Book Review: John Tyler, the Accidental President, by Edward Crapol

POTUS #10: When "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too" turned into "His Accidency."

University of North Carolina Press, 2006, 344 pages

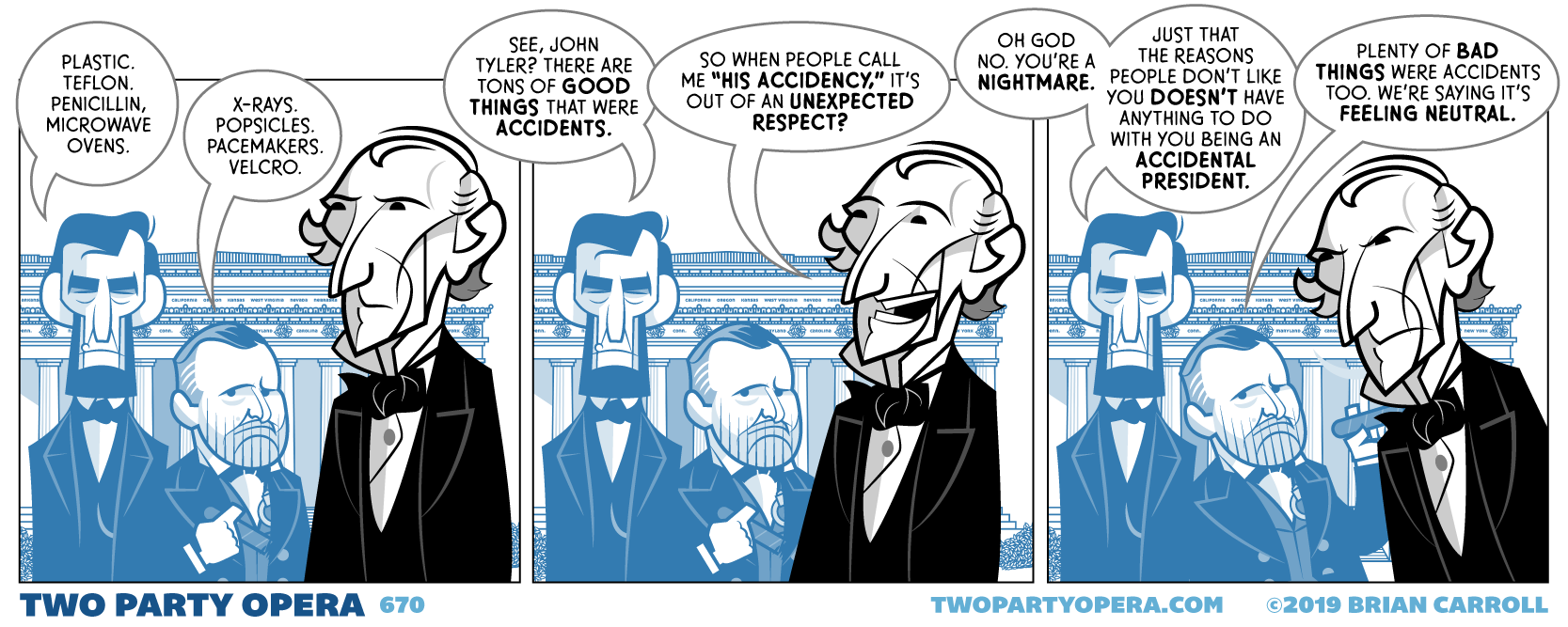

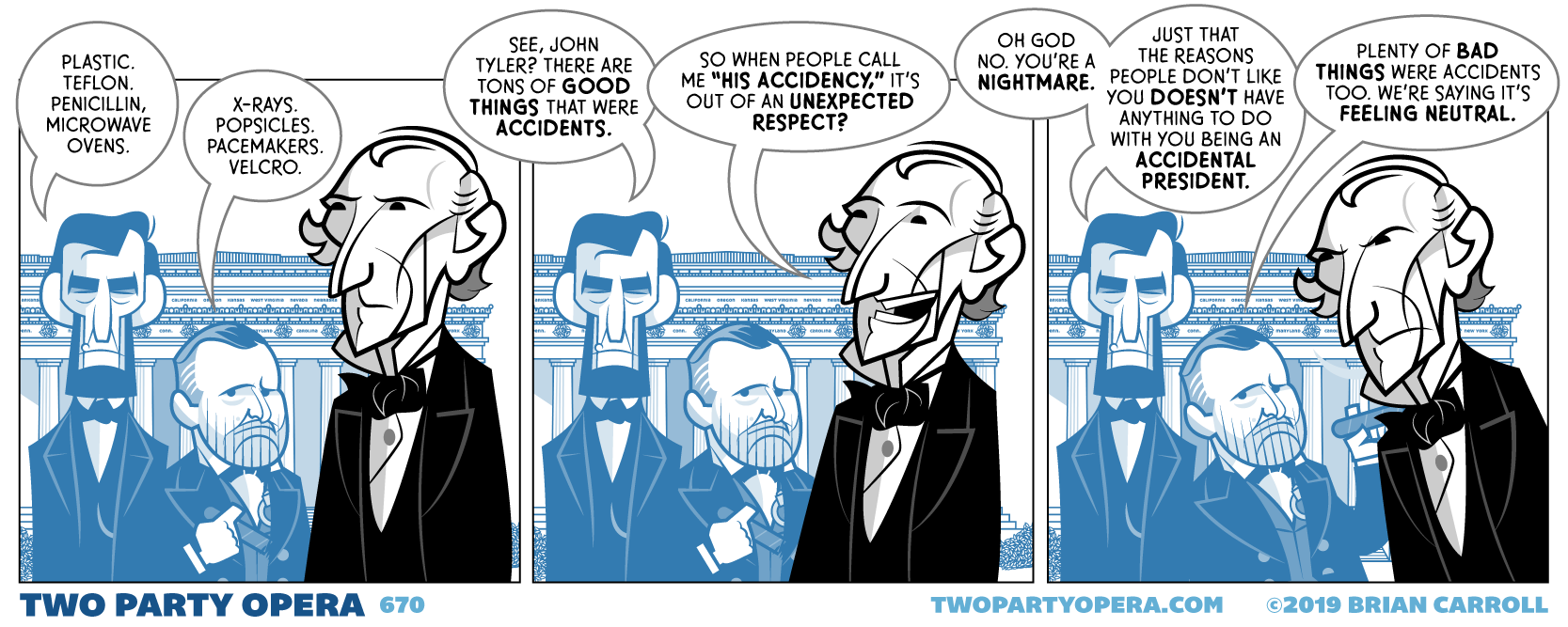

The first vice president to become president on the death of the incumbent, John Tyler (1790-1862) was derided by critics as "His Accidency." In this biography of the 10th president, Edward P. Crapol challenges depictions of Tyler as a die-hard advocate of states' rights, limited government, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. Instead, he argues, Tyler manipulated the Constitution to increase the executive power of the presidency. Crapol also highlights Tyler's faith in America's national destiny and his belief that boundless territorial expansion would preserve the Union as a slaveholding republic. When Tyler sided with the Confederacy in 1861, he was branded as America's "traitor" president for having betrayed the republic he once led.

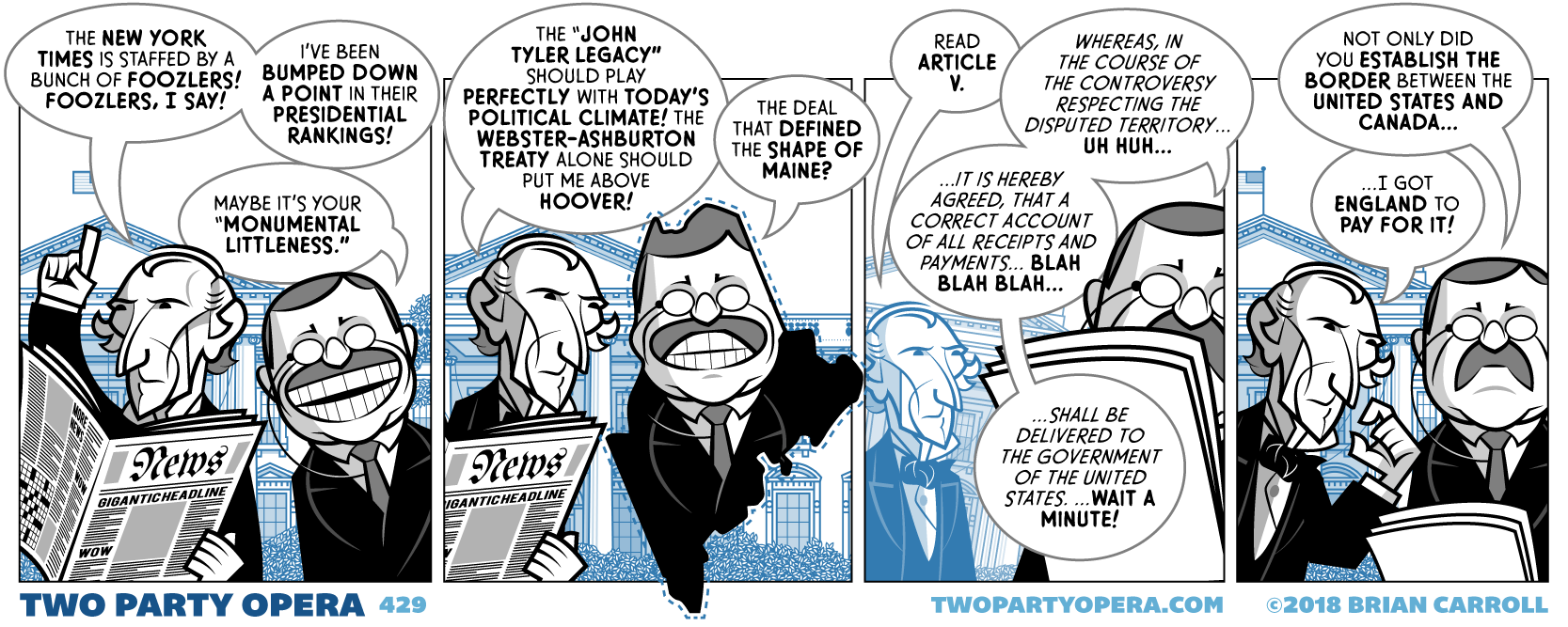

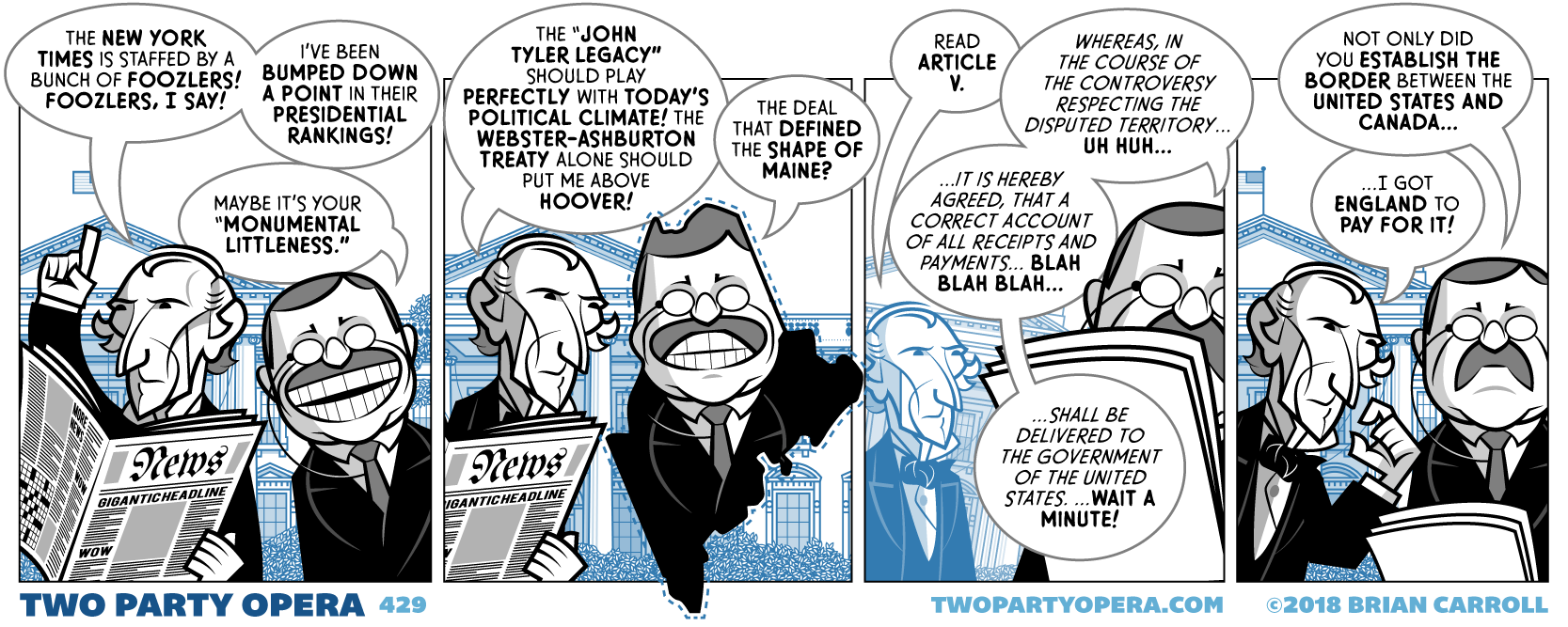

“He has been called a mediocre man; but this is unwarranted flattery. He was a politician of monumental littleness.”

- Theodore Roosevelt, writing about John Tyler

Let's face it folks, we're in the presidential doldrums here. There was a long string of C-listers between Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln that only the sort of person who memorizes presidents remembers. And yet, as I trudge through presidential biographies, I am once again rewarded. Not because John Tyler was fascinating (he wasn't) or because this biography of him was exceptional (it's okay), but because there are so many little details about both the man and his times that you'd never learn without reading about him at length that I feel my knowledge of American history continuing to be enriched. Reading presidential biographies in order is almost like diving into another season of that show you like on Netflix. Not every episode is a banger, but they're all building up to something. Look, here's Henry Clay again: what will he do this season? Martin Van Buren? So last season. Whoa, John Quincy Adams is still around! And that guy Lincoln keeps reappearing: I feel like he's going to be important eventually.

John Tyler was actually kind of interesting, in that he set a lot of precedents (most of them not particularly good) and Edward Crapol's rather dry but very readable biography paints him as a fairly capable if not exceptional politician. Teddy Roosevelt's criticism (which pissed off Tyler's descendants enough to provoke angry letters) was perhaps a little harsh.

(Tyler met Charles Dickens, who seemed to like him.)

“Popularity, I have always thought, may aptly be compared to a coquette-the more you woo her, the more apt is she to elude your embrace.”

- John Tyler

John Tyler was yet another wealthy Virginian born on a plantation, and Crapol skips quickly through his early political career. His father was Governor of Virginia, and John Tyler would be a congressman, governor, and senator himself. Initially a supporter of Andrew Jackson, he broke with the Democrats and Jackson on a number of issues, and somehow ended up joining Henry Clay's Whig Party, and somehow ended up on William Henry Harrison's ticket in 1836, and again in 1840. Crapol is light on the details of how he got there, because history is light on details: at the time, nobody really cared much about the VP slot.

The joke was on the Whigs. William Henry Harrison died a month into his term, making John Tyler the first vice president to assume the office of the presidency.

"His Accidency"

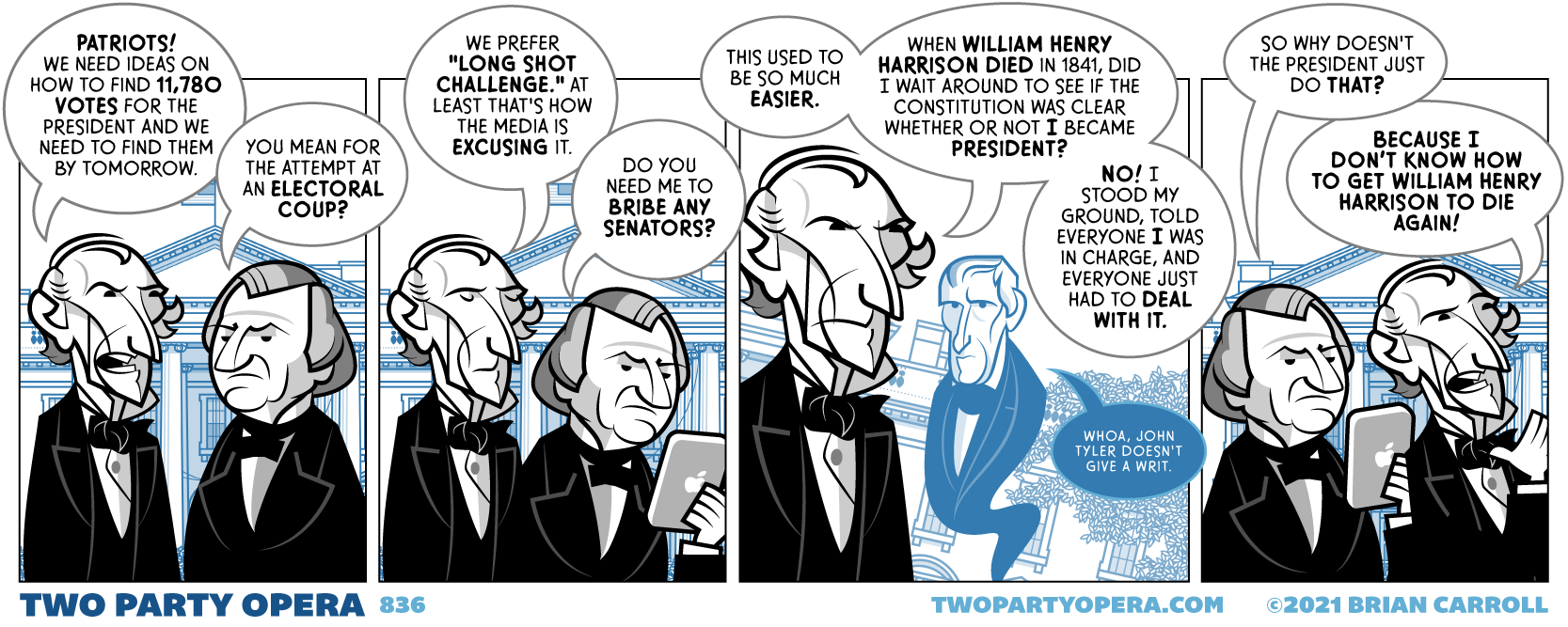

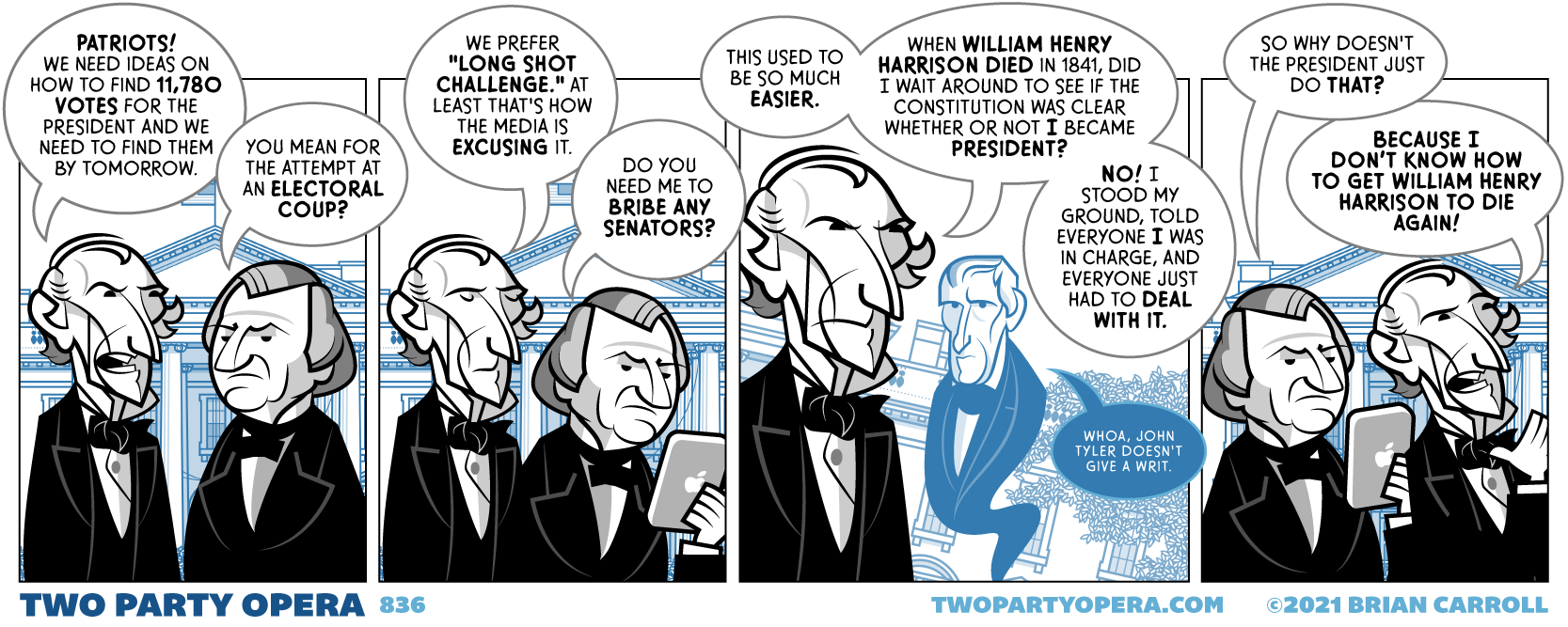

Since there was no precedent for a VP taking office, it wasn't entirely clear to Tyler's contemporaries what was supposed to happen next. The Constitution said that the vice president inherited the president's "powers and responsibilities," but it did not explicitly say the VP was to finish out the original president's term in office. Many congressman and senators thought the VP was only meant to be a placeholder until a "real" president was selected.

John Tyler begged to differ, and he simply stepped in, assumed the office, and made it clear that he was Harrison's replacement and he was going to stay. By doing so, he established the precedent which continues to this day.

Throughout his term, his detractors called him "His Accidency," and he sometimes received letters addressed to "Vice President/Acting President Tyler." He returned these unopened.

John Tyler, elected on the Whig ticket, promptly began vetoing every important piece of legislation the Whigs wanted, like the National Bank. The Whigs told him that Harrison had promised not to go against the majority opinion of his cabinet. Tyler said, "Yeah, no" and got rid of most of his cabinet.

Henry Clay was furious, called Tyler a traitor, and the Whigs expelled Tyler from the party. He became essentially a lame duck president almost immediately, and when he ran for reelection in 1844, he did so without a party.

In fairness, Tyler had never pretended to be in favor of the National Bank or a lot of other Whig causes. This is where having already read biographies of William Henry Harrison and Henry Clay was helpful, because Crapol only briefly discusses the origins of the Whig Party and their (brief) role in American history. The Whigs were never a cohesive party with a unified platform: they were mostly an anti-Jackson party, and in Henry Clay's mind, a "Get Henry Clay elected president" party. They were an uneasy alliance of pro-slavery Southerners and northern abolitionists, with an anti-Masonic fringe. The only thing they really all had in common was hating Andrew Jackson, and Jackson had been out of office for years now. Putting a conservative states-rights Southerner in the White House who immediately turned on them was a massive self-own for the Whigs, and they pretty much fell apart after this.

Tyler called himself a "Jeffersonian Democrat," but most politicians did by then. Like Jefferson, he proved rather flexible in his adherence to Constitutional principles, while fancying himself a strict constructionist.

The Whigs weren't the only ones he pissed off, and Tyler also had the distinction of being the first president to have impeachment proceedings initiated against him. (They didn't get very far, but he was quite stung by it; one trait of Tyler that Crapol makes clear is that while he wasn't an unusually egotistical man - for a politician - he was very concerned about his reputation and his historical legacy.)

During his (almost) four years in office, Tyler did actually prove to be rather assertive and while historians usually put him towards the bottom in presidential rankings, he did accomplish a few things.

He was the first president to expand America's influence into the Pacific. He never quite got the "window to the Pacific" he wanted (it would be his successor, Polk, who would acquire the west coast), but Crapol spends a chapter talking about Hawaii and its place in geopolitical strategy at the time. The Kingdom of Hawaii sent a number of envoys to Washington and Europe, trying to secure their sovereignty. The Hawaiian king did not know much about international politics, but he quickly grasped the need to get up to speed and tried to assemble a diplomatic corps, which included a prince who actually got an audience with Tyler. The Hawaiians skillfully played the "Britain" card - Tyler was an Anglophobe who had fought in the War of 1812, and the United States had reason to mistrust Britain's designs in the Pacific. Tyler tried, more or less, to expand the Monroe Doctrine to the entire Pacific. Throughout the 1840s, tensions with Britain were high and there was even the possibility of another war. At one point, a British naval commander actually annexed Hawaii (they later restored Hawaii's sovereignty, such as it was).

The British, for their part, found President Tyler frustrating to deal with. What they considered duplicitous dealings, Americans considered normal politics. Crapol describes a young Queen Victoria basically going "wtf?" at some of Tyler's communications, with her ministers trying to explain what he's going on about.

Tyler was also the first president to send a diplomatic envoy to China. He accurately saw the potential of such a vast market, one that currently only Britain had access to. He fortunately sent a very competent ambassador, because one of the most comical episodes Crapol describes is President Tyler writing a letter to the Emperor of China that read like the letters presidents wrote to Native American tribes: paternalistic and using the sort of language you'd use to explain things to a small child. His ambassador wisely held onto the letter until after he'd already established relationships in the Celestial court, and then he and the Chinese foreign minister had a good laugh over it.

The Princeton Disaster

In another precedent, Tyler was the first president to get married in office. His first wife, Letitia, passed away shortly after he took office. Tyler began wooing a wealthy New York socialite named Julia Gardiner who was thirty years younger than him. Miss Gardiner found him charming but reportedly reacted with shock and dismay when Tyler told her he actually wanted to marry her.

Then came the disaster of the USS Princeton.

In February 1844, President Tyler and a crowd of VIPs, including Julia Gardiner and her father, were cruising along the Potomac in the steamship Princeton. The Princeton periodically fired its big gun, the "Peacemaker," and everyone was having a grand time, a little drunk, and Tyler's Secretary of the Navy ordered the reluctant captain of the ship to fire the gun one more time.

Tyler was doing a bit of wooing with Julia down below decks when the Peacemaker exploded. It killed her father and several other people, including Tyler's Secretary of State and Secretary of the Navy. It was the largest number of government officials killed in a single disaster in U.S. history.

The Princeton disaster was a personal and political tragedy: Tyler knew his hopes of reelection had just been crippled with the loss of his most important allies. But, in the aftermath somehow Julia came around to accepting Tyler's marriage suit. People snickered, but by all accounts they were quite happy together. Julia really liked being First Lady, and she also, it turns out, really liked being mistress of a Southern plantation with slaves and even livery on her carriage.

Julia "I like older men and owning slaves" Gardiner Tyler.

By the time he died, Tyler had had fifteen children between his two wives. Incidentally, one of his grandchildren is still alive (as of 2022!). Yes, John Tyler, born in 1790, has a living grandson.

Like father, like son: Lyon Tyler married a woman 36 years younger than him and fathered kids into his 70s. Their children were born over 60 years after their grandfather, John Tyler, died.

While waging a losing campaign for reelection, Tyler's last act in office was negotiating the annexation of Texas. This was very important to him, and he would fight for his historical legacy and his role in bringing Texas into the union long after he left office. He would sometimes skirmish with his former Secretary of State (whom he unwisely chose to replace the one who died on the Princeton), John C. Calhoun, who tried to claim credit for annexing Texas, and also with former Texas President and later senator, Sam Houston, who thought Tyler tried to claim too much credit.

Acquiring Texas was a legitimate accomplishment, and fit with Tyler's vision of territorial expansion. The problem was, he did so essentially by executive fiat, ignoring inconvenient questions of Constitutionality (echoing Thomas Jefferson's legally dubious Louisiana Purchase in 1803). Some historians blame John Tyler for reviving Andrew Jackson's "imperial presidency" and setting a precedent for presidents expanding their powers, which needless to say, their successors never try to reduce.

Of course, annexing Texas also triggered the Mexican-American war, and because Texas entered the union as a slave state, it was a major blow against abolitionists, as John Tyler intended.

And Tyler was unquestionably a white supremacist. He opposed recognizing Haiti because Southerners were scared shitless by the Haitian revolution, and he later encouraged the Dominican Republic's revolt against Haiti, just because the Dominicans tried to emphasize how "not black" they were.

Tyler and Slavery

Tyler was, by the standards of his time, a "Southern moderate." Meaning, he was firmly pro-South and pro-slavery, and like many of his slave-owning predecessors, engaged in elaborate mental gymnastics to acknowledge that slavery was a nasty and brutal business and yet vital to the social and economic order.

As a senator, he was so sickened by the sight of slave markets in Washington, D.C. that he unsuccessfully tried to make them illegal (the markets, but not slavery) in the capital. As the divide between slave vs. non-slave states sharpened, he would advocate his "diffusion theory," which was basically that by allowing slavery in more states, it would become more "spread out" with relatively fewer people actually owning slaves, and eventually it would... go away or something.

It wasn't a particularly logical theory, but it demonstrated the cognitive dissonance many such Southerners wrestled with. Tyler seemed unaware that he was implicitly acknowledging the fundamental immorality of slavery as he offered apologetics and mitigation strategies to preserve slavery while promising that someday, it would not be an issue.

To his credit, Crapol is neither uncritical nor overly moralizing in his assessment of Tyler. He clearly recognizes slavery as a moral evil that Tyler was guilty of, and points out his hypocrisy and participation in the "peculiar institution," while also letting the man defend himself in his own words (and pointing out where his words did not match reality). For example, Tyler clearly thought of himself as a kind and benevolent master whose slaves were better off under his care. Yet some accounts by former slaves (which Crapol acknowledges are historically dubious) characterize him as ill-tempered and mean. He might not have been a flogging, raping sort of slavemaster, but he definitely sold "troublesome" slaves down the river to Deep South plantations. Crapol tells an anecdote about one of his favorite slaves, named Eliza Ann, whom Tyler mentioned needing to sell in order to cover his expenses as a new congressman. He was apparently trying to sell her to a family friend, but thence Eliza Ann disappears from history, and no one knows what ever happened to her. Tyler never mentions her again.

His wife, Julia, completely embraced the "peculiar institution." After they had left the White House, she briefly won acclaim throughout the South by writing a letter, published in newspapers, rebuking the Duchess of Sutherland and other English ladies who had criticized American slavery. Her response was basically "lol myob, aren't there lots of poor people in England, and what about the Irish?"

The Traitor President

After Tyler left the White House, he retired to his Virginia plantation. He called his estate "Sherwood Forest."

Sherwood Forest, the Tyler plantation.

His plan, like Jefferson's, was to live the life of an idyllic country gentleman (with slaves) and be a wise, respected elder statesman. But the country was moving towards disunion.

It took a long time for Tyler to fully come over to the secessionist side. When the Southern states held a conference in which they argued that the American law against African slave trading should be abolished, and the African slave trade reopened, Tyler opposed it. The Southerners argued that if trading in slaves was immoral, then slavery itself was immoral. Yup, they almost got it. Except they worked backwards and said that since slavery was a good thing, there was therefore nothing wrong with the African slave trade, and the law against it was just a slap in the face to Southerners. Tyler's influence helped quash this resolution, but he continued to struggle futilely to prevent a break-up. He continued to believe in the union almost until the end. After Lincoln was elected, Southerners threatened to secede if the U.S. didn't open up new slave territories to even the balance. Tyler was a member of the Southern delegation that met with Lincoln. It didn't go well, as Lincoln basically gave them an "Elections have consequences" speech.

After the failure of the Virginia Peace Conference, which some historians believe was just a stalling tactic that Tyler was complicit in (Crapol appears to share this view), it was Tyler's granddaughter Letitia who raised the Confederate flag for the first time in Charleston. John Tyler was elected to the newly-formed Confederate Congress, but he died before its first session.

Later, his mansion was sacked by Negro troops during the war, including some of his former slaves. His widow Julia was most put out.

John Tyler is the only U.S. President who served under the Confederacy, which blackened his place in history as the "traitor president." According to Crapol, he died in ignominy: no flags were lowered to half mast, there was no official recognition of his death from the White House. Only many years later was Congress ready to let bygones be bygones enough to grant his widow a small pension.

This is not the longest biography available about John Tyler: there is apparently a massive two-volume set that was supposed to be three volumes before the author got bored. But if you are trekking through presidential biographies and want some substantial but not massive coverage of each president, I think this one is a good, modern take on POTUS #10. Tyler won't be anyone's favorite president, but I appreciated seeing how he attempted to maneuver within the politics of his time. He definitely considered himself a moral and patriotic figure, and had enough of a conscience to perceive the cracks in his worldview, but not enough to change anything. He was neither brilliant nor incompetent, and his presidency, while not very accomplished, I don't think can fairly be called a complete failure, as he accomplished the few things that were probably within his reach. Except, you know, maybe preventing a civil war.

My complete list of book reviews.

University of North Carolina Press, 2006, 344 pages

The first vice president to become president on the death of the incumbent, John Tyler (1790-1862) was derided by critics as "His Accidency." In this biography of the 10th president, Edward P. Crapol challenges depictions of Tyler as a die-hard advocate of states' rights, limited government, and a strict interpretation of the Constitution. Instead, he argues, Tyler manipulated the Constitution to increase the executive power of the presidency. Crapol also highlights Tyler's faith in America's national destiny and his belief that boundless territorial expansion would preserve the Union as a slaveholding republic. When Tyler sided with the Confederacy in 1861, he was branded as America's "traitor" president for having betrayed the republic he once led.

“He has been called a mediocre man; but this is unwarranted flattery. He was a politician of monumental littleness.”

- Theodore Roosevelt, writing about John Tyler

Let's face it folks, we're in the presidential doldrums here. There was a long string of C-listers between Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln that only the sort of person who memorizes presidents remembers. And yet, as I trudge through presidential biographies, I am once again rewarded. Not because John Tyler was fascinating (he wasn't) or because this biography of him was exceptional (it's okay), but because there are so many little details about both the man and his times that you'd never learn without reading about him at length that I feel my knowledge of American history continuing to be enriched. Reading presidential biographies in order is almost like diving into another season of that show you like on Netflix. Not every episode is a banger, but they're all building up to something. Look, here's Henry Clay again: what will he do this season? Martin Van Buren? So last season. Whoa, John Quincy Adams is still around! And that guy Lincoln keeps reappearing: I feel like he's going to be important eventually.

John Tyler was actually kind of interesting, in that he set a lot of precedents (most of them not particularly good) and Edward Crapol's rather dry but very readable biography paints him as a fairly capable if not exceptional politician. Teddy Roosevelt's criticism (which pissed off Tyler's descendants enough to provoke angry letters) was perhaps a little harsh.

(Tyler met Charles Dickens, who seemed to like him.)

“Popularity, I have always thought, may aptly be compared to a coquette-the more you woo her, the more apt is she to elude your embrace.”

- John Tyler

John Tyler was yet another wealthy Virginian born on a plantation, and Crapol skips quickly through his early political career. His father was Governor of Virginia, and John Tyler would be a congressman, governor, and senator himself. Initially a supporter of Andrew Jackson, he broke with the Democrats and Jackson on a number of issues, and somehow ended up joining Henry Clay's Whig Party, and somehow ended up on William Henry Harrison's ticket in 1836, and again in 1840. Crapol is light on the details of how he got there, because history is light on details: at the time, nobody really cared much about the VP slot.

The joke was on the Whigs. William Henry Harrison died a month into his term, making John Tyler the first vice president to assume the office of the presidency.

"His Accidency"

Since there was no precedent for a VP taking office, it wasn't entirely clear to Tyler's contemporaries what was supposed to happen next. The Constitution said that the vice president inherited the president's "powers and responsibilities," but it did not explicitly say the VP was to finish out the original president's term in office. Many congressman and senators thought the VP was only meant to be a placeholder until a "real" president was selected.

John Tyler begged to differ, and he simply stepped in, assumed the office, and made it clear that he was Harrison's replacement and he was going to stay. By doing so, he established the precedent which continues to this day.

Throughout his term, his detractors called him "His Accidency," and he sometimes received letters addressed to "Vice President/Acting President Tyler." He returned these unopened.

John Tyler, elected on the Whig ticket, promptly began vetoing every important piece of legislation the Whigs wanted, like the National Bank. The Whigs told him that Harrison had promised not to go against the majority opinion of his cabinet. Tyler said, "Yeah, no" and got rid of most of his cabinet.

Henry Clay was furious, called Tyler a traitor, and the Whigs expelled Tyler from the party. He became essentially a lame duck president almost immediately, and when he ran for reelection in 1844, he did so without a party.

In fairness, Tyler had never pretended to be in favor of the National Bank or a lot of other Whig causes. This is where having already read biographies of William Henry Harrison and Henry Clay was helpful, because Crapol only briefly discusses the origins of the Whig Party and their (brief) role in American history. The Whigs were never a cohesive party with a unified platform: they were mostly an anti-Jackson party, and in Henry Clay's mind, a "Get Henry Clay elected president" party. They were an uneasy alliance of pro-slavery Southerners and northern abolitionists, with an anti-Masonic fringe. The only thing they really all had in common was hating Andrew Jackson, and Jackson had been out of office for years now. Putting a conservative states-rights Southerner in the White House who immediately turned on them was a massive self-own for the Whigs, and they pretty much fell apart after this.

Tyler called himself a "Jeffersonian Democrat," but most politicians did by then. Like Jefferson, he proved rather flexible in his adherence to Constitutional principles, while fancying himself a strict constructionist.

The Whigs weren't the only ones he pissed off, and Tyler also had the distinction of being the first president to have impeachment proceedings initiated against him. (They didn't get very far, but he was quite stung by it; one trait of Tyler that Crapol makes clear is that while he wasn't an unusually egotistical man - for a politician - he was very concerned about his reputation and his historical legacy.)

During his (almost) four years in office, Tyler did actually prove to be rather assertive and while historians usually put him towards the bottom in presidential rankings, he did accomplish a few things.

He was the first president to expand America's influence into the Pacific. He never quite got the "window to the Pacific" he wanted (it would be his successor, Polk, who would acquire the west coast), but Crapol spends a chapter talking about Hawaii and its place in geopolitical strategy at the time. The Kingdom of Hawaii sent a number of envoys to Washington and Europe, trying to secure their sovereignty. The Hawaiian king did not know much about international politics, but he quickly grasped the need to get up to speed and tried to assemble a diplomatic corps, which included a prince who actually got an audience with Tyler. The Hawaiians skillfully played the "Britain" card - Tyler was an Anglophobe who had fought in the War of 1812, and the United States had reason to mistrust Britain's designs in the Pacific. Tyler tried, more or less, to expand the Monroe Doctrine to the entire Pacific. Throughout the 1840s, tensions with Britain were high and there was even the possibility of another war. At one point, a British naval commander actually annexed Hawaii (they later restored Hawaii's sovereignty, such as it was).

The British, for their part, found President Tyler frustrating to deal with. What they considered duplicitous dealings, Americans considered normal politics. Crapol describes a young Queen Victoria basically going "wtf?" at some of Tyler's communications, with her ministers trying to explain what he's going on about.

Tyler was also the first president to send a diplomatic envoy to China. He accurately saw the potential of such a vast market, one that currently only Britain had access to. He fortunately sent a very competent ambassador, because one of the most comical episodes Crapol describes is President Tyler writing a letter to the Emperor of China that read like the letters presidents wrote to Native American tribes: paternalistic and using the sort of language you'd use to explain things to a small child. His ambassador wisely held onto the letter until after he'd already established relationships in the Celestial court, and then he and the Chinese foreign minister had a good laugh over it.

The Princeton Disaster

In another precedent, Tyler was the first president to get married in office. His first wife, Letitia, passed away shortly after he took office. Tyler began wooing a wealthy New York socialite named Julia Gardiner who was thirty years younger than him. Miss Gardiner found him charming but reportedly reacted with shock and dismay when Tyler told her he actually wanted to marry her.

Then came the disaster of the USS Princeton.

In February 1844, President Tyler and a crowd of VIPs, including Julia Gardiner and her father, were cruising along the Potomac in the steamship Princeton. The Princeton periodically fired its big gun, the "Peacemaker," and everyone was having a grand time, a little drunk, and Tyler's Secretary of the Navy ordered the reluctant captain of the ship to fire the gun one more time.

Tyler was doing a bit of wooing with Julia down below decks when the Peacemaker exploded. It killed her father and several other people, including Tyler's Secretary of State and Secretary of the Navy. It was the largest number of government officials killed in a single disaster in U.S. history.

The Princeton disaster was a personal and political tragedy: Tyler knew his hopes of reelection had just been crippled with the loss of his most important allies. But, in the aftermath somehow Julia came around to accepting Tyler's marriage suit. People snickered, but by all accounts they were quite happy together. Julia really liked being First Lady, and she also, it turns out, really liked being mistress of a Southern plantation with slaves and even livery on her carriage.

Julia "I like older men and owning slaves" Gardiner Tyler.

By the time he died, Tyler had had fifteen children between his two wives. Incidentally, one of his grandchildren is still alive (as of 2022!). Yes, John Tyler, born in 1790, has a living grandson.

Like father, like son: Lyon Tyler married a woman 36 years younger than him and fathered kids into his 70s. Their children were born over 60 years after their grandfather, John Tyler, died.

While waging a losing campaign for reelection, Tyler's last act in office was negotiating the annexation of Texas. This was very important to him, and he would fight for his historical legacy and his role in bringing Texas into the union long after he left office. He would sometimes skirmish with his former Secretary of State (whom he unwisely chose to replace the one who died on the Princeton), John C. Calhoun, who tried to claim credit for annexing Texas, and also with former Texas President and later senator, Sam Houston, who thought Tyler tried to claim too much credit.

Acquiring Texas was a legitimate accomplishment, and fit with Tyler's vision of territorial expansion. The problem was, he did so essentially by executive fiat, ignoring inconvenient questions of Constitutionality (echoing Thomas Jefferson's legally dubious Louisiana Purchase in 1803). Some historians blame John Tyler for reviving Andrew Jackson's "imperial presidency" and setting a precedent for presidents expanding their powers, which needless to say, their successors never try to reduce.

Of course, annexing Texas also triggered the Mexican-American war, and because Texas entered the union as a slave state, it was a major blow against abolitionists, as John Tyler intended.

And Tyler was unquestionably a white supremacist. He opposed recognizing Haiti because Southerners were scared shitless by the Haitian revolution, and he later encouraged the Dominican Republic's revolt against Haiti, just because the Dominicans tried to emphasize how "not black" they were.

Tyler and Slavery

Tyler was, by the standards of his time, a "Southern moderate." Meaning, he was firmly pro-South and pro-slavery, and like many of his slave-owning predecessors, engaged in elaborate mental gymnastics to acknowledge that slavery was a nasty and brutal business and yet vital to the social and economic order.

As a senator, he was so sickened by the sight of slave markets in Washington, D.C. that he unsuccessfully tried to make them illegal (the markets, but not slavery) in the capital. As the divide between slave vs. non-slave states sharpened, he would advocate his "diffusion theory," which was basically that by allowing slavery in more states, it would become more "spread out" with relatively fewer people actually owning slaves, and eventually it would... go away or something.

It wasn't a particularly logical theory, but it demonstrated the cognitive dissonance many such Southerners wrestled with. Tyler seemed unaware that he was implicitly acknowledging the fundamental immorality of slavery as he offered apologetics and mitigation strategies to preserve slavery while promising that someday, it would not be an issue.

To his credit, Crapol is neither uncritical nor overly moralizing in his assessment of Tyler. He clearly recognizes slavery as a moral evil that Tyler was guilty of, and points out his hypocrisy and participation in the "peculiar institution," while also letting the man defend himself in his own words (and pointing out where his words did not match reality). For example, Tyler clearly thought of himself as a kind and benevolent master whose slaves were better off under his care. Yet some accounts by former slaves (which Crapol acknowledges are historically dubious) characterize him as ill-tempered and mean. He might not have been a flogging, raping sort of slavemaster, but he definitely sold "troublesome" slaves down the river to Deep South plantations. Crapol tells an anecdote about one of his favorite slaves, named Eliza Ann, whom Tyler mentioned needing to sell in order to cover his expenses as a new congressman. He was apparently trying to sell her to a family friend, but thence Eliza Ann disappears from history, and no one knows what ever happened to her. Tyler never mentions her again.

His wife, Julia, completely embraced the "peculiar institution." After they had left the White House, she briefly won acclaim throughout the South by writing a letter, published in newspapers, rebuking the Duchess of Sutherland and other English ladies who had criticized American slavery. Her response was basically "lol myob, aren't there lots of poor people in England, and what about the Irish?"

The Traitor President

After Tyler left the White House, he retired to his Virginia plantation. He called his estate "Sherwood Forest."

Sherwood Forest, the Tyler plantation.

His plan, like Jefferson's, was to live the life of an idyllic country gentleman (with slaves) and be a wise, respected elder statesman. But the country was moving towards disunion.

It took a long time for Tyler to fully come over to the secessionist side. When the Southern states held a conference in which they argued that the American law against African slave trading should be abolished, and the African slave trade reopened, Tyler opposed it. The Southerners argued that if trading in slaves was immoral, then slavery itself was immoral. Yup, they almost got it. Except they worked backwards and said that since slavery was a good thing, there was therefore nothing wrong with the African slave trade, and the law against it was just a slap in the face to Southerners. Tyler's influence helped quash this resolution, but he continued to struggle futilely to prevent a break-up. He continued to believe in the union almost until the end. After Lincoln was elected, Southerners threatened to secede if the U.S. didn't open up new slave territories to even the balance. Tyler was a member of the Southern delegation that met with Lincoln. It didn't go well, as Lincoln basically gave them an "Elections have consequences" speech.

After the failure of the Virginia Peace Conference, which some historians believe was just a stalling tactic that Tyler was complicit in (Crapol appears to share this view), it was Tyler's granddaughter Letitia who raised the Confederate flag for the first time in Charleston. John Tyler was elected to the newly-formed Confederate Congress, but he died before its first session.

Later, his mansion was sacked by Negro troops during the war, including some of his former slaves. His widow Julia was most put out.

John Tyler is the only U.S. President who served under the Confederacy, which blackened his place in history as the "traitor president." According to Crapol, he died in ignominy: no flags were lowered to half mast, there was no official recognition of his death from the White House. Only many years later was Congress ready to let bygones be bygones enough to grant his widow a small pension.

This is not the longest biography available about John Tyler: there is apparently a massive two-volume set that was supposed to be three volumes before the author got bored. But if you are trekking through presidential biographies and want some substantial but not massive coverage of each president, I think this one is a good, modern take on POTUS #10. Tyler won't be anyone's favorite president, but I appreciated seeing how he attempted to maneuver within the politics of his time. He definitely considered himself a moral and patriotic figure, and had enough of a conscience to perceive the cracks in his worldview, but not enough to change anything. He was neither brilliant nor incompetent, and his presidency, while not very accomplished, I don't think can fairly be called a complete failure, as he accomplished the few things that were probably within his reach. Except, you know, maybe preventing a civil war.

My complete list of book reviews.