Book Review: Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), by Victor Hugo

A historical epic of medieval Paris, it's really a gothic fantasy, and it's not really about Quasimodo and Esmeralda.

First published (in French) in 1831.

English translation by Isabel F. Hapgood published in 1881. Approx. 185,000 words. Available for free at Project Gutenberg.

Set amid the riot, intrigue, and pageantry of medieval Paris, Victor Hugo's masterful tale of heroism and adventure has been a perennial favorite since its first publication in 1831. It is the story of Quasimodo, the deformed bell-ringer of the Notre Dame Cathedral, who falls in love with the beautiful gypsy Esmeralda. When Esmeralda is condemned as a witch by Claude Frollo, the tormented archdeacon who lusts after her, Quasimodo attempts to save her; but his intentions are misunderstood. Written with a profound sense of tragic irony, Hugo's powerful historical romance remains one of the most thrilling stories of all time.

The proper title of Victor Hugo's novel is Notre-Dame de Paris. Contrary to what every movie based on the book would lead you to believe (see below), it is primarily about Paris and the cathedral and medieval French society, against which backdrop a story of obsessive lust, naive love, and betrayal unfolds. At some point an English translator decided that Quasimodo was the main character, and so forever after Hugo's novel has been translated into English as "The Hunchback of Notre Dame." Most of the film adaptations (starting with the 1923 Lon Chaney one) cast it as a gothic horror piece, thus associating the "hunchback" reference even more strongly with the novel. But Lon Chaney and Disney cartoons notwithstanding, this story is as much about the city of Paris and Our Lady of Paris as it as about a hunchback and a gypsy dancer.

Written almost 200 years ago, Notre-Dame de Paris is set in 1482. Victor Hugo was writing a historical novel set 350 years before his time. He was obviously fascinated by the history and architecture of medieval Paris (as is alluded to in the foreword), and boy does he want to tell you about it.

The novel begins with the Epiphany and the Feast of Fools in January, 1482. Among the events being held that day in the city of Paris is a Mystery play at the Palais de Justice. Parisians flock to the Palais to be entertained, and here we see our first glimpse of the classes mingling: academicians, bourgeois, clergy, and beggars all throng about in the Palais clamoring for the play to begin. They soon become quite rowdy, and the scene proceeds in a slow but humorous fashion, spanning several chapters. The first main character to whom we are introduced is Pierre Gringoire, a hapless, penniless playwrite. He's waiting for the Archdeacon to show up to see his masterpiece and become his patron. The restless crowd threatens to lynch Gringoire and his cast if they don't start immediately, and everything degenerates into chaos and comedy.

The humor sneaks up on you, as it does throughout the book. Poor Gringoire is alternately trying to flirt with pretty girls, elicit praise for his play, get the crowd's attention, and keep from being lynched. The description of the play he's trying to put on is hilarious-he has grand artistic pretensions and he wrote this absurd monstrosity, rich with classical allusions and sucking up to current political figures, and he presents it to a mob that just wants to be entertained, and will be as entertained by hanging the actors as by watching them perform.

Quasimodo doesn't show up until Chapter 5, when he wins a "grimacing contest" and is elected as the Pope of Fools:

Or rather, his whole person was a grimace. A huge head, bristling with red hair; between his shoulders an enormous hump, a counterpart perceptible in front; a system of thighs and legs so strangely astray that they could touch each other only at the knees, and, viewed from the front, resembled the crescents of two scythes joined by the handles; large feet, monstrous hands; and, with all this deformity, an indescribable and redoubtable air of vigor, agility, and courage,--strange exception to the eternal rule which wills that force as well as beauty shall be the result of harmony. Such was the pope whom the fools had just chosen for themselves.

One would have pronounced him a giant who had been broken and badly put together again.

When this species of cyclops appeared on the threshold of the chapel, motionless, squat, and almost as broad as he was tall; squared on the base, as a great man says; with his doublet half red, half violet, sown with silver bells, and, above all, in the perfection of his ugliness, the populace recognized him on the instant, and shouted with one voice,--

"'Tis Quasimodo, the bellringer! 'tis Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre-Dame! Quasimodo, the one-eyed! Quasimodo, the bandy-legged! Noel! Noel!"

While Quasimodo is being carried through the streets by the raucous crowd, Gringoire is looking for a place to sleep, now that his play has been ruined and he hasn't been paid. Stumbling through the streets, he witnesses the beautiful gypsy dancer Esmeralda, who is subsequently almost abducted by Quasimodo before being rescued by a handsome captain of the guard named Phoebus.

Gringoire ends up taking a wrong turn and finds himself in the bad part of town, confronted by the King of Vagabonds and the Thieves' Court, where he is sentenced to be hanged. He's saved at the last minute by the sudden appearance of Esmeralda, who agrees to "marry" him in order to spare him from being hanged.

Gringoire, is easily the most amusing character in the book. He gets an awful lot of chapters even though his impact on the story is minimal. He loses no time getting over his homelessness and near-death experience as soon as he thinks he's going to score.

The gypsy's corsage slipped through his hands like the skin of an eel. She bounded from one end of the tiny room to the other, stooped down, and raised herself again, with a little poniard in her hand, before Gringoire had even had time to see whence the poniard came; proud and angry, with swelling lips and inflated nostrils, her cheeks as red as an api apple, and her eyes darting lightnings. At the same time, the white goat placed itself in front of her, and presented to Gringoire a hostile front, bristling with two pretty horns, gilded and very sharp. All this took place in the twinkling of an eye.

The dragon-fly had turned into a wasp, and asked nothing better than to sting.

Our philosopher was speechless, and turned his astonished eyes from the goat to the young girl. "Holy Virgin!" he said at last, when surprise permitted him to speak, "here are two hearty dames!"

The gypsy broke the silence on her side.

"You must be a very bold knave!"

"Pardon, mademoiselle," said Gringoire, with a smile. "But why did you take me for your husband?"

"Should I have allowed you to be hanged?"

"So," said the poet, somewhat disappointed in his amorous hopes. "You had no other idea in marrying me than to save me from the gibbet?"

"And what other idea did you suppose that I had?"

At this point, Hugo has now introduced all the main characters and established the plot elements that will drive the rest of the story, although much of what is actually going on is not yet apparent to the reader. Here I was forming a favorable impression of the book, as I love an author who's got a knack for putting everything together nicely, and I'm okay with taking your time to develop the story if it's engaging along the way.

And right here is where Hugo decides to walk away from the story for a while to deliver some huge infodumps.

My research, let me show you it

In Part Three, the author stops the story entirely to spend a couple of chapters telling us all about Paris and Notre-Dame. Victor Hugo researched the history of Paris and how it grew from a little island settlement on the Seine to expand across the Left and Right Banks, and how all the neighborhoods, fortifications, walls, buildings, and architectural styles that grew up in successive layers came to be, as well as the medieval division between Town, City, and University.

Needless to say, this is something few modern writers could get away with. Contemporary readers are not fond of infodumps like this, especially when they completely interrupt the flow of the story. I am not fond of infodumps like this; it was a chore to plow through 50 pages about every wall and gate and bridge in Paris.

However, if you are a writer who has an interest in writing medieval fantasy, I don't think you could do better than read Notre-Dame de Paris to get a great big dose of verisimilitude about what medieval cities actually looked like. Hugo carefully strips away the layers of Paris from its earliest foundations to the city as it was at the time about which he is writing, and then comments on the city as it was at the time he was writing (the 19th century), with many lamentations about the poor job modern architects were doing in preserving the old facades and stonework.

The Paris of the present day has then, no general physiognomy. It is a collection of specimens of many centuries, and the finest have disappeared. The capital grows only in houses, and what houses! At the rate at which Paris is now proceeding, it will renew itself every fifty years.

Thus the historical significance of its architecture is being effaced every day. Monuments are becoming rarer and rarer, and one seems to see them gradually engulfed, by the flood of houses. Our fathers had a Paris of stone; our sons will have one of plaster.

Indeed, you can see Hugo's medieval Paris echoed in many fantasy novels. When I read about the University, the Town, and the City, I immediately thought of Patrick Rothfuss's The Name of the Wind; if Rothfuss did not read Notre-Dame de Paris himself, he was certainly influenced by other historical and fantasy writers who had. Likewise, the Kingdom of Argotiers is the model for every "Thieves Guild" written since.

Notre-Dame de Paris is Epic

So after being thrown out of the story a bit by the long exposition, it took me a while to get back into the story, but once I did, I began to fall under its spell. Notre-Dame de Paris is one of those books that requires patience: it is rewarding only after you've read hundreds of pages of set-up. If that sounds like too much to ask from a modern reader, then it's a shame, but I'm glad I did stick with it because this was one of my "assigned" books from the books1001 challenge. Most people (who have not read the book) think "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" is about the mistreated outcast Quasimodo rescuing Esmeralda from the evil Claude Frollo. But those are really only part of a long chain of events that invoke irony, tragedy, humor and pathos, connecting beggars on the streets of Paris to Louis XI. In this chain reaction leading to its dramatic climax, Quasimodo and Esmeralda are only catalysts. The two of them are significant characters, but they are not really "main" characters any more than Pierre Gringoire and Claude Frollo and Captain Phoebus, all of whom get about as much page space, and towering over all of them, present on nearly every page, is Notre-Dame de Paris, the true main character.

Notre-Dame de Paris is a fantasy novel

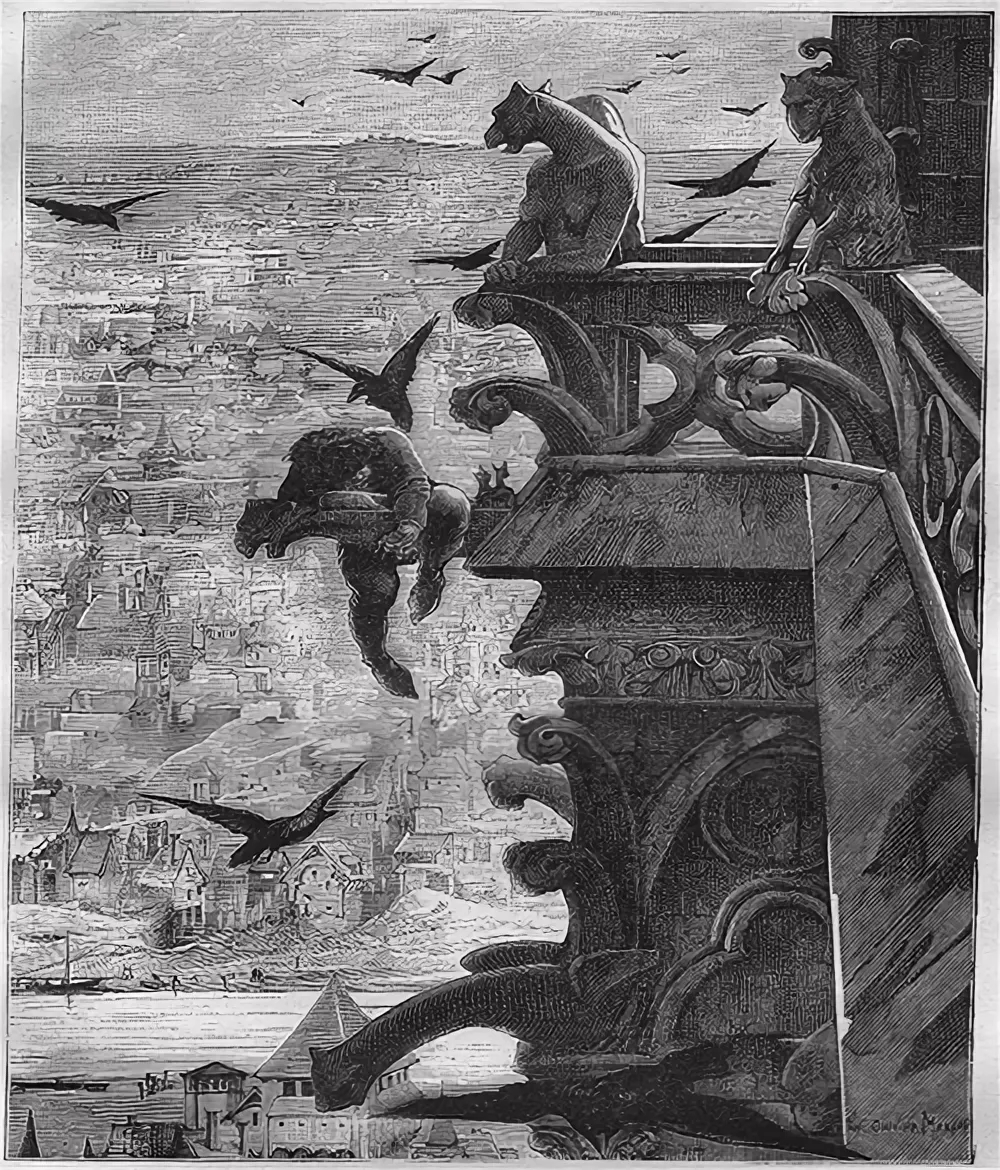

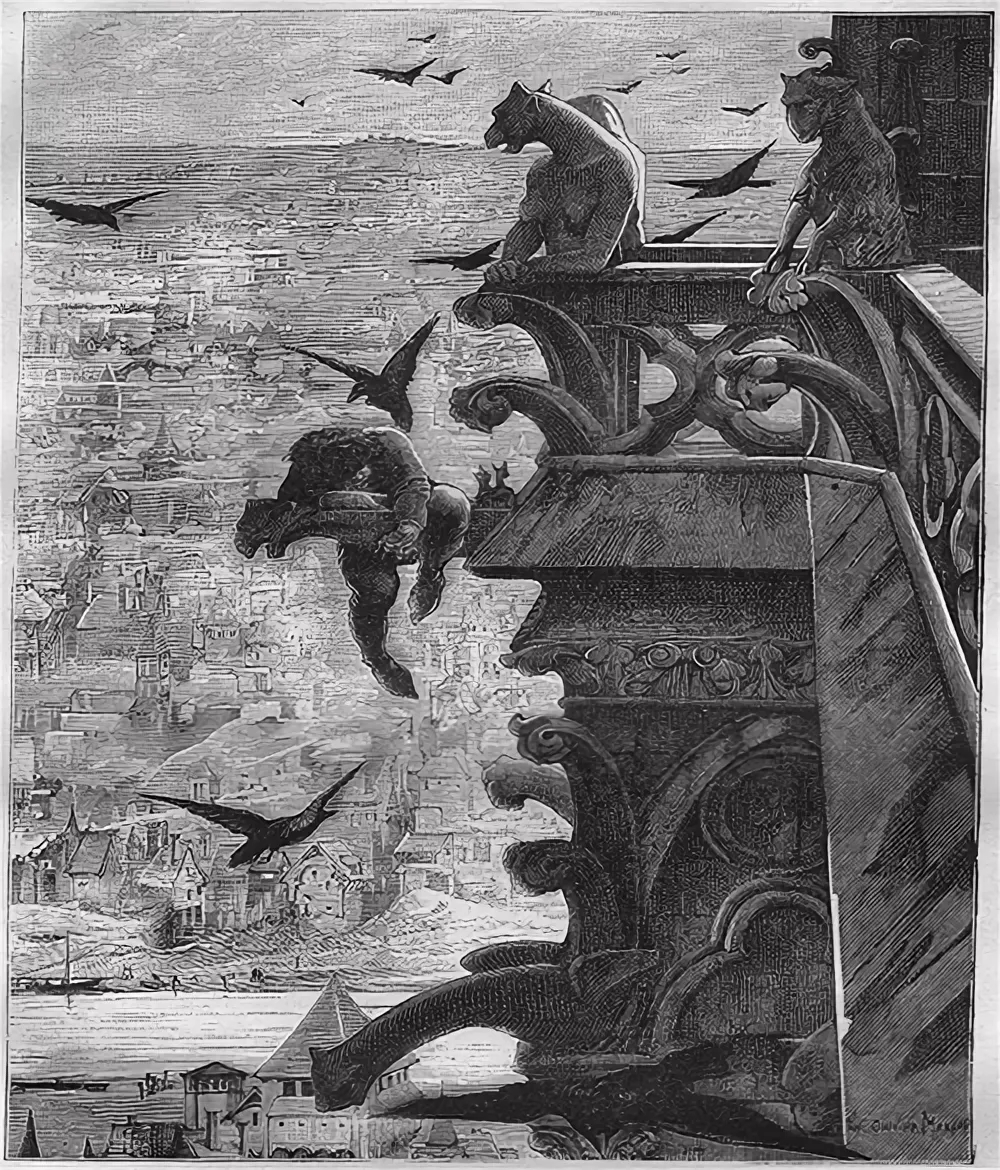

Seriously. This is a medieval fantasy novel, it just doesn't have any literal magic or literally supernatural creatures. You've got a medieval city described in great detail. The main characters include thieves, clerics, knights, and bards, a monstrous hero with superhuman strength, and a beautiful damsel in distress with an animal companion. The action takes place in cathedrals, back alleys, palaces, inns, and dungeons. There are assassins and brigands and nobles, and while Claude Frollo, who is called a sorcerer by the townspeople, may not actually cast spells, he studies alchemy and hermeticism and astrology, and the description of his laboratory and his books is as complete a description of a wizard's tower as any fantasy novelist has written. There's romance and political intrigue, pitched battles between peasant footsoldiers and cavalry and archers, escapes through secret passages, and a siege repelled by a monster with rocks and molten lead.

If you don't demand elves and dragons, this book isn't missing anything else to be classified as a fantasy epic.

It's also funnier than you think

It took me a while to realize this. Victor Hugo is being funny. You can talk about your dry British humor, but Hugo's wit is as arid as it is acid. Notre Dame de Paris is full of jokes which are reminiscent of Jane Smiley's observation about French novelists in Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel, that whereas English novelists often presented an idealized version of England, French novelists tended to portray France as a vipers' nest.

In every chapter from the misadventures of Pierre Gringoire to the most benevolent sagacity of his Majesty Louis XI, Hugo inserts some wry aside. And his habit of writing long blocks of expository text reveals itself as his way of taking his time in setting up a punchline.

"Master Olivier, princes who reign over great siegneuries, as kings and emperors, ought not to allow extravagance to creep into their households, for 'tis a fire that will spread thence into the provinces....

(Louis XI goes on ranting for several paragraphs about increasing expenses.)

He stopped, out of breath, then resumed with vehemence.

"I see all around me nothing but people who are getting fat on my leanness. You are sucking money from my every pore!"

Everyone remained silent. It was one of his fits of passion which had to run its course.

This section goes on for a couple of pages with Louis XI's comptroller itemizing all his expenses and the king complaining about everything from the cost of clothes to the number of chefs on his staff.

Then:

"Divers partitions, planks, and trapdoors, for the safe-keeping of lions at the Hotel Saint-Paul, twenty-two livres."

"They are costly beasts!" said Louis XI. "But no matter; it's a fair piece of royal magnificence. There is a great red lion which I am very fond of for his engaging ways. Have you seen him, Master Guillaume? Princes should have those remarkable animals. We kings ought to have lions for our dogs and tigers for our cats. The great beasts befit a crown. In the time of the pagans of Jupiter, when the people offered up at the holy places a hundred oxen and a hundred sheep, the emperor gave a hundred lions and a hundred eagles. That was very fierce and noble. The kings of France have always had those roarings about their throne. Nevertheless, people must do me the justice to say that I spend less money in that way than my predecessors, and that I am exceedingly moderate on the score of lions, bears, elephants, and leopards."

The right translation

Notre-Dame De Paris has been translated into English many times. I had not previously given much thought to hunting around for the best version of a novel with multiple translations.

I started reading the Project Gutenberg version, because it was free. This was the 1888 Isabel Hapgood translation. However, thanks to my ereader needing to be replaced, I was less than halfway through when I checked out a paperback from the library to finish it. This turned out to be the 1964 Walter J. Cobb translation.

This translation was much better. The English was more contemporary, the translation idiomatic but smooth, and suddenly reading this book was a much more pleasant experience. It's very close to the Hapgood translation, but compare this passage to the Hapgood translation of the same passage above:

Rather his whole person was a grimace. His enormous head bristled with red hair; between his shoulders was an enormous hump, counterbalanced by a protuberance in front; he had a framework of thighs and legs so strangely askew that they could touch only at the knees, and, seen from the front, resembled two sickles joined together at the handles. The feet were huge; the hands monstrous. Yet with all that deformity was a certain fearsome appearance of vigor, agility, and courage; a strange exception to the eternal rule prescribing that strength, like beauty, shall result from harmony. Such was the pope whom the fools had chosen.

He looked like a giant that had been broken and badly repaired.

When this sort of Cyclops appeared on the threshold of the chapel, motionless, chunky, and almost as broad as he was high, "the square of his base," as one great man puts it, the populace immediately recognized him by his coat, half red and half purple, sprinkled with little silver bells, and especially by the perfection of his ugliness - the populace recognized him, I say, and cried out with one voice:

"It's Quasimodo, the bellringer. It's Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre-Dame! Quasimodo the one-eyed! Quasimodo the bowlegged! Noel! Noel!"

So, while the free Project Gutenberg ebook is quite readable, it is written in 19th century English and Hapgood seemed to be aiming for as literal a translation as she could render. The Cobb translation is a better read, so I recommend it. (I haven't compared any of the other translations, but there are even more recent ones to choose from.)

How many different ways can Hollywood miss the point?

As usual, I Netflixed every available film version to complete my Notre-Dame experience. As usual, some of the film versions were good (my favorites were the two earliest ones) and some were not (*cough*Disney*cough). However, I have never yet read a classic novel with so many different film versions that all completely missed major points of the novel so completely.

I don't think you could do justice to Victor Hugo's novel on film; those long expository blocks of text are too essential to the book and completely inappropriate for a movie, but there are also too many details and too many different ways in which the interwoven fates of numerous characters touch on one another. But let me point out of a few details that not one film version got right:

1. Esmeralda is a sixteen-year-old virgin. (Few film versions depict her as a teenager, and most make her out to be a sexy temptress.) She's kind-hearted, fierce-tempered, but also naive, lovesick, and silly, right at that age where she's willing to throw her life away for a schmuck like Phoebus de Chateaupers. She's such an innocent you can understand Quasimodo's desire to protect her, and she's also so foolish you want to slap her.

2. Quasimodo is not mentally retarded, as he is often depicted in the films. He's deaf and physically deformed and extremely anti-social, but although his voice is off-key from disuse and having gone deaf at a young age, he's able to speak quite fluently when he wants to, and he's far from stupid.

3. Dom Claude Frollo isn't evil and he doesn't abuse Quasimodo, at least not at first. In fact, that's part of the point of the novel: Frollo actually starts out as a kind and moral, if rather severely pious, priest. He took Quasimodo in as a foundling and he takes care of his irresponsible younger brother, to whom he continually gives money even though he knows the brat is just going to spend it on drink, and he's completely dedicated to religion and his studies. It's his infatuation with Esmeralda, after having lived a life hitherto free of any carnal desires, that causes him to come apart and turn into a demonic wretch. No genre fantasy writer has written a better and more richly realized Evil Wizard.

4. Phoebus's name is entirely and deliberately ironic. He's a selfish jerk who just wants to carouse and get laid. In fairness, some film adaptations did get this part right, but the Disney version isn't the only one that makes him out to be a dashing hero. He's actually responsible for most of the bad things that happen, and he never notices or cares.

Those are just character details, though, and not even the biggest aspects of the book that all the films miss. I can't emphasize this enough: there are a lot of books where of course you'll miss things in the film versions, but at least the better ones represent the book well enough that you can say you more or less know the story after watching them. Dickens and Austen, for example, translate pretty well on film. Not true of The Hunchback of Notre Dame; the film versions will give you most of the major plot points, but none have all of them, or connect them the way Hugo did, or represent the characters faithfully. I didn't see a single one that did more than scratch the surface of Victor Hugo's novel.

Read the book. It's a great book, and the movies are all pale approximations.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923)

This silent film made Lon Chaney a star, and set the trend for casting poor, sad Quasimodo as a Hollywood monster with the likes of Frankenstein and Dracula. It's actually quite fun to watch, especially Lon Chaney capering about as Quasimodo in all his impish, malicious glee, climbing over buttresses and gargoyles and ringing the bells of Notre Dame. It can't really convey anything like the true scope of Hugo's novel and it took many liberties with the story, so like every other version, it should be viewed on its own terms as a movie of the era inspired by a book.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

Charles Laughton and Maureen O'Hara starred in the first film adaptation made after the introduction of "talkies." This was a big budget production with large sets, and plays out like any grand Hollywood epic of the era, as a story that can at best be called loosely based on the book. There are all sorts of subplots and deviations having little to do with Victor Hugo's novel, with many invented scenes and conversations. As usual, the character of Dom Frollo and his relationship with his brother are changed the most, but there are other major alterations in terms of who lives and who dies.

For all that it wasn't a very faithful adaptation, though, this was a good movie, and very entertaining. It was actually one of my favorite versions, but it's not one from which to get much sense of the book.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1957)

Eighteen years later, we have the first color film version, starring Anthony Quinn and Gina Lollobrigida. This adaptation was almost the reverse of the 1939 classic: it preserves more of the book in terms of scenes and characters, but is completely unfaithful to its spirit and it's generally kind of a crappy movie that mostly capitalizes on Gina Lollobrigida's sexiness. Anthony Quinn's Quasimodo is just an ugly simpleton, not the self-aware and cunning but monstrously deformed Quasimodo of the book. It's the kind of movie where at least the scriptwriter obviously read the book, but the director obviously didn't.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1982)

This was a 1982 made-for-TV adaptation starring Anthony Hopkins. It was very 80s. I've argued above that Victor Hugo's novel is a fantasy epic without the "fantasy"; this movie greatly resembled the schlocky fantasy movies of the 80s: it's all horsecarts and dungeons and chainmail and sinister robes and bosom-revealing gowns and actors and actresses wearing lots of eyeshadow. It's a colorful, pretty production, but yet again misses the mark by a wide margin, makes little attempt to be faithful to the novel, and to the degree that it did preserve any of Hugo's plot, it dumbed it down substantially for the prime time audience.

Vox Lumiere: The Hunchback of Notre Dame (2007)

I was honestly not sure what this was when I Netflixed it, but hey, I like musicals and it came up when I searched for every available version of "The Hunchback of Notre Dame," so...

This was a bizarre musical production by Vox Lumiere, a sort of rock choral/dance group that mixes rock opera with silent films. Basically you have goths in fishnet stockings and black t-shirts dancing around a stage with the 1923 Lon Chaney silent film playing on a big screen overhead, and singing lyrics like this:

King of darkness

King of shame

King of nowhere

With no one else to blame!

King of nightmares

King of fear

King of screaming

That no one ever hears!

o..O

Yeah, it was weird. Maybe it's cool to see live. On DVD, it looked like one of the more boring episodes of Glee, with worse lighting and more mascara.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Disney, 1996)

So of course to round off my cinematic experience, I had to see the Disney version, which I had never seen previously. Naturally, I wasn't expecting it to resemble the book much, and it didn't. On the other hand, I know this is a pretty low bar, but this was not the worst Disney adaptation I've ever seen. I mean, it actually kept most... okay, some...okay, a few of the characters, who kinda sorta resembled their literary namesakes, and the course of the plot very generally followed Hugo's novel, if you take out all the bad, sad, and tragic parts and add the usual "equality/diversity/justice/friendship is magic" Disney gloss. Okay, so yeah, it didn't really resemble the book at all. Also, the musical numbers were completely unmemorable. Oh well.

Verdict: This book is why you should read classics, and why some books are worth a bit of persistence even if they don't grab you right away. I was expecting it to be a slog to get through Notre-Dame de Paris, and at first it was, but gradually it became more interesting, I began to appreciate both the epic scope of the story Victor Hugo had been building piece by piece, and also the sense of humor he'd been wryly displaying all along. No matter which film version you've seen, you have not gotten anything like the story of "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" unless you've read Victor Hugo's novel in its entirety, and it absolutely deserves to be read, and to be on the list of 1001 books you must read before you die. I liked it so much that I was actually motivated to add Hugo's other big novel, Les Misérables, to my TBR list.

This was my twelfth assignment for the books1001 challenge.

First published (in French) in 1831.

English translation by Isabel F. Hapgood published in 1881. Approx. 185,000 words. Available for free at Project Gutenberg.

Set amid the riot, intrigue, and pageantry of medieval Paris, Victor Hugo's masterful tale of heroism and adventure has been a perennial favorite since its first publication in 1831. It is the story of Quasimodo, the deformed bell-ringer of the Notre Dame Cathedral, who falls in love with the beautiful gypsy Esmeralda. When Esmeralda is condemned as a witch by Claude Frollo, the tormented archdeacon who lusts after her, Quasimodo attempts to save her; but his intentions are misunderstood. Written with a profound sense of tragic irony, Hugo's powerful historical romance remains one of the most thrilling stories of all time.

The proper title of Victor Hugo's novel is Notre-Dame de Paris. Contrary to what every movie based on the book would lead you to believe (see below), it is primarily about Paris and the cathedral and medieval French society, against which backdrop a story of obsessive lust, naive love, and betrayal unfolds. At some point an English translator decided that Quasimodo was the main character, and so forever after Hugo's novel has been translated into English as "The Hunchback of Notre Dame." Most of the film adaptations (starting with the 1923 Lon Chaney one) cast it as a gothic horror piece, thus associating the "hunchback" reference even more strongly with the novel. But Lon Chaney and Disney cartoons notwithstanding, this story is as much about the city of Paris and Our Lady of Paris as it as about a hunchback and a gypsy dancer.

Written almost 200 years ago, Notre-Dame de Paris is set in 1482. Victor Hugo was writing a historical novel set 350 years before his time. He was obviously fascinated by the history and architecture of medieval Paris (as is alluded to in the foreword), and boy does he want to tell you about it.

The novel begins with the Epiphany and the Feast of Fools in January, 1482. Among the events being held that day in the city of Paris is a Mystery play at the Palais de Justice. Parisians flock to the Palais to be entertained, and here we see our first glimpse of the classes mingling: academicians, bourgeois, clergy, and beggars all throng about in the Palais clamoring for the play to begin. They soon become quite rowdy, and the scene proceeds in a slow but humorous fashion, spanning several chapters. The first main character to whom we are introduced is Pierre Gringoire, a hapless, penniless playwrite. He's waiting for the Archdeacon to show up to see his masterpiece and become his patron. The restless crowd threatens to lynch Gringoire and his cast if they don't start immediately, and everything degenerates into chaos and comedy.

The humor sneaks up on you, as it does throughout the book. Poor Gringoire is alternately trying to flirt with pretty girls, elicit praise for his play, get the crowd's attention, and keep from being lynched. The description of the play he's trying to put on is hilarious-he has grand artistic pretensions and he wrote this absurd monstrosity, rich with classical allusions and sucking up to current political figures, and he presents it to a mob that just wants to be entertained, and will be as entertained by hanging the actors as by watching them perform.

Quasimodo doesn't show up until Chapter 5, when he wins a "grimacing contest" and is elected as the Pope of Fools:

Or rather, his whole person was a grimace. A huge head, bristling with red hair; between his shoulders an enormous hump, a counterpart perceptible in front; a system of thighs and legs so strangely astray that they could touch each other only at the knees, and, viewed from the front, resembled the crescents of two scythes joined by the handles; large feet, monstrous hands; and, with all this deformity, an indescribable and redoubtable air of vigor, agility, and courage,--strange exception to the eternal rule which wills that force as well as beauty shall be the result of harmony. Such was the pope whom the fools had just chosen for themselves.

One would have pronounced him a giant who had been broken and badly put together again.

When this species of cyclops appeared on the threshold of the chapel, motionless, squat, and almost as broad as he was tall; squared on the base, as a great man says; with his doublet half red, half violet, sown with silver bells, and, above all, in the perfection of his ugliness, the populace recognized him on the instant, and shouted with one voice,--

"'Tis Quasimodo, the bellringer! 'tis Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre-Dame! Quasimodo, the one-eyed! Quasimodo, the bandy-legged! Noel! Noel!"

While Quasimodo is being carried through the streets by the raucous crowd, Gringoire is looking for a place to sleep, now that his play has been ruined and he hasn't been paid. Stumbling through the streets, he witnesses the beautiful gypsy dancer Esmeralda, who is subsequently almost abducted by Quasimodo before being rescued by a handsome captain of the guard named Phoebus.

Gringoire ends up taking a wrong turn and finds himself in the bad part of town, confronted by the King of Vagabonds and the Thieves' Court, where he is sentenced to be hanged. He's saved at the last minute by the sudden appearance of Esmeralda, who agrees to "marry" him in order to spare him from being hanged.

Gringoire, is easily the most amusing character in the book. He gets an awful lot of chapters even though his impact on the story is minimal. He loses no time getting over his homelessness and near-death experience as soon as he thinks he's going to score.

The gypsy's corsage slipped through his hands like the skin of an eel. She bounded from one end of the tiny room to the other, stooped down, and raised herself again, with a little poniard in her hand, before Gringoire had even had time to see whence the poniard came; proud and angry, with swelling lips and inflated nostrils, her cheeks as red as an api apple, and her eyes darting lightnings. At the same time, the white goat placed itself in front of her, and presented to Gringoire a hostile front, bristling with two pretty horns, gilded and very sharp. All this took place in the twinkling of an eye.

The dragon-fly had turned into a wasp, and asked nothing better than to sting.

Our philosopher was speechless, and turned his astonished eyes from the goat to the young girl. "Holy Virgin!" he said at last, when surprise permitted him to speak, "here are two hearty dames!"

The gypsy broke the silence on her side.

"You must be a very bold knave!"

"Pardon, mademoiselle," said Gringoire, with a smile. "But why did you take me for your husband?"

"Should I have allowed you to be hanged?"

"So," said the poet, somewhat disappointed in his amorous hopes. "You had no other idea in marrying me than to save me from the gibbet?"

"And what other idea did you suppose that I had?"

At this point, Hugo has now introduced all the main characters and established the plot elements that will drive the rest of the story, although much of what is actually going on is not yet apparent to the reader. Here I was forming a favorable impression of the book, as I love an author who's got a knack for putting everything together nicely, and I'm okay with taking your time to develop the story if it's engaging along the way.

And right here is where Hugo decides to walk away from the story for a while to deliver some huge infodumps.

My research, let me show you it

In Part Three, the author stops the story entirely to spend a couple of chapters telling us all about Paris and Notre-Dame. Victor Hugo researched the history of Paris and how it grew from a little island settlement on the Seine to expand across the Left and Right Banks, and how all the neighborhoods, fortifications, walls, buildings, and architectural styles that grew up in successive layers came to be, as well as the medieval division between Town, City, and University.

Needless to say, this is something few modern writers could get away with. Contemporary readers are not fond of infodumps like this, especially when they completely interrupt the flow of the story. I am not fond of infodumps like this; it was a chore to plow through 50 pages about every wall and gate and bridge in Paris.

However, if you are a writer who has an interest in writing medieval fantasy, I don't think you could do better than read Notre-Dame de Paris to get a great big dose of verisimilitude about what medieval cities actually looked like. Hugo carefully strips away the layers of Paris from its earliest foundations to the city as it was at the time about which he is writing, and then comments on the city as it was at the time he was writing (the 19th century), with many lamentations about the poor job modern architects were doing in preserving the old facades and stonework.

The Paris of the present day has then, no general physiognomy. It is a collection of specimens of many centuries, and the finest have disappeared. The capital grows only in houses, and what houses! At the rate at which Paris is now proceeding, it will renew itself every fifty years.

Thus the historical significance of its architecture is being effaced every day. Monuments are becoming rarer and rarer, and one seems to see them gradually engulfed, by the flood of houses. Our fathers had a Paris of stone; our sons will have one of plaster.

Indeed, you can see Hugo's medieval Paris echoed in many fantasy novels. When I read about the University, the Town, and the City, I immediately thought of Patrick Rothfuss's The Name of the Wind; if Rothfuss did not read Notre-Dame de Paris himself, he was certainly influenced by other historical and fantasy writers who had. Likewise, the Kingdom of Argotiers is the model for every "Thieves Guild" written since.

Notre-Dame de Paris is Epic

So after being thrown out of the story a bit by the long exposition, it took me a while to get back into the story, but once I did, I began to fall under its spell. Notre-Dame de Paris is one of those books that requires patience: it is rewarding only after you've read hundreds of pages of set-up. If that sounds like too much to ask from a modern reader, then it's a shame, but I'm glad I did stick with it because this was one of my "assigned" books from the books1001 challenge. Most people (who have not read the book) think "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" is about the mistreated outcast Quasimodo rescuing Esmeralda from the evil Claude Frollo. But those are really only part of a long chain of events that invoke irony, tragedy, humor and pathos, connecting beggars on the streets of Paris to Louis XI. In this chain reaction leading to its dramatic climax, Quasimodo and Esmeralda are only catalysts. The two of them are significant characters, but they are not really "main" characters any more than Pierre Gringoire and Claude Frollo and Captain Phoebus, all of whom get about as much page space, and towering over all of them, present on nearly every page, is Notre-Dame de Paris, the true main character.

Notre-Dame de Paris is a fantasy novel

Seriously. This is a medieval fantasy novel, it just doesn't have any literal magic or literally supernatural creatures. You've got a medieval city described in great detail. The main characters include thieves, clerics, knights, and bards, a monstrous hero with superhuman strength, and a beautiful damsel in distress with an animal companion. The action takes place in cathedrals, back alleys, palaces, inns, and dungeons. There are assassins and brigands and nobles, and while Claude Frollo, who is called a sorcerer by the townspeople, may not actually cast spells, he studies alchemy and hermeticism and astrology, and the description of his laboratory and his books is as complete a description of a wizard's tower as any fantasy novelist has written. There's romance and political intrigue, pitched battles between peasant footsoldiers and cavalry and archers, escapes through secret passages, and a siege repelled by a monster with rocks and molten lead.

If you don't demand elves and dragons, this book isn't missing anything else to be classified as a fantasy epic.

It's also funnier than you think

It took me a while to realize this. Victor Hugo is being funny. You can talk about your dry British humor, but Hugo's wit is as arid as it is acid. Notre Dame de Paris is full of jokes which are reminiscent of Jane Smiley's observation about French novelists in Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel, that whereas English novelists often presented an idealized version of England, French novelists tended to portray France as a vipers' nest.

In every chapter from the misadventures of Pierre Gringoire to the most benevolent sagacity of his Majesty Louis XI, Hugo inserts some wry aside. And his habit of writing long blocks of expository text reveals itself as his way of taking his time in setting up a punchline.

"Master Olivier, princes who reign over great siegneuries, as kings and emperors, ought not to allow extravagance to creep into their households, for 'tis a fire that will spread thence into the provinces....

(Louis XI goes on ranting for several paragraphs about increasing expenses.)

He stopped, out of breath, then resumed with vehemence.

"I see all around me nothing but people who are getting fat on my leanness. You are sucking money from my every pore!"

Everyone remained silent. It was one of his fits of passion which had to run its course.

This section goes on for a couple of pages with Louis XI's comptroller itemizing all his expenses and the king complaining about everything from the cost of clothes to the number of chefs on his staff.

Then:

"Divers partitions, planks, and trapdoors, for the safe-keeping of lions at the Hotel Saint-Paul, twenty-two livres."

"They are costly beasts!" said Louis XI. "But no matter; it's a fair piece of royal magnificence. There is a great red lion which I am very fond of for his engaging ways. Have you seen him, Master Guillaume? Princes should have those remarkable animals. We kings ought to have lions for our dogs and tigers for our cats. The great beasts befit a crown. In the time of the pagans of Jupiter, when the people offered up at the holy places a hundred oxen and a hundred sheep, the emperor gave a hundred lions and a hundred eagles. That was very fierce and noble. The kings of France have always had those roarings about their throne. Nevertheless, people must do me the justice to say that I spend less money in that way than my predecessors, and that I am exceedingly moderate on the score of lions, bears, elephants, and leopards."

The right translation

Notre-Dame De Paris has been translated into English many times. I had not previously given much thought to hunting around for the best version of a novel with multiple translations.

I started reading the Project Gutenberg version, because it was free. This was the 1888 Isabel Hapgood translation. However, thanks to my ereader needing to be replaced, I was less than halfway through when I checked out a paperback from the library to finish it. This turned out to be the 1964 Walter J. Cobb translation.

This translation was much better. The English was more contemporary, the translation idiomatic but smooth, and suddenly reading this book was a much more pleasant experience. It's very close to the Hapgood translation, but compare this passage to the Hapgood translation of the same passage above:

Rather his whole person was a grimace. His enormous head bristled with red hair; between his shoulders was an enormous hump, counterbalanced by a protuberance in front; he had a framework of thighs and legs so strangely askew that they could touch only at the knees, and, seen from the front, resembled two sickles joined together at the handles. The feet were huge; the hands monstrous. Yet with all that deformity was a certain fearsome appearance of vigor, agility, and courage; a strange exception to the eternal rule prescribing that strength, like beauty, shall result from harmony. Such was the pope whom the fools had chosen.

He looked like a giant that had been broken and badly repaired.

When this sort of Cyclops appeared on the threshold of the chapel, motionless, chunky, and almost as broad as he was high, "the square of his base," as one great man puts it, the populace immediately recognized him by his coat, half red and half purple, sprinkled with little silver bells, and especially by the perfection of his ugliness - the populace recognized him, I say, and cried out with one voice:

"It's Quasimodo, the bellringer. It's Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre-Dame! Quasimodo the one-eyed! Quasimodo the bowlegged! Noel! Noel!"

So, while the free Project Gutenberg ebook is quite readable, it is written in 19th century English and Hapgood seemed to be aiming for as literal a translation as she could render. The Cobb translation is a better read, so I recommend it. (I haven't compared any of the other translations, but there are even more recent ones to choose from.)

How many different ways can Hollywood miss the point?

As usual, I Netflixed every available film version to complete my Notre-Dame experience. As usual, some of the film versions were good (my favorites were the two earliest ones) and some were not (*cough*Disney*cough). However, I have never yet read a classic novel with so many different film versions that all completely missed major points of the novel so completely.

I don't think you could do justice to Victor Hugo's novel on film; those long expository blocks of text are too essential to the book and completely inappropriate for a movie, but there are also too many details and too many different ways in which the interwoven fates of numerous characters touch on one another. But let me point out of a few details that not one film version got right:

1. Esmeralda is a sixteen-year-old virgin. (Few film versions depict her as a teenager, and most make her out to be a sexy temptress.) She's kind-hearted, fierce-tempered, but also naive, lovesick, and silly, right at that age where she's willing to throw her life away for a schmuck like Phoebus de Chateaupers. She's such an innocent you can understand Quasimodo's desire to protect her, and she's also so foolish you want to slap her.

2. Quasimodo is not mentally retarded, as he is often depicted in the films. He's deaf and physically deformed and extremely anti-social, but although his voice is off-key from disuse and having gone deaf at a young age, he's able to speak quite fluently when he wants to, and he's far from stupid.

3. Dom Claude Frollo isn't evil and he doesn't abuse Quasimodo, at least not at first. In fact, that's part of the point of the novel: Frollo actually starts out as a kind and moral, if rather severely pious, priest. He took Quasimodo in as a foundling and he takes care of his irresponsible younger brother, to whom he continually gives money even though he knows the brat is just going to spend it on drink, and he's completely dedicated to religion and his studies. It's his infatuation with Esmeralda, after having lived a life hitherto free of any carnal desires, that causes him to come apart and turn into a demonic wretch. No genre fantasy writer has written a better and more richly realized Evil Wizard.

4. Phoebus's name is entirely and deliberately ironic. He's a selfish jerk who just wants to carouse and get laid. In fairness, some film adaptations did get this part right, but the Disney version isn't the only one that makes him out to be a dashing hero. He's actually responsible for most of the bad things that happen, and he never notices or cares.

Those are just character details, though, and not even the biggest aspects of the book that all the films miss. I can't emphasize this enough: there are a lot of books where of course you'll miss things in the film versions, but at least the better ones represent the book well enough that you can say you more or less know the story after watching them. Dickens and Austen, for example, translate pretty well on film. Not true of The Hunchback of Notre Dame; the film versions will give you most of the major plot points, but none have all of them, or connect them the way Hugo did, or represent the characters faithfully. I didn't see a single one that did more than scratch the surface of Victor Hugo's novel.

Read the book. It's a great book, and the movies are all pale approximations.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923)

This silent film made Lon Chaney a star, and set the trend for casting poor, sad Quasimodo as a Hollywood monster with the likes of Frankenstein and Dracula. It's actually quite fun to watch, especially Lon Chaney capering about as Quasimodo in all his impish, malicious glee, climbing over buttresses and gargoyles and ringing the bells of Notre Dame. It can't really convey anything like the true scope of Hugo's novel and it took many liberties with the story, so like every other version, it should be viewed on its own terms as a movie of the era inspired by a book.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939)

Charles Laughton and Maureen O'Hara starred in the first film adaptation made after the introduction of "talkies." This was a big budget production with large sets, and plays out like any grand Hollywood epic of the era, as a story that can at best be called loosely based on the book. There are all sorts of subplots and deviations having little to do with Victor Hugo's novel, with many invented scenes and conversations. As usual, the character of Dom Frollo and his relationship with his brother are changed the most, but there are other major alterations in terms of who lives and who dies.

For all that it wasn't a very faithful adaptation, though, this was a good movie, and very entertaining. It was actually one of my favorite versions, but it's not one from which to get much sense of the book.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1957)

Eighteen years later, we have the first color film version, starring Anthony Quinn and Gina Lollobrigida. This adaptation was almost the reverse of the 1939 classic: it preserves more of the book in terms of scenes and characters, but is completely unfaithful to its spirit and it's generally kind of a crappy movie that mostly capitalizes on Gina Lollobrigida's sexiness. Anthony Quinn's Quasimodo is just an ugly simpleton, not the self-aware and cunning but monstrously deformed Quasimodo of the book. It's the kind of movie where at least the scriptwriter obviously read the book, but the director obviously didn't.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1982)

This was a 1982 made-for-TV adaptation starring Anthony Hopkins. It was very 80s. I've argued above that Victor Hugo's novel is a fantasy epic without the "fantasy"; this movie greatly resembled the schlocky fantasy movies of the 80s: it's all horsecarts and dungeons and chainmail and sinister robes and bosom-revealing gowns and actors and actresses wearing lots of eyeshadow. It's a colorful, pretty production, but yet again misses the mark by a wide margin, makes little attempt to be faithful to the novel, and to the degree that it did preserve any of Hugo's plot, it dumbed it down substantially for the prime time audience.

Vox Lumiere: The Hunchback of Notre Dame (2007)

I was honestly not sure what this was when I Netflixed it, but hey, I like musicals and it came up when I searched for every available version of "The Hunchback of Notre Dame," so...

This was a bizarre musical production by Vox Lumiere, a sort of rock choral/dance group that mixes rock opera with silent films. Basically you have goths in fishnet stockings and black t-shirts dancing around a stage with the 1923 Lon Chaney silent film playing on a big screen overhead, and singing lyrics like this:

King of darkness

King of shame

King of nowhere

With no one else to blame!

King of nightmares

King of fear

King of screaming

That no one ever hears!

o..O

Yeah, it was weird. Maybe it's cool to see live. On DVD, it looked like one of the more boring episodes of Glee, with worse lighting and more mascara.

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (Disney, 1996)

So of course to round off my cinematic experience, I had to see the Disney version, which I had never seen previously. Naturally, I wasn't expecting it to resemble the book much, and it didn't. On the other hand, I know this is a pretty low bar, but this was not the worst Disney adaptation I've ever seen. I mean, it actually kept most... okay, some...okay, a few of the characters, who kinda sorta resembled their literary namesakes, and the course of the plot very generally followed Hugo's novel, if you take out all the bad, sad, and tragic parts and add the usual "equality/diversity/justice/friendship is magic" Disney gloss. Okay, so yeah, it didn't really resemble the book at all. Also, the musical numbers were completely unmemorable. Oh well.

Verdict: This book is why you should read classics, and why some books are worth a bit of persistence even if they don't grab you right away. I was expecting it to be a slog to get through Notre-Dame de Paris, and at first it was, but gradually it became more interesting, I began to appreciate both the epic scope of the story Victor Hugo had been building piece by piece, and also the sense of humor he'd been wryly displaying all along. No matter which film version you've seen, you have not gotten anything like the story of "The Hunchback of Notre Dame" unless you've read Victor Hugo's novel in its entirety, and it absolutely deserves to be read, and to be on the list of 1001 books you must read before you die. I liked it so much that I was actually motivated to add Hugo's other big novel, Les Misérables, to my TBR list.

This was my twelfth assignment for the books1001 challenge.