Letters by Henry Miller to Hoki Tokuda Miller

In 1966, Henry Miller was calling The Pacific Palisades home. On Wednesday nights, he'd go into Beverly Hills to visit his doctor and friend, Lee Siegel. He never brought along any "intellectuals," as he was "sick of hearing people discuss art and literature in [his] home;" it was a chance for him to have some fun.

On one of these nights, in Beverly Hills, Miller met a new love. Her name was Hoki Tokuda, and she was in the United States working at the-now extinct-- Imperial Gardens. She was, by all accounts, an accomplished jazz singer and pianist. She was on a work visa. She'd also been in two films, by then. Japanese films, they were titled Nippon Paradise(1964) and Chinkoro Amakko (1965). (Those are IMDb links you're looking at, incidentally, and neither offers much to look at.)

She was twenty-seven years old.

Dated February 22nd, this is the first note from Miller to his newfound love in the collection of their correspondence, edited by Joyce Howard:

Dear Hoki

I hope to see you one evening this week at the Imperial Gardens. Maybe I will bring my friend Joe Gray along. He wants to meet nice Japanese girl.

Henry Miller

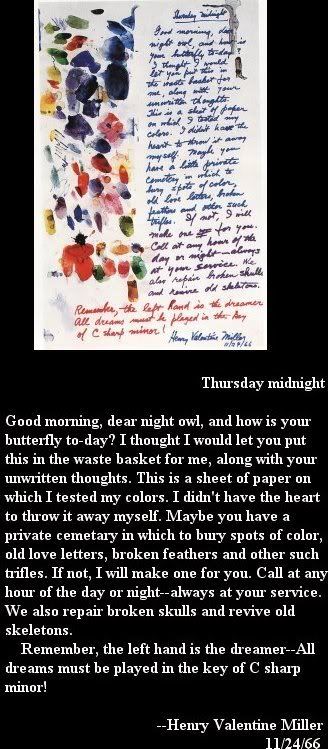

(This needs to be viewed at full-screen. Please let me know if there are any problems viewing this. Thanks, in advance!)

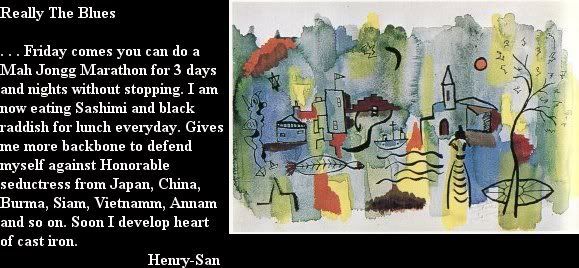

The following month, he sent her a few short notes, usually just to say that he was thinking about her, or planning on a visit. You get the sense, reading them, that's there's a lot going on off the page. He wishes her luck finding a house. He tries peppering his correspondence with Japanese words, and he signs one of these little notes "Henry-San" (which, if my source is right, you're not supposed to do). Throughout the volume, he addresses her as "Hoki-san." But he's just warming up. In April, he sends her a series of postcard-sized watercolors, one the backs of which is one, continuous message.

Hiroshiga-Probably Ando Hiroshige?

Hokusai -No doubt he's referring to Katsushika Hokusai

Both men were Ukiyo-e woodblock artists from the Edo period.

Wu2 Wei4 is, briefly, an important tenet from Taoist thought which-literally-means "without action." The theme of surrender is an important one running through Miller's work. Take the first passage from Tropic of Capricorn, for instance:

"Once you have given up the ghost, everything follows with dead certainty, even in the midst of chaos. From the beginning it was never anything but chaos; it was a fluid which enveloped me, which I breathed in through the gills. In the subtrata, where the moon shone steady and opaque, it was smooth and fecundating above it was a jungle and a discord. In everything, I quickly saw the opposite, the contradiction, and between the real and the unreal the irony, the paradox. I was my own worst enemy. There was nothing I wished to do which I could just as well not do. Even as a child, when I lacked for nothing, I wanted to die; I wanted to surrender because I saw no sense in struggling. I felt that nothing would be proved, substantiated, added or subtracted by continuing an existence which I had not asked for. everybody around me was a failure, or if not a failure, ridiculous. Especially the successful ones. The successful ones bored me to tears. I was sympathetic to faults, but it was not sympathy that made me so. It was a purely negative quality, a weakness which blossomed at the mere sight of human misery. I never helped anyone expecting that it would do any good; I helped because I was helpless to do otherwise. To want to change the condition of affairs seemed futile to me; nothing would be altered, I was convinced, except by a change of heart, and who could change the hearts of men? Now and then a friend was converted; it was something to make me puke. I had no more need of God than He had of me, and if there were one, I often said to myself, I would meet Him calmly and spit in His face."

The Chinese characters in the upper right-hand corner read: "Nian2 Nei4 Qing1 Shu4" which means, roughly "Settle your accounts within a year."

"Dostoievsky" is Miller's preferred transliteration of Fyodor Dostoevsky's name. Dostoevsky could arguably be called the granddaddy of 20th Century Literature. I've seen his name in Miller's books so many times, now, that I've lost count. It's even there in Moloch!

This is from Nexus:

"Myself, I have never pretended to understand Dostoevski. Not all of him, at any rate. (I know him, as one knows a kindred soul.) Nor have I read all of him, even to this day. It has always been my thought to leave the last few morsels for deathbed reading. I am not sure, for instance, whether I read his Dream of the Ridiculous Man or heard tell about it. Neither am I at all certain that I know who Marcion was, or what Marcionism is. There are many things about Dostoevski, as about life itself, which I am content to leave a mystery. I like to think of Doestoevski as one surrounded by an impenetrable aura of mystery."

More about J.P. Babcock can be found

here. (This is from a site covering a mah jong controversy.)

Russ Tamblyn is the psychiatrist from Twin Peaks. His first role was in The Boy with Green Hair. Tamblyn was probably working on War of the Gargantuas, while in Japan.

Pierre Loti--Louis Marie Julien Viaud, a French writer who was very fond of writing about his travels in a semi-autobiographical style. . . A soul kindred to Miller's, perhaps.

Prof. Ito-Oddly enough, there was a Prof. Ito who came to the U.S. in 1907 and opened a kodokanjudodojo. I'm guessing this probably wasn't him, the wrestler Miller saw, but one can always hope.

"Deux Jeunes Filles" is French, and it means "Two young girls." You might recognize it from the cover of the posthumous collection Into The Heart of Life.

After that, things get pretty dull. He keeps telling her she looks beautiful, that she appears more beautiful with each time he sets eyes on her. He sends her records, gives her articles and pictures clipped from magazines. A line from a letter, dated July 12th, 1966, pretty much sums up the tone of the letters in this period of their lives:

"This doesn't make much sense, does it? It's just an excuse to say a few words to you."

If you hear the sour note of unrequited love in that measure, your ear is attuned to Miller's prose. The entire volume stands as a testament to Miller's. . . unique choice in unresponsive women. "I would love to fall in love with you," he writes. "But I know that you are only in love with the love."

He tries and tires, though. Aside from the references to Japanese culture he makes, he attempts to write to her in Japanese. Romanized Japanese, to be sure. "If only I could write to you in Japanese! What things we could tell each other!"

The language gap comes up quite a bit, actually. There are times when I wonder if he held on to the idea of her not understanding him as a means of sustaining interest in (or holding on to some hope for) her. He tries his best to encourage her to write. Take this, from July 17th, 1966:

"In page one of your letter I was struck by a phrase you used-"I feel that I have recovered my heart!" (listening to Ravel). This is beautiful. No English writer would have said it just this way. It is correct but most unusual. Yours is better than anything "we" might say."

Yet, throughout the entire book, his most consistent gripe after her not expressing herself in conversation is his lack of letters from her.

Still, he kept on.

By the time August rolls around, he starts sending her longer letters. They get slightly less tedious. He starts to "slip away," as we writes, and the content of the letters gets better as a result. When he lets go of the idea of capturing her love, his mind is free to be itself, and his writing becomes enjoyable. His writing, I think, becomes automatic when he let's go of what he "wants" and allows his hand to work its magic.

Nevertheless, that doesn't last for too long. On August 24th, he wrote her a letter containing this (kind of scary) demand:

"I want you to come here in the afternoon, have a swim, go to dinner with me and spend the whole evening with me. You owe me such an evening, And if you really love me you will do it. I love you more and more each time I see you."

Apparently, she went through with it. He writes her:

"If I gave you a sleepless night, and myself as well, it was because it was one of the very rare times in my life that I had to sleep beside a woman without touching her. When dawn came I was at least able to gaze at your countenance. What a world to study, to explore, in your night face! An entirely different face than Hoki wears in her waking moments. The face of a stranger, carved out of lava, like some oceanic goddess. More mysterious with eyes closed and features sculpted out of ancestral memories. An almost barbaric look, as if you had been resurrected from some ancient city-like Ankor Wat-or the submerged ruins of Atlantis. You were ageless, lost not in sleep but in the myth of time. I shall always remember this face of sleep long after I get to know the hundred and one faces you present the world. It will be the dream face which you yourself have never seen and which I will guard as the sacred link between the ever-changing Hoki and the ever-searching Henry-San. This is my treasure and my solace. "

The last bit could easily have been picked from any of the lines stricken from his descriptions of June Mansfield in Crazy Cock, Tropic of Capricorn, or The Rosy Crucifixion. Not only does the woman in question, typically, ignore him (or, so he feels), but she always has a large cache of "masks" at hand for different social settings. . . and it's only Miller that sees the true Hoki.

It sounds a little bit like projection, to me. Not that I want to get into that, now, but if the subject of psychological troubles creeps into this, it's probably because Miller saw it much the same light (from November, 25th, 1966):

"I hope I have the courage to mail this letter and not put it away in a drawer, as I have with the others I wrote you. For with this goes the last ounce of pride I possess. I have to know, I must know, whether you really love me or not. I have been in absolute torture for months now. I can't hold out much longer. I am truly at the end of my rope. I can't work, I can't sleep; my mind is on you perpetually, without let up. It's not a sickness any more, it's a mania. I am obsessed and possessed."

And this is in the first third of the book! The one entitled "Falling in Love!"

(Note the bit about not sending her all the letters he's written. Joyce Howard, the editor, made no attempt to distinguish which of the letters Tokuda had actually received during her relationship with Miller. It's left to us to try and figure that out, I guess. You might wonder what Miller himself thought of some of his more vituperative turns of phrase, on the morning after.)

It only gets sadder, many letters begin with the threat that "this is the last one." Of course, the substance of his correspondence kind of modulates between despairing and rejoicing, but after the letter from the twenty-fifth of November, it never ceases to be pathetic.

Based on the letters from 1967, the Japanese tabloids got a hold of the story and ran wild with it. Included in this volume is a couple of letters Miller sent to a man named Kawabata Atsu. Atsu lived in Japan and, I suppose, had some contacts or wielded some influence within Japan's society of letters. Miller wrote him in an attempt to "set the record straight." He also, in a Quixotic flourish, sent him a letter addressed to "The Japanese Reading Public."

There's some widespread speculation that Tokuda went after Miller for the Green Card, but occasional remarks Miller makes about the Japanese press, might lead one to consider whether or not her relationship with him did a lot to increase her marketability back home in Japan.

Unfortunately, we're not privy to the rumors and scandals that occupied idle Japanese, at the time. However, there is one touching letter in the bunch, from Miller to Hoki Tokuda's father. Though not necessarily on the subject of Hoki's place in the Japanese media.

Miller had been invited to Japan on a few occasions, but Hoki herself, and her family. He'd refused all invitations, which is a little sad to think about. He really was getting old. He was probably older than Mr. Tokuda, himself. This is a paragraph from his letter, dated August 18th, 1967:

"But now let me try to explain myself to you, if I can. The older I get the more I struggle not to make plans in advance, not to think of tomorrow, or yesterday, either, for that matter. I try my best to live day to day, as we say in English. This is a result of my philosophical strain rather than of my innate temperament. I have been all my life a most active man, perhaps too much so. All I ever wanted of life was the freedom to write what I had to express and to do so with perfect freedom. It has been a long hard struggle, and I suppose one might say that I won out. But at what a price! As a result of a my achievement, my fame or success, whatever you wish to call it, the word tries to involve me in things which no longer concern me. Every day of my life, for the last ten years or more, I have to struggle to win a couple of hours which I my truly call my own. The consequence of all this is that I do less and less creative work. I am at the mercy of the world. And since my time on Earth is running short you can well understand how desperate I sometimes feel. I have thought of running off to some remote corner of the Earth, where I might live in peace and do only what I wish to do, but where is that place? Years ago, I thought of going to Tibet or to Nepal or some remote corner of India, but today I haven't the heart to pick myself up and go to such outlandish places. I need some comforts and also some medical attention. And I don't want to leave my son here alone should he be drafted into the military service."

. . . Here, ladies and gentlemen, is the Henry Miller worthy of print! If only there were more of this throughout the book! Here, you have Miller reflecting on his life's ambition, and where it's gotten him. You have an aged Miller, a man who knows his best years are behind him, worrying about his output, worrying about his health, letting another dream go. . . renouncing the thirst for travel that went unquenched for so long in his earlier days. "But where is that place?" By God, there's the man who wrote about his yearning for travel. . . in his FORTIES! He's there, in his home in the Pacific Palisades, wondering where else there is to go. And at the end, the finishing touch, his concern that his son might be drafted into the Vietnam conflict.

Shortly thereafter, Henry Miller and Hoki Tokuda married. The ceremony was held and Dr. Siegel's house. The letters stop, for awhile. When Miller start's writer her again, it's 1968 and she's in Japan. Howard notes that Tokuda-Miller traveled to Japan three times, that year. The first time so that she could be at the side of her ailing father.

The second time, she went to promote a series of Miller's watercolor exhibitions. Actually, lots of people-according to the ticket sales-attended these displays of his work. Miller was ultimately disappointed with the amount of money made from the sale of his work, and it's funny to read him inquiring about and fretting over money.

On her third trip to Japan, she work on a record for Sony, did some interviews for television and print, and managed to do some film work. The movie was most like Kaidan Nobori Ryu (or, The Blind Woman's Curse).

As I stated above, Miller's not very secure in this relationship. However, the "You don't love me," jags become more infrequent during Hoki's second visit to Japan. This time around, he obsesses over money. He does a lot of bitching about the royalties, he's owed. He worries about her not signing off on some income tax papers. He frets over getting the Jaguar fixed.

And yet he does open up a bit more. He doesn't seem to be sending her any more paintings, and I'd say he compensates for this by putting more color into his letters. More of himself turns up. He's quick writing about things happening in the world around him.

There's Bonnie and Clyde, for instance. He hated that film. He writes to his wife about how much he hates that film. He asks her if the Japanese hate that film. He rants about he's going to write an essay, addressed to the Japanese, expressing his hatred for the movie.

He's acting his age, eh?

Here's a passage, from April 13th, 1968, wherein we find a snapshot of life outside of Miller's head; a passage that transcends the emotional turmoil that is Miller day-to-day life:

"I read the other day about how they demonstrated against the American hospital in Tokyo. Good for them, Banzai! If the Japanese were really smart, really farsighted, they will cooperate more and more with Red China, and not U.S. and Germany. We are going to be pushed out of Asia before very long. I listened to a wonderful retired American General the other day, who knows all Asia well and served in Vietnam, and he says the South Vietnamese hate is more than they do the Viet Cong. And I can believe it. You speak of watching the news on TV, the riots in Washington-plus 84 other cities. L.A. was the only city in which there has been no trouble. (A miracle.) But there will be more trouble soon again. The Negroes are not going to follow Dr. King's policy of non-violence, they are going to fight harder and harder. They can cause so much trouble, if they really put their minds to it, that we will have to call our soldiers back from Vietnam to stop the riots here."

Later on the collection, there's another piece of writing dedicated to Yomiuri Shimbun, a copy of which was given to Hoki. It's entitled "On the Pleasures of Rereading." It's another example-another rare example-of Miller putting his intellect to good use and setting aside his almost-infantile desire for attention and emotional nourishment. Listen to this:

"I don't know how it is in Japan, but in America I have the impression that we seldom reread books. Here books (paper backs) are relatively cheap, easily discarded, and quickly forgotten. We do not take pride in exhibiting our personal library, as do the French and Germans, for example. We do not bring our paper backs to a binder and have them bound according to our taste. Nor do I encounter people who are seeking for books they read years ago in order to savor them anew. As with buildings, cars, clothes, wives and mistresses, here nothing lasts very long. We are the very opposite of the ancient Egyptians, who thought in terms of eternity. With us nothing is precious, nothing inspires or awe or reverence."

Passages such as this are all too rare in this collection of imploring, sniveling, manipulative scribblings. Joyce Howard had the audacity to ask "Was it part of his 'scrupluousness' that kept such deep and private emotions out of his literary work?"

I can't help but wonder what in the hell she was reading, or if she hadn't confused him, somehow, with another writer. Reading through this mess, your eyebrows shoot up when you come across lines like "Bob Dylan leaves me stone cold, though he's number one for the teenagers." Then they quickly snap back down to your eyelids when he commences to plead for more assurance that his "Light of Asia" isn't hoing him for notoriety and citizenship.

And you wonder how much of this worry he brought on himself. An uncharitable assessment would be "All of it." Dated April 29th, 1968, we get an unsettling glimpse of what some suspect to have been a reoccurring theme in their relationship:

"The Loujon Press in Arizona, who did the beautiful book on Hans Heichel, is serious about publishing 'The Insomnia Series.' He wants to do an extraordinary job-even better than the Heichel book. Is now trying to find someone to finance it. I will soon start to write the text to go with these water colors. This is where Hoki Tokuda, the siren of Imperial Gardens and Chinatown comes in. If I don't succeed in writing a song for you I will certainly write a text about you. . . In one way or another you will be famous in the next few years-before you are forty!"

(The "Insomnia Series" was published as "Insomnia: Or, The Devil at Large." The text, in the book, is handwritten. The images can be found behind the link, above, on Miller's daughter's website, which you should check out and buy stuff from.)

As I mentioned earlier, the book is divided into three parts. "Falling In Love," Marriage," and "Disillusionment." I've not pulled much from the last part, and I'd prefer not to. You might have guessed that he compares her to a whore, at one point.

They divorced in 1970. That same year, "Insomnia," was published, the film adaptations of Tropic of Cancer (starring Rip Torn as Miller) and Quiet Days in Clichy(with E-Files star, Andrew McCarthy assuming the role of Miller. In Naples, Italy, Miller's book Stand Still Like The Hummingbird won Book of the Year. That would be the first and only prize he ever received for his writing.

Hoki Tokuda-Miller at the age of thirty-one, moved to Marina del Rey and opened a boutique in Beverly Hills. She stayed in touch with Miller until 1975.

And on April 27th, 1996, The Henry Miller Museum of Art opened in the resort town of Omachi, Japan.