The first (official) Elseworlds: "Batman: Holy Terror"

NOTE: I offer another departure from the usual topic today because... well, I just really want to discuss this one with you guys. I can justify this with the fact that it's written by the excellent author of this great Hugo Strange story I posted a while back, and also because it's a great example of what alternate universe storytelling can do. It'll be good to keep this in mind when I look at the various alternate Two-Face stories, even the ridiculous ones where Harvey's a deranged ballet dancer, thank YOU, Mike Grell.

The best Elseworlds stories utilize the alternate reality format to gain fresh perspective on the characters and themes they represent. I've always loved the mantra which used to accompany the earliest books in this imprint:

"In Elseworlds, heroes are taken from their usual settings and put into strange times and places--some that have existed, and others that can't, couldn't, or shouldn't exist. The result is stories that make characters who are as familiar as yesterday seem as fresh as tomorrow."

I've always loved that last line. "As familiar as yesterday seem as fresh as tomorrow." So why are there so many mediocre Elseworlds stories? Why do so many follow the formula of "plug in X character in Y time setting, tell basically the same origin"? Asking "What If?" doesn't really matter if that question isn't followed by, "So What?"

That is not the case with Alan Brennert's last (and only) major DC story, Batman: Holy Terror, the first alternate universe DC story to carry the Elseworlds brand. It's that rare Elseworlds (hell, that rare story) which actually has something to say about its lead character and the alternate reality he inhabits.

In this instance, it's Batman in a Puritanical theocracy.

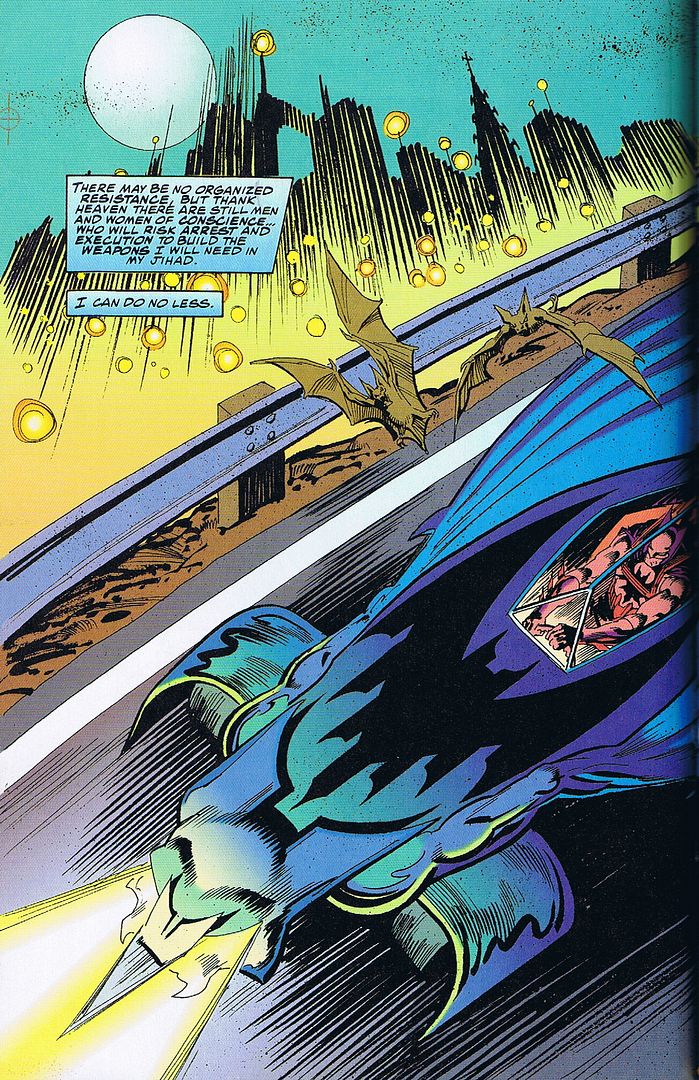

This story is not to be confused with a similarly-titled, aborted project by Frank Miller, although the two do play with similar ideas. Except Brennert's is far more subversive, even more so today than when it was published. After all, in this story, Batman is waging a Holy War. And what's another word for one of those?

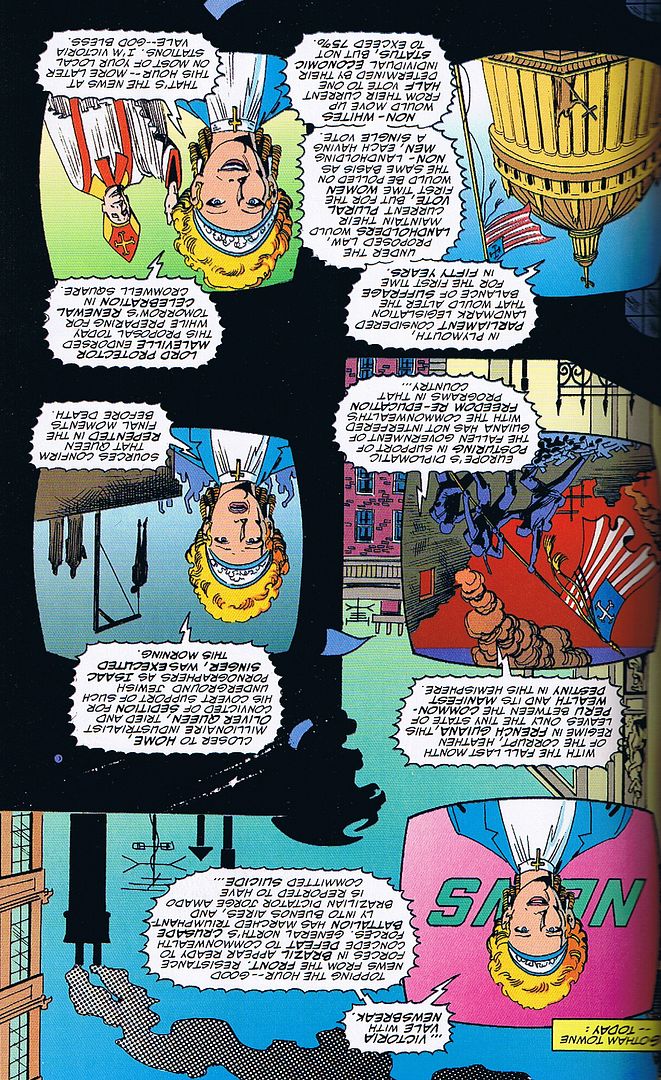

From what page, you might gather that this story takes place a century or so in the past. But fast forward to the present day:

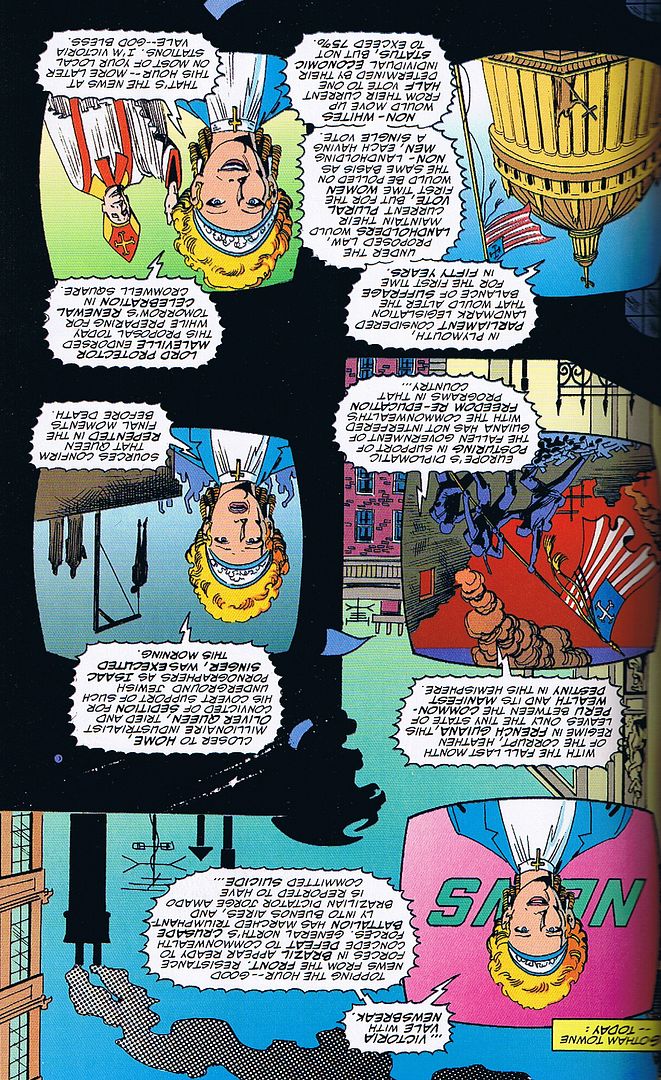

So yeah, in case you hadn't gathered, this a world where Oliver Cromwell lived on for another decade, thus leading to the Puritan Commonwealth staying in power in Britain and its colonies... including North America and, therefore, Gotham Towne.

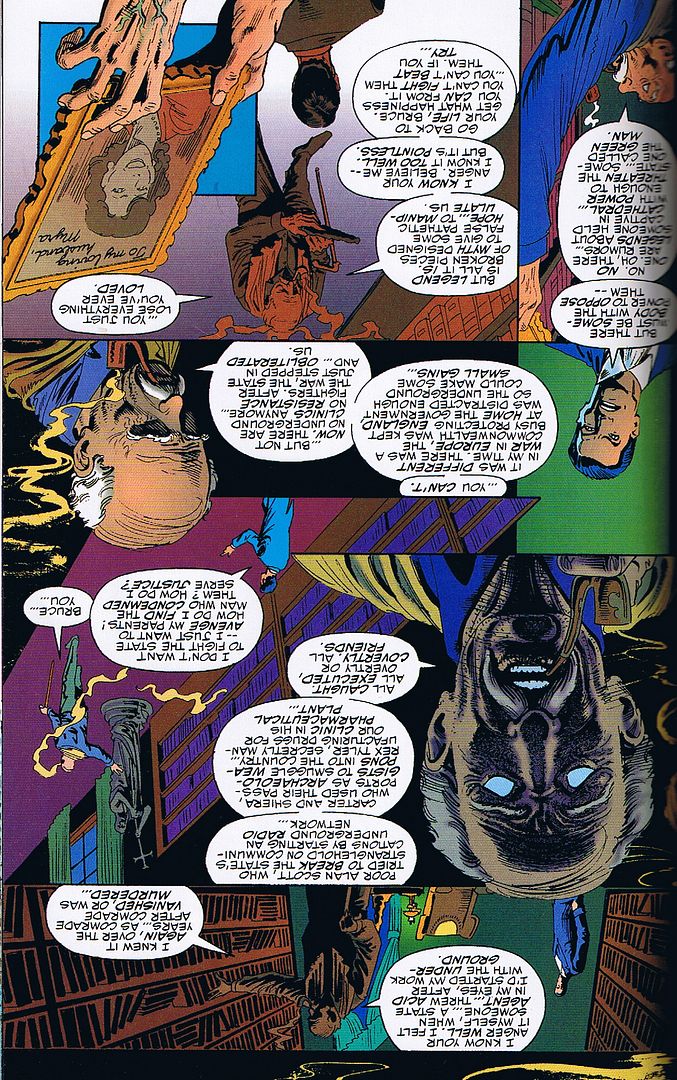

I find it interesting how almost all of the names Brennert references are real people: Isaac Singer, Jorge Amado, and presumably Ollie North. This indicates a more direct parallel to our own real world rather that being strictly in the DCU, even with the mention of Ollie's sad fate. And really, even in an alternate universe, who really thinks that Oliver Queen repented? I sure as hell don't.

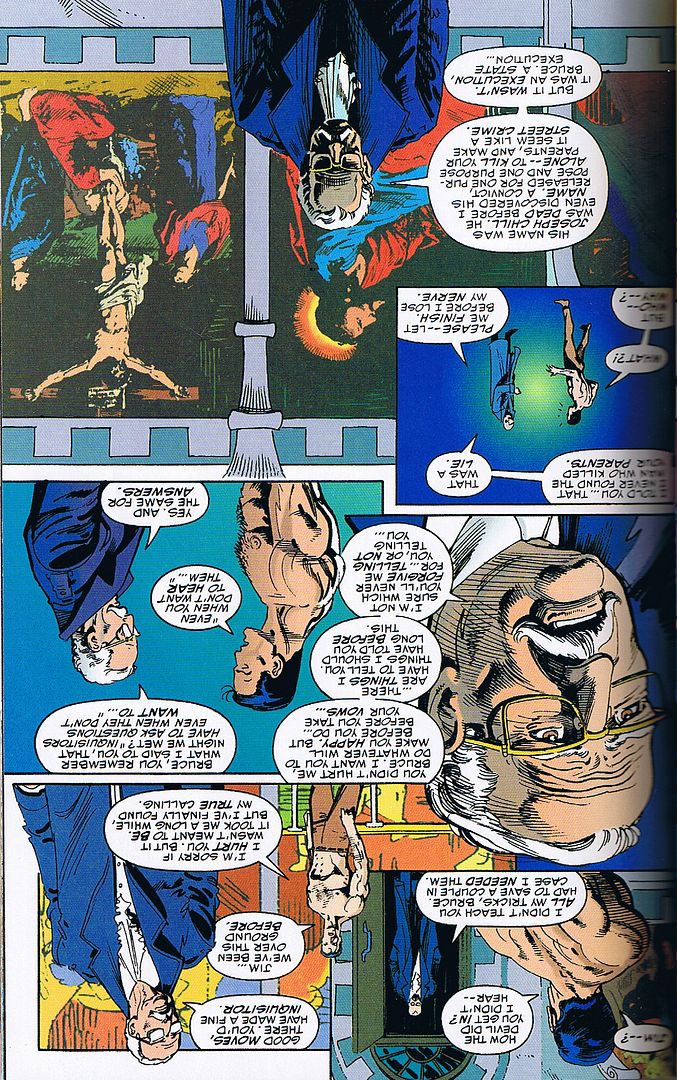

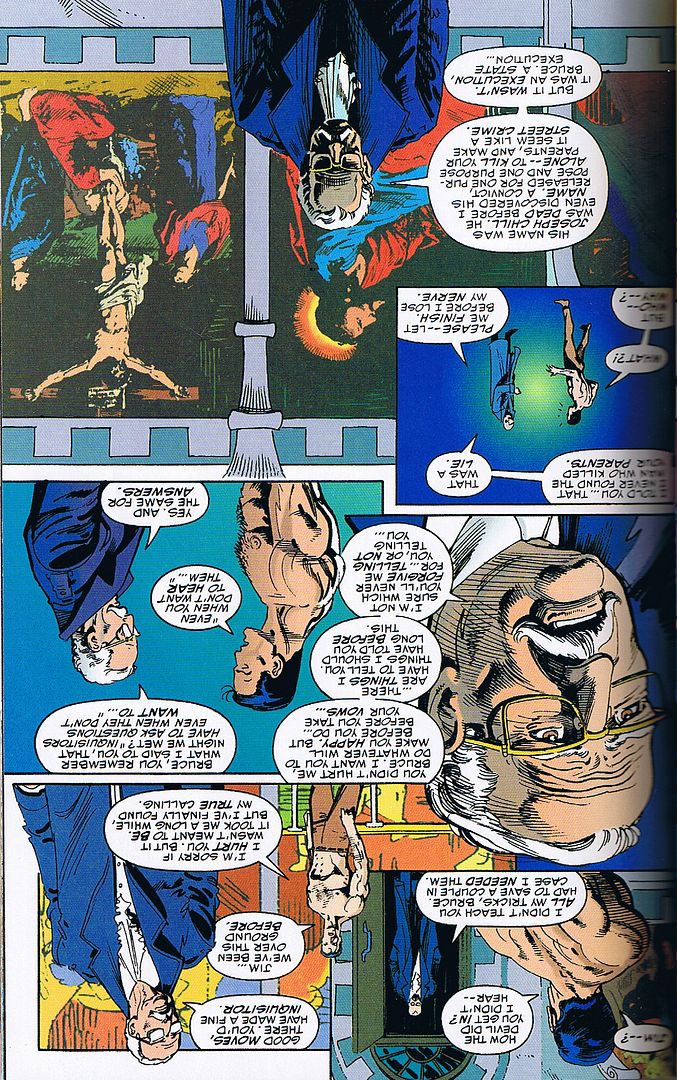

But where's Bruce in all this? We're introduced to the adult Bruce Wayne saying goodbye to Alfred, as Bruce is about to leave Wayne Manor to join the Priesthood. Bruce has actually found peace in this new path, having abandoned his old "dead-end" dream of being a gymnast. For nostalgia's sake, he practices a few moves in the gym, and an outside voice remarks, "Lost none of your form, I see."

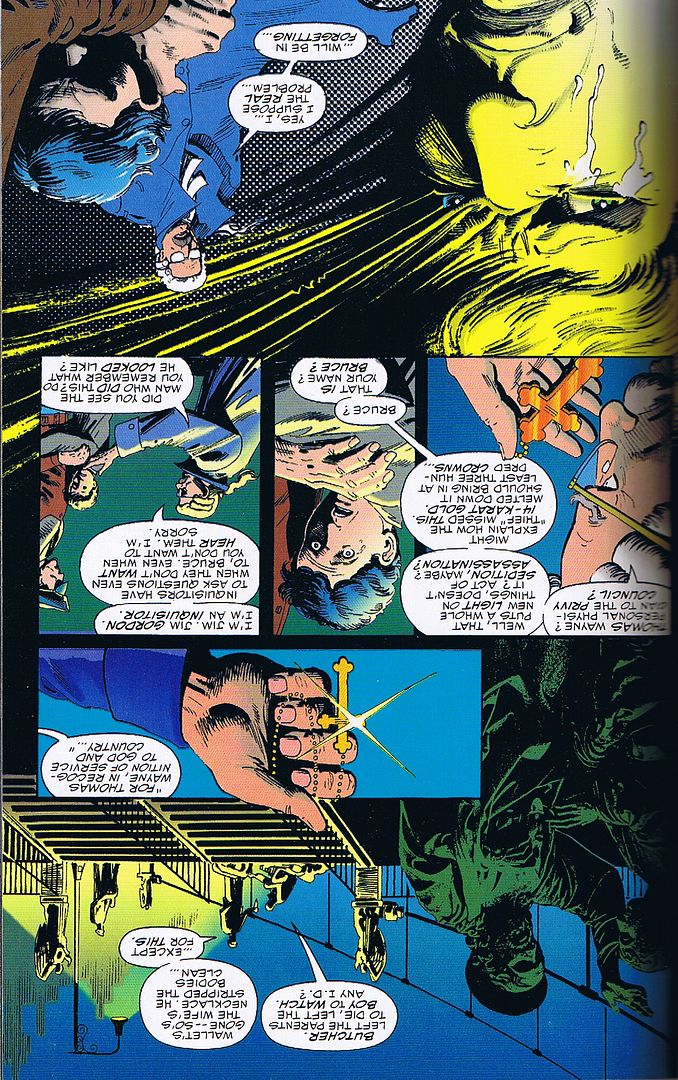

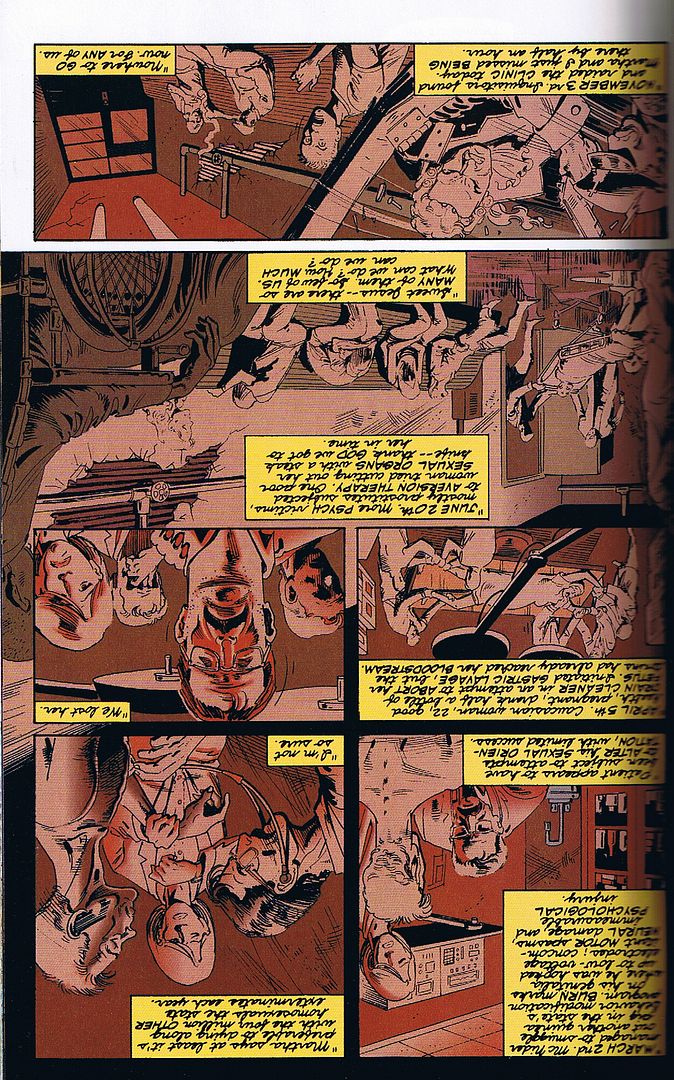

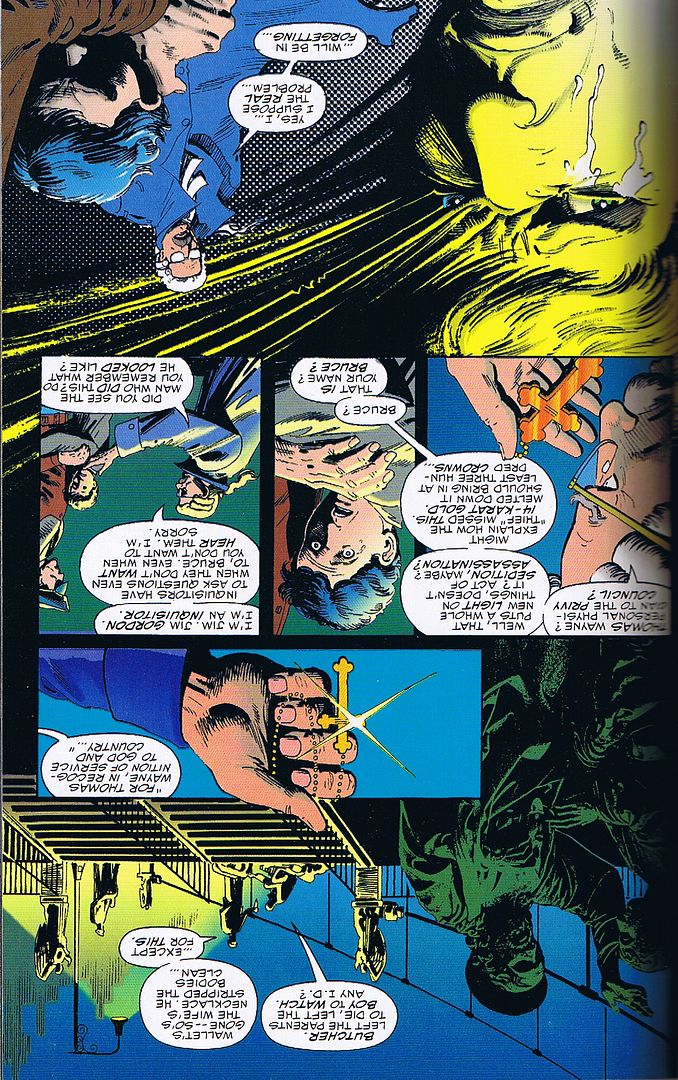

In Gordon's defense, Brennert wrote a whole scene with a magistrate insinuating threats against Gordon's family if he perused the Chill investigation. Also, another neat little touch: Gordon was then newly transferred in from "New Amsterdam."

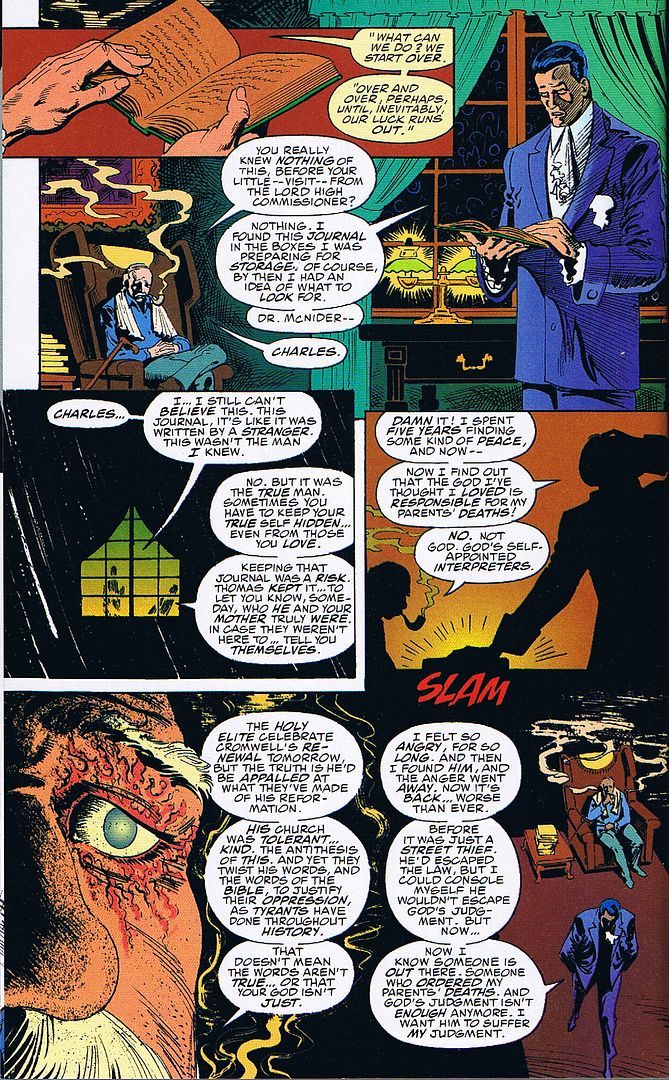

If you're a DC fan, the name Dr. Charles McNider, may ring a bell...

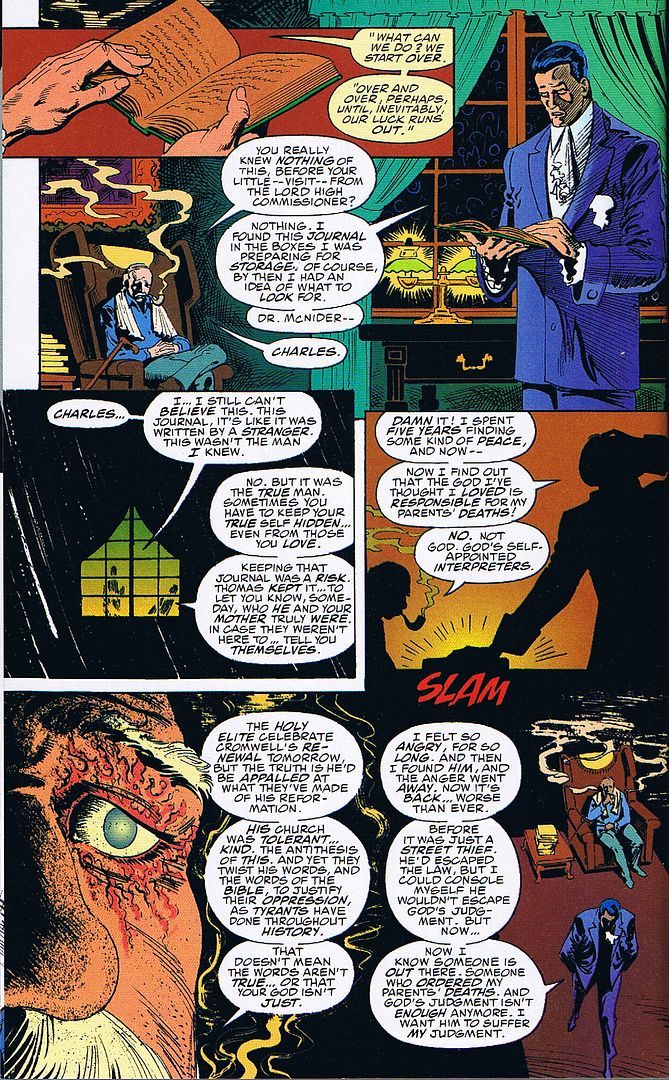

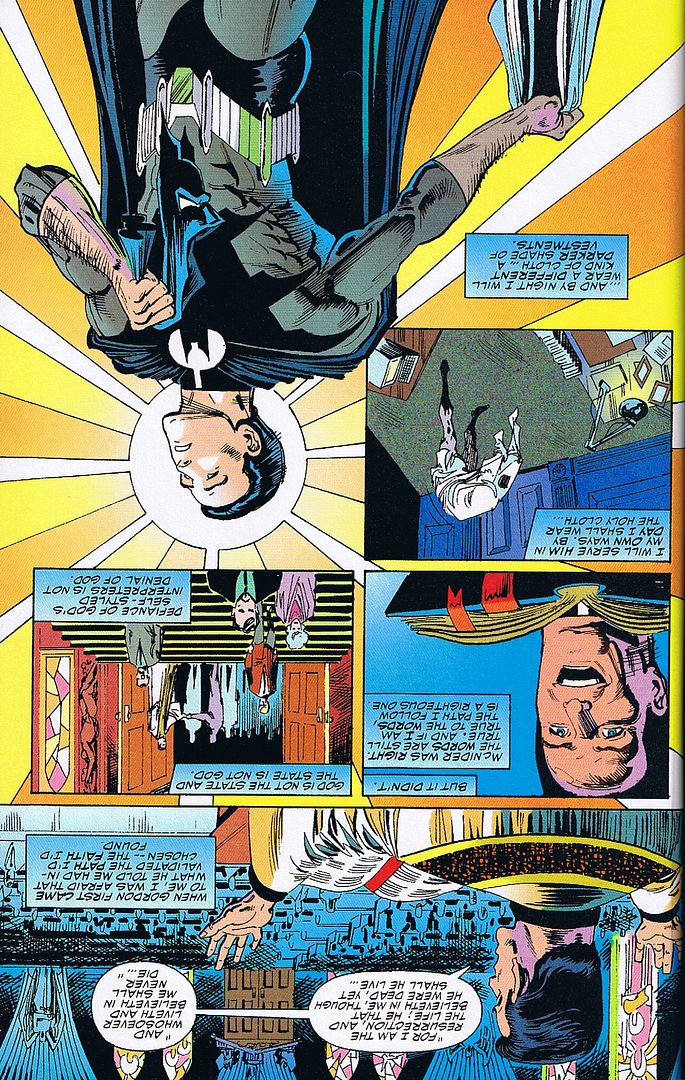

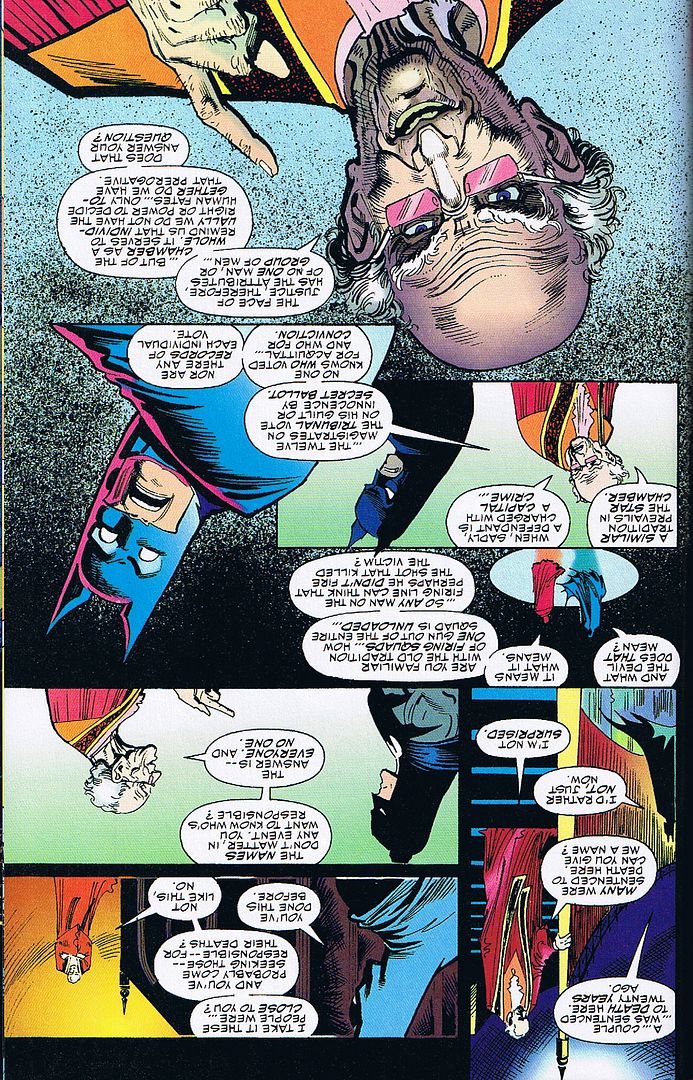

I don't know a ton about Cromwell's history, but from what little I know, is there any indication that Brennert was being ironic in having McNider refer to Cromwell's church as "tolerant" and "kind"? If so, it adds a subtle layer of complexity to why Bruce doesn't end up abandoning his faith itself.

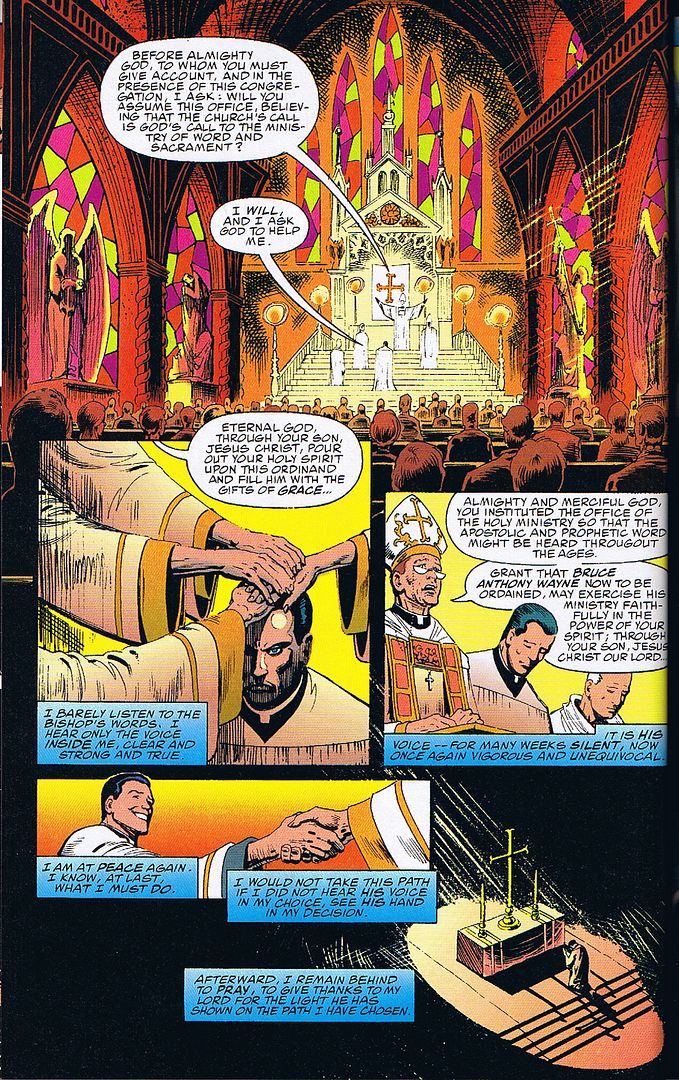

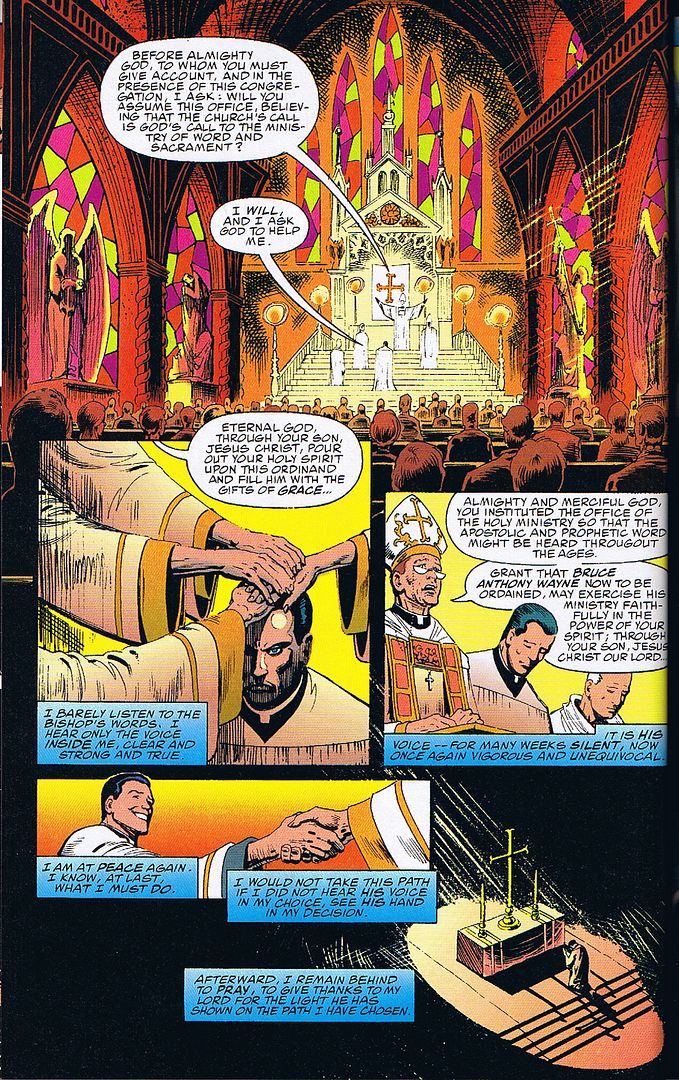

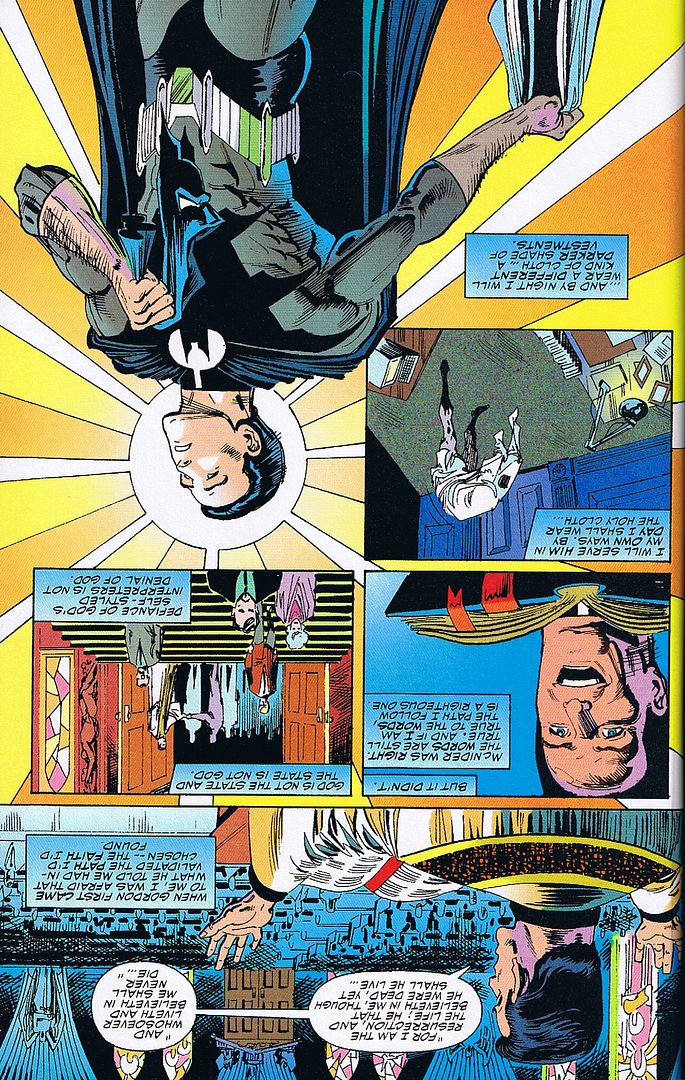

This story could easily have been about Bruce experiencing a loss of faith, and waging his war against the Theocracy in the name of secularism and reason, but it doesn't go that route. We see that right away on the day of Bruce's confirmation:

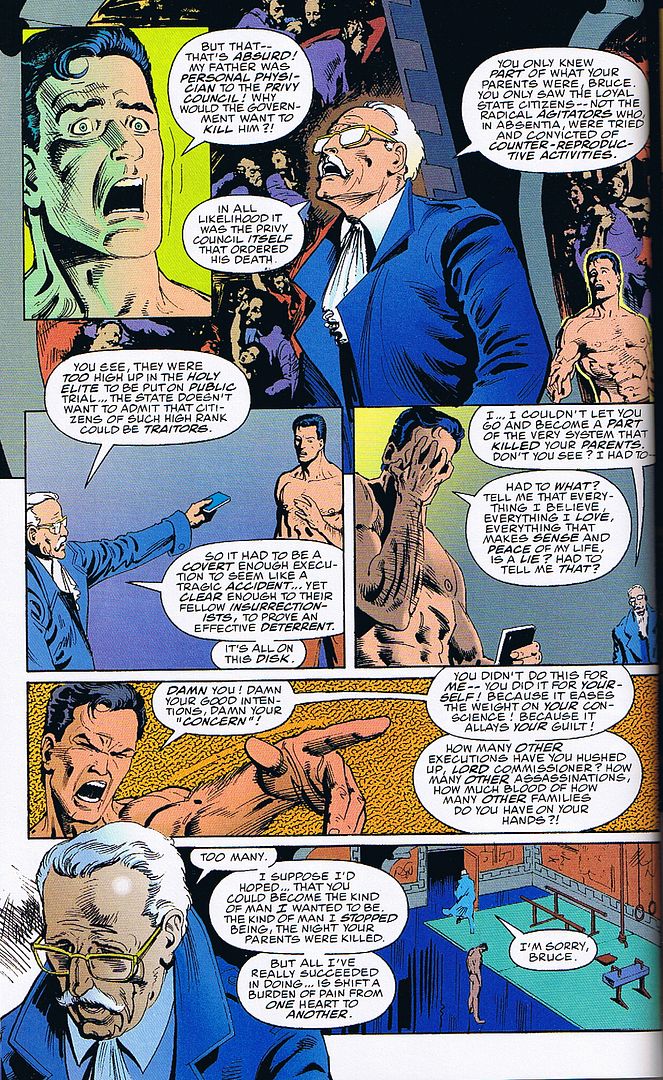

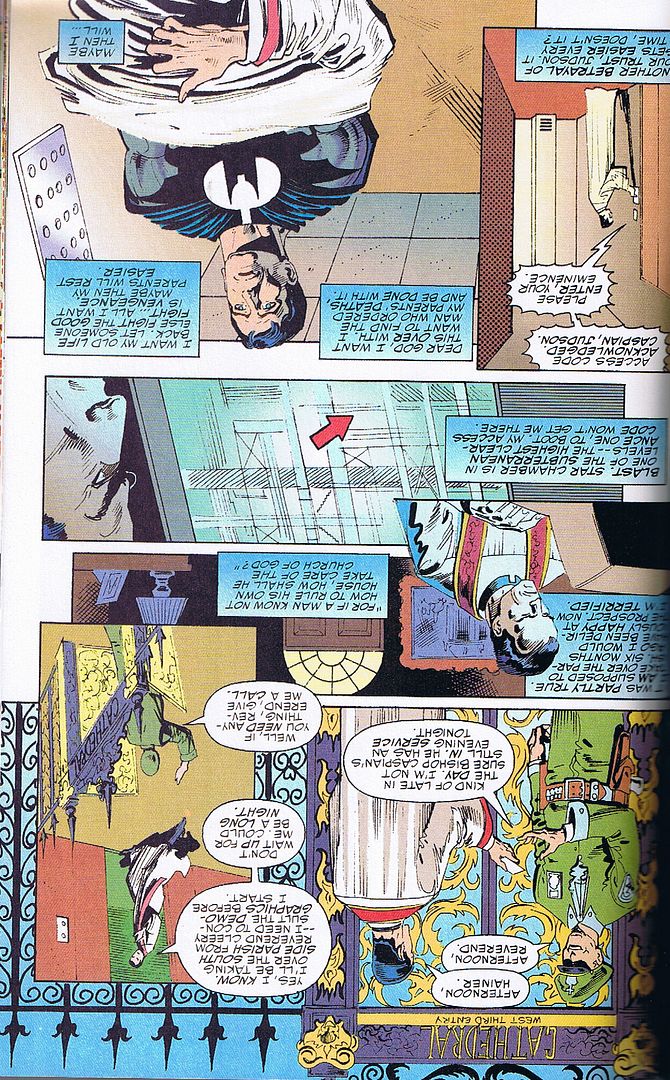

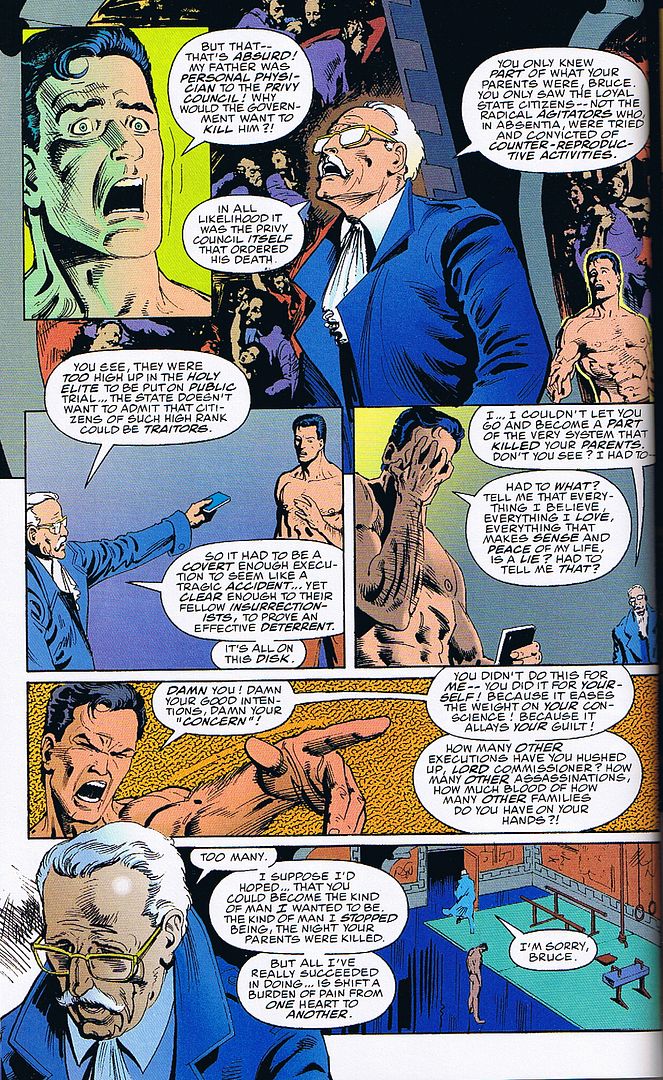

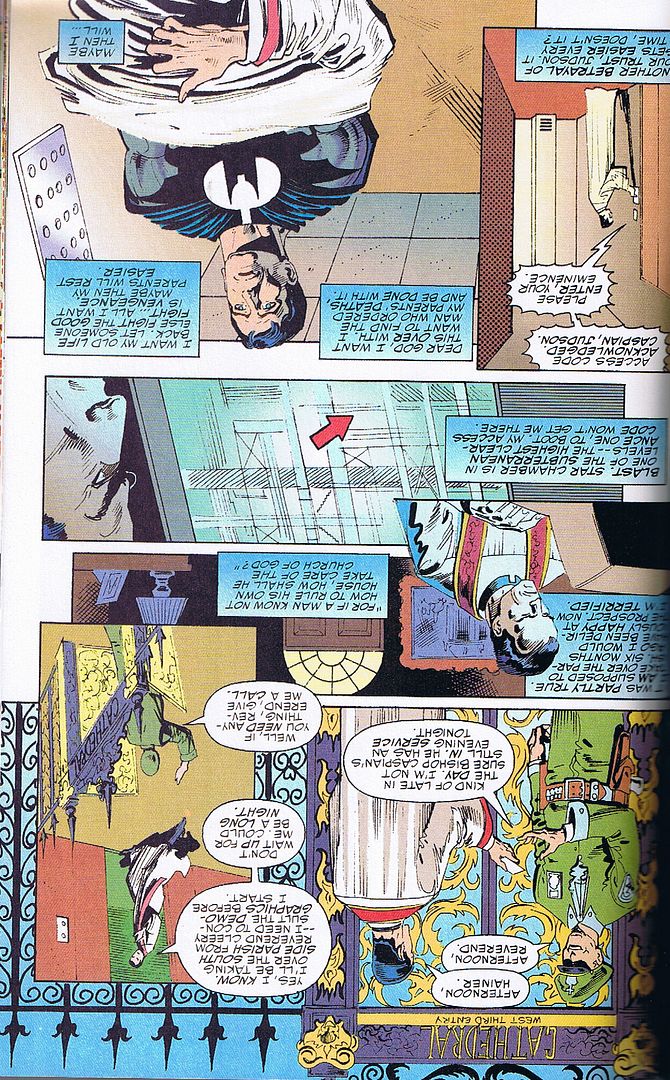

The Bishop, by the way, is none other than Judson Caspian, AKA the Reaper from Batman: Year Two, although the art bears no resemblance to the same character. We actually learn his name when we see Bruce hacking into Bishop Caspian's PC, which twinges at Bruce's conscience. He genuinely dislikes betraying the confidence of a "good man, an honorable man," but he has to find out who ordered his parents' execution.

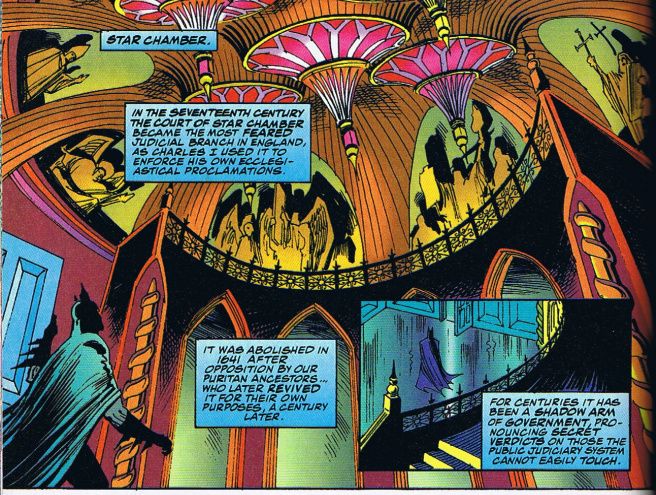

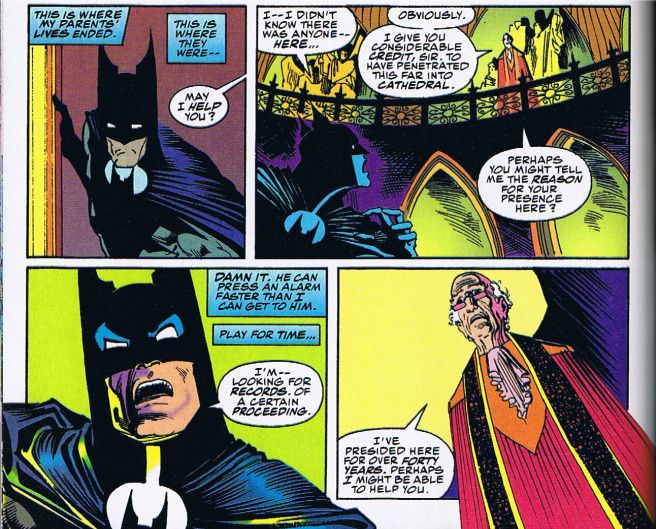

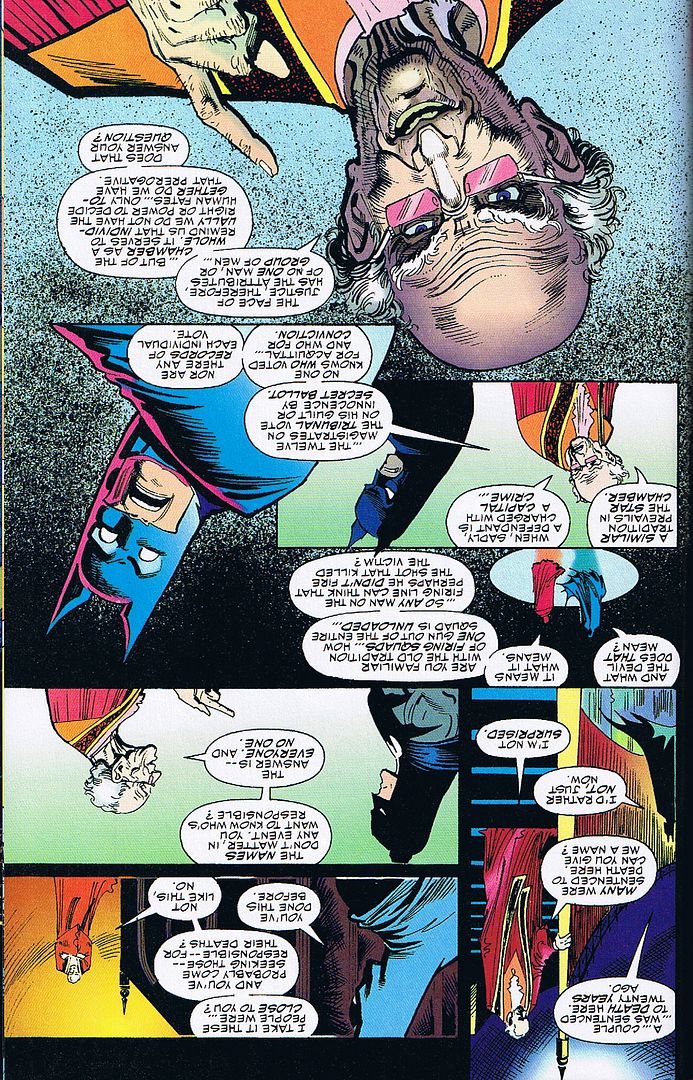

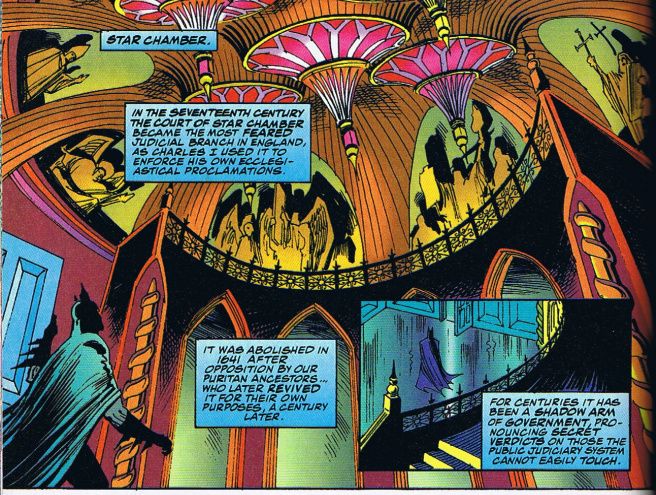

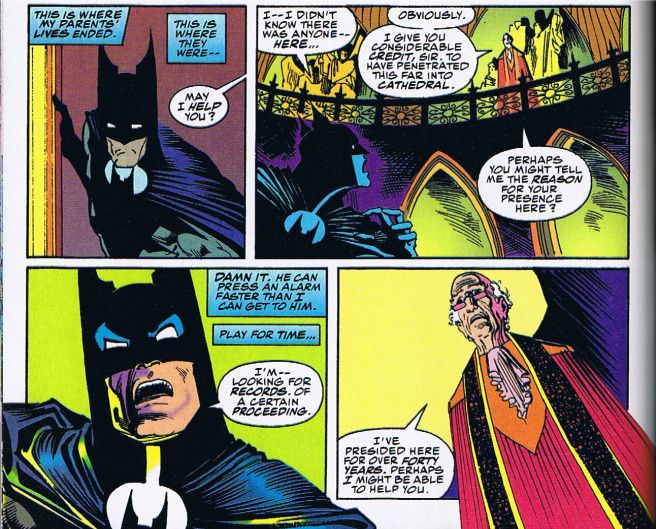

He soon discovers that the order came from the highest court in the land: the Star Chamber, located within the massive Gotham Towne Cathedral.

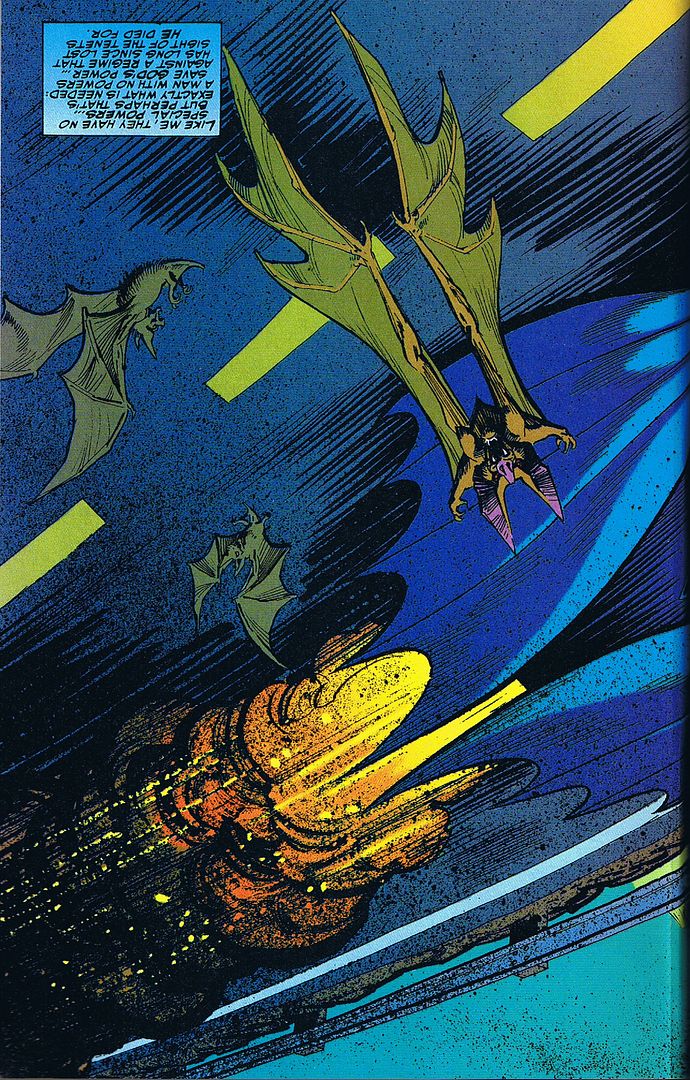

The costume, in keeping with the Golden Age origins, belonged to Dr. Thomas Wayne himself. In this world, the elder Wayne wore it when he played a demon in church Passion Plays. It's a nice touch, emphasizing the fearsome imagery of Batman for a man of God attacking a religious institution.

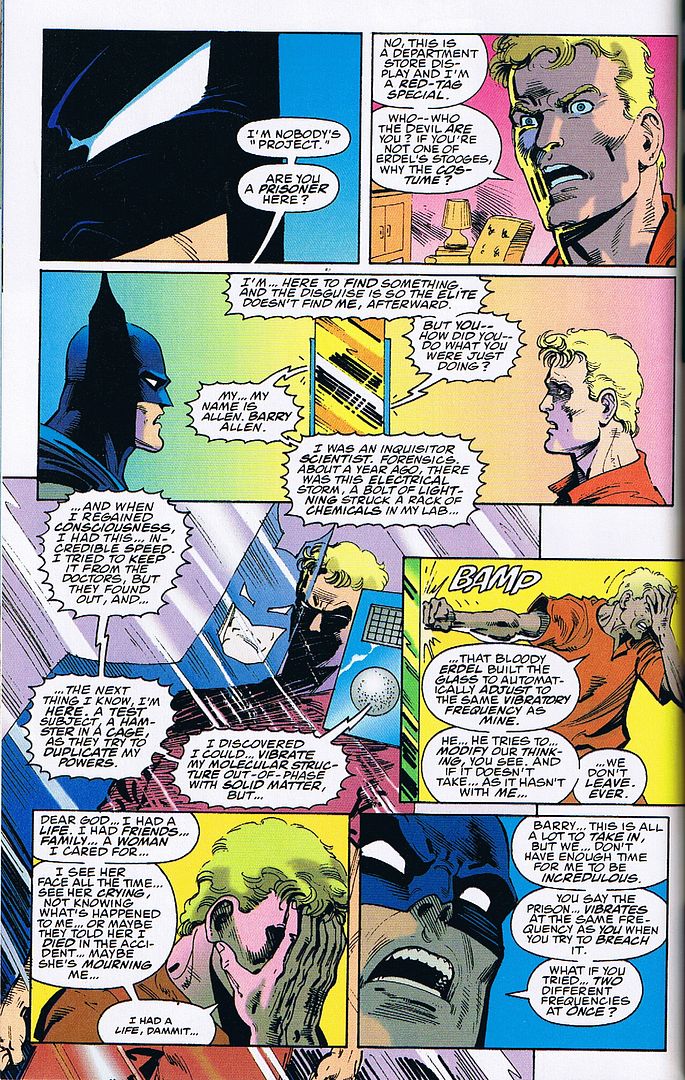

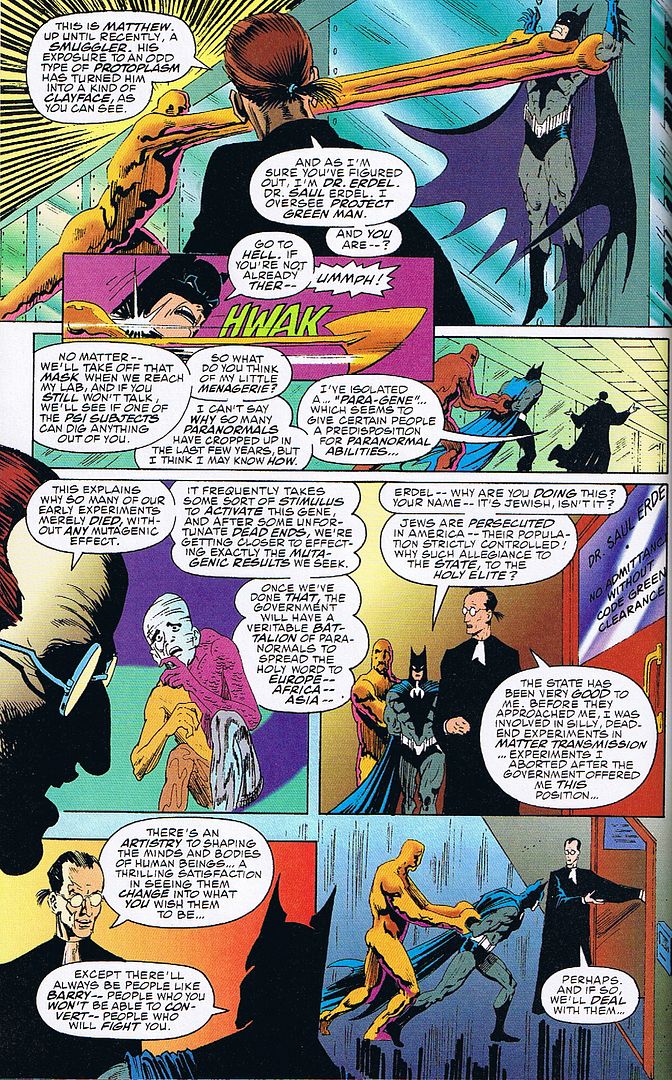

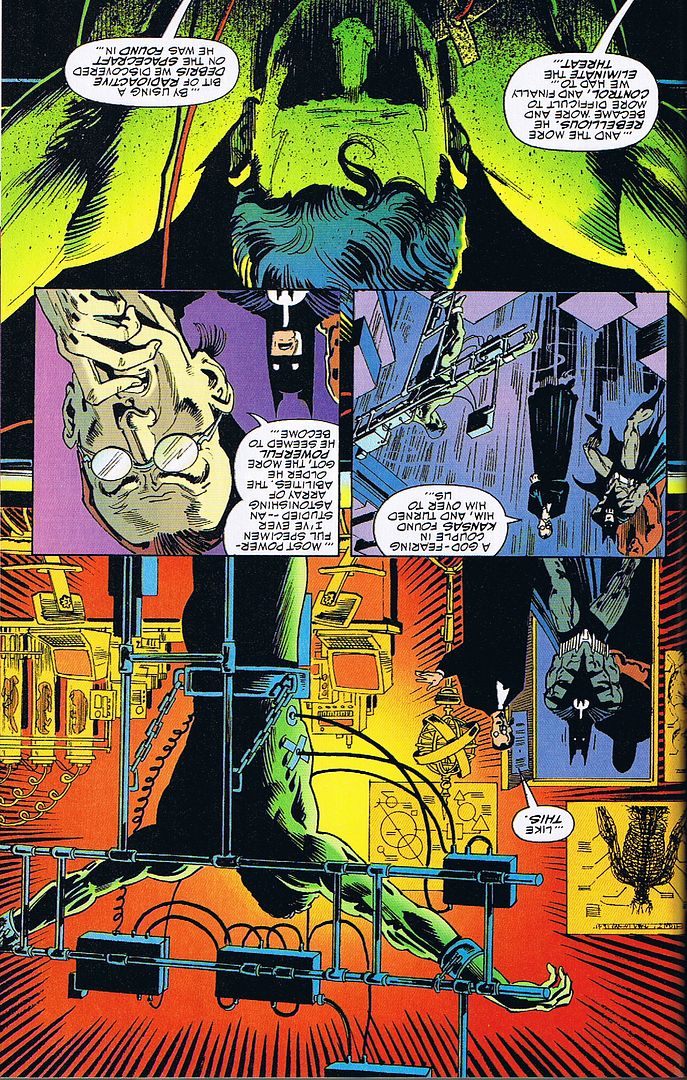

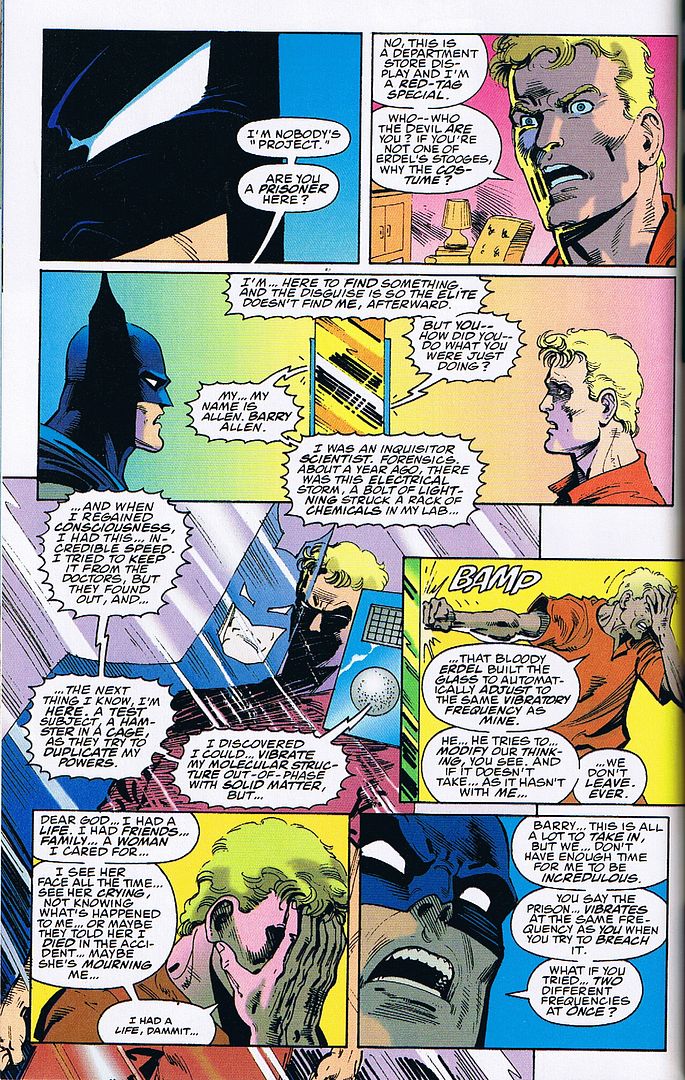

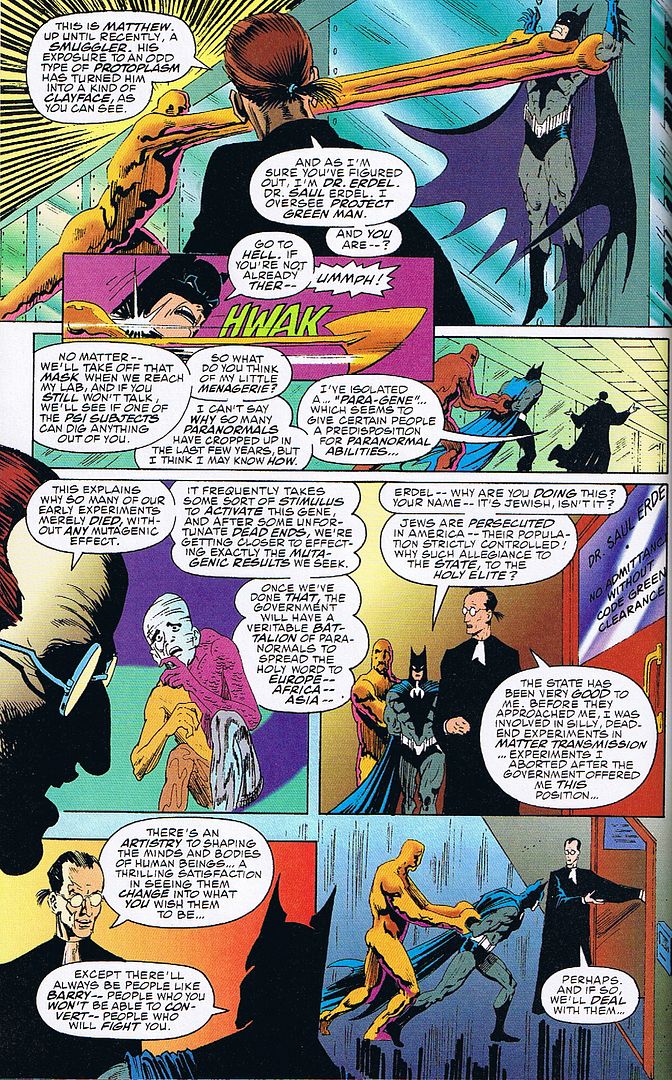

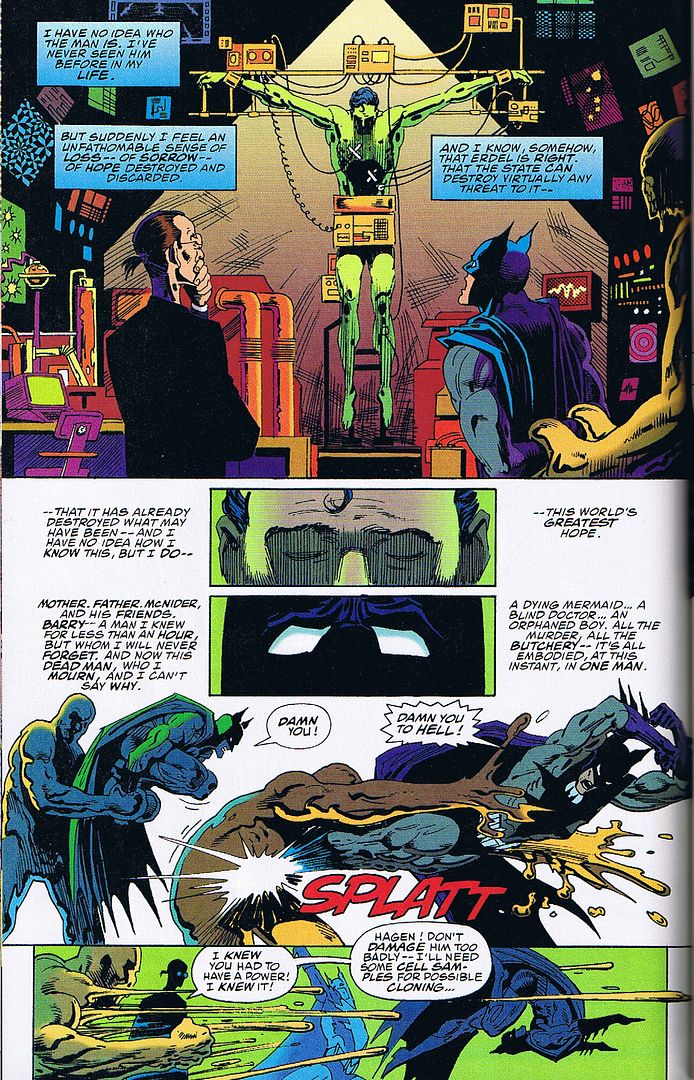

Down in the Detention Center, Batman discovers a prisoner of note, trying to vibrate his way out of his cell. He fails yet again, and then asks Batman, "Who are you? One of Erdel's new projects?"

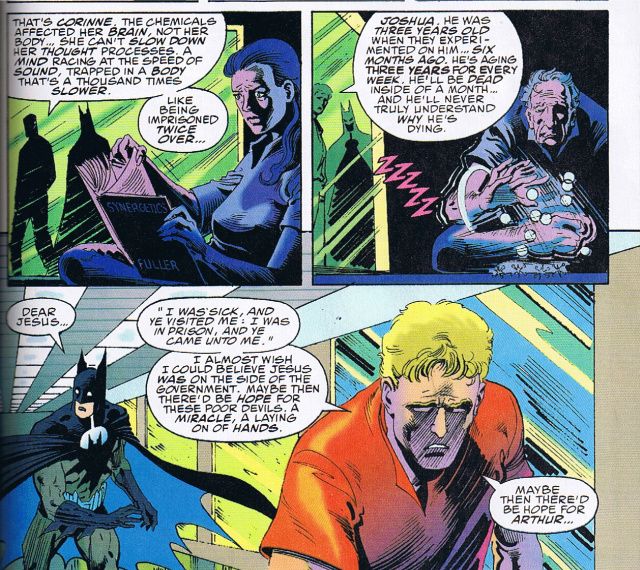

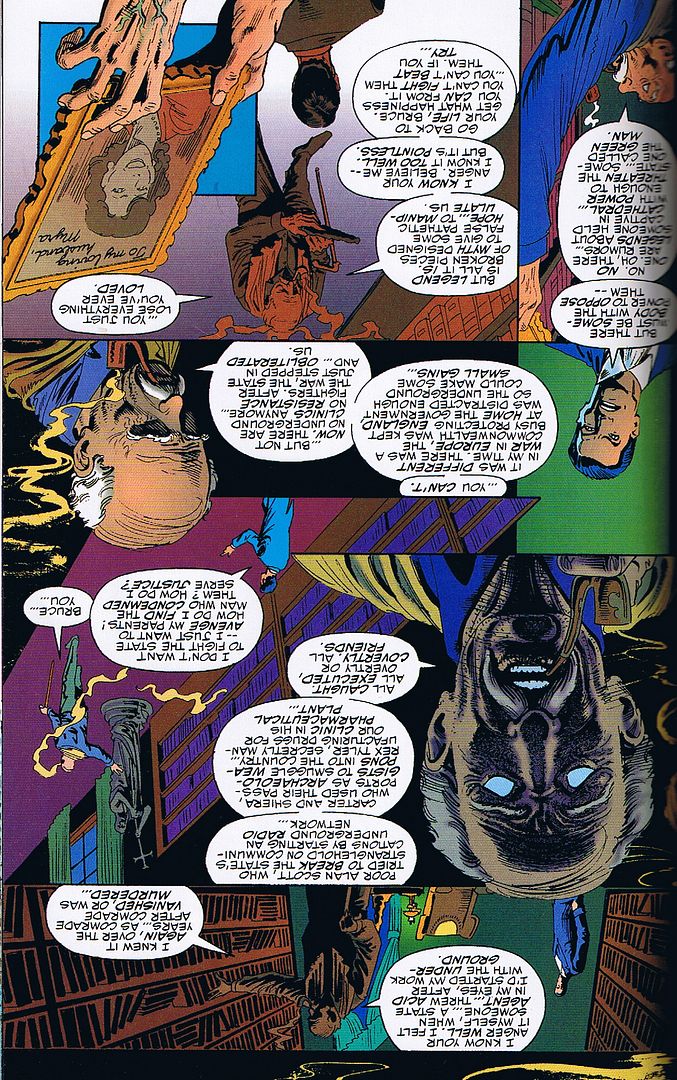

Erdel is another name which should ring a bell, and may also give you a clue as to what the "Green Man" is really about. Batman's suggestion works, and breaking free, Barry gives Batman a tour of Erdel's other "patients"...

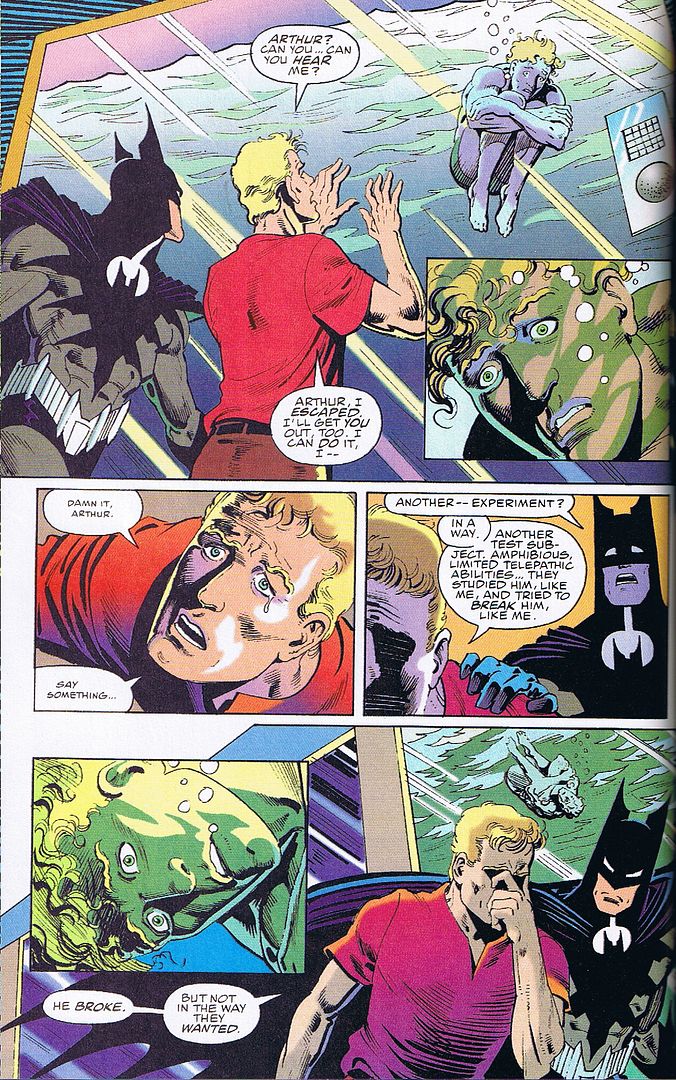

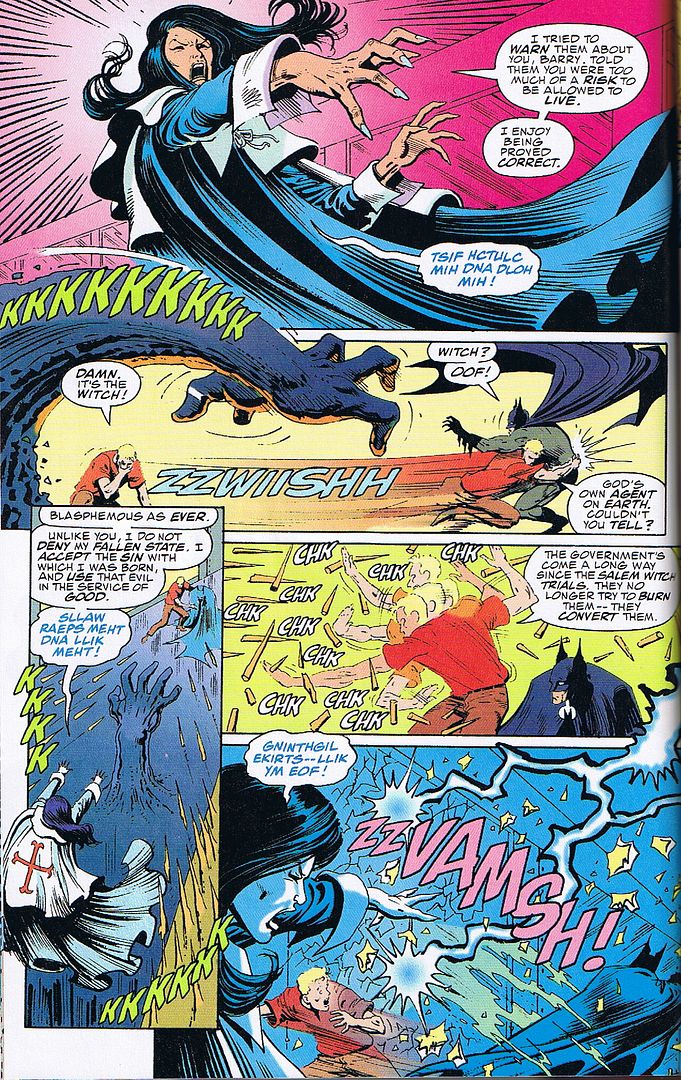

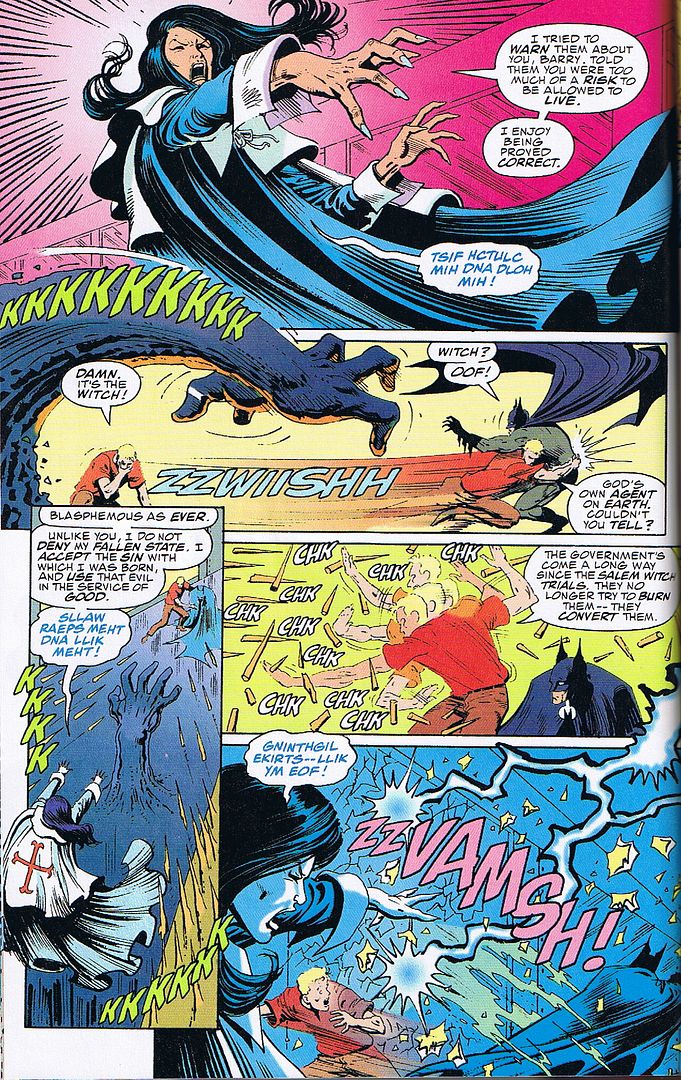

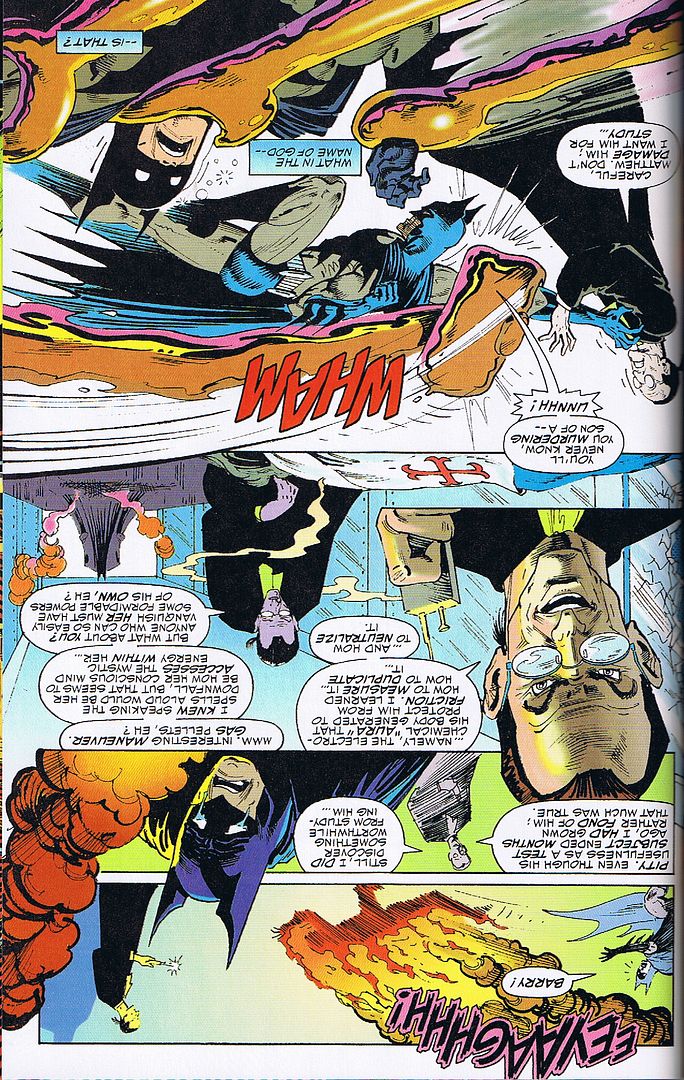

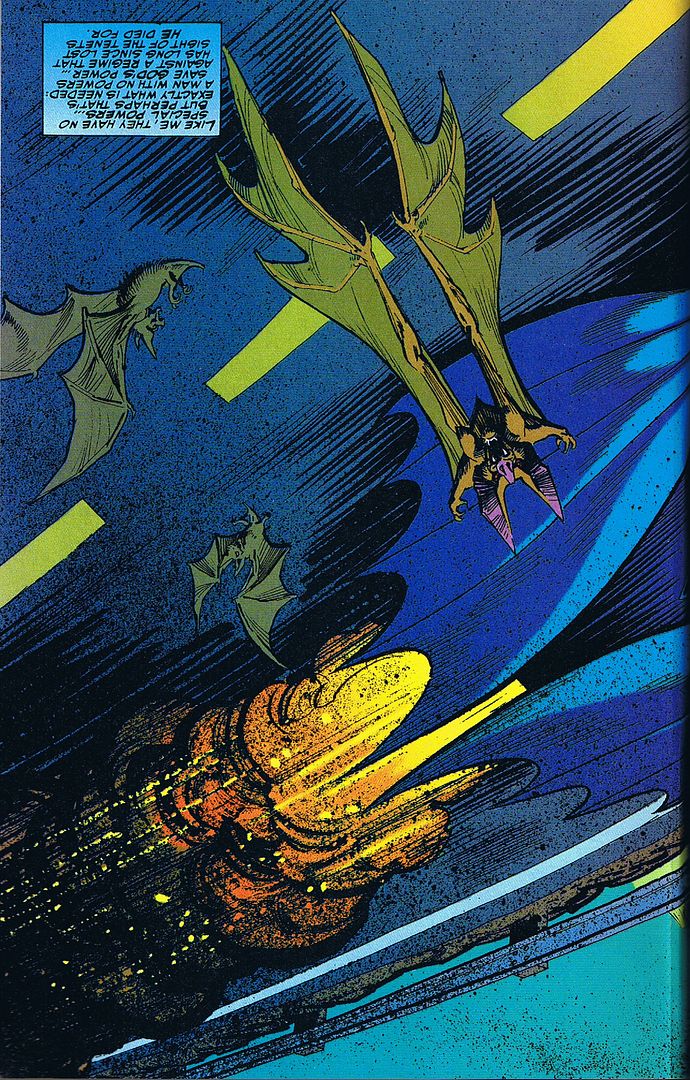

Barry explains that Aquaman was broken after many sessions of torture and experimentation. As Batman passes a series of lead-lined cells for the "irradiated" subjects, he and Barry are both suddenly attacked:

In the battle, one of the prisoners--a half-woman, half-fish creature, the result of a forced breeding between Aquaman and Lori Lemaris--is killed, whispering "free" with her dying words. It's a horrific, heartbreaking scene, and Zatanna revels in Barry's fury.

"Impious fool," she sneers. "To think I was once like you. Godless and profane. You become so much stronger when you stop resisting him..." (as the dialogue is in caps, it's unclear whether she's referring to God or Erdel) "... the power you feel is so liberating." Meanwhile, she virtually ignores Batman, considering the powerless man to be no threat.

As she's about to brainwash Barry with the words, "TSAC EDISA RUOY YSEREH DNA ECNATSISER... EKAT TSIRHC SA RUOY ROVIAS... DNA EHT ETATS SA RUOY--" she's interrupted by a gas pellet to the throat, courtesy of Batman.

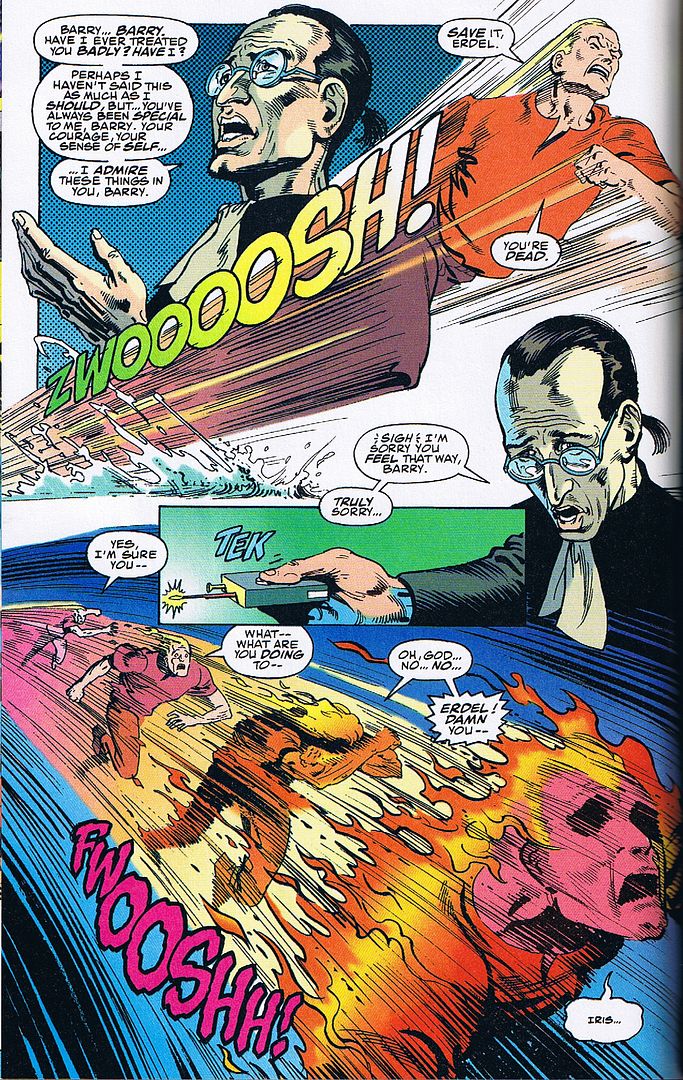

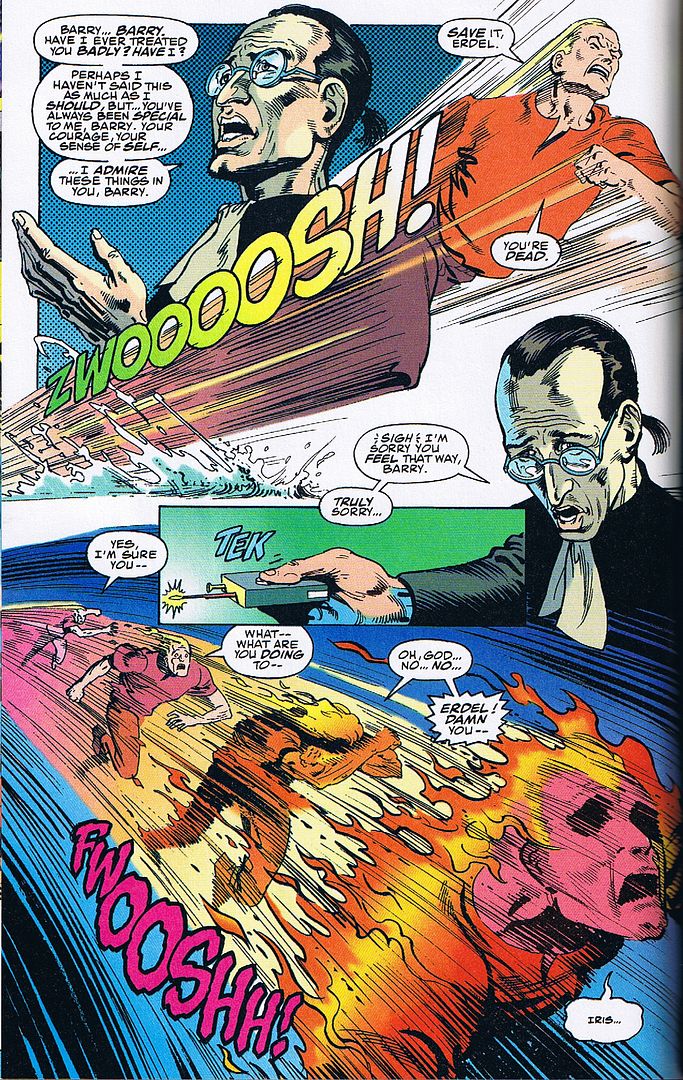

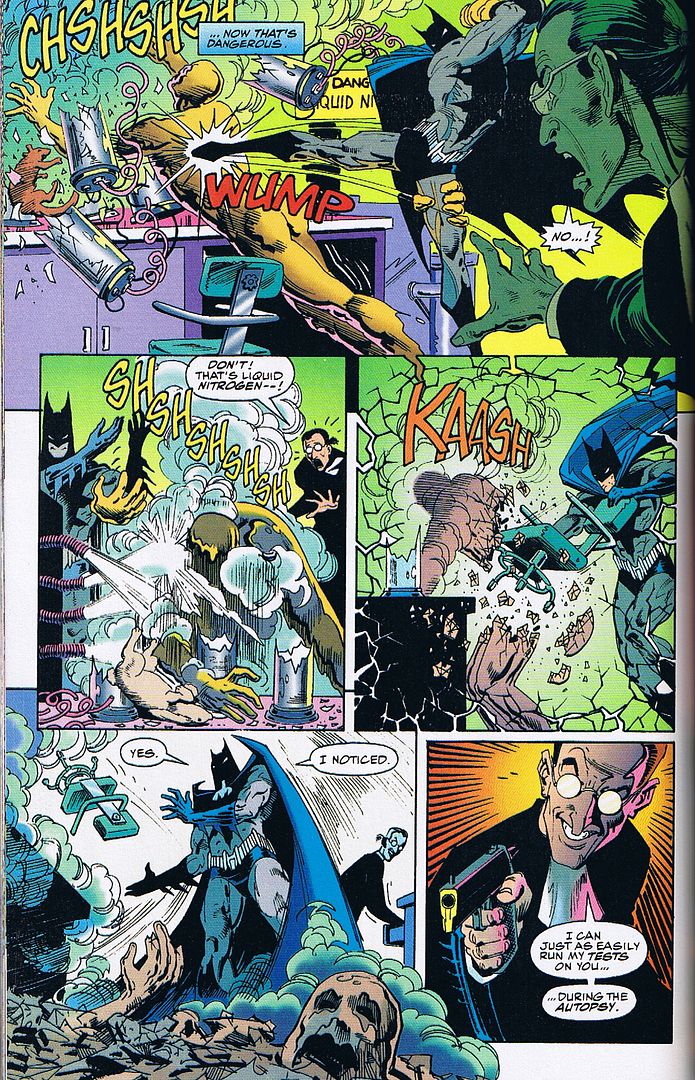

But just when the coast seems clear, that's when Dr. Erdel shows up (again, bearing zero resemblance to his comics counterpart; WTF, Breyfogle? He looks more like Jonathan Crane), asking Barry to return to his cell. At his breaking point, Barry refuses and vows to take revenge for every person Erdel has tortured, killed, and dissected.

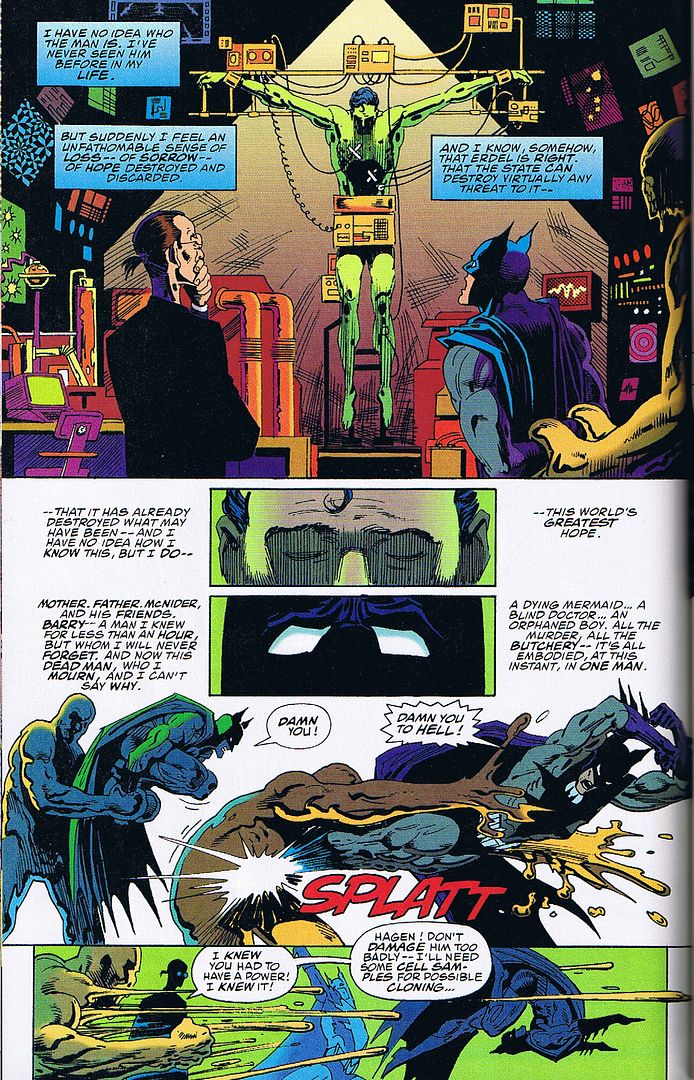

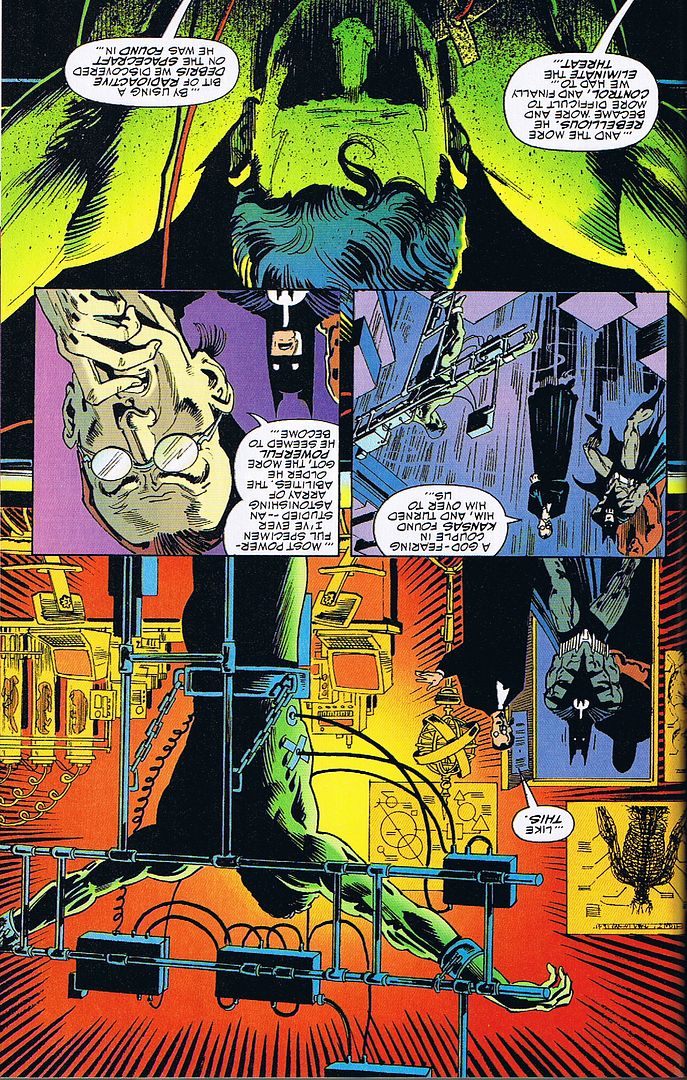

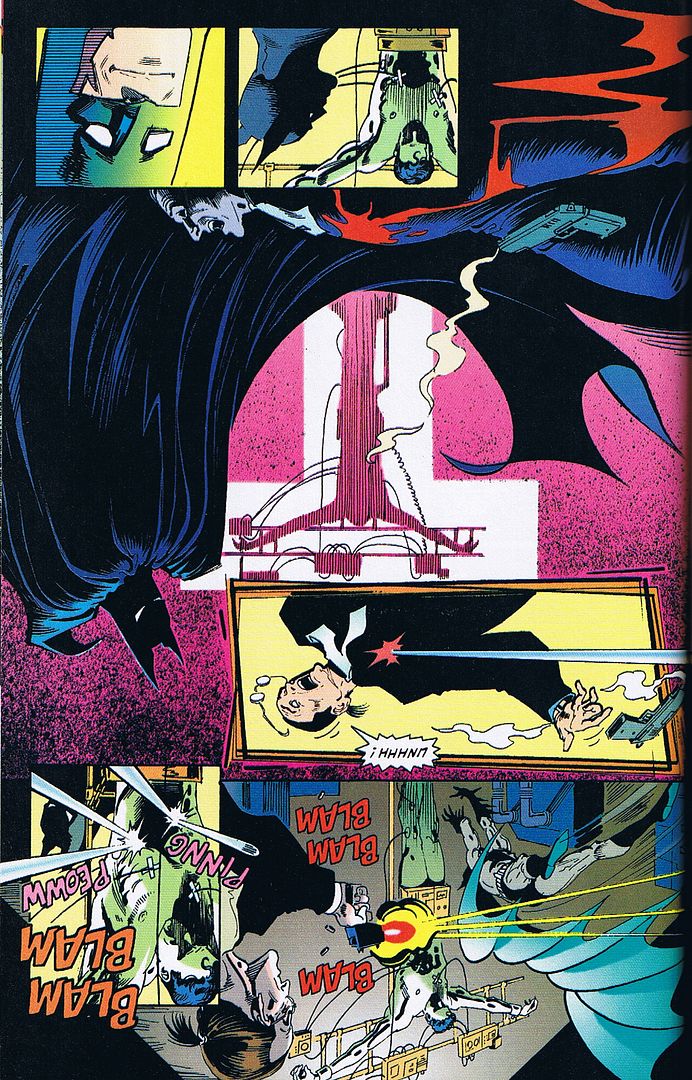

The idea of "Superman as Christ" is such a cliche by this point that its use here (even back in 1990) should induce eye-rolling. And maybe it did. For me, I find it incredibly powerful for a couple reasons. First, he's dead. Some people have read these pages and thought he was still alive and that Batman could free him, but no, the savior of humanity is dead, and if he's to be ressurected, we won't be seeing it in this universe.

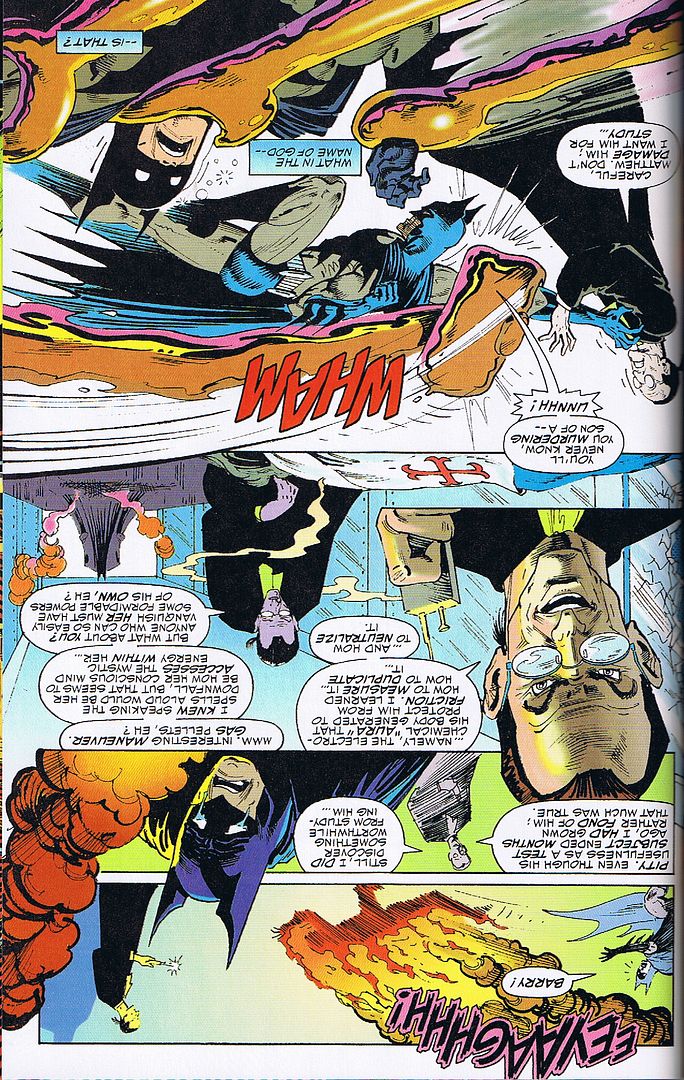

But even that would be cheap and meaningless without Bruce's reaction. No matter how dark this story gets, Brennert makes it a point to not just shock the reader with stuff like the above, but to acknowledge and mourn what was lost. What gives this story its soul is not in the images or ideas, but in how Bruce reacts: first with mourning, then with rage. And in that rage, both Erdel and Bruce suspect that maybe he is superpowered after all.

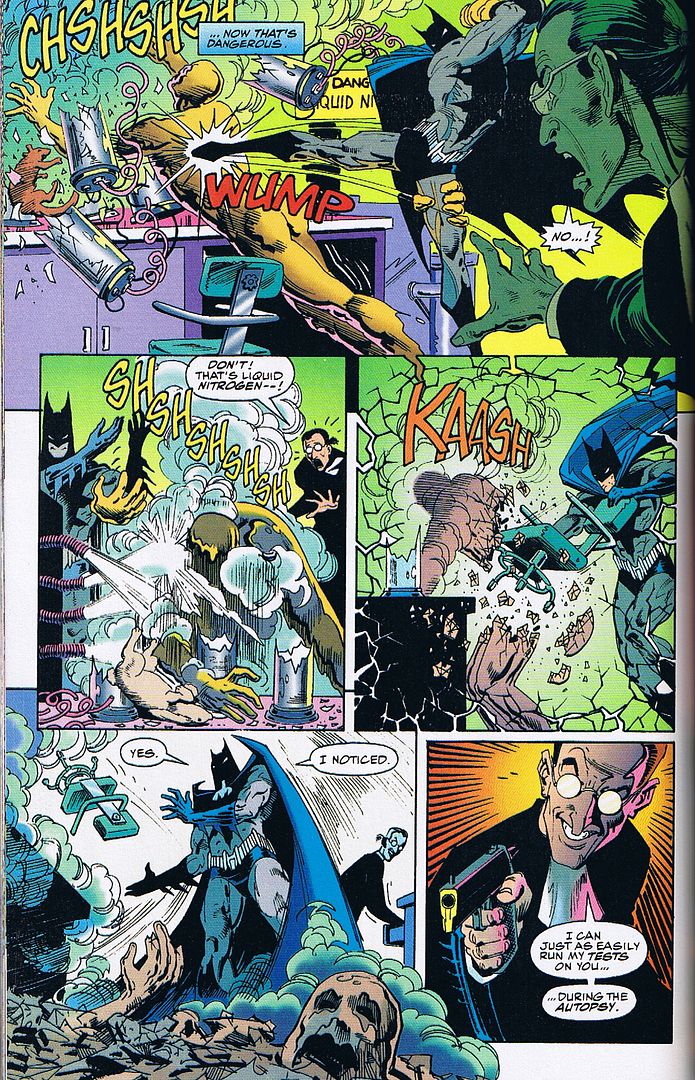

But in his battle with Clayface, Bruce realizes that all the rage in the world means nothing on its own. But rage combined with intellect and reason, however...

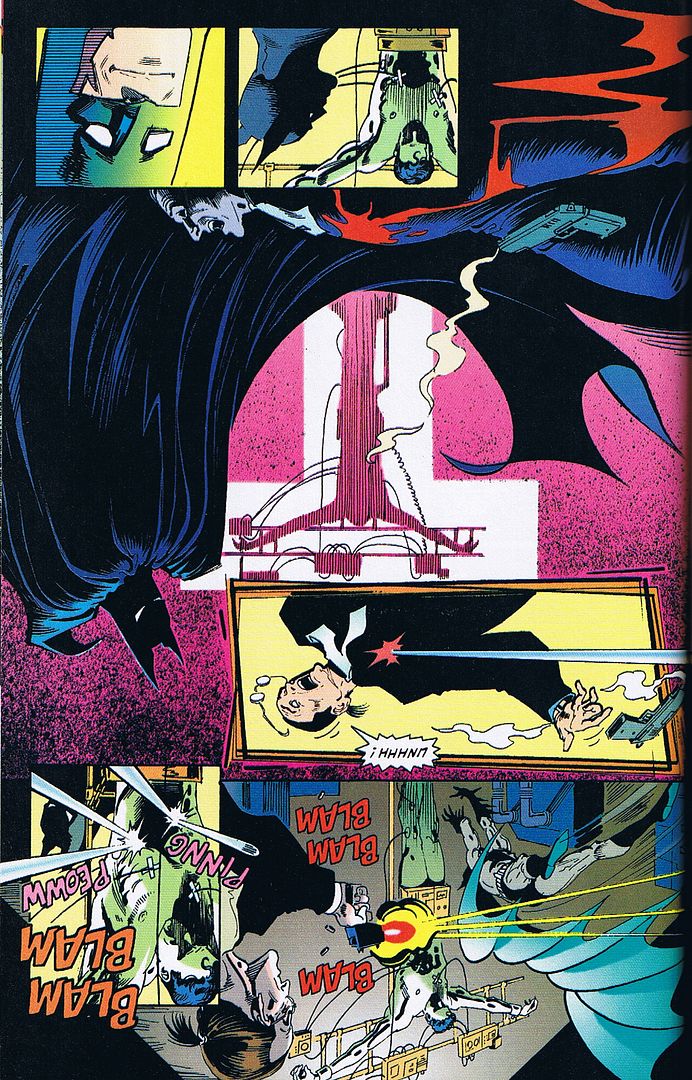

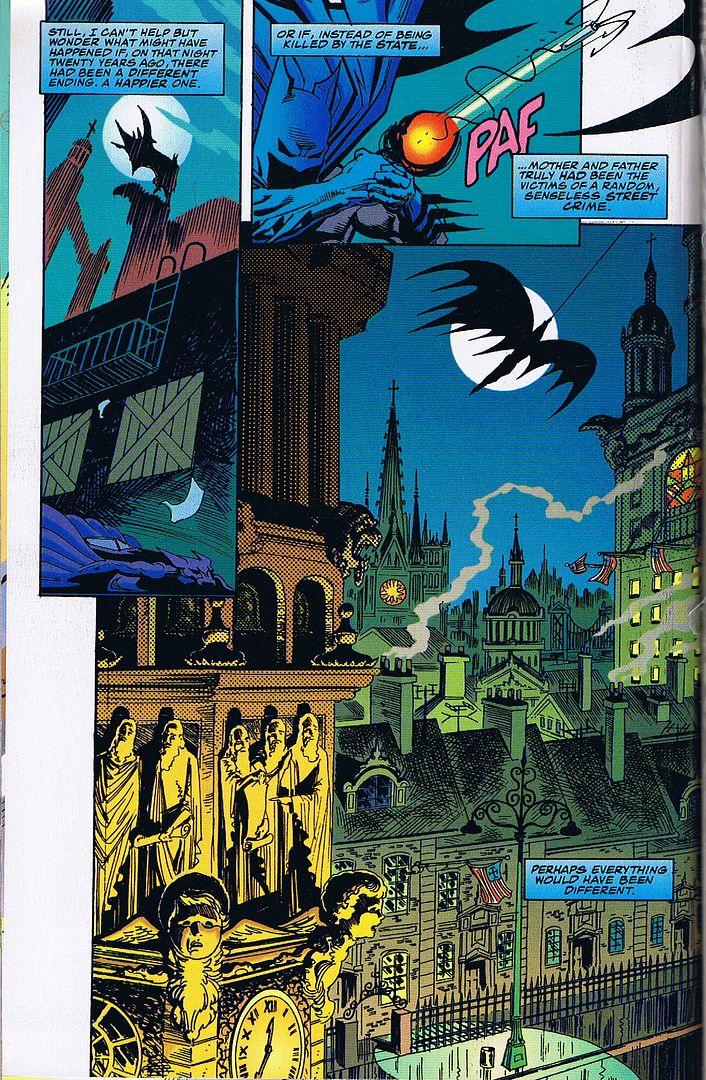

Again, the place where the bullet ricochets should induce eye-rolling, but I think Brennert pulls it off. YMMV.

This is another example of Brennert hinting at how the Puritans ended up embracing much of the iconography they abolished. This may explain the historical inaccuracy of the police being referred to as "Inquisitors," a term which would have been far too Catholic for the likes of the Puritans, or so I understand. I imagine you historians reading this have already been rolling your eyes at parts, so is there any room for this explanation to justify the mixed theocratic themes happening here?)

I'm reminded (why didn't I think of it sooner?!) of Frank Miller's aborted project Holy Terror, Batman!, which would have been about Batman versus Terrorism. I recall that Grant Morrison's once responded (and I'm paraphrasing here), "At that point, why not have 'Batman versus cancer?" That highlights the inherent ridiculousness of a character like Batman waging war against a faceless entity, especially a fictional character versus a real-life problem.

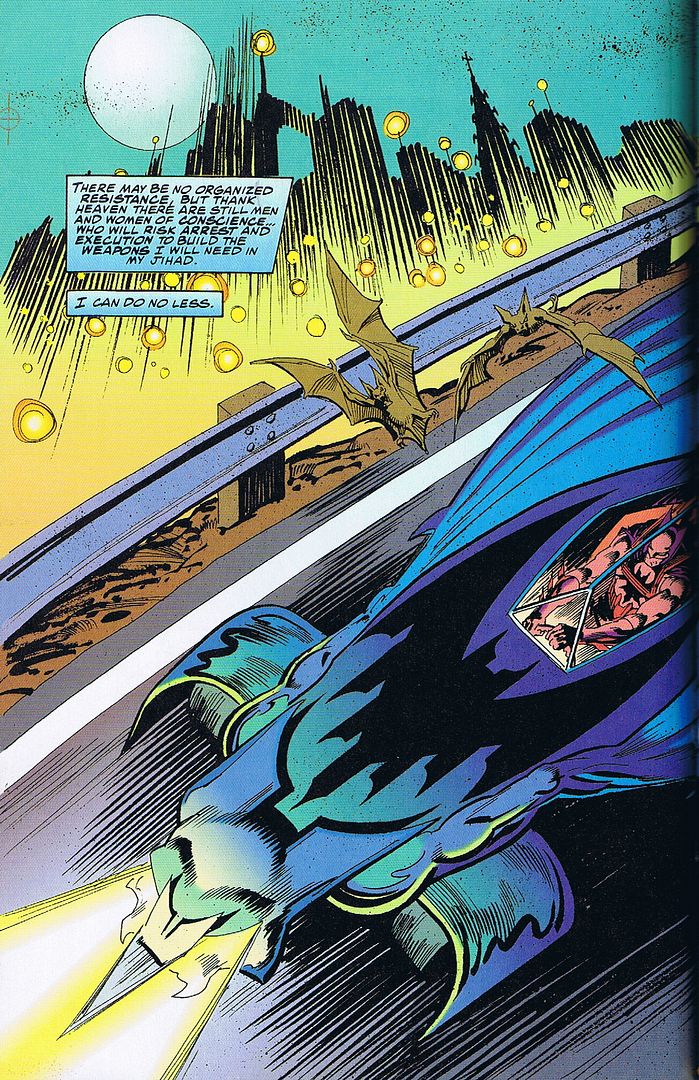

But what's remarkable is how that's what gives Brennert's story its power. The difference is, Batman himself is actually the terrorist here, waging his literal jihad against not against a single individual, or even a group, but the faceless state itself.

The implications here strike me as far more powerful than even Miller's own revolutionary Batman from The Dark Knight Returns/Strikes Again. Batman has essentially become the V of this dystopia.

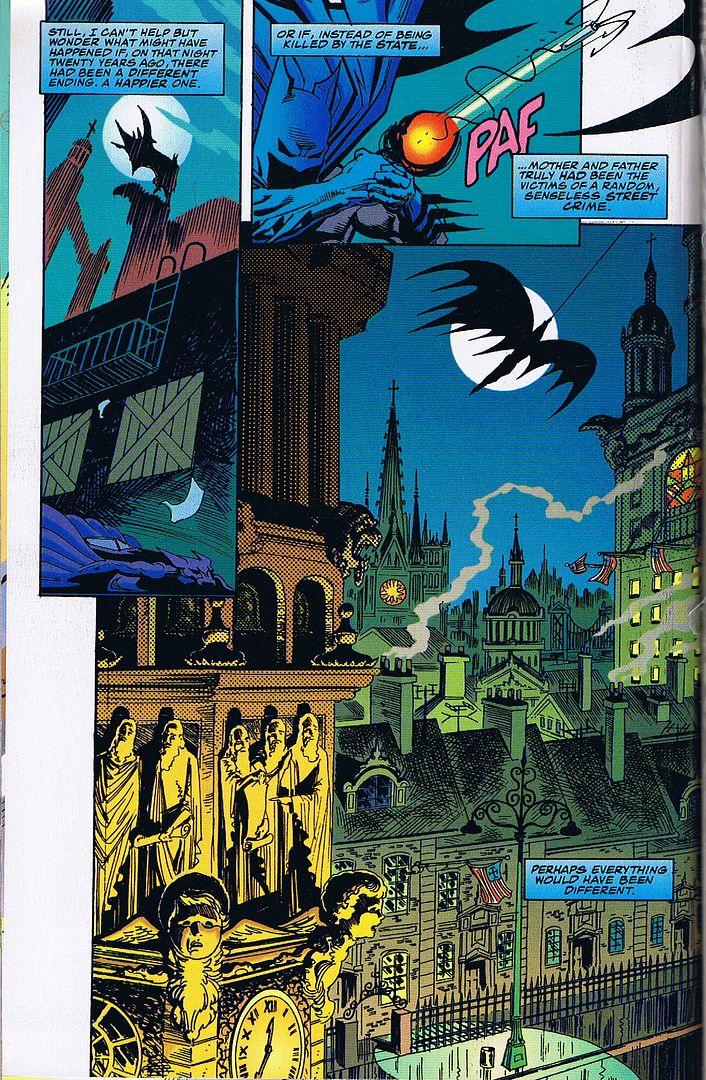

One last thing:

The implication, of course, is that Bruce is wrong in his supposition. If this Batman is engaged in a Holy War, it certainly puts our Batman's never-ending war on crime in a different light. Which is exactly what good Elseworlds can do.

Damn it, I want a sequel.

The best Elseworlds stories utilize the alternate reality format to gain fresh perspective on the characters and themes they represent. I've always loved the mantra which used to accompany the earliest books in this imprint:

"In Elseworlds, heroes are taken from their usual settings and put into strange times and places--some that have existed, and others that can't, couldn't, or shouldn't exist. The result is stories that make characters who are as familiar as yesterday seem as fresh as tomorrow."

I've always loved that last line. "As familiar as yesterday seem as fresh as tomorrow." So why are there so many mediocre Elseworlds stories? Why do so many follow the formula of "plug in X character in Y time setting, tell basically the same origin"? Asking "What If?" doesn't really matter if that question isn't followed by, "So What?"

That is not the case with Alan Brennert's last (and only) major DC story, Batman: Holy Terror, the first alternate universe DC story to carry the Elseworlds brand. It's that rare Elseworlds (hell, that rare story) which actually has something to say about its lead character and the alternate reality he inhabits.

In this instance, it's Batman in a Puritanical theocracy.

This story is not to be confused with a similarly-titled, aborted project by Frank Miller, although the two do play with similar ideas. Except Brennert's is far more subversive, even more so today than when it was published. After all, in this story, Batman is waging a Holy War. And what's another word for one of those?

From what page, you might gather that this story takes place a century or so in the past. But fast forward to the present day:

So yeah, in case you hadn't gathered, this a world where Oliver Cromwell lived on for another decade, thus leading to the Puritan Commonwealth staying in power in Britain and its colonies... including North America and, therefore, Gotham Towne.

I find it interesting how almost all of the names Brennert references are real people: Isaac Singer, Jorge Amado, and presumably Ollie North. This indicates a more direct parallel to our own real world rather that being strictly in the DCU, even with the mention of Ollie's sad fate. And really, even in an alternate universe, who really thinks that Oliver Queen repented? I sure as hell don't.

But where's Bruce in all this? We're introduced to the adult Bruce Wayne saying goodbye to Alfred, as Bruce is about to leave Wayne Manor to join the Priesthood. Bruce has actually found peace in this new path, having abandoned his old "dead-end" dream of being a gymnast. For nostalgia's sake, he practices a few moves in the gym, and an outside voice remarks, "Lost none of your form, I see."

In Gordon's defense, Brennert wrote a whole scene with a magistrate insinuating threats against Gordon's family if he perused the Chill investigation. Also, another neat little touch: Gordon was then newly transferred in from "New Amsterdam."

If you're a DC fan, the name Dr. Charles McNider, may ring a bell...

I don't know a ton about Cromwell's history, but from what little I know, is there any indication that Brennert was being ironic in having McNider refer to Cromwell's church as "tolerant" and "kind"? If so, it adds a subtle layer of complexity to why Bruce doesn't end up abandoning his faith itself.

This story could easily have been about Bruce experiencing a loss of faith, and waging his war against the Theocracy in the name of secularism and reason, but it doesn't go that route. We see that right away on the day of Bruce's confirmation:

The Bishop, by the way, is none other than Judson Caspian, AKA the Reaper from Batman: Year Two, although the art bears no resemblance to the same character. We actually learn his name when we see Bruce hacking into Bishop Caspian's PC, which twinges at Bruce's conscience. He genuinely dislikes betraying the confidence of a "good man, an honorable man," but he has to find out who ordered his parents' execution.

He soon discovers that the order came from the highest court in the land: the Star Chamber, located within the massive Gotham Towne Cathedral.

The costume, in keeping with the Golden Age origins, belonged to Dr. Thomas Wayne himself. In this world, the elder Wayne wore it when he played a demon in church Passion Plays. It's a nice touch, emphasizing the fearsome imagery of Batman for a man of God attacking a religious institution.

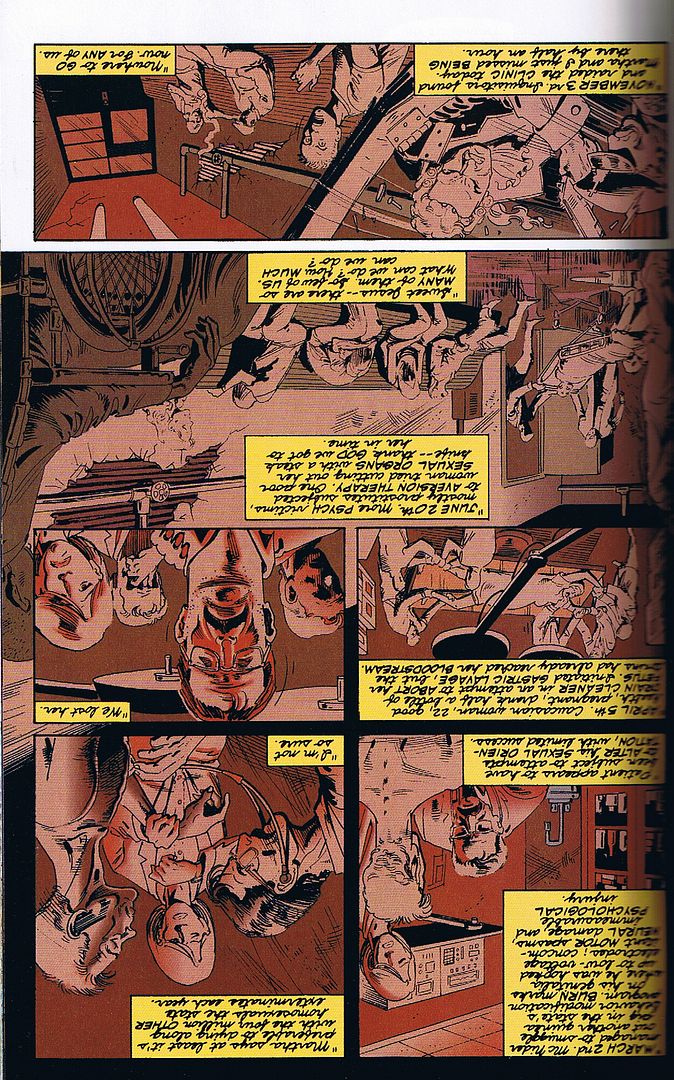

Down in the Detention Center, Batman discovers a prisoner of note, trying to vibrate his way out of his cell. He fails yet again, and then asks Batman, "Who are you? One of Erdel's new projects?"

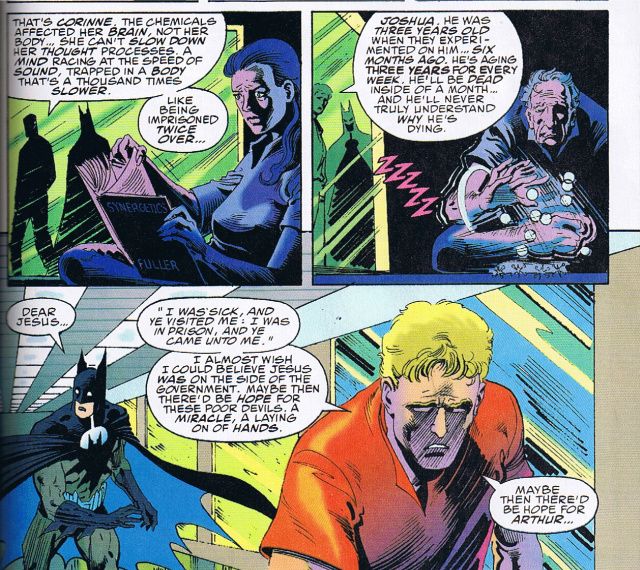

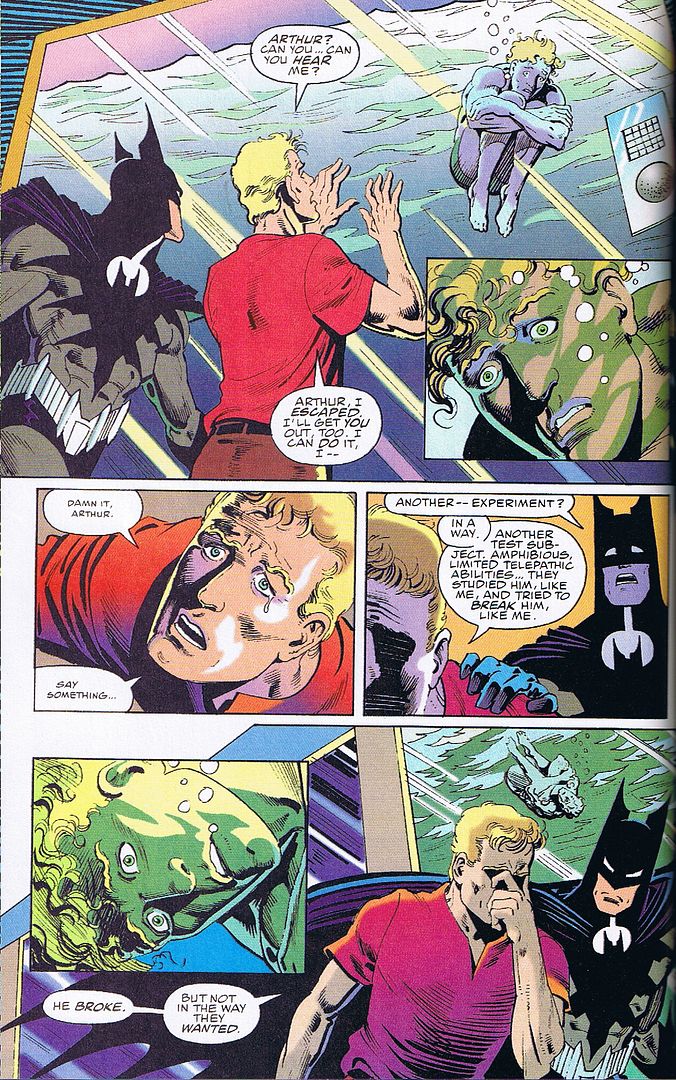

Erdel is another name which should ring a bell, and may also give you a clue as to what the "Green Man" is really about. Batman's suggestion works, and breaking free, Barry gives Batman a tour of Erdel's other "patients"...

Barry explains that Aquaman was broken after many sessions of torture and experimentation. As Batman passes a series of lead-lined cells for the "irradiated" subjects, he and Barry are both suddenly attacked:

In the battle, one of the prisoners--a half-woman, half-fish creature, the result of a forced breeding between Aquaman and Lori Lemaris--is killed, whispering "free" with her dying words. It's a horrific, heartbreaking scene, and Zatanna revels in Barry's fury.

"Impious fool," she sneers. "To think I was once like you. Godless and profane. You become so much stronger when you stop resisting him..." (as the dialogue is in caps, it's unclear whether she's referring to God or Erdel) "... the power you feel is so liberating." Meanwhile, she virtually ignores Batman, considering the powerless man to be no threat.

As she's about to brainwash Barry with the words, "TSAC EDISA RUOY YSEREH DNA ECNATSISER... EKAT TSIRHC SA RUOY ROVIAS... DNA EHT ETATS SA RUOY--" she's interrupted by a gas pellet to the throat, courtesy of Batman.

But just when the coast seems clear, that's when Dr. Erdel shows up (again, bearing zero resemblance to his comics counterpart; WTF, Breyfogle? He looks more like Jonathan Crane), asking Barry to return to his cell. At his breaking point, Barry refuses and vows to take revenge for every person Erdel has tortured, killed, and dissected.

The idea of "Superman as Christ" is such a cliche by this point that its use here (even back in 1990) should induce eye-rolling. And maybe it did. For me, I find it incredibly powerful for a couple reasons. First, he's dead. Some people have read these pages and thought he was still alive and that Batman could free him, but no, the savior of humanity is dead, and if he's to be ressurected, we won't be seeing it in this universe.

But even that would be cheap and meaningless without Bruce's reaction. No matter how dark this story gets, Brennert makes it a point to not just shock the reader with stuff like the above, but to acknowledge and mourn what was lost. What gives this story its soul is not in the images or ideas, but in how Bruce reacts: first with mourning, then with rage. And in that rage, both Erdel and Bruce suspect that maybe he is superpowered after all.

But in his battle with Clayface, Bruce realizes that all the rage in the world means nothing on its own. But rage combined with intellect and reason, however...

Again, the place where the bullet ricochets should induce eye-rolling, but I think Brennert pulls it off. YMMV.

This is another example of Brennert hinting at how the Puritans ended up embracing much of the iconography they abolished. This may explain the historical inaccuracy of the police being referred to as "Inquisitors," a term which would have been far too Catholic for the likes of the Puritans, or so I understand. I imagine you historians reading this have already been rolling your eyes at parts, so is there any room for this explanation to justify the mixed theocratic themes happening here?)

I'm reminded (why didn't I think of it sooner?!) of Frank Miller's aborted project Holy Terror, Batman!, which would have been about Batman versus Terrorism. I recall that Grant Morrison's once responded (and I'm paraphrasing here), "At that point, why not have 'Batman versus cancer?" That highlights the inherent ridiculousness of a character like Batman waging war against a faceless entity, especially a fictional character versus a real-life problem.

But what's remarkable is how that's what gives Brennert's story its power. The difference is, Batman himself is actually the terrorist here, waging his literal jihad against not against a single individual, or even a group, but the faceless state itself.

The implications here strike me as far more powerful than even Miller's own revolutionary Batman from The Dark Knight Returns/Strikes Again. Batman has essentially become the V of this dystopia.

One last thing:

The implication, of course, is that Bruce is wrong in his supposition. If this Batman is engaged in a Holy War, it certainly puts our Batman's never-ending war on crime in a different light. Which is exactly what good Elseworlds can do.

Damn it, I want a sequel.