My theory, which is mine

Several things recently have made me think about the use of history in the Buffyverse. First, when I was looking for articles on filmed versions of Jane Austen in a book called Jane Austen and Co., I encountered an article called Love on the Hellmouth by Kristina Straub, which explored the importance of the past, of history and of teaching in all its forms in BtVS. No, I’m not quite sure why, either.

ETA: 2018. The curse of Photobucket struck this very severely. I have replaced enough of the photos for it, I hope, to make sense, but I've deleted those I couldn't replace. The V&A site is full of useful references if you Google 1880 costume, though.

Then shapinglight posted about Lies My Parents Told Me and the reasons for her dislike of the episode. There was a long and interesting discussion following that, well worth reading.

During this I, and a couple of others, mentioned my long-standing theory about the only plausible explanation of the events which led to William’s vamping.

Of course, on a Doylist level, I know very well that time was short; ME was attempting a tricky double crossover of linked episodes, after all. History, at least nineteenth century British history, probably wasn’t the major of any of the ME writers, the costuming of characters with two sentences in a single flashback scene was not a high priority, and the budget wasn’t inexhaustible. James Marsters’ accent wasn’t bad, but it slipped a couple of times, as did Kali Rocha’s, and all that was asked of the walk-ons was in essence caricature.

However, I want to look at this from an in-universe, aka Watsonian perspective. If what we saw was what happened, then what did we see happening? How can all the visual evidence be integrated into the storyline to make maximum sense?

Here the author’s intentions are not relevant. Doug Petrie, in his commentary, makes his view of the social event clear: to him it is a high society event in which William is bullied and his insecurities are reinforced. That is not, however, what we were shown.

(Captioned photo copied from Shangel's blog.)

There are two major areas which are problematic for anyone with much knowledge of the 1880s - what we see and what we hear. That’s all. *g* I’ll start with what we see.

We are in a room with heavy curtains, upholstered furniture intended to seat groups, an open staircase leading out of the single, large room where the company is being entertained. It is evening, as we are reminded later, when William runs out into the night in tears.

Victorian domestic settings in London were not arranged that way, as anyone who has been in many can confirm. This was the period of the cult of Home and Hearth and a rigid separation, physical as well as psychological, of indoors and outdoor spaces - there was usually a double entry, so that callers had somewhere dry to wait for admission, a tiled hallway, getting wider as houses go upmarket, and a staircase leading to the inner sanctum of the house. (Early Victorian houses and many later ones in areas like Mayfair where space was at a premium actually had reception rooms up one flight of stairs, but the same applied about a separate hall and stairway.)

This, then, looks like a semi-public space. There is no visible bar or doors to a performance space, so it is presumably not a “place of public entertainment” as licensing laws introduced only a few years later would call it. Thus it is either a private club - gaming, for example, but definitely not a gentleman’s club - or a house of ill-repute.

Turning to the other important element of the setting, the attire of the “guests”. While all the signs are that it is an evening function, none of the men are wearing correct evening clothes. Indeed, they are not even wearing correct day wear for gentlemen in the London of 1880.

During the working week respectable men mostly wore dark colours, predominantly black, though lighter colours were often fashionable for leisure clothing. The majority of the men in the scene are wearing brown, including William, and many of them are in relatively pale colours. They are almost all wearing ties or cravats tied in the extra-large knot, twice the size of what is today known as a “Windsor”, and not at the time really considered appropriate for genteel wear in Town. One of the more hurtful individuals is wearing a tie with a huge knot in fabric which looks identical in colour and pattern to the overdress of his female companion. (See first picture.)

This deserves a line to itself - real gentlemen of the period would have been in evening dress if the function they were attending was “respectable”.

Now for the ladies. Cecily is in evening wear - a very décolleté dress without sleeves. The amount of floristry on the pleated decoration of the neckline is perhaps a little excessive, and the gown is perhaps a little more suited to a married lady than the umarried girl she is presented as. Compare this fashion plate of the period:

with Cecily's gown as she sits with William (above.)

The way in which she walks down the stairs rather implies she is well-known to the assembled company and at home in that setting, but this is not in itself evidence against her.

It is when we turn to the other females present that we encounter a problem. Most of them are wearing day wear, at least one in what appears to be a printed cotton of the sort considered in London to be more appropriate to the servant or possibly artisan class.

This is a day dress from the V&A collection.

Their hair is much less elaborately decorated than Cecily’s, and they seem to be socially subordinate. One woman, however, stands out even from them - it is, tellingly, the woman who makes the unkind remark about William and his poetry. Her dress, insofar as it represents any fashion at all, is about 40-50 years earlier. Her hair-style, too, is almost exactly like what we see in contemporary illustrations of early Dickens characters. She has a low, green, frilled “shift” under a shiny brown and gold striped overdress - the fabric appearing to match the cravat of the man who declaims William’s poem. There is no possible way she could be taken as a lady of quality. (See above.)

Compare this:

Then we come to what we hear: the accents and vocabulary. The woman described above has an extremely artificial upper-class accent - too careful, one might suggest. Cecily, however, has a somewhat more hybrid accent, with several “a” sounds more common in the North (as in “cat”) than London society. Interestingly, William, too, very occasionally uses these sounds (as, over a century later, he will refer to “me mum” in a very Northern voice.) It was far from unusual at that period for people to attempt to hide their provincial origins on arriving in London - the fact that William suspects Drusilla of being “one of your London pickpockets” might be taken to reinforce this possibility. It would certainly help to account for his innocence and naivety in this setting.

The vocabulary, however, is even more telling. The oddly-dressed woman refers to his poetry as “bloody awful”. Over thirty years later the word “bloody” was still so taboo that a single use in Pygmalion was considered deeply shocking. Her companion talks about his preference for being beaten to death with a “railroad spike”, an article of ironmongery which did not exist in Britain at that time - nor, for that matter, did a “railroad”. This couple are not quite what they seem - and they seem pretty dodgy to me in any case.

There are two possible interpretations. There is evidence that “Cecily” is, in fact, a demon called Halfrek - perhaps this couple are also of the demon persuasion, which would explain their gratuitous cruelty to our poet. Alternatively - and all the signs and signifiers might well support this - we are in a rather exclusive brothel.

Paris of the period was infamous for the “demi-monde” - the half-world of courtesans, their lovers and the infrastructure of couturiers, pimps, servants and places of entertainment needed to sustain them. London was superficially more restrained, but prostitution was very common indeed, through all levels of society. One of the most famous of the Parisian “grandes horizontales”, Cora Pearl, was born an Englishwoman, Emma Elizabeth Crouch. Throughout William’s lifetime, the London world of “fair frailty” was dominated by celebrity courtesans such as “Skittles”, who was worth nearly three thousand pounds when she died.

William, naïve, inexperienced, possibly a stranger to London, would have been quite unable to read the signs. The fact that Cecily appears to have two surnames also seems suspicious. The cruelty of the blasé group of roués and loose women is easily explicable if that is indeed their real identity. The atmosphere is certainly arousing - when William consents to Drusilla it is surely to sex, rather than a painful and bloody death that he agrees. And the look on his face as he falls suggests he is not entirely a stranger to ecstasy in his final moments of life.

Was William a virgin? Probably. Did he understand the sort of place he was in? Possibly. If not, he was immune to all the signals just as, a few minutes later, he was immune to the signals of danger from Drusilla. If he did, perhaps his poetry was his way of nerving himself up to approaching a woman way too expensive for him - and in that way alone, he was beneath her.

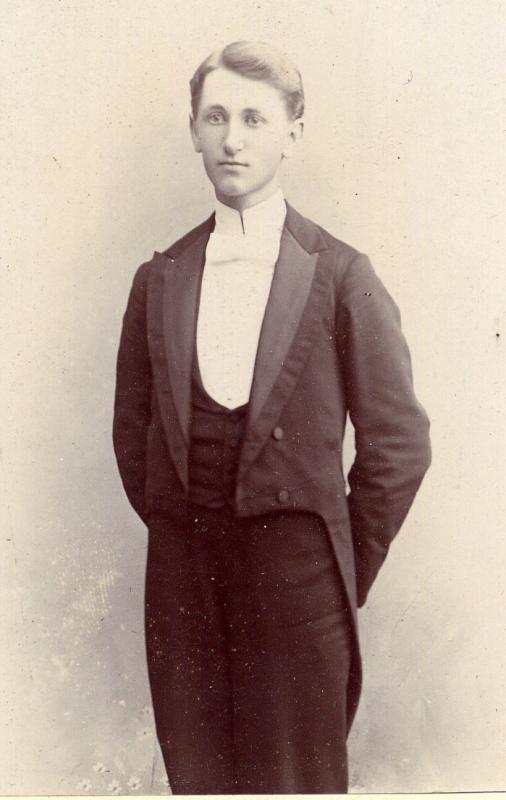

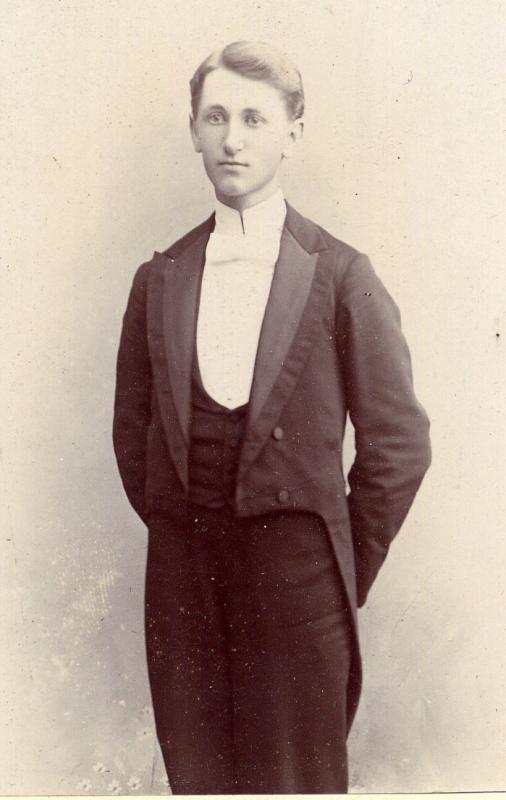

ETA: A description of male evening dress:

Image"When a gentleman is invited out for the evening, he is under no embarrassment as to what he shall wear. He has not to sit down and consider whether he shall wear blue or pink, or whether the Joneses will notice if he wear the same attire three times running. Fashion has ordained for him that he shall always be attired in a black dress suit in the evening, only allowing him a white waistcoat as an occasional relief to his toilette. His necktie must be white or light colored. An excess of jewelry is to be avoided but he may wear gold or diamond studs, and a watch chain. He may also wear a flower in his buttonhole, for this is one of the few allowable devices by which he may brighten his attire.

Plain and simple as the dress is, it is a sure test of a gentlemanly appearance. The man who dines in evening dress every night of his life looks easy and natural in it, whereas the man who takes to it late in life generally succeeds in looking like a waiter."

The Ball Room Guide. 1860

ETA: 2018. The curse of Photobucket struck this very severely. I have replaced enough of the photos for it, I hope, to make sense, but I've deleted those I couldn't replace. The V&A site is full of useful references if you Google 1880 costume, though.

Then shapinglight posted about Lies My Parents Told Me and the reasons for her dislike of the episode. There was a long and interesting discussion following that, well worth reading.

During this I, and a couple of others, mentioned my long-standing theory about the only plausible explanation of the events which led to William’s vamping.

Of course, on a Doylist level, I know very well that time was short; ME was attempting a tricky double crossover of linked episodes, after all. History, at least nineteenth century British history, probably wasn’t the major of any of the ME writers, the costuming of characters with two sentences in a single flashback scene was not a high priority, and the budget wasn’t inexhaustible. James Marsters’ accent wasn’t bad, but it slipped a couple of times, as did Kali Rocha’s, and all that was asked of the walk-ons was in essence caricature.

However, I want to look at this from an in-universe, aka Watsonian perspective. If what we saw was what happened, then what did we see happening? How can all the visual evidence be integrated into the storyline to make maximum sense?

Here the author’s intentions are not relevant. Doug Petrie, in his commentary, makes his view of the social event clear: to him it is a high society event in which William is bullied and his insecurities are reinforced. That is not, however, what we were shown.

(Captioned photo copied from Shangel's blog.)

There are two major areas which are problematic for anyone with much knowledge of the 1880s - what we see and what we hear. That’s all. *g* I’ll start with what we see.

We are in a room with heavy curtains, upholstered furniture intended to seat groups, an open staircase leading out of the single, large room where the company is being entertained. It is evening, as we are reminded later, when William runs out into the night in tears.

Victorian domestic settings in London were not arranged that way, as anyone who has been in many can confirm. This was the period of the cult of Home and Hearth and a rigid separation, physical as well as psychological, of indoors and outdoor spaces - there was usually a double entry, so that callers had somewhere dry to wait for admission, a tiled hallway, getting wider as houses go upmarket, and a staircase leading to the inner sanctum of the house. (Early Victorian houses and many later ones in areas like Mayfair where space was at a premium actually had reception rooms up one flight of stairs, but the same applied about a separate hall and stairway.)

This, then, looks like a semi-public space. There is no visible bar or doors to a performance space, so it is presumably not a “place of public entertainment” as licensing laws introduced only a few years later would call it. Thus it is either a private club - gaming, for example, but definitely not a gentleman’s club - or a house of ill-repute.

Turning to the other important element of the setting, the attire of the “guests”. While all the signs are that it is an evening function, none of the men are wearing correct evening clothes. Indeed, they are not even wearing correct day wear for gentlemen in the London of 1880.

During the working week respectable men mostly wore dark colours, predominantly black, though lighter colours were often fashionable for leisure clothing. The majority of the men in the scene are wearing brown, including William, and many of them are in relatively pale colours. They are almost all wearing ties or cravats tied in the extra-large knot, twice the size of what is today known as a “Windsor”, and not at the time really considered appropriate for genteel wear in Town. One of the more hurtful individuals is wearing a tie with a huge knot in fabric which looks identical in colour and pattern to the overdress of his female companion. (See first picture.)

This deserves a line to itself - real gentlemen of the period would have been in evening dress if the function they were attending was “respectable”.

Now for the ladies. Cecily is in evening wear - a very décolleté dress without sleeves. The amount of floristry on the pleated decoration of the neckline is perhaps a little excessive, and the gown is perhaps a little more suited to a married lady than the umarried girl she is presented as. Compare this fashion plate of the period:

with Cecily's gown as she sits with William (above.)

The way in which she walks down the stairs rather implies she is well-known to the assembled company and at home in that setting, but this is not in itself evidence against her.

It is when we turn to the other females present that we encounter a problem. Most of them are wearing day wear, at least one in what appears to be a printed cotton of the sort considered in London to be more appropriate to the servant or possibly artisan class.

This is a day dress from the V&A collection.

Their hair is much less elaborately decorated than Cecily’s, and they seem to be socially subordinate. One woman, however, stands out even from them - it is, tellingly, the woman who makes the unkind remark about William and his poetry. Her dress, insofar as it represents any fashion at all, is about 40-50 years earlier. Her hair-style, too, is almost exactly like what we see in contemporary illustrations of early Dickens characters. She has a low, green, frilled “shift” under a shiny brown and gold striped overdress - the fabric appearing to match the cravat of the man who declaims William’s poem. There is no possible way she could be taken as a lady of quality. (See above.)

Compare this:

Then we come to what we hear: the accents and vocabulary. The woman described above has an extremely artificial upper-class accent - too careful, one might suggest. Cecily, however, has a somewhat more hybrid accent, with several “a” sounds more common in the North (as in “cat”) than London society. Interestingly, William, too, very occasionally uses these sounds (as, over a century later, he will refer to “me mum” in a very Northern voice.) It was far from unusual at that period for people to attempt to hide their provincial origins on arriving in London - the fact that William suspects Drusilla of being “one of your London pickpockets” might be taken to reinforce this possibility. It would certainly help to account for his innocence and naivety in this setting.

The vocabulary, however, is even more telling. The oddly-dressed woman refers to his poetry as “bloody awful”. Over thirty years later the word “bloody” was still so taboo that a single use in Pygmalion was considered deeply shocking. Her companion talks about his preference for being beaten to death with a “railroad spike”, an article of ironmongery which did not exist in Britain at that time - nor, for that matter, did a “railroad”. This couple are not quite what they seem - and they seem pretty dodgy to me in any case.

There are two possible interpretations. There is evidence that “Cecily” is, in fact, a demon called Halfrek - perhaps this couple are also of the demon persuasion, which would explain their gratuitous cruelty to our poet. Alternatively - and all the signs and signifiers might well support this - we are in a rather exclusive brothel.

Paris of the period was infamous for the “demi-monde” - the half-world of courtesans, their lovers and the infrastructure of couturiers, pimps, servants and places of entertainment needed to sustain them. London was superficially more restrained, but prostitution was very common indeed, through all levels of society. One of the most famous of the Parisian “grandes horizontales”, Cora Pearl, was born an Englishwoman, Emma Elizabeth Crouch. Throughout William’s lifetime, the London world of “fair frailty” was dominated by celebrity courtesans such as “Skittles”, who was worth nearly three thousand pounds when she died.

William, naïve, inexperienced, possibly a stranger to London, would have been quite unable to read the signs. The fact that Cecily appears to have two surnames also seems suspicious. The cruelty of the blasé group of roués and loose women is easily explicable if that is indeed their real identity. The atmosphere is certainly arousing - when William consents to Drusilla it is surely to sex, rather than a painful and bloody death that he agrees. And the look on his face as he falls suggests he is not entirely a stranger to ecstasy in his final moments of life.

Was William a virgin? Probably. Did he understand the sort of place he was in? Possibly. If not, he was immune to all the signals just as, a few minutes later, he was immune to the signals of danger from Drusilla. If he did, perhaps his poetry was his way of nerving himself up to approaching a woman way too expensive for him - and in that way alone, he was beneath her.

ETA: A description of male evening dress:

Image"When a gentleman is invited out for the evening, he is under no embarrassment as to what he shall wear. He has not to sit down and consider whether he shall wear blue or pink, or whether the Joneses will notice if he wear the same attire three times running. Fashion has ordained for him that he shall always be attired in a black dress suit in the evening, only allowing him a white waistcoat as an occasional relief to his toilette. His necktie must be white or light colored. An excess of jewelry is to be avoided but he may wear gold or diamond studs, and a watch chain. He may also wear a flower in his buttonhole, for this is one of the few allowable devices by which he may brighten his attire.

Plain and simple as the dress is, it is a sure test of a gentlemanly appearance. The man who dines in evening dress every night of his life looks easy and natural in it, whereas the man who takes to it late in life generally succeeds in looking like a waiter."

The Ball Room Guide. 1860