canon is an essential feature of the icon, but we need to understand clearly which this 'faithfulness' involves. Being faithful to the canon is not a matter of being forced to copy eternally and slavishly the same models established once and for all, but of following the tradition freely and with love, and to continue it in the same spirit. If the Church, in its wisdom, has always refrained and still refrains from strict and concrete prescription, then it behooves us, as spectators and judges, to be all the more careful and sensitive. Alas, often a judgement of non-canonicity expresses no more than the ignorance and obscurantism of the person judging it. The artist wanting to be faithful to canonical iconography must, above all, be familiar with historical iconography in all its richness, particularly that of the first millennium and of the united Church, forming the root and basis of all further development of Christian art.

In taking the decision to create a new version of any subject (from a commission or his own initiative) the artist must look for analogies in the treasures of the past, and in the process verifying his own theology. When adding into new icons features that are without theological significance but serve only to "update" the icon, both the artist and the commissioning party should be careful not to cross a certain red line, remembering that the icon serves first what is eternal, and should take particular care not to turn the icon into a tract on any current issue.

Of course, the decision on the canonicity of an icon (who should be portrayed, what should be painted, where and in what position?) does not belong to the artist but to the Church, beginning with members of the hierarchy, who bear primary responsibility. By contrast, the question of how to paint is entirely in the hands of the artist. The next chapter will address this question of how, that is to say the style.