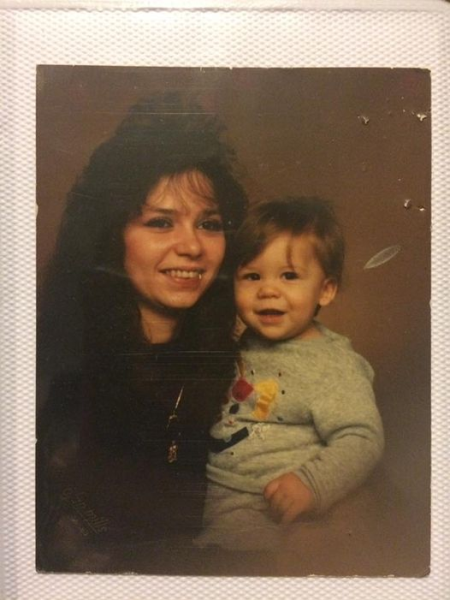

Mom.

I wasn't sure if I wanted to make this post, but it's why I haven't been very present online since getting home. It feels sort of inappropriate to put here, and after a week now it all still feels surreal and inarticulable. But on my way back to Albany last Monday, at 1:11PM, just a couple hours away, I got a call from my sister telling me that my mother had a heart attack and was in the hospital, where they induced a coma to reduce the swelling in her brain. At first, I wasn't sure what to feel. After months with no contact, I had literally gotten a nasty voicemail from her a few days earlier, screaming at me about how selfish I was for "worrying people" and not responding to their calls. To be honest, I actually said I wished she'd die that night, and it wasn't the first time I'd said those words. I hadn't seen her in almost two years. The last time was her pulling over to ask me if I needed a ride anywhere as I was walking up Altamont Ave, but I rejected the offer. I refused to let her visit me after my suicide attempt. My relationship with my parents had been either nonexistent or very toxic over the years. But I don't want to focus on that here.

By Tuesday, more information came in. It wasn't a heart attack; it was cardiac arrest, and was likely due to alcohol. My mother was an alcoholic, and it had plagued my relationship with her since childhood. That night, at midnight, I went to the hospital to visit her and join my family even though I felt so strongly that I didn't want to. The doctors had been cooling her body and began the process of gradually returning her to a normal body temperature. One of three things could happen during this window of a few hours: she'd wake up and show signs of consciousness and deliberate movements, she'd instantly go into a seizure and have to be put back under, or she'd stay just the way she was: in a comatose, vegetative state. When I first walked into the room at the ICU, I instinctively kept to the corner. I felt like I couldn't or shouldn't get too close. Seeing my mother lie there with tubes stuck in her face and her hands contorted into the decorticate posture was strange and unbearable. We all tried to interact with her in hopes of there still being a person inside to hear and feel it. I touched her arm and whispered into her ear, "I don't know if you can hear me, but this could be a great opportunity to start something new." I did know that sometimes people in comas heard and sensed their surroundings even while unconscious, and held out hope that's what was happening. She was able to breathe over the machine, and with each heavy inhale, it would lift her head. At one point, it even looked as if she were about to turn to my brother Bryce. My brain just couldn't compute what I was seeing. She looked like she was simply sleeping, and would open her eyes to us at any second. The hours went by in slow motion.

My mind was racing, thinking of all the years I distanced myself from her and my father. I still felt I did what was right for me and my personal well-being, but if I was being honest it had never been an easy decision, and I was beginning to feel guiltier with every second I sat there. It didn't help that my brother continuously made comments to me about it. After trying to bring up some of the abuse that we endured in the past, and for some of them in the very present, he responded very aggressively, and it was then that I realized that I would have to process those things alone or in therapy, and wouldn't be permitted to openly grieve in the way that I knew I had to. Still, I wanted so badly for her to just wake back up and have a new lease on life--one where she stopped drinking and we could finally try and forge a new relationship. It would be a rabbit hole I would continue to fall down for days to come.

The week crawled by and the process was dragged on. We all knew what was going on; many of us knew we had lost her that Monday. But the hospital kept repeating tests and giving us false hope. For a group of professionals whose hands several lives literally rested in, they were incredibly disorganized. Her cardiologist and the doctors who first took her in didn't even know she drank, in part because she always would lie and our father would back those lies up. When they found out, they said the cardiac arrest made a lot more sense. I had to hear that my mother could drink eight to sixteen containers of beer in a single day, and that she had been drinking for several days straight before this happened. It was proposed that the morning she went into cardiac arrest, it was possibly due to the few hours she'd gone without drinking while asleep--a deadly bout of sudden withdrawal. That last night she was conscious, she had slept on the couch because her and my father were arguing, as usual.

It was the first time the whole family had been together in almost two years, and I hated that it had to be under those circumstances. We all knew my mother would have been so excited we were all together for a change. I saw a lot of old faces I hadn't seen in years, and saw a lot of people cry who I didn't think were capable of it. I cried a lot, too, mostly because of seeing other people crying and hurting. I cried so much that my head hurt each night. It came in waves. We all somehow found brief moments of relief where we made each other laugh, or were able to talk about mundane bullshit.

By Friday, she was no longer breathing over the machines. Her body was being kept alive by modern medicine and technology alone. The EEG came back and verified for us that her brain was dead--the things inside of it that made her an individual human being with a lifetime of memories, thoughts, feelings, regrets, inside jokes, love, and hate, were no longer there. Her brain stem ensured the bare machinery of her body was still functioning. We were taken into the conference room and given "the talk"--the one where a doctor told us what we all already knew: our mother was clinically dead, and it would soon be up to us whether or not we took her off life support. Ultimately, the decision was left to our father, but everyone at first expressed worry that we'd be prematurely killing her, and that maybe we should wait for one of those anomalous miracles people wrote about. Shortly after, we would be met again with aggressive negotiations over her organs, attempting to persuade us to keep her alive so they could pick and choose what to harvest from her. Everyone was very much against it, except for me, but I kept quiet and let everyone else decide. Understandably, most of them were shaken by grief and horrified at the thought of her being dismembered and sent in pieces to other cities around the country, even if it would potentially save someone else.

As the afternoon went on, most of us took individual private moments alone with her behind the curtain. Not being at all spiritual and knowing nothing I said or did would be known by anyone, I remained silent, but still grasped her arm and looked at her face for a few moments. I'd watched it closely that whole week. On Wednesday, it had been puffy from the drugs, and she looked so sad. Her eyebrows were arched and little streams of dried tears ran down her cheeks. It was unlikely her face was actually representing emotion, but that horrific, tortured image would stay with me for the rest of my life. On that final day, she ironically looked perfectly healthy, with full color in her skin and an almost peaceful expression. I looked at her and all I could think was, 'Why did it have to be this way?' I couldn't stop crying. I started feeling angry; angry at her for the decisions she'd made, angry with myself for the decisions I had to make, angry with the industry that preyed on people like her and made so much money off of her addiction and the collective suffering of the family affected by it.

The time came, and we all decided to be in the room together. We had a moment of silence, though most of us couldn't get through it without sobbing. Then the doctors came in and removed the tube. We returned, all placed our hands on her, and tried to not watch the screen as it basically counted down in rhythmic beeps that gradually slowed. It felt like an eternity, but was actually probably around three minutes before her heart officially stopped. Her face was still and purple. Our father opened up a sealed envelope he'd found back at the house. What was inside had been written a couple years earlier. It was in her unmistakable handwriting, plenty of misspelled words, in pen on lined paper. It was a will of sorts she had written sometime after her first or second heart attack years prior. She knew she had nothing to leave any of us because we were poor. She said she wanted to be cremated and that there be no funeral so no one would be burdened by the costs she knew none of us would be able to afford. There was love and apologies in it, but it was short. She knew that she would die one day because of her lifestyle choices.

She was only 50. I was only 30. Alcohol killed her. She didn't deserve this death, and we didn't deserve witnessing it. I forgave her, even if I never got the apologies I'd always wanted from her. Part of me wished I'd been stronger and stuck around for the good moments my siblings who had shown more patience had gotten to share with her over the years. I always told myself I'd feel relief at her death, but I didn't, at least not at first. I felt torn apart. All I could do was cry and hug my brothers and sister. We were all forever changed in that room. I hoped things would be altered in a positive way from all of this, though I knew in my heart that it wouldn't, and was determined to try and be more present, though I knew I'd never be able to be.

My mother was dead. I watched her heart stop. It still hardly felt real. While I had convinced myself over the years that I "didn’t have a mom", and that I'd accepted I'd never get to fix things with her, there was now a finality to it that made it more real than it ever had been. We both lost our chances to make amends. Everyone seemed to have trouble walking back down the hall. We kept moving the goal post, finding new reasons to not exit the hospital, as if it wouldn't be entirely real as long as we stayed in that room with her body forever.

My mother, as we all were, was a human being who was complex and neither all good nor all bad. She was the product of her own shitty upbringing, struggles, and traumas, and while there was no excuse for some of the things we do to others, we should all try to understand why people did the things they do. I felt I certainly understood her. She had feelings, even if I never got to see or hear them all, and she must have loved me to some extent, even if I found it so hard to believe all those years. For better or for worse, she was why I am straightedge. She was why I would always love country music, the movie Grease, and the word "sike". I had inherited mental health issues, mannerisms, traditions, some of my sense of humor, and language from her. I didn't like all the parts of me she gave me, but they were there and were undeniable. I was a part of her and she was a part of me. There were memories I would always cherish that I didn't usually talk about. I wished so badly things could have been different, but they weren't, and now I and the family members I'd felt it necessary to keep at arm's length for so long had to figure out how to continue living without her. I hoped we keep closer, but knew we wouldn't. This was perhaps the hardest thing I'd ever endured in my adult life.