African Empires

Popular culture's depiction of the pre-colonial peoples of the non-European world is a shameful thing, and the prevailing view of Africa is an excellent example of this. For whatever reason, the most common viewpoint seems to be that the peoples of Africa were a race of "noble savages" who lived, child-like, in an idyllic but abysmally primitive world virtually waiting around for the big bag European bogeyman to show up and carry them off into slavery. In those rare instances when the peoples of Africa are given any credit of active agency, it is in the form of the Zulus (who are in turn belittled as a violent people whose victory over the British at Isandlwana was due only to their superior weight of numbers). If one were to listen to popular imagination, one might think that Africa was already colonized and subjugated by the Europeans by the dawning of the steam age. In fact, the majority of the continent remained firmly in African hands until almost the turn of the 20th century, and the European powers only began negotiating the colonial boundaries of Africa (with each other, of course, and not the Africans themselves: why bring rightful landowners into these things?) at the Berlin Conference of 1884. As with the Native Americans and the peoples of Asia, Africans were not passive recipients of European conquest: they were intelligent, active players in the process who attempted to capitalize upon the situation as best they could.

In fact, Africa has a long history of native imperialism. Numerous African cultures throughout history have developed powerful empires that oversaw complicated social structures, ruled groups of people with different cultural and religious backgrounds, developed large-scale commerce, engaged in slavery and the slave trade, utilized large and disciplined armies, and were effectively just as "imperial" as the would-be European empires expanding across the globe at the time (not that the Europeans were prepared to give them any such credit). Ultimately almost all of these large-scale African societies would be defeated and conquered by foreign powers (Ethiopia being the key exception: it was not "colonized" until the Italian invasion in 1936). This was largely due to advantages in military technology and infrastructure developed by the Europeans in the 19th century. However, this is not to say that the African powers were technophobic or militarily backward. Many of them utilized sizable and highly disciplined military forces armed with metal weaponry and firearms. Although the African powers did not historically have the advantage of Europe's industrial technology, there is no reason to suppose that they would have failed to take advantage of it had it become available. Historically, African military systems changed in the 19th century to adapt to the greater volume of firearms being introduced by foreign trade. It is only a short step toward envisioning an indigenously industrialized Africa in an alternate history.

Certainly, there were small-scale tribal groups who never became imperial powers (the Maasai are an excellent example), but even these were far from passive recipients of foreign invasion. In addition, the nation of Liberia deserves a special mention. Liberia was a colony founded by the United States in the early 19th century as a place for freed slaves to be relocated to. While on the surface this might seem to have been a fantastic idea (both the American Colonization Society and the emigres themselves seemed to think so), in fact it represented yet another example of foreign conquest of African territory. Though of African descent, the Liberian colonists had far more in common with white Americans than they did with the indigenous Africans living in inland Liberia.

To conclude, there is a wellspring of available fashion inspiration to be found in 19th century Africa. In addition to using European-style garments and uniforms as the base for colonial African steampunk costumes, clothing styles drawn from pre-colonial 19th century civilizations are perfectly viable sources for inspiration. As with all forms of steampunk fashion, a steampunk adaptation here can be as simple as adding small technological conveniences (perhaps vintage sunglasses or a timepiece) or as complex as a full-scale mixture of cultures and technologies (consider an African garment incorporating Japanese silks obtained through trade).

My apologies for slacking off on doing these posts. I'm afraid I'm in the middle of writing a novel, and if I go much slower my agent will kill me.

Regards, etc.,

-G. D. Falksen

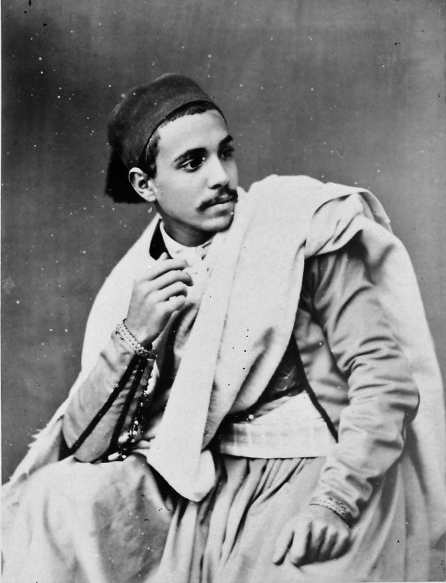

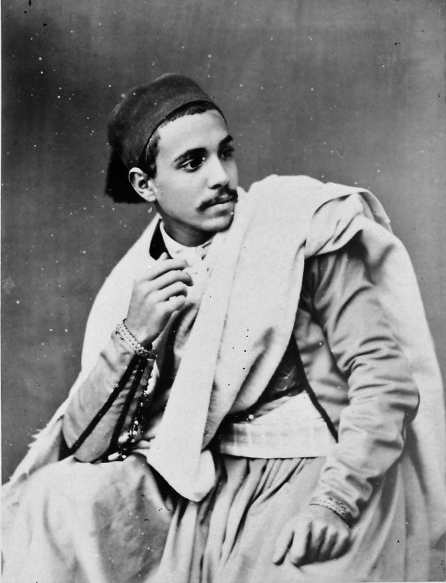

An Algerian man.

The Oba (political and spiritual leader) of Benin, Ovonramwen, in 1897. Alas, in this image he is seen being transported into exile.

Yohannes IV, 19th century emperor of Ethiopia.

A South African witchdoctor taking snuff.

A young woman and child.

Riflemen serving under Samori Ture.

Samori himself.

African soldiers with a mix of firearms and melee weaponry.

A king of Sennar, 1821.

Maasai warriors.

Zulu warriors. Though they did not utilize firearms, the Zulu had an extremely advanced system of tactical organization, including flanking maneuvers, line-breaking maneuvers, and supply maintenance.

J. J. Roberts, first president of the Independent Republic of Liberia.

E. J. Roye, president of Liberia from 1870-1871.

African soldiers in European uniform.

A sketch of an African soldier in service to a European power.

In fact, Africa has a long history of native imperialism. Numerous African cultures throughout history have developed powerful empires that oversaw complicated social structures, ruled groups of people with different cultural and religious backgrounds, developed large-scale commerce, engaged in slavery and the slave trade, utilized large and disciplined armies, and were effectively just as "imperial" as the would-be European empires expanding across the globe at the time (not that the Europeans were prepared to give them any such credit). Ultimately almost all of these large-scale African societies would be defeated and conquered by foreign powers (Ethiopia being the key exception: it was not "colonized" until the Italian invasion in 1936). This was largely due to advantages in military technology and infrastructure developed by the Europeans in the 19th century. However, this is not to say that the African powers were technophobic or militarily backward. Many of them utilized sizable and highly disciplined military forces armed with metal weaponry and firearms. Although the African powers did not historically have the advantage of Europe's industrial technology, there is no reason to suppose that they would have failed to take advantage of it had it become available. Historically, African military systems changed in the 19th century to adapt to the greater volume of firearms being introduced by foreign trade. It is only a short step toward envisioning an indigenously industrialized Africa in an alternate history.

Certainly, there were small-scale tribal groups who never became imperial powers (the Maasai are an excellent example), but even these were far from passive recipients of foreign invasion. In addition, the nation of Liberia deserves a special mention. Liberia was a colony founded by the United States in the early 19th century as a place for freed slaves to be relocated to. While on the surface this might seem to have been a fantastic idea (both the American Colonization Society and the emigres themselves seemed to think so), in fact it represented yet another example of foreign conquest of African territory. Though of African descent, the Liberian colonists had far more in common with white Americans than they did with the indigenous Africans living in inland Liberia.

To conclude, there is a wellspring of available fashion inspiration to be found in 19th century Africa. In addition to using European-style garments and uniforms as the base for colonial African steampunk costumes, clothing styles drawn from pre-colonial 19th century civilizations are perfectly viable sources for inspiration. As with all forms of steampunk fashion, a steampunk adaptation here can be as simple as adding small technological conveniences (perhaps vintage sunglasses or a timepiece) or as complex as a full-scale mixture of cultures and technologies (consider an African garment incorporating Japanese silks obtained through trade).

My apologies for slacking off on doing these posts. I'm afraid I'm in the middle of writing a novel, and if I go much slower my agent will kill me.

Regards, etc.,

-G. D. Falksen

An Algerian man.

The Oba (political and spiritual leader) of Benin, Ovonramwen, in 1897. Alas, in this image he is seen being transported into exile.

Yohannes IV, 19th century emperor of Ethiopia.

A South African witchdoctor taking snuff.

A young woman and child.

Riflemen serving under Samori Ture.

Samori himself.

African soldiers with a mix of firearms and melee weaponry.

A king of Sennar, 1821.

Maasai warriors.

Zulu warriors. Though they did not utilize firearms, the Zulu had an extremely advanced system of tactical organization, including flanking maneuvers, line-breaking maneuvers, and supply maintenance.

J. J. Roberts, first president of the Independent Republic of Liberia.

E. J. Roye, president of Liberia from 1870-1871.

African soldiers in European uniform.

A sketch of an African soldier in service to a European power.