"Baker Street 19: A Conversation by a Dwindling Fire"

Watson learns some new things about his intimate friend.

Title: "A Conversation by a Dwindling Fire"

Author: Gaedhal

Pairing/Characters: Sherlock Holmes/Dr. John H. Watson; Mrs. Murray.

Rating: R

Spoilers: None

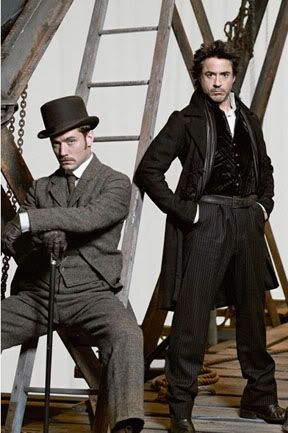

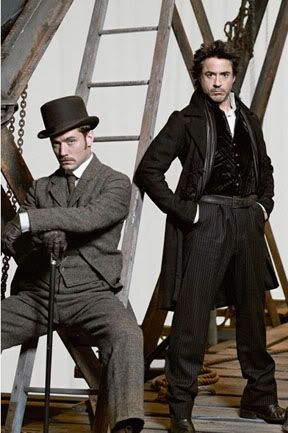

Notes/Warnings: "Sherlock Holmes" (2009) Universe. Set before the Blackwood case.

Disclaimer: This is for fun, not profit. Enjoy.

Summary: Conversation is broadening.

First chapter here:

1. "A Walk to Regent's Park"

http://gaedhal.livejournal.com/367955.html

Previous chapter here:

18. "An Interview with a Young Client"

http://gaedhal.livejournal.com/376625.html

New Chapter here:

By Gaedhal

"A sorry business," I mused, as Holmes and I sat in the library that evening. It was filthy weather outside, with the rain coming down in torrents, and the chill that infested the old house had caused us to draw close to the hearth in search of warmth.

"Men who prey on the weaknesses of their fellows are a sorry lot," Holmes concurred. "Young Griffith is a mere lad, unused to the true evils of the world, and so he was ripe to be exploited. Unfortunately, Major Griffith is an obstinate ass and unlikely to give his son the kind of guidance he will need to avoid such contretemps in the future."

"Charles is a tender-hearted boy," I commented. "He seemed more concerned with the fate of his little paramour than he was with his own future."

"The boy is a fool," Holmes said dismissively. "He imagines he's in love and so is willing to sacrifice all -- his fortune, his good name, even his life. Such poppycock!"

"Perhaps he is in love," I said, watching the last log split and send a shower of sparks up the flue. "The object may seem to us unworthy, but who can peer into a boy's soul? Or a man's?"

"Love!" Holmes almost spat out the word. "Romantic drivel! Thank heaven you and I are men of rational thought, Watson. Neither of us would ever be swept up in such a maelstrom of emotion and disaster."

"No man can predict his future -- or his fate," I said quietly. "No man can ever understand the needs and agonies of another human heart -- or its inner afflictions."

"Now you are being melodramatic, my boy," said Holmes. "You feel for this boy and so you begin to empathize with his plight. But you are much too reasonable a fellow ever to fall into such a trap -- and so am I. We will both do our best for Charles Griffith -- you for his body and I for his situation -- but do not begin to believe that you can cure all of his ills -- or all the ills of the world. I know you wish to, Watson, but it is impossible. That path leads only to frustration and despair."

"I know." I sighed and took out my watch. It was getting late and in the morning we were to get into Mycroft's carriage and begin that long, wet journey back to London. But I did not wish to quit the library -- at least not yet. This might be my only opportunity to visit Holmes' boyhood home, my last chance to learn something of my reticent friend's early life. "I'm sorry I did not visit the hives with you yesterday. You seem to put great stock in them."

Holmes' eyes glittered. "Bees are deucedly fascinating, my dear fellow! The order of their society! The logic of their behavior! They are without language, without intellect, and even without souls, all the elements we mortal men deem necessary for civilization, yet bees have something we might call a civilization. They work, they cooperate, each in his own place, and each for the good of all!"

"Lord, Holmes," I said. "You sound like a perfect socialist! I admit bees appear admirable creatures, but do they create great works of art? Compose beautiful music? Write uplifting literature?"

"They build," Holmes asserted. "Their hives are amazing works of architecture. And the honey they create is sweeter than any food man can devise. When I was a lad I used to spend hours observing their comings and goings. Mankind would do well to emulate them."

"Your passion is evident," I said. "I'm surprised you did not pursue biology or another study that related to the natural sciences."

Holmes reached for his pipe and filled it. He had smoked a small bowl at the table after dinner, but since we had retired to the library with the sherry decanter, he had refrained until now. "The natural sciences -- that was my father's realm."

"Was it?" Now he had my interest.

"He loved the natural world and made it his chief study," said Holmes, puffing thoughtfully. "He was also a talented artist, as were all those in the Vernet family. He took his degree from Cambridge at 17 and immediately began to travel, searching out strange flora and fauna and drawing them. That's how he found the woman who became my mother. She was also an artist and a naturalist."

"They sound perfectly suited," I said.

"They were," Holmes replied. "They met in Boston. My father gave a lecture at Harvard and my mother attended."

"She was residing in America at the time?"

"She was American," Holmes corrected. "Her father was a professor at that university and a great believer in the education of females. My mother was a noted Bluestocking and a confirmed spinster until she met my father. He brought her back to Sherringford and they were wed. My grandfather was not at all pleased, but he could hardly protest his only surviving son's selection of a bride, especially considering my father was the product of my grandfather's illicit liaison with Mlle. Yvonne."

"Quite," I coughed.

"Mycroft was born within a year of their marriage," Holmes continued. "I came along seven years later. Neither of my parents were -- how shall I put it? -- enamoured of children. They loved travel and they loved their studies. My brother and I placed after those pursuits by some distance. But we never felt any lack. We had first-rate tutors in every subject, but especially the sciences. My parents were constantly abroad and my grandfather always in London with his various mistresses, but Mycroft and I were free to do what we liked, as long as we devoted part of our time to study. And we both avoided being sent away to a noxious public school full of snobs and junior sodomites. For that I will always be grateful to the old man."

"It sounds like a lonely life." I could not help but think of my own forlorn hours at school, my mother dead and my father and brother little concerned about my welfare or happiness.

"Solitary, but not lonely," Holmes shrugged. "I made my own life even as a boy. I studied and in my spare time I read the popular papers -- the servants gladly obtained for me the most lurid of the penny presses in return for a small fraction of my allowance. Crime in all its aspects intrigued me from an early age. I remember reading 'Macbeth' and thinking that the man might well have gotten away with his murder if only he had not depended on an hysterical female as his partner in crime!"

I laughed out loud at that. "You would have made a very singular literary critic, Holmes!"

"Thank you, my dear boy," he said, bowing in my direction. "I take that as a high compliment, especially from a man whose taste in literature is impeccable."

"Hardly," I sniffed.

"I mean it, my boy. There is no being on earth whose approbation I treasure more," he returned. He was staring into the dwindling fire, his fine profile sharpened by the shadows of the evening. "You ask if I were ever lonely as a boy. I did not understand then that I was missing the companionship other boys take for granted. Mycroft and I took our singularity as the natural order of things and we turned to each other when we needed the encouragement that might otherwise been offered by a parent or adult mentor. But you have met my brother -- he's not a warm or easy man and he was not warm or easy as a youth. He was not someone in whom I could confide my thoughts or dreams. In fact, I never considered that such a person might exist. A person in whom I could always rely, always trust, and always know that he would forgive, no matter what damnable offense I might commit in my bumbling, blockheaded manner."

"Holmes, I..."

"I think you should go up to bed," he said, cutting me off. "We will make an early start tomorrow and there is much work to do in London if the Griffith case is to proceed. We could tarry here another day or even a week, but what help will that be to Young Charles?"

"None whatsoever," I acknowledged. I stood and felt a cramp in my bad leg. I shook it out as best I was able, but I was glad a hot bath awaited me upstairs. "Are you coming up?"

"Shortly," said Holmes, relighting his pipe. "I need to puzzle over a few things before I'm ready to be claimed by sleep."

I left him in his chair and made my way into the main hall.

"Oh, Doctor!" said Mrs. Murray, the housekeeper. "Your tub is ready. James and Henry have filled it for you. Mr. Lovell says you and Mr. Sherlock are leaving in the morning."

"Yes, Mrs. Murray. Business takes us back to London," I said. "But I hope we will return for a longer stay, perhaps this summer."

She smiled. "We are not used to visitors, but you and the young master are always welcome!"

It sounded odd to hear Holmes referred to as the young master. I tried to picture him as a boy, but never had a man seemed to have been born fully formed as did Sherlock Holmes.

"Did you know Mr. Sherlock as a boy?"

"That I did!" she offered. "And Mr. Mycroft, too. I started in service in this house when I was 13, as an under-parlourmaid, so I've seen many doings in this family. Come here, Doctor." She beckoned me to the stairway and held her candle aloft. "This is Mr. Mycroft and Mr. Sherlock as lads." She showed me a portrait of two children in velvet jackets, their faces solemn. Mycroft even then was a stout fellow, while Holmes had bright, knowing eyes that pierced right to the heart.

"They look melancholy," I pronounced.

"Perhaps it seems so," she conceded. "But they were full of pranks as well. Mr. Sherlock was as mischievous a lad as any in the county. I always thought he had a touch of the devil in him. The old Earl used to say it was because his mother was an American -- that she must be descended from a tribe of wild Indians to have whelped such an unruly pup!"

I snorted at that characterization. "From what I hear of the Earl, he should have been the last person to upbraid anyone for their bad behavior!"

Mrs. Murray covered her mouth in forbidden glee. "Oh, Doctor, His Lordship was a Tartar, that he was! But don't be saying that I told you so!" She moved up the stairs. "Here's the old gentleman himself."

The Earl, Holmes' grandfather, looked a right reprobate. He was dressed somberly, but had the flushed face of a heavy drinker and the red-rimmed, leering eyes of a practiced sinner.

"He doesn't look like either of the brothers," I commented.

"Mr. Mycroft is the picture of his father, except more..." Mrs. Murray hesitated, unwilling to say a word against her master.

"Upholstered?" I suggested. But what I meant was corpulent.

"Yes, indeed," she nodded. "Here is Mr. Osric and his bride." She pointed to a smaller portrait of a young couple, the man standing behind the seated woman, his hand resting lightly on her shoulder. They both looked bland and nondescript, hardly the parents of two brilliant minds such as the Holmes brothers. "Mr. Sherlock favors... his grandmother's side of the family."

"You mean the Earl's mistress' family? The Vernets?"

"Yes," said the housekeeper. "There's small portrait of the Mademoiselle in the Earl's bedroom in the other wing, painted by her brother. They say she came from a family of famous artists over in France. Mr. Osric certainly loved to make pictures. There are boxes and boxes of drawings and paintings he and his lady made on their travels, but they are stored away and no one looks at them nowadays."

"Did Holmes or Mycroft ever show an affinity for drawing?" It seemed curious that neither of them had inherited the talent, with such a strong inclination on both sides.

"Mr. Sherlock did, when he was a small lad, but he never took it up when he got bigger," said Mrs. Murray as we continued up the stairway. "He was a funny boy -- he had his likes and dislikes right from the start. If he couldn't be the best at something, he didn't want to do it at all. It was like that business with his mathematics tutor."

I frowned. "What business was that?"

"Mr. Sherlock showed a great ability for numbers and such like, so the old Earl brought a friend of Mr. Mycroft's from Cambridge who was supposedly a great scholar in that subject to tutor the lad. Mr. Sherlock was only 14 or thereabouts, but he was already as sharp as any grown man. He took to Mr. Mycroft's friend like I've never seen him take to anyone. For months they were inseparable. And then..." she paused, a troubled expression on her face.

"Then what?"

"I don't know, Doctor. Mr. Sherlock suddenly took against his tutor. They must have had a falling out over some little thing or other. You know how boys are -- they take things to heart. Mr. Sherlock refused to study mathematics anymore. He told the old Earl that if he couldn't be the best, then he'd rather be nothing. That put the Earl into a fury! Then the lad said he wouldn't be in the same house with his tutor and demanded he be sent away. The poor man needed the money, I think, which was why he was teaching the boy in the first place. Scholars are not rich gentlemen as rule, are they, Doctor?"

"No, they are not," I allowed.

"In the end the tutor was dismissed," said the housekeeper. "Afterwards Mr. Sherlock was even more obstinate and solitary in his ways. He was even short with the servants, which he'd never been before. Whenever the Earl or Mr. Mycroft tried to get out of him what had happened between him and his tutor, his face clouded over and he dug in his heels and would say not a word about it. He was ever a stubborn young lad."

"And equally stubborn as a man," I confirmed.

"You would know that as well as anyone, Doctor," said Mrs. Murray. "Being his... his only real friend. I mean, that ever he's had."

"I suppose I am," I replied. We stopped before my chamber door.

"Keep watch over him, Doctor," Mrs. Murray entreated me. "Mr. Sherlock never had anyone who cared for him enough to do that. But I think you care enough. As a friend, I mean," she added quickly. "A good and kindly friend."

"I promise to do my best, good lady," I said, bidding her good-night.

I thought about Mrs. Murray's words as I undressed and prepared for my bath. That no one had ever cared enough for Holmes, as a boy or as a man. Until I came along. But what was my responsibility to my friend? And did he understand how that caring sometimes skirted what was decent and honourable -- at least in my own conflicted mind?

I was glad at the thought that we would soon return to 221b and resume our ordinary existence.

Little did I know how wrong I was to be at that supposition.

***

Title: "A Conversation by a Dwindling Fire"

Author: Gaedhal

Pairing/Characters: Sherlock Holmes/Dr. John H. Watson; Mrs. Murray.

Rating: R

Spoilers: None

Notes/Warnings: "Sherlock Holmes" (2009) Universe. Set before the Blackwood case.

Disclaimer: This is for fun, not profit. Enjoy.

Summary: Conversation is broadening.

First chapter here:

1. "A Walk to Regent's Park"

http://gaedhal.livejournal.com/367955.html

Previous chapter here:

18. "An Interview with a Young Client"

http://gaedhal.livejournal.com/376625.html

New Chapter here:

By Gaedhal

"A sorry business," I mused, as Holmes and I sat in the library that evening. It was filthy weather outside, with the rain coming down in torrents, and the chill that infested the old house had caused us to draw close to the hearth in search of warmth.

"Men who prey on the weaknesses of their fellows are a sorry lot," Holmes concurred. "Young Griffith is a mere lad, unused to the true evils of the world, and so he was ripe to be exploited. Unfortunately, Major Griffith is an obstinate ass and unlikely to give his son the kind of guidance he will need to avoid such contretemps in the future."

"Charles is a tender-hearted boy," I commented. "He seemed more concerned with the fate of his little paramour than he was with his own future."

"The boy is a fool," Holmes said dismissively. "He imagines he's in love and so is willing to sacrifice all -- his fortune, his good name, even his life. Such poppycock!"

"Perhaps he is in love," I said, watching the last log split and send a shower of sparks up the flue. "The object may seem to us unworthy, but who can peer into a boy's soul? Or a man's?"

"Love!" Holmes almost spat out the word. "Romantic drivel! Thank heaven you and I are men of rational thought, Watson. Neither of us would ever be swept up in such a maelstrom of emotion and disaster."

"No man can predict his future -- or his fate," I said quietly. "No man can ever understand the needs and agonies of another human heart -- or its inner afflictions."

"Now you are being melodramatic, my boy," said Holmes. "You feel for this boy and so you begin to empathize with his plight. But you are much too reasonable a fellow ever to fall into such a trap -- and so am I. We will both do our best for Charles Griffith -- you for his body and I for his situation -- but do not begin to believe that you can cure all of his ills -- or all the ills of the world. I know you wish to, Watson, but it is impossible. That path leads only to frustration and despair."

"I know." I sighed and took out my watch. It was getting late and in the morning we were to get into Mycroft's carriage and begin that long, wet journey back to London. But I did not wish to quit the library -- at least not yet. This might be my only opportunity to visit Holmes' boyhood home, my last chance to learn something of my reticent friend's early life. "I'm sorry I did not visit the hives with you yesterday. You seem to put great stock in them."

Holmes' eyes glittered. "Bees are deucedly fascinating, my dear fellow! The order of their society! The logic of their behavior! They are without language, without intellect, and even without souls, all the elements we mortal men deem necessary for civilization, yet bees have something we might call a civilization. They work, they cooperate, each in his own place, and each for the good of all!"

"Lord, Holmes," I said. "You sound like a perfect socialist! I admit bees appear admirable creatures, but do they create great works of art? Compose beautiful music? Write uplifting literature?"

"They build," Holmes asserted. "Their hives are amazing works of architecture. And the honey they create is sweeter than any food man can devise. When I was a lad I used to spend hours observing their comings and goings. Mankind would do well to emulate them."

"Your passion is evident," I said. "I'm surprised you did not pursue biology or another study that related to the natural sciences."

Holmes reached for his pipe and filled it. He had smoked a small bowl at the table after dinner, but since we had retired to the library with the sherry decanter, he had refrained until now. "The natural sciences -- that was my father's realm."

"Was it?" Now he had my interest.

"He loved the natural world and made it his chief study," said Holmes, puffing thoughtfully. "He was also a talented artist, as were all those in the Vernet family. He took his degree from Cambridge at 17 and immediately began to travel, searching out strange flora and fauna and drawing them. That's how he found the woman who became my mother. She was also an artist and a naturalist."

"They sound perfectly suited," I said.

"They were," Holmes replied. "They met in Boston. My father gave a lecture at Harvard and my mother attended."

"She was residing in America at the time?"

"She was American," Holmes corrected. "Her father was a professor at that university and a great believer in the education of females. My mother was a noted Bluestocking and a confirmed spinster until she met my father. He brought her back to Sherringford and they were wed. My grandfather was not at all pleased, but he could hardly protest his only surviving son's selection of a bride, especially considering my father was the product of my grandfather's illicit liaison with Mlle. Yvonne."

"Quite," I coughed.

"Mycroft was born within a year of their marriage," Holmes continued. "I came along seven years later. Neither of my parents were -- how shall I put it? -- enamoured of children. They loved travel and they loved their studies. My brother and I placed after those pursuits by some distance. But we never felt any lack. We had first-rate tutors in every subject, but especially the sciences. My parents were constantly abroad and my grandfather always in London with his various mistresses, but Mycroft and I were free to do what we liked, as long as we devoted part of our time to study. And we both avoided being sent away to a noxious public school full of snobs and junior sodomites. For that I will always be grateful to the old man."

"It sounds like a lonely life." I could not help but think of my own forlorn hours at school, my mother dead and my father and brother little concerned about my welfare or happiness.

"Solitary, but not lonely," Holmes shrugged. "I made my own life even as a boy. I studied and in my spare time I read the popular papers -- the servants gladly obtained for me the most lurid of the penny presses in return for a small fraction of my allowance. Crime in all its aspects intrigued me from an early age. I remember reading 'Macbeth' and thinking that the man might well have gotten away with his murder if only he had not depended on an hysterical female as his partner in crime!"

I laughed out loud at that. "You would have made a very singular literary critic, Holmes!"

"Thank you, my dear boy," he said, bowing in my direction. "I take that as a high compliment, especially from a man whose taste in literature is impeccable."

"Hardly," I sniffed.

"I mean it, my boy. There is no being on earth whose approbation I treasure more," he returned. He was staring into the dwindling fire, his fine profile sharpened by the shadows of the evening. "You ask if I were ever lonely as a boy. I did not understand then that I was missing the companionship other boys take for granted. Mycroft and I took our singularity as the natural order of things and we turned to each other when we needed the encouragement that might otherwise been offered by a parent or adult mentor. But you have met my brother -- he's not a warm or easy man and he was not warm or easy as a youth. He was not someone in whom I could confide my thoughts or dreams. In fact, I never considered that such a person might exist. A person in whom I could always rely, always trust, and always know that he would forgive, no matter what damnable offense I might commit in my bumbling, blockheaded manner."

"Holmes, I..."

"I think you should go up to bed," he said, cutting me off. "We will make an early start tomorrow and there is much work to do in London if the Griffith case is to proceed. We could tarry here another day or even a week, but what help will that be to Young Charles?"

"None whatsoever," I acknowledged. I stood and felt a cramp in my bad leg. I shook it out as best I was able, but I was glad a hot bath awaited me upstairs. "Are you coming up?"

"Shortly," said Holmes, relighting his pipe. "I need to puzzle over a few things before I'm ready to be claimed by sleep."

I left him in his chair and made my way into the main hall.

"Oh, Doctor!" said Mrs. Murray, the housekeeper. "Your tub is ready. James and Henry have filled it for you. Mr. Lovell says you and Mr. Sherlock are leaving in the morning."

"Yes, Mrs. Murray. Business takes us back to London," I said. "But I hope we will return for a longer stay, perhaps this summer."

She smiled. "We are not used to visitors, but you and the young master are always welcome!"

It sounded odd to hear Holmes referred to as the young master. I tried to picture him as a boy, but never had a man seemed to have been born fully formed as did Sherlock Holmes.

"Did you know Mr. Sherlock as a boy?"

"That I did!" she offered. "And Mr. Mycroft, too. I started in service in this house when I was 13, as an under-parlourmaid, so I've seen many doings in this family. Come here, Doctor." She beckoned me to the stairway and held her candle aloft. "This is Mr. Mycroft and Mr. Sherlock as lads." She showed me a portrait of two children in velvet jackets, their faces solemn. Mycroft even then was a stout fellow, while Holmes had bright, knowing eyes that pierced right to the heart.

"They look melancholy," I pronounced.

"Perhaps it seems so," she conceded. "But they were full of pranks as well. Mr. Sherlock was as mischievous a lad as any in the county. I always thought he had a touch of the devil in him. The old Earl used to say it was because his mother was an American -- that she must be descended from a tribe of wild Indians to have whelped such an unruly pup!"

I snorted at that characterization. "From what I hear of the Earl, he should have been the last person to upbraid anyone for their bad behavior!"

Mrs. Murray covered her mouth in forbidden glee. "Oh, Doctor, His Lordship was a Tartar, that he was! But don't be saying that I told you so!" She moved up the stairs. "Here's the old gentleman himself."

The Earl, Holmes' grandfather, looked a right reprobate. He was dressed somberly, but had the flushed face of a heavy drinker and the red-rimmed, leering eyes of a practiced sinner.

"He doesn't look like either of the brothers," I commented.

"Mr. Mycroft is the picture of his father, except more..." Mrs. Murray hesitated, unwilling to say a word against her master.

"Upholstered?" I suggested. But what I meant was corpulent.

"Yes, indeed," she nodded. "Here is Mr. Osric and his bride." She pointed to a smaller portrait of a young couple, the man standing behind the seated woman, his hand resting lightly on her shoulder. They both looked bland and nondescript, hardly the parents of two brilliant minds such as the Holmes brothers. "Mr. Sherlock favors... his grandmother's side of the family."

"You mean the Earl's mistress' family? The Vernets?"

"Yes," said the housekeeper. "There's small portrait of the Mademoiselle in the Earl's bedroom in the other wing, painted by her brother. They say she came from a family of famous artists over in France. Mr. Osric certainly loved to make pictures. There are boxes and boxes of drawings and paintings he and his lady made on their travels, but they are stored away and no one looks at them nowadays."

"Did Holmes or Mycroft ever show an affinity for drawing?" It seemed curious that neither of them had inherited the talent, with such a strong inclination on both sides.

"Mr. Sherlock did, when he was a small lad, but he never took it up when he got bigger," said Mrs. Murray as we continued up the stairway. "He was a funny boy -- he had his likes and dislikes right from the start. If he couldn't be the best at something, he didn't want to do it at all. It was like that business with his mathematics tutor."

I frowned. "What business was that?"

"Mr. Sherlock showed a great ability for numbers and such like, so the old Earl brought a friend of Mr. Mycroft's from Cambridge who was supposedly a great scholar in that subject to tutor the lad. Mr. Sherlock was only 14 or thereabouts, but he was already as sharp as any grown man. He took to Mr. Mycroft's friend like I've never seen him take to anyone. For months they were inseparable. And then..." she paused, a troubled expression on her face.

"Then what?"

"I don't know, Doctor. Mr. Sherlock suddenly took against his tutor. They must have had a falling out over some little thing or other. You know how boys are -- they take things to heart. Mr. Sherlock refused to study mathematics anymore. He told the old Earl that if he couldn't be the best, then he'd rather be nothing. That put the Earl into a fury! Then the lad said he wouldn't be in the same house with his tutor and demanded he be sent away. The poor man needed the money, I think, which was why he was teaching the boy in the first place. Scholars are not rich gentlemen as rule, are they, Doctor?"

"No, they are not," I allowed.

"In the end the tutor was dismissed," said the housekeeper. "Afterwards Mr. Sherlock was even more obstinate and solitary in his ways. He was even short with the servants, which he'd never been before. Whenever the Earl or Mr. Mycroft tried to get out of him what had happened between him and his tutor, his face clouded over and he dug in his heels and would say not a word about it. He was ever a stubborn young lad."

"And equally stubborn as a man," I confirmed.

"You would know that as well as anyone, Doctor," said Mrs. Murray. "Being his... his only real friend. I mean, that ever he's had."

"I suppose I am," I replied. We stopped before my chamber door.

"Keep watch over him, Doctor," Mrs. Murray entreated me. "Mr. Sherlock never had anyone who cared for him enough to do that. But I think you care enough. As a friend, I mean," she added quickly. "A good and kindly friend."

"I promise to do my best, good lady," I said, bidding her good-night.

I thought about Mrs. Murray's words as I undressed and prepared for my bath. That no one had ever cared enough for Holmes, as a boy or as a man. Until I came along. But what was my responsibility to my friend? And did he understand how that caring sometimes skirted what was decent and honourable -- at least in my own conflicted mind?

I was glad at the thought that we would soon return to 221b and resume our ordinary existence.

Little did I know how wrong I was to be at that supposition.

***