onanistic apologetics III

― for T.H. Chance

There is but one truly serious moral problem, and it is that of apology. To make an apology, man must both acknowledge an external standard and defer to it. This much is easily attained. The hard part comes in requiring that his deference be both sincere and spontaneous.

Many a formally correct example does not and cannot count as a proper apology. Charles Crighton’s movie A Fish Called Wanda features Kevin Kline as Otto West, a knuckle-headed jewel thief who resents being called stupid. When Archie Leach (John Cleese), the barrister playing an important part in Otto’s scheme, impugns Otto’s intelligence, he promptly finds himself responding to Otto’s demand for an apology, whilst being dangled by his feet out a fifth story window.

Archie: All right, all right, I apologize.

Otto: You’re really sorry.

Archie: I’m really really sorry, I apologize unreservedly.

Otto: You take it back.

Archie: I do, I offer a complete and utter retraction. The imputation was totally without basis in fact, and was in no way fair comment, and was motivated purely by malice, and I deeply regret any distress that my comments may have caused you, or your family, and I hereby undertake not to repeat any such slander at any time in the future.

Otto: OK.

Archie is a lawyer. He has a way with words. But in spite of his skills and training, he cannot deliver a meaningful apology to Otto. Archie’s apology is vacuous and futile. It is vacuous because it has been coerced under duress. It is futile because it is undeserved by its recipient. An effective apology freely acknowledges and redeems a valid debt to the aggrieved party. Whether or not it is accompanied by material restitution, it must comprise a moral reparation, by way of several complementary factors. The apology must acknowledge the offense. Archie has done as much in his litany. But mere acknowledgement cannot suffice. The offense may have been well warranted by the nature of the offended party. Otto is stupid. Witness Otto’s partner in cupidity, Wanda Gershwitz (Jamie Lee Curtis): “I’ve known sheep that could outwit you! I’ve worn dresses with higher IQs!” If he were called upon to testify to Otto’s intelligence, Archie would be remiss in identifying him otherwise. Only the tissue of social convention stands in the way of his volunteering this identification unsolicited. A different social convention debars Otto from retaliating against Archie’s disparagement of his intelligence. The penalties for transgressing these conventions are unequal. Outspokenness uncalled for is censured as an offense against manners, whereas violence unprovoked by its like is punished as an offense against the law.

In their fictional ecosystem of comic outlaws, the apologist and his antagonist soon change places in rendering ineffectual amends, only to confront each other in vying for Wanda and her loot. All arrive at condign deserts. Archie and Wanda get married in Rio, have seventeen children, and found a leper colony. Otto emigrates to South Africa and becomes Minister for Justice. The farce wraps up in a gratifying fashion, leaving largely unpunished a vast assortment of felonies and misdemeanors, and mooting the demands of morals and manners. Somewhere off screen, an insurance adjuster works overtime to balance the scales of equity. But his drudgery fails to generate the buzz of romance, rampage, and larceny. For an effective example in the apologetic genre, we must turn elsewhere.

It is instructive to set the issue in the classical perspective. The word apology comes into English from the Greek ἀπολογία. On its way, it has acquired the implication of excuses and amends absent in the Greek original, meaning simply and precisely a defense. This meaning endures in some English cognates. An apologist is one who argues in defense of an individual or a doctrine. He does so in the practice of apologetics, a discipline of argued defense. His aims in regard of excuses are the opposite of the aims of a supplicant. Both of them define themselves in relation to impartial justifications. Making an apology in either sense depends on submitting oneself to a standard of authority. Apologetics seeks to connect with convictions. Supplication seeks to redeem grievances. Their path to connecting or redeeming proceeds through justifications. As an argued defense, the apology sets its goal of eliciting conviction in its audience. The highest standard of such conviction is warranted by knowledge. As a deferential supplication, the apology sets its goal of freely acknowledging and redeeming a valid debt owed by the petitioner to the petitionee. This goal is defined in relation to the sensibilities, convictions, and interests of the latter, as mediated by the reasons of the former. The starting point of every effective apology is submission to the judgment of the aggrieved party. The final determination of its outcome is up to him. A valid apology is never a foregone conclusion.

Socrates made his unrepentant apology in submission to the Athenian law. He warranted his submission by suffering its death sentence willingly. Augustine made his contrite Confessions in submission to the Christian doctrine. He warranted his submission by renouncing the pleasures of the flesh. A step away from their sublimity, Gregg Easterbrook made his disclaimer of anti-Semitism in submission to the Elders of Zion. He warranted his apology by retaining his job as a wag in the kosher employ of Marty Peretz. What is a man to do, who has no higher standard to dominate him?

The question persists even in the absence of defensive agenda. In making his confessions, Augustine accepts that men are as opaque to themselves as to others. The images that we form of ourselves fail to correspond to inner reality. Even in his Christian contrition, Augustine found himself as unpredictable in responding to temptation, as he was in his heathen youth:

tu enim, domine, diiudicas me, quia etsi nemo scit hominum quae sunt hominis, nisi spiritus hominis qui in ipso est, tamen est aliquid hominis quod nec ipse scit spiritus hominis qui in ipso est. tu autem, domine, scis eius omnia, quia fecisti eum. ego vero quamvis prae tuo conspectu me despiciam et aestimem me terram et cinerem, tamen aliquid de te scio quod de me nescio. et certe videmus nunc per speculum in aenigmate, nondum facie ad faciem. et ideo, quamdiu peregrinor abs te, mihi sum praesentior quam tibi et tamen te novi nullo modo posse violari; ego vero quibus temptationibus resistere valem quibusve non valeam, nescio. et spes est, quia fidelis es, qui nos non sinis temptari supra quam possumus ferre, sed facis cum temptatione etiam exitum, ut possimus sustinere. confitear ergo quid de me sciam, confitear et quid de me nesciam, quoniam et quod de me scio, te mihi lucente scio, et quod de me nescio,tamdiu nescio, donec fiant tenebrae meae sicut meridies in vultu tuo.

― Confessions, X.5.7

For Thou, Lord, dost judge me: because, although no man knoweth the things of a man, but the spirit of a man which is in him, yet is there something of man, which neither the spirit of man that is in him, itself knoweth. But Thou, Lord, knowest all of him, Who hast made him. Yet I, though in Thy sight I despise myself, and account myself dust and ashes; yet know I something of Thee, which I know not of myself. And truly, now we see through a glass darkly, not face to face as yet. So long therefore as I be absent from Thee, I am more present with myself than with Thee; and yet know I Thee that Thou art in no ways passible; but I, what temptations I can resist, what I cannot, I know not. And there is hope, because Thou art faithful, Who wilt not suffer us to be tempted above that we are able; but wilt with the temptation also make a way to escape, that we may be able to bear it. I will confess then what I know of myself, I will confess also what I know not of myself. And that because what I do know of myself, I know by Thy shining upon me; and what I know not of myself, so long know I not it, until my darkness be made as the noon-day in Thy countenance.

― translated by E.B. Pusey

The reader comes to know the character identified as Augustine. This character exists at the disposal of an author known by the same name. The contingency of their adequacy and authority in representing the autobiographical narrative is a matter of constant show and tell for the character and the author alike. Their reader learns time and again that their faithful account of the past depends entirely on the authority of God intervening to guarantee its truth. Augustine the author knows Augustine the protagonist of Augustine the literary character only through knowing God. Likewise, and all the more so, emerge the sources of his knowledge of other people. Man’s knowledge of other men and of their minds, comes to him through the same dispensation as self-knowledge, in consequence of knowing God. But Augustine has no place other than his own mind, wherein to search for and find his God.

If there be no such place, if there be no such recourse anywhere at all, what remains of apologetic justification? To justify himself as a man, man must fit his life within the bounds set by his kind. To justify himself as himself, man must set his life outside of the herd. He must make himself at one equal and unequal. And he must do so by pleading his own case justly, before himself. His endeavor is hobbled by the fundamental tenet of practical deliberation:For instance, it is thought that justice is equality, and so it is, though not for everybody but only for those who are equals (ἴσος); and it is thought that inequality is just, for so indeed it is, though not for everybody, but for those who are unequal (ἄνισος); but these partisans strip away the qualification of the persons concerned, and judge badly. And the cause of this is that they are themselves concerned in the decision, and perhaps most men are bad judges when their own interests are in question (σχεδὸν δ’ οἱ πλεῖστοι φαῦλοι κριταὶ περὶ τῶν οἰκείων).

― Aristotle, Politics, Book III, Chapter 9, 1280a14-16, translated by H. Rackham

Aristotle’s reasoning resonates through Western political traditions. At the most authoritative social level, it is well established that law cannot make a man a judge in his own case. Justinian’s Digest 5.1.15.1 describes a judge who maliciously renders a decision in violation of law, as one who made the case his own. He is held to do this maliciously, where it is clearly proved that either favor, enmity, or even corruption, influenced him; and, under these circumstances, he can be forced to pay the true amount of the matter in controversy. The phrase pungently expresses the resulting incapacity of the judge. You cannot judge your own case. At common law, the question was broached in 1481, in Sir Thomas Littleton’s Tenures, a land law treatise. The definitive statement belongs to Sir Edward Coke in Dr. Bonham’s Case. The Royal College of Physicians convicted and imprisoned Thomas Bonham for practicing medicine without a license. When Bonham challenged his imprisonment, Coke, at the time the chief justice of the Court of Common Pleas, ruled that the Royal College lacked the authority to do so under its charter and a parliamentary statute. Because the Royal College was the entity that both suffered the wrong and collected the fine, it had acted as both a party and a judge in the dispute. Generalizing beyond this case, Coke famously declared that all such acts of Parliament “against common right and reason” were void, because no one ought to be a judge in his own cause, it is wrong for anyone to be the judge of his own property: “quia aliquis non debet esse Judex in propria causa, imo iniquum est aliquem sui rei esse judicem”.

Rousseau would have none of that. Following his ineffectual disclaimer of apologetics in the Confessions, he summarily appoints himself the judge of Jean-Jacques. And in the beginning of his career as a public intellectual, seeking his acclaim before the Dijon Academy, he flatters his judges for their capacity to rule in the matter of their own contribution to virtue:

Il sera difficile, je le sens, d’approprier ce que j’ai à dire au Tribunal où je comparois. Comment oser blâmer les Sciences devant une des plus savantes Compagnies de l’Europe, loüer l’ignorance dans une célebre Académie, et concilier le mépris pour l’étude avec le respect pour les vrais Savans ? J’ai vu ces contrariétés ; et elles ne m’ont point rebuté. Ce n’est point la science que je maltraite, me suis-je dit ; c’est la Vertu que je défends devant des hommes vertueux. La probité est encore plus chére aux Gens-de-bien que l’érudition aux Doctes. Qu’ai-je donc à redouter ? Les lumieres de l’Assemblée qui m’écoute ? Je l’avoüe; mais c’est pour la constitution du discours, et non pour le sentiment de l’Orateur. Les Souverains équitables n’ont jamais balancé à se condanner eux-mêmes dans des discussions douteuses ; et la position la plus avantageuse au bon droit est d’avoir à se défendre contre une Partie intègre et éclairée, juge en sa propre cause.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discours qui a remporte le prix a l’Académie de Dijon en l’année 1750. Sur cette Question proposée par la même Académie : Si le rétablissement des Sciences et des Arts a contribué à épurer les mœurs, OC III, p. 5

It will be difficult, I sense, to accommodate what I have to say to the Tribunal before which I am appearing. How can one dare to blame the Sciences before one of the most learned Societies in Europe, to praise ignorance in a famous Academy, and to reconcile contempt for study with respect for true Scholars? I have seen these contradictions, and they have not discouraged me. It is not science that I am mistreating, I told myself; it is Virtue that I am defending before virtuous men. Integrity is cherished among Good Men even more than erudition is among the Learned. So what am I to fear? The enlightened minds of the Assembly that is listening to me? I confess that is a fear; but it is for the construction of the discourse and not for the feelings of the Speaker. Equitable Sovereigns have never hesitated to condemn themselves in doubtful arguments; and the most advantageous position in a just cause is to have to defend oneself against an upright and enlightened Party, judge in his own case.

- translated by MZ

In contradistinction to this hopeful supplicant, whose success or failure depend entirely on the equanimity and good graces of his recipient, the clandestine apologist of Rousseau’s autobiography is his own plaintiff and defendant, investigator and expert, advocate and accuser, judge and jury. Above all, he is his own witness. In most matters, he is the sole witness to come forth. His difficulties arise in proportion to the authority and credibility required by these offices.

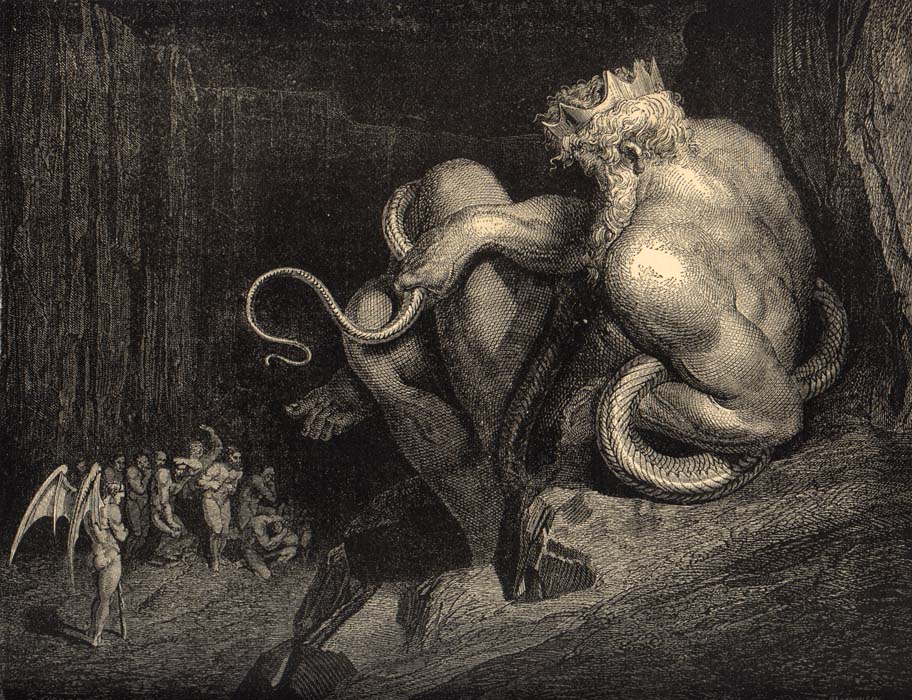

A view from the top of Mt. Olympus witnesses a complementary problem. Thus Socrates entreats the friends of Gorgias at 523a-527e, to give ear to a right fine story (καλός λόγος), which he expects them to regard as a fable (μῦθος), but intends as an actual account (λόγος … ἀληθής). In arguing against Callicles’ repudiation of conventional justice, Socrates draws on Homer’s account, of Zeus (Ζεύς), Poseidon (Ποσειδῶν), and Pluto (Πλοῦτος) dividing the sovereignty amongst them when they usurped it from their father Cronos (Κρόνος). He then extends the account of Hesiod in Works and Days, 170, of Isles of the Blest (αἱ τῶν Μακάρων νῆσοι), as the happy posthumous dwelling of hero-men of the fourth age of mankind, and that of Homer in the Iliad 8, 13, 481 of Tartarus (Τάρταρος) as the prison of the Titans. The novelty of his parable lies in declaring that all men who have lived unjustly and impiously shall go in the hereafter to the dungeon of requital and penance (τὸ τῆς τίσεώς τε καὶ δίκης δεσμωτήριον), even as all just and pious men shall find themselves in a happy place, as suggested by Homer in the Odyssey 4, 565. To this end Zeus put an end to the living men judging the living upon their dying day. He ruled that these cases were judged ill because those who were on trial were tried in their clothing, for they were tried alive. For many who have wicked souls are clad in fair bodies and ancestry and wealth, and at their judgement (κρίσις) appear many witnesses (μάρτυρες) to testify (μαρτυρέω) that their lives have been just (δίκαιος). Thus the living judges were confounded not only by their evidence, but at the same time by being clothed themselves while they sat in judgement, having their own soul muffled in the veil (προκαλύπτω) of eyes and ears and the whole body. All these habiliments were a hindrance to them (ἐπίπροσθεν γίγνεται), their own no less than those of the judged. Thus Zeus sent Prometheus (Προμηθεύς) to put a stop to men having foreknowledge of their death. Next he proclaimed that men standing trial must be stripped bare before they are tried. They must stand their trial dead. Their judge also must be naked and dead. In this way he is to behold with his very soul the very soul of each immediately upon his death. In this way, the defendant is to be left bereft of all his kin and all his fine array, so that the judgement may be just. And Zeus appointed sons of his own to be judges; two from Asia, Minos (Μίνως) and Rhadamanthus (Ῥαδάμανθυς), and one from Europe, Aeacus (Αἴακος). Since their death these three sit in judgement in the meadow at the dividing of the road, whence are the two ways leading, one to the Isles of the Blest, and the other to Tartarus. And Rhadamanthus tries those who come from Asia, and Aeacus tries those from Europe, and Minos renders the final decision, if the other two be in any doubt.

And so they are free to contemplate each soul (ψυχή) as it might be scourged (διαμαστιγόω) with the work of perjuries and injustice (ἐπιορκιῶν καὶ ἀδικίας) or awry (σκολιά) through falsehood and imposture (ὑπό ψεύδους καὶ ἀλαζονείας) or full fraught with disproportion and ugliness (ἀσυμμετρίας τε καὶ αἰσχρότητος) as the result of an unbridled course of fastidiousness, insolence, and incontinence (καὶ τρυφῆς καὶ ὕβρεως καὶ ἀκρατίας). These souls they consign to punishment in the netherworld. But when the judge discerns another soul that has lived a holy (ὅσιος) life in company with truth (μετ' ἀληθείας), especially one belonging to a philosopher (φιλόσοφος) who has minded his own business and not been a busybody (πολυπραγμονέω) in his lifetime, he is struck with admiration and sends it off to the final reward.

The philosophical counsel of Socrates aims at connecting true happiness (εὐδαιμονία) to a proper, geometrical order of actions and passions. His solution comes through relentless restraint of raw appetite. His lineage lies in the tradition sustained by that other great beneficiary of an inner voice, Samuel Beckett, whereby “the wisdom of all the sages, from Brahma to Leopardi, the wisdom that consists not in the satisfaction, but the ablation of desire.” (Proust, Grove Press: New York, 1957, p. 7) Man cannot attain happiness, but through the practice of virtue. The tragic poets follow the father of history in supporting this conclusion with object lessons of precipitous downfall.

In his version of Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck, Tom Waits instructs his audience to call no man happy till he dies. Sophocles draws the same lesson in concluding Oedipus Tyrannus. Both of them rely on Herodotus, who tells in Histories 1.23-33 of Solon (Σόλων) visiting Croesus (Κροῖσος) in Sardis. After his servants showed Solon the magnitude and splendor of his royal treasures, in what appears to be the first recorded instance of appealing to the authority of philosophy (φιλοσοφέω), Croesus asked his Athenian guest, renowned for his wisdom (σοφία) and his wanderings, who, of all the men he had seen, was the happiest. (See the discussion of Herodotus’ priority in this designation by Pierre Hadot, in Qu’est-ce que la philosophie antique ?) Croesus believed himself to be the happiest of men. But Solon told the king of an Athenian named Tellus, who lived in a prosperous city, survived to see his children’s children, had sufficient wealth, met a soldier’s death after routing the enemy, fighting side by side with his countrymen, and received from them a state funeral on the spot where he fell in battle. Croesus pressed on, asking who was the second happiest person Solon had seen. Solon responded with the tale of two youths of Argos, Cleobis and Biton, who had enough to live on and were blessed with great physical strength. They won their glory at the Argive festival of Hera, by yoking themselves to their mother’s ox-cart and driving her to the temple of the goddess five miles away. After this feat, as the men congratulated the youths on their strength, while the women congratulated their mother for having borne such children, she prayed that Hera might grant the best thing for man to her children. After this prayer, the sacrificial rites and feasting were concluded, and the youths lay down in the temple and went to sleep and never rose again; death held them there. The Argives made and dedicated at Delphi statues of them as being the best of men. Vexed by Solon awarding the second prize for happiness (εὐδαιμονία) to these two youths, Croesus asked his Athenian guest, whether he so much despised his happiness that he did not even make him worth as much as common men. Solon answered that he could not answer the king’s question before he learned that he ended his life well:The very rich man is not more fortunate than the man who has only his daily needs, unless he chances to end his life with all well. Many very rich men are unfortunate, many of moderate means are lucky. The man who is very rich but unfortunate (ἄνολβος) surpasses the lucky man (εὐτυχής) in only two ways, while the lucky surpasses the rich but unfortunate in many. The rich (πλουτέω) man is more capable of fulfilling his appetites and of bearing a great disaster that falls upon him, and it is in these ways that he surpasses the other. The lucky man is not so able to support disaster (ἄτη) or appetite (ἐπιθυμία) as is the rich man, but his luck keeps these things away from him, and he is free from deformity (ἄπηρος) and disease (ἄνοσος), has no experience of evils (κακός), and has fine children and good looks. If besides all this he ends his life well, then he is the one whom you seek, the one worthy to be called fortunate. But refrain from calling him fortunate (ὄλβιος) before he dies; call him lucky. It is impossible for one who is only human to obtain all these things at the same time, just as no land is self-sufficient in what it produces. Each country has one thing but lacks another; whichever has the most is the best. Just so no human being is self-sufficient; each person has one thing but lacks another. Whoever passes through life with the most and then dies agreeably is the one who, in my opinion, O King, deserves to bear this name. It is necessary to see how the end of every affair turns out, for the god promises fortune to many people and then utterly ruins them.

― Herodotus, The Histories, 1.32.5-9, translated by A.D. Godley

Herodotus recounts the fulfillment of Solon’s admonition by a series of great misfortunes that befell Croesus. They culminated with Cyrus (Κῦρος) of Persia, threatening the kingdom of Lydia. Croesus consulted the oracle of Delphi in Greece. The oracle replied that if Croesus goes to war he will destroy a great empire. When Croesus met the army of Cyrus and was utterly defeated, he had destroyed his own great empire. Cyrus ordered Croesus to be burned alive. As the flames crept upward to consume him, Croesus cried out three times the name of Solon. Cyrus was so moved by the story of Solon’s warning to the proud king that he ordered Croesus to be released.

Socrates amplifies the lesson of the legendary Athenian lawgiver by transposing it from the domain of eudaimonic satisfaction to the realm of just deserts. Not only is man foreclosed from accounting in his lifetime for the goods that he has, or can expect to get; moreover, no one else can rule on his entitlement to punishment or reward, present and future. Similarly, in conjoining happiness with virtue, the heathen freethinker (παρρησιαστής) anticipates the devotional concerns of the Christian apologist. And in neglecting the vagaries of fortune, he exposes himself to rebuttal by the immoralist, perpetually tempted by the insufficiency of virtue for happiness. Even upon resigning himself to random misfortunes, the philosopher remains in thrall to his body and its organs of perception standing in the way of self-knowledge and judicial scrutiny required to account for the virtues and vices of their bearer. In his lifetime, such accounting perforce remains partial and provisional. It is vulnerable to all objections admissible in a court of law in regard to the witness testimony. It stands or falls on forensic grounds. And yet, Socrates did not shie away from bearing witness on his own behalf, with foreknowledge of his death, facing a jury of muffled souls, on these selfsame grounds of worldly justice. In keeping his apology free of supplication, he sealed his fate and set the tone for all subsequent attempts to render justifications or excuses. Thenceforth, it has been as much a matter of interpretation, as of argumentation.

In his life of Solon, Plutarch writes that the celebrated Athenian legislator grew old ever learning many things, “γηράσκειν αἰεὶ πολλὰ διδασκόμενος”. Rousseau opens his third solitary walk with this boast on the wisdom of age: Je deviens vieux en apprenant toujours. But he notes the irony in his own case: L’adversité sans doute est un grand maître ; mais ce maître fait payer cher ses leçons, et souvent le profit qu’on en retire ne vaut pas le prix qu’elles ont coûté. Adversity is undoubtedly a great teacher; but this teacher charges dearly for its lessons, and often the profit derived therefrom is not worth the price paid therefor. (OC I, p. 1011) Having relished social acclaim and the company of friends in his youth, the old man finds that they have fled him when his trouble began. He admits that it is too late to enjoy the lessons of this bitter experience. He resigns himself to giving up all vain strivings in anticipation of death, and learning how to die:

Ainsi retenu dans l’étroite sphere de mes anciennes connoissances, je n’ai pas, comme Solon, le bonheur de pouvoir m’instruire chaque jour en vieillissant, et je dois même me garantir du dangereux orgueil de vouloir apprendre ce que je suis désormais hors d’état de bien savoir. Mais s’il me reste peu d’acquisitions à espérer du côté des lumieres utiles, il m’en reste de bien importantes à faire du côté des vertus nécessaires à mon état. C’est-là qu’il seroit tems d’enrichir et d’orner mon ame d’un acquis qu’elle pût emporter avec elle, lorsque délivrée de ce corps qui l’offusque et l’aveugle, et voyant la vérité sans voile, elle appercevra la misere de toutes ces connoissances dont nos faux savans sont si vains. Elle gémira des momens perdus en cette vie à les vouloir acquérir. Mais la patience, la douceur, la résignation, l’intégrité, la justice impartiale sont un bien qu’on emporte avec soi, et dont on peut s’enrichir sans cesse, sans craindre que la mort même nous en fasse perdre le prix. C’est à cette unique et utile étude que je consacre le reste de ma vieillesse. Heureux si par mes progrès sur moi-même j’apprends à sortir de la vie, non meilleur, car cela n’est pas possible, mais plus vertueux que je n’y suis entré.

― Les rêveries du promeneur solitaire, troisiéme promenade, OC I, p. 1023

Thus confined to the narrow bounds of my former knowledge, I have not, like Solon, the happiness of being able to learn every day as I grow older; indeed I must refrain from the dangerous pride in wishing to learn what my condition no longer allows to know properly. But if there remain but few gains for me to hope for in the way of useful knowledge, there is still much I may attain in the way of virtues necessary to my situation in life. It is there that the time has come to enrich and adorn my soul with goods that she can carry along when, set free of this body that dazzles and blinds her, and seeing the truth unveiled, she comes to know the wretchedness of all that knowledge whereof our men of false learning are so vain. It will lament the moments wasted in this life on attempts to acquire it. But patience, kindness, resignation, integrity, impartial justice are goods that we can take with us, and wherein we can thrive continually without fear that death itself can deny to us their value. It is to this unparalleled and beneficial study that I devote what remains of my old age. And I shall be happy if by improving myself I learn to leave life, not better, for that is impossible, but more virtuous than when I entered it.

― translated by MZ

In pleading on his own behalf, Rousseau enjoys the advantage of double inheritance. He seeks to make his confession in the tradition of Augustine, even as he refuses contrition in the manner of Socrates. Contrary to the Greek mythos, he resolves to convey the truth of his condition without relinquishing his fleshly habiliments. Contrary to Christian humility, he presumes to know something of himself that the heavenly tribunal knows not. Even as he fails to pronounce the last word on Jean-Jacques, he succeeds in expressing the first word of Romantic exposure. In refusing all scientific certainty borne of abstractions, he arrogates the unimpeachable authority of subjective sentiment. The erratic nature of his readings in no way interferes with their standing at the summit of literary narcissism. His is the rarest kind of obsessive self-regard, proceeding from a supremely warranted need to realize an inner nature, in the way that runs counter to both to the protreptic (προτρεπτικός) ideal of Platonic ethics grounding virtue in knowledge, and the apotreptic (ἀποτρεπτικός) predicament of Socrates, perpetually turned away from temptation by his genius (δαιμόνιον). By contrast, the genius of Jean-Jacques breaks the ground for his monument in the way that renders him the pattern for all modernity, even as Socrates endures as the classical paradigm (παράδειγμα) of striving for wisdom and goodness. Whereas Socrates testifies (μαρτυρέω) in his life and death as a martyr to his vocation, Rousseau answers his calling by becoming a monster. But by tormenting himself and all who come near him, he compounds his capacity to fascinate from afar. As Socrates tells of his ignorance, as Augustine confesses his sins, they speak against themselves and against man. Alone in opposing them, Rousseau speaks for himself and for mankind. He is the only advocate that we deserve. Rousseau must be imagined happy.