Book Review: The Brothers Karamazov, by Fyodor Dostoevsky

One-line summary: Profound and profoundly long monologues about ethics, religion, and psychology pad this novel about three (or four) brothers, their villainous father, and the trial to determine which one killed him.

First published in 1880 (in Russian); approximately 358,000 words, or 600-800 pages depending on the edition. Available for free at Project Gutenberg.

The Brothers Karamozov is a murder mystery, a courtroom drama, and an exploration of erotic rivalry in a series of triangular love affairs involving the "wicked and sentimental" Fyodor Pavlovich Karamozov and his three sons - the impulsive and sensual Dmitri; the coldly rational Ivan; and the healthy, red-cheeked young novice Alyosha. Through the gripping events of their story, Dostoevsky portrays the whole of Russian life, its social and spiritual strivings, in what was both the golden age and a tragic turning point in Russian culture.

Okay, before delving into the substance of this book and why it's a Great Work and why I am not going to eagerly dive into another Dostoevsky novel any time soon, let's establish the plot and the characters (by the way, Russian characters are notoriously hard to keep straight if you're not familiar with Russian naming conventions, because each character may be referred to by half a dozen different names).

Basically, you have a vile, uncouth rich man, Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, who has three (possibly four) sons, all of whom he neglected and ignored. There is Dmitri the "sensualist," a dissolute playboy; Ivan the atheist, a tormented intellectual; Aleksey the monk, a kind and moral young man who's basically the protagonist of the novel; and Pavel Fyodorovich Smerdyakov, who is Fyodor's servant and rumored to be his illegitimate child.

Fyodor's murder, and the subsequent trial of his eldest son Dmitri ("Mitya"), is the main plot, but the murder doesn't actually happen until about halfway through, and the trial, at the climax, is not much of a mystery, because Dostoevsky has already told us who the murderer is and telegraphed what the outcome of the trial would be. So calling The Brothers Karamazov a "murder mystery" is not really accurate. The murder is the least interesting part of the book -- Dostoevsky spends the first half building up all the characters, establishing their relationships, and making the murder almost inevitable. But even then, it's only partly a character drama.

A digression on audiobooks which is not nearly as long as Dostoevsky's digressions on EVERYTHING

I listened to The Brothers Karamazov as an audiobook. Listening to audiobooks requires a certain ability to keep part of your attention focused on the narration even if you are also doing something else, like walking or driving. I know some people say they can't do it because their mind wanders. It's totally true that if you are prone to letting your mind wander, you can zone out and realize five minutes and an important scene or two has slipped by while you weren't listening that closely. Sometimes when I do this, I have to replay the parts I just missed. Other times, after reengaging my brain with what the narrator is saying, I "catch up" once I orient myself to who's speaking and what's going on (because weirdly, the words really do sort of sink into your brain even if you weren't paying attention and it's like you "remember" the last few minutes of dialog that you weren't really paying attention to).

My mind wandered a lot while listening to this book (all thirty-six hours of it). Most of the time, I'd "tune in" five minutes later, and the same character would be talking, as he had been talking for the last hour.

One of the criticisms of Ayn Rand (besides that she created a batshit insane philosophy arguing the moral imperativeness of sociopathy) is that her novels are padded with characters giving 50-page speeches. (Full disclosure: I've never made it through an Ayn Rand novel.) Rand was Russian-born, and while I don't know what her early literary influences actually were, it's not unreasonable to guess that she probably read Tolstoy and Dostoevsky growing up. So blame Dostoevsky! Yes, he does the same thing -- half of The Brothers Karamazov is characters giving long soliloquies about free will, moral authority, love, the evolution of Russian society, and whatever else Dostoevsky felt like rambling about. Okay, "rambling" is unfair -- a huge difference between Rand and Dostoevsky is that Rand spouted bullshit, while Dostoevsky spouted... well, brilliant philosophical ruminations or intellectual wankery, take your pick. At one point, an entire chapter is devoted to an allegorical tale by Ivan ("the atheist" -- more on this below) about Jesus returning to Earth, being imprisoned by the Spanish Inquisition, and being subjected to a long speech in which the Grand Inquisitor demands to know why he is interfering with his Church on Earth, when they are working to relieve man of the burden of free will he cruelly placed upon them. It's quite a cruel, witty, and articulate satire -- it also has nothing to do with the main story, only to do with clarifying Ivan's cynicism and non-atheism. Most of the time, characters go on and on like this for pages, with their audience saying not a word, or maybe occasionally interjecting a question. This is the author getting up on a soapbox, not advancing the plot. This may not be a flaw, if you don't regard "advancing the plot" as a necessary function of each chapter (and Dostoevsky definitely didn't).

Dostoevsky's Devil is more convincing than his atheist

Dostoevsky has an obvious blind spot: it's a very common blind spot among the devoutly religious. Dostoevsky regarded the existence of God to be so self-evident that he couldn't truly imagine an actual atheist. In his mind, atheists are people who know just like everyone else that God exists, but through contrariness, rebelliousness, dilettante philosophizing, or a wounded ego, they pretend to be scoffers. (Anyone who is an atheist has heard the "You know in your heart that God is real" argument plenty of times, usually followed by quoting Romans 14:11 if the believer is of a particularly sanctimonious variety.)

So Ivan, the "atheist," is really more of a skeptic. (Some descriptions of The Brothers Karamazov call him a "rationalist," but he often doesn't act all that rational). For all that he is supposedly an atheist, he spends most of his time thinking about (and being tormented by) God, religion, and the Devil. In fact, in one delirious episode, Ivan actually gets visited by the Devil, and has an argument about whether or not he's hallucinating him:

“Then even you don’t believe in God?” said Ivan, with a smile of hatred.

“What can I say?-that is, if you are in earnest-”

“Is there a God or not?” Ivan cried with the same savage intensity.

“Ah, then you are in earnest! My dear fellow, upon my word I don’t know.

There! I’ve said it now!”

“You don’t know, but you see God? No, you are not some one apart, you are

myself, you are I and nothing more! You are rubbish, you are my fancy!”

Even in his denial, it's clear that Ivan represents the straw-atheist that Dostoevsky believed all atheists to be: a man tormented by doubt who really wants to be convinced of God.

Now in fairness, Ivan is not stupid, malicious, or ignorant, and even when, earlier in the book, Father Zosima lumps atheists in with communists, anarchists, and other "evildoers," he speaks kindly of them and admits that some of them are good. Dostoevsky likewise seems to regard atheists benignly, but as wayward children.

Dostoevsky's devil is a perfectly devilish interlocutor, full of wit, humor, and malice so subtle it can slip right past if you're not paying attention. But it's yet another deviation from the story, interesting in terms of developing Ivan's character, and adding another stone to the observations Dostoevsky has piled up, but if you don't appreciate these little digressions for their own sake, you're not going to appreciate them at all.

The Trial

The thing is, you really should appreciate the digressions. (Or try.) Because Dostoevsky is a careful, thoughtful writer. His characters are larger than life archetypes, and hence like their grand speeches, their personalities are not really anything like what we'd likely encounter in reality. At the same time, viewed as illustrative caricatures, they are vivid, three-dimensional, and epic. Even the mean little bit-part players.

The trial is the culmination of everything there is to love and hate about this book. This isn't Law & Order: Dostoevsky describes the entire trial, and makes you listen to the entire arguments of the prosecutor and the defense. He was taking a few shots at the legal system here, and by making the prosecutor and the defense attorney both somewhat pompous, operatic fellows, and depicting the spiteful and romantic sentiments of the spectators, his commentary on the theatricality of the legal system is ironic in its contemporary relevance. But it's still a very careful, detailed (and, if your patience is running out, plodding) drama that hinges on the most minute details.

“I shall be told that he could not explain where he got the fifteen hundred that he had, and every one knew that he was without money before that night. Who knew it, pray? The prisoner has made a clear and unflinching statement of the source of that money, and if you will have it so, gentlemen of the jury, nothing can be more probable than that statement, and more consistent with the temper and spirit of the prisoner. The prosecutor is charmed with his own romance. A man of weak will, who had brought himself to take the three thousand so insultingly offered by his betrothed, could not, we are told, have set aside half and sewn it up, but would, even if he had done so, have unpicked it every two days and taken out a hundred, and so would have spent it all in a month. All this, you will remember, was put forward in a tone that brooked no contradiction. But what if the thing happened quite differently? What if you’ve been weaving a romance, and about quite a different kind of man? That’s just it, you have invented quite a different man!

What the Negative Reviewers Say

What do you think? If you've read all the teal deer above, then you can guess: Dostoevsky practically defines tl;dr. (According to the Wikipedia page, The Brothers Karamazov was intended it to be the first part of an epic story.)

You can't beat this one for succinctness:

I see your Dostoevsky and I raise you one Nabakov. What the heck is he talking about?

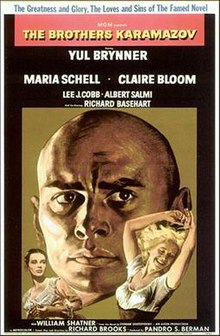

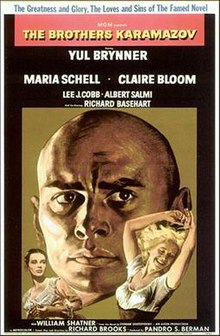

But you can always watch the movie

But not on Netflix. :(

There have been a number of Russian film versions made of The Brothers Karamazov, and there was a 1958 film starring Yul Brynner. Sadly, it's not available on Netflix, and while there are plenty of copies for sale on eBay, I just... was not feeling so inspired by the book that I was willing to pay money to see the movie. Maybe someday.

Verdict: Dostoevsky is someone you read for intellectual stimulation, not entertainment. (Well, not someone I would read for entertainment.) Is he a great writer? Yes. Is this book deep and meaningful? If you share Dostoevsky's religious views somewhat, then yes. But this is not the kind of book I can imagine loving and cherishing and wanting to reread for fun. I am glad to have read it, in the same way I'm glad to have passed a number of trials in my life that were good for me but not exactly experiences I'd want to repeat. Maybe Russian literature is just not for me; I'm happy to put The Brothers Karamazov back on its shelf and go read a nice space opera.

Although The Brothers Karamazov is one of the books on the 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die list, I did not read it for the books1001 challenge, so that honor is still awaiting someone else. ;) It's two months into the year and we've reviewed 48 of our 1001 books, so there are many, many books left to read. Please join us -- all you have to do is read and review one. (Though taking on more is encouraged!)

First published in 1880 (in Russian); approximately 358,000 words, or 600-800 pages depending on the edition. Available for free at Project Gutenberg.

The Brothers Karamozov is a murder mystery, a courtroom drama, and an exploration of erotic rivalry in a series of triangular love affairs involving the "wicked and sentimental" Fyodor Pavlovich Karamozov and his three sons - the impulsive and sensual Dmitri; the coldly rational Ivan; and the healthy, red-cheeked young novice Alyosha. Through the gripping events of their story, Dostoevsky portrays the whole of Russian life, its social and spiritual strivings, in what was both the golden age and a tragic turning point in Russian culture.

Okay, before delving into the substance of this book and why it's a Great Work and why I am not going to eagerly dive into another Dostoevsky novel any time soon, let's establish the plot and the characters (by the way, Russian characters are notoriously hard to keep straight if you're not familiar with Russian naming conventions, because each character may be referred to by half a dozen different names).

Basically, you have a vile, uncouth rich man, Fyodor Pavlovich Karamazov, who has three (possibly four) sons, all of whom he neglected and ignored. There is Dmitri the "sensualist," a dissolute playboy; Ivan the atheist, a tormented intellectual; Aleksey the monk, a kind and moral young man who's basically the protagonist of the novel; and Pavel Fyodorovich Smerdyakov, who is Fyodor's servant and rumored to be his illegitimate child.

Fyodor's murder, and the subsequent trial of his eldest son Dmitri ("Mitya"), is the main plot, but the murder doesn't actually happen until about halfway through, and the trial, at the climax, is not much of a mystery, because Dostoevsky has already told us who the murderer is and telegraphed what the outcome of the trial would be. So calling The Brothers Karamazov a "murder mystery" is not really accurate. The murder is the least interesting part of the book -- Dostoevsky spends the first half building up all the characters, establishing their relationships, and making the murder almost inevitable. But even then, it's only partly a character drama.

A digression on audiobooks which is not nearly as long as Dostoevsky's digressions on EVERYTHING

I listened to The Brothers Karamazov as an audiobook. Listening to audiobooks requires a certain ability to keep part of your attention focused on the narration even if you are also doing something else, like walking or driving. I know some people say they can't do it because their mind wanders. It's totally true that if you are prone to letting your mind wander, you can zone out and realize five minutes and an important scene or two has slipped by while you weren't listening that closely. Sometimes when I do this, I have to replay the parts I just missed. Other times, after reengaging my brain with what the narrator is saying, I "catch up" once I orient myself to who's speaking and what's going on (because weirdly, the words really do sort of sink into your brain even if you weren't paying attention and it's like you "remember" the last few minutes of dialog that you weren't really paying attention to).

My mind wandered a lot while listening to this book (all thirty-six hours of it). Most of the time, I'd "tune in" five minutes later, and the same character would be talking, as he had been talking for the last hour.

One of the criticisms of Ayn Rand (besides that she created a batshit insane philosophy arguing the moral imperativeness of sociopathy) is that her novels are padded with characters giving 50-page speeches. (Full disclosure: I've never made it through an Ayn Rand novel.) Rand was Russian-born, and while I don't know what her early literary influences actually were, it's not unreasonable to guess that she probably read Tolstoy and Dostoevsky growing up. So blame Dostoevsky! Yes, he does the same thing -- half of The Brothers Karamazov is characters giving long soliloquies about free will, moral authority, love, the evolution of Russian society, and whatever else Dostoevsky felt like rambling about. Okay, "rambling" is unfair -- a huge difference between Rand and Dostoevsky is that Rand spouted bullshit, while Dostoevsky spouted... well, brilliant philosophical ruminations or intellectual wankery, take your pick. At one point, an entire chapter is devoted to an allegorical tale by Ivan ("the atheist" -- more on this below) about Jesus returning to Earth, being imprisoned by the Spanish Inquisition, and being subjected to a long speech in which the Grand Inquisitor demands to know why he is interfering with his Church on Earth, when they are working to relieve man of the burden of free will he cruelly placed upon them. It's quite a cruel, witty, and articulate satire -- it also has nothing to do with the main story, only to do with clarifying Ivan's cynicism and non-atheism. Most of the time, characters go on and on like this for pages, with their audience saying not a word, or maybe occasionally interjecting a question. This is the author getting up on a soapbox, not advancing the plot. This may not be a flaw, if you don't regard "advancing the plot" as a necessary function of each chapter (and Dostoevsky definitely didn't).

Dostoevsky's Devil is more convincing than his atheist

Dostoevsky has an obvious blind spot: it's a very common blind spot among the devoutly religious. Dostoevsky regarded the existence of God to be so self-evident that he couldn't truly imagine an actual atheist. In his mind, atheists are people who know just like everyone else that God exists, but through contrariness, rebelliousness, dilettante philosophizing, or a wounded ego, they pretend to be scoffers. (Anyone who is an atheist has heard the "You know in your heart that God is real" argument plenty of times, usually followed by quoting Romans 14:11 if the believer is of a particularly sanctimonious variety.)

So Ivan, the "atheist," is really more of a skeptic. (Some descriptions of The Brothers Karamazov call him a "rationalist," but he often doesn't act all that rational). For all that he is supposedly an atheist, he spends most of his time thinking about (and being tormented by) God, religion, and the Devil. In fact, in one delirious episode, Ivan actually gets visited by the Devil, and has an argument about whether or not he's hallucinating him:

“Then even you don’t believe in God?” said Ivan, with a smile of hatred.

“What can I say?-that is, if you are in earnest-”

“Is there a God or not?” Ivan cried with the same savage intensity.

“Ah, then you are in earnest! My dear fellow, upon my word I don’t know.

There! I’ve said it now!”

“You don’t know, but you see God? No, you are not some one apart, you are

myself, you are I and nothing more! You are rubbish, you are my fancy!”

Even in his denial, it's clear that Ivan represents the straw-atheist that Dostoevsky believed all atheists to be: a man tormented by doubt who really wants to be convinced of God.

Now in fairness, Ivan is not stupid, malicious, or ignorant, and even when, earlier in the book, Father Zosima lumps atheists in with communists, anarchists, and other "evildoers," he speaks kindly of them and admits that some of them are good. Dostoevsky likewise seems to regard atheists benignly, but as wayward children.

Dostoevsky's devil is a perfectly devilish interlocutor, full of wit, humor, and malice so subtle it can slip right past if you're not paying attention. But it's yet another deviation from the story, interesting in terms of developing Ivan's character, and adding another stone to the observations Dostoevsky has piled up, but if you don't appreciate these little digressions for their own sake, you're not going to appreciate them at all.

The Trial

The thing is, you really should appreciate the digressions. (Or try.) Because Dostoevsky is a careful, thoughtful writer. His characters are larger than life archetypes, and hence like their grand speeches, their personalities are not really anything like what we'd likely encounter in reality. At the same time, viewed as illustrative caricatures, they are vivid, three-dimensional, and epic. Even the mean little bit-part players.

The trial is the culmination of everything there is to love and hate about this book. This isn't Law & Order: Dostoevsky describes the entire trial, and makes you listen to the entire arguments of the prosecutor and the defense. He was taking a few shots at the legal system here, and by making the prosecutor and the defense attorney both somewhat pompous, operatic fellows, and depicting the spiteful and romantic sentiments of the spectators, his commentary on the theatricality of the legal system is ironic in its contemporary relevance. But it's still a very careful, detailed (and, if your patience is running out, plodding) drama that hinges on the most minute details.

“I shall be told that he could not explain where he got the fifteen hundred that he had, and every one knew that he was without money before that night. Who knew it, pray? The prisoner has made a clear and unflinching statement of the source of that money, and if you will have it so, gentlemen of the jury, nothing can be more probable than that statement, and more consistent with the temper and spirit of the prisoner. The prosecutor is charmed with his own romance. A man of weak will, who had brought himself to take the three thousand so insultingly offered by his betrothed, could not, we are told, have set aside half and sewn it up, but would, even if he had done so, have unpicked it every two days and taken out a hundred, and so would have spent it all in a month. All this, you will remember, was put forward in a tone that brooked no contradiction. But what if the thing happened quite differently? What if you’ve been weaving a romance, and about quite a different kind of man? That’s just it, you have invented quite a different man!

What the Negative Reviewers Say

What do you think? If you've read all the teal deer above, then you can guess: Dostoevsky practically defines tl;dr. (According to the Wikipedia page, The Brothers Karamazov was intended it to be the first part of an epic story.)

You can't beat this one for succinctness:

I see your Dostoevsky and I raise you one Nabakov. What the heck is he talking about?

But you can always watch the movie

But not on Netflix. :(

There have been a number of Russian film versions made of The Brothers Karamazov, and there was a 1958 film starring Yul Brynner. Sadly, it's not available on Netflix, and while there are plenty of copies for sale on eBay, I just... was not feeling so inspired by the book that I was willing to pay money to see the movie. Maybe someday.

Verdict: Dostoevsky is someone you read for intellectual stimulation, not entertainment. (Well, not someone I would read for entertainment.) Is he a great writer? Yes. Is this book deep and meaningful? If you share Dostoevsky's religious views somewhat, then yes. But this is not the kind of book I can imagine loving and cherishing and wanting to reread for fun. I am glad to have read it, in the same way I'm glad to have passed a number of trials in my life that were good for me but not exactly experiences I'd want to repeat. Maybe Russian literature is just not for me; I'm happy to put The Brothers Karamazov back on its shelf and go read a nice space opera.

Although The Brothers Karamazov is one of the books on the 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die list, I did not read it for the books1001 challenge, so that honor is still awaiting someone else. ;) It's two months into the year and we've reviewed 48 of our 1001 books, so there are many, many books left to read. Please join us -- all you have to do is read and review one. (Though taking on more is encouraged!)