Picturing History: Slightly out of Focus

Sometimes we forget how a thing looks. The precise details of an event or the faces of people we knew. Memory can be a fickle thing. But we are in luck, because we have things that can remind us, we have words, films and photographs that can show us how things were. Right?

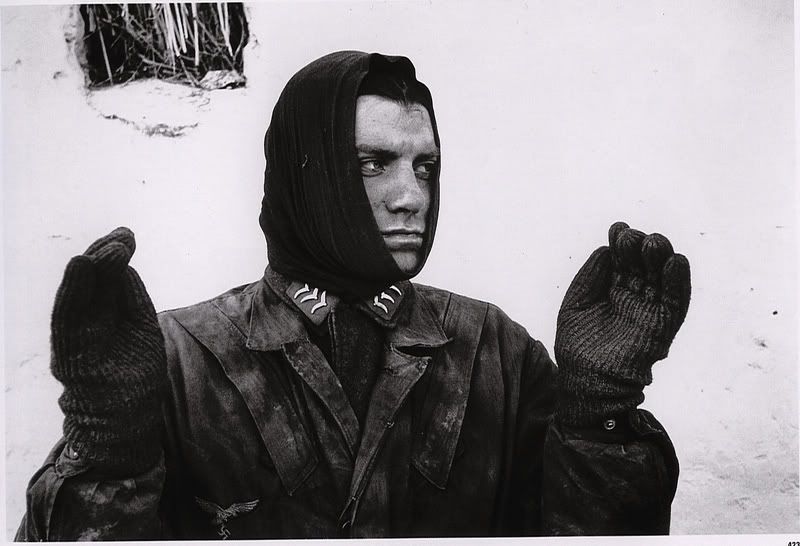

This picture was taken in Normandy on the 6. June, 1944, also known as D-Day. It was taken by Robert Capa who was known for saying that "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough." True to his own motto Capa joined the Allied landing as part of the first assault wave, armed not with a gun but a camera.

Sadly for Capa, but interestingly for posterity, Life magazine who had commissioned the pictures had a little dark room mishap, and thereby destroyed most of the film.

Of the over a hundred pictures Capa had taken, only 11 frames survived, and the photos developed a grainy, shaky feel. Life magazine printed them anyway and claimed the pictures where unclear and out of focus because Capa’s hand was shaking with excitement, and he therefore couldn’t focus properly.

Despite this the pictures became famous and have attained a role as historical documents and as witnesses to the Normandy landing. The witness roles of Capa’s photographs are so cemented that they were and are used in many history books, and give the impression that this is what the invasion looked like. See! We have photographic evidence. We have a visual witness.

But photographs are never objective. Behind the camera there is always a person- who chooses when to shoot and when to look away. A picture taken is also comprised of several subjective choices regarding composition, light, angles and so forth. So a photo might be a witness - but it is a highly subjective one.

Consider this: there is a photo of people smiling. Why are they smiling? Are they happy or are they putting on a show? A “say cheese” show? A photo has been described as a moment in time - and it truly is, but it is a moment taken out of context.

With Capa the context of Capa himself is complicated. He travelled with different divisions of the U.S. army, being in other words embedded with them. A commander of one Armour division even said they considered Capa part of battalion staff. He endured the same harsh conditions the soldiers did, and even if this speaks volumes about Capa as a person and the lengths he would go to for his art, it does not improve his stature as an objective witness. But truly, with photo I'm not sure an objective witness is possible.

Capa’s pictures were also used as visual aides for the opening scene of Saving Private Ryan (yes, that opening scene). "Saving Private Ryan" even mimicked the grainy, monochrome feel of Capra’s pictures. The same grainy feel that was a result of a darkroom mishap, more than Capa’s intention.

"Saving Private Ryan" was the predecessor and model for the HBO series Band of Brothers, and the same monochrome, grainy feel can be found in that series as well.

In a strange chain of events the commemoration celebration for D-Day held the 6th June 2005 included a BBC channel showing Band of Brothers alongside documentaries of the D-day landing. Perhaps this could be seen as some sort of full circle? That a series that was visually inspired by a film, which in turn was inspired by Capa’s partially botched photographs that were taken on D-Day proper - should now commemorate the day? Or does it just blur the lines between what is fact and what is fiction? And if yes, is this always bad?

~~~~

A big thanks to semyaza who made the comment about how we could forget how things looked - and somehow that comment started all this.

And also to applegnat who had some very good points about Troy, as well as what happens to fiction when we try to turn it into fact. Cheers! :)

ETA: Somehow the introduction fell out. *facepalm* It's there now, and hopefully it makes more sense now.

This picture was taken in Normandy on the 6. June, 1944, also known as D-Day. It was taken by Robert Capa who was known for saying that "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough." True to his own motto Capa joined the Allied landing as part of the first assault wave, armed not with a gun but a camera.

Sadly for Capa, but interestingly for posterity, Life magazine who had commissioned the pictures had a little dark room mishap, and thereby destroyed most of the film.

Of the over a hundred pictures Capa had taken, only 11 frames survived, and the photos developed a grainy, shaky feel. Life magazine printed them anyway and claimed the pictures where unclear and out of focus because Capa’s hand was shaking with excitement, and he therefore couldn’t focus properly.

Despite this the pictures became famous and have attained a role as historical documents and as witnesses to the Normandy landing. The witness roles of Capa’s photographs are so cemented that they were and are used in many history books, and give the impression that this is what the invasion looked like. See! We have photographic evidence. We have a visual witness.

But photographs are never objective. Behind the camera there is always a person- who chooses when to shoot and when to look away. A picture taken is also comprised of several subjective choices regarding composition, light, angles and so forth. So a photo might be a witness - but it is a highly subjective one.

Consider this: there is a photo of people smiling. Why are they smiling? Are they happy or are they putting on a show? A “say cheese” show? A photo has been described as a moment in time - and it truly is, but it is a moment taken out of context.

With Capa the context of Capa himself is complicated. He travelled with different divisions of the U.S. army, being in other words embedded with them. A commander of one Armour division even said they considered Capa part of battalion staff. He endured the same harsh conditions the soldiers did, and even if this speaks volumes about Capa as a person and the lengths he would go to for his art, it does not improve his stature as an objective witness. But truly, with photo I'm not sure an objective witness is possible.

Capa’s pictures were also used as visual aides for the opening scene of Saving Private Ryan (yes, that opening scene). "Saving Private Ryan" even mimicked the grainy, monochrome feel of Capra’s pictures. The same grainy feel that was a result of a darkroom mishap, more than Capa’s intention.

"Saving Private Ryan" was the predecessor and model for the HBO series Band of Brothers, and the same monochrome, grainy feel can be found in that series as well.

In a strange chain of events the commemoration celebration for D-Day held the 6th June 2005 included a BBC channel showing Band of Brothers alongside documentaries of the D-day landing. Perhaps this could be seen as some sort of full circle? That a series that was visually inspired by a film, which in turn was inspired by Capa’s partially botched photographs that were taken on D-Day proper - should now commemorate the day? Or does it just blur the lines between what is fact and what is fiction? And if yes, is this always bad?

~~~~

A big thanks to semyaza who made the comment about how we could forget how things looked - and somehow that comment started all this.

And also to applegnat who had some very good points about Troy, as well as what happens to fiction when we try to turn it into fact. Cheers! :)

ETA: Somehow the introduction fell out. *facepalm* It's there now, and hopefully it makes more sense now.