The fruit, the real fruit of all mankind...

Dostoevsky Draws Shakespeare: The Fascinating Discovery

Оригинал взят у tec_tecky в Dostoevsky Draws Shakespeare: The Fascinating Discovery

Annie Martirosyan

Linguist, philologist, Shakespeare researcher

Suddenly, Feodor Mikhailovich put down his tea cup carelessly on the draft, stood up and started his habitual intellectual ritual when he would walk to and fro in the room and make up his characters' speeches out loud...

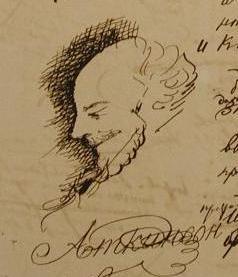

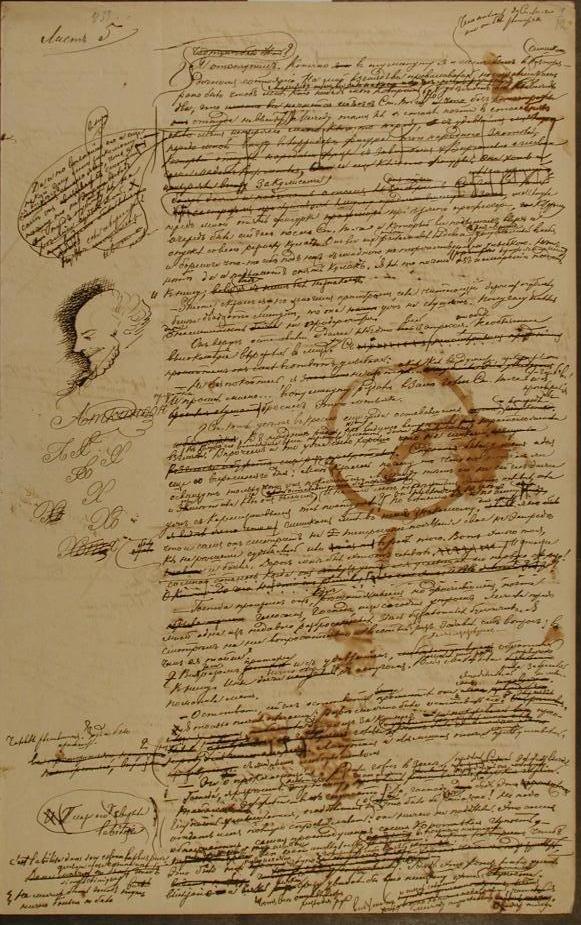

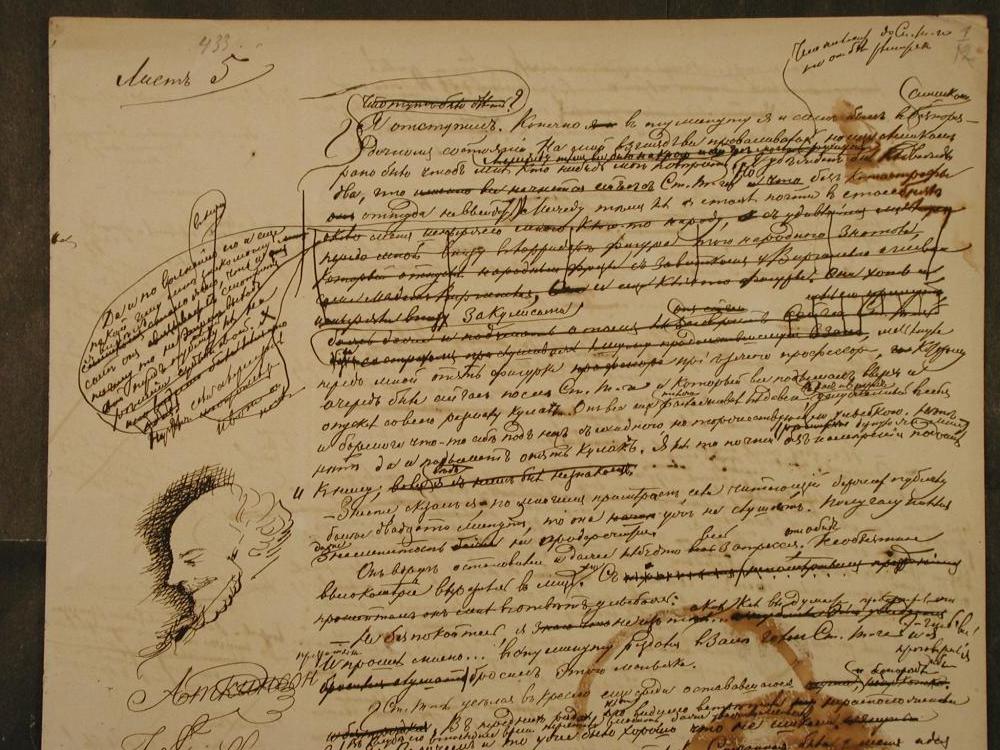

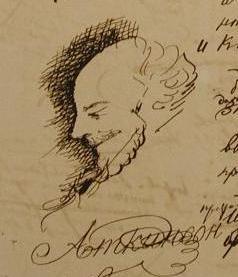

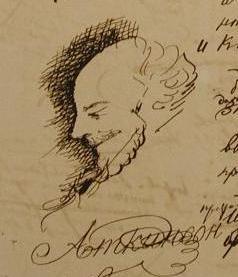

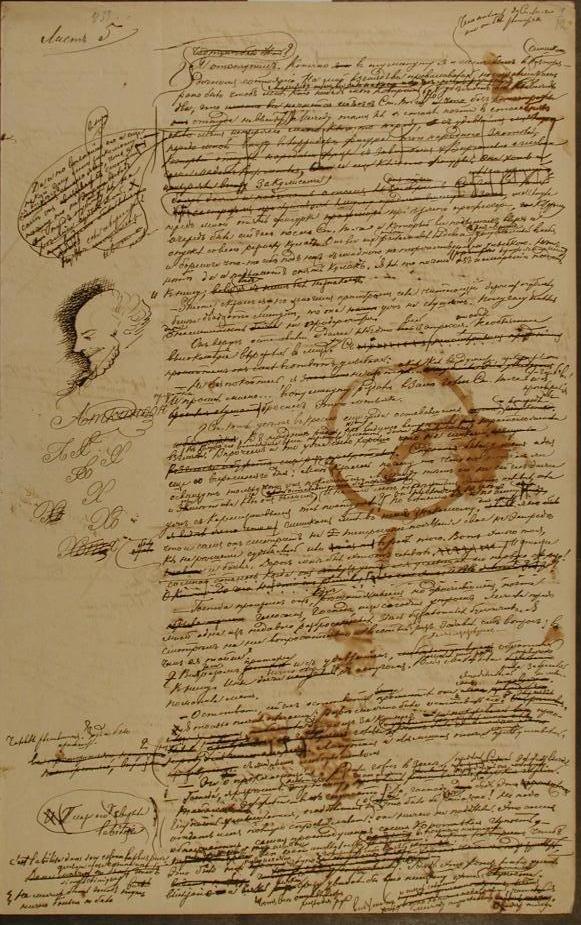

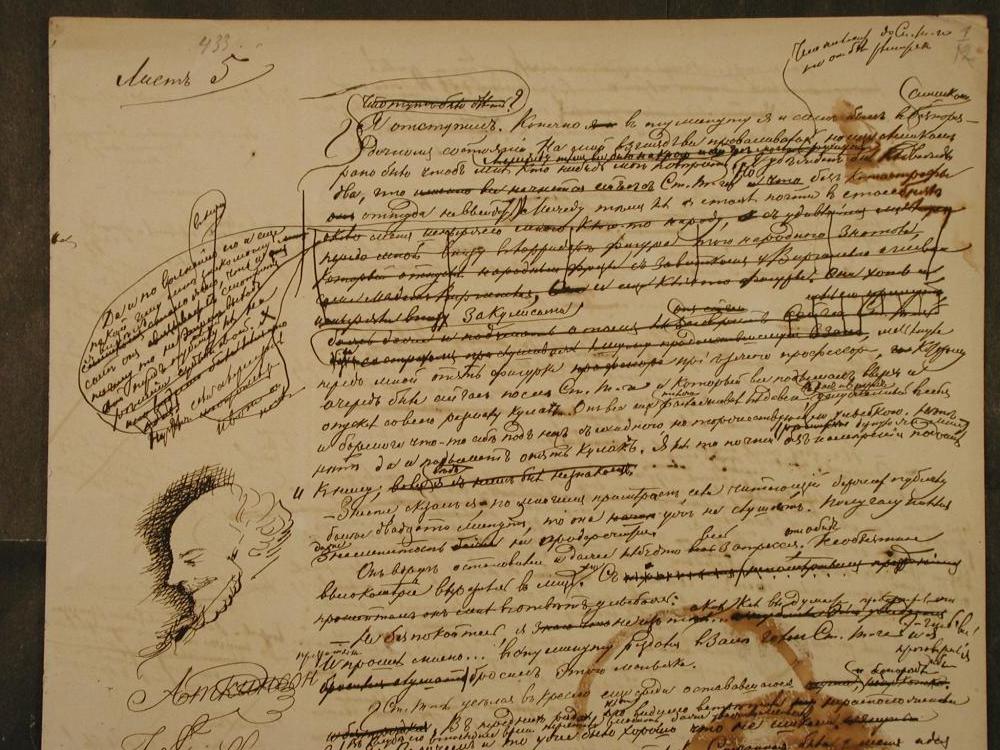

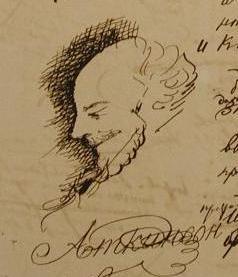

It is the big stain from the tea cup that you see on the page at once. Feodor Mikhailovich was an avid tea drinker. The handwriting is hardly legible; scribbles, jots and marginalia are scattered naughtily across the page. On the left-hand side is a curious drawing of a man's head, with the familiar broad bald forehead, curly hair and a pointed beard, looking down, thoughtfully, copying Dostoevsky's own posture in the famous portrait by Vasily Perov. Under the drawing is a carefully handwritten name - "Atkinson", together with equally carefully calligraphed random capital letters. Dostoevsky liked to practise his handwriting. On the whole, it is a revealing manuscript from the frenzied genius working on his most arresting and dynamic novel - Demons (Besy).

In July 2014, Professor Boris Tikhomirov, Deputy Director of the Literary-Memorial Museum of F. M. Dostoevsky in St. Petersburg, sent a letter to Professor Vladimir Zakharov, President of The International Dostoevsky Society, attaching a manuscript page (c.1871-2) from Dostoevsky's novel Demons which he had received from Zakharov earlier for examination. The object of examination was the elusive drawing. The text across the drawing includes Stepan Trofimovich Verkhoventsky's famous vociferation:

"Всё недоумение лишь в том, что прекраснее: Шекспир или сапоги, Рафаэль или петролей? [...] А я объявляю, что Шекспир и Рафаэль - выше освобождения крестьян, выше народности, выше социализма, выше юного поколения, выше химии, выше почти всего человечества, ибо они уже плод, настоящий плод всего человечества и может быть высший плод, какой только может быть!"

"The whole perplexity lies in just what is more beautiful: Shakespeare or boots, Raphael or petroleum? [...] I proclaim that Shakespeare and Raphael are higher than the emancipation of the serfs, higher than nationality, higher than socialism, higher than the younger generation, higher than chemistry, higher than almost all mankind, for they are already the fruit, the real fruit of all mankind, and maybe the highest fruit there ever may be!"

(trans. by Pevear and Volokhonsky)

[The fruit, the real fruit of all mankind...]

A comparative look at Shakespeare's Chandos portrait is not even needed - Stepan Trofimovich helps to place the man in the drawing. The "Atkinson" Dostoevsky could possibly have known of would likely be Thomas Witlam Atkinson or J. Beavington Atkinson.

Dr Nikolay Zakharov, philologist and Shakespeare researcher at The Moscow University for the Humanities, believes that Dostoevsky could have heard of the English architect and travel writer Thomas Witlam Atkinson (1799-1831). The English critic and writer J. Beavington Atkinson is a more likely candidate for the "Atkinson" under the drawing. Zakharov notes that in his diary Dostoevsky mentions an anonymous article called "Angliyskaya kniga o russkom isskustve i russkikh khudozhnikakh" ("An English Book about the Russian Art and Russian Artists") which retells and includes excerpts from J. B. Atkinson's book An Art Tour to Northern Capitals of Europe (London, 1873). Zakharov assumes Dostoevsky would have been provoked by Atkinson's claims that "up to now, the Russian school of art has not developed new styles or new themes" (from personal correspondence with Nikolay Zakharov, Autumn 2014).

The drawing is not a depiction of either of the Atkinsons - it depicts Shakespeare, credibly and most accurately. It is likely that Dostoevsky wrote the name together with the other letters not connected with the text of the novel randomly on the page and it happens to be quite close to his drawing of Shakespeare. Probably Atkinson was on his mind at the time of writing and indeed, for more practical reasons, "Atkinson" is nearly a neat isogram to practise one's handwriting on.

The Dostoevsky experts behind the discovery, Tikhomirov and Zakharov, have now confirmed the authenticity of the image as Dostoevsky's drawing of Shakespeare. As to Dostoevsky's possession of a Chandos copy, Nikolay Zakharov romantically suggests that the little anecdote which appeared next to Dostoevsky's short story Bobok (written shortly after Demons) in the 6th issue of his journal Grazhdanin on 5 February 1873, might as well be autobiographical:

I have recently heard the following story. A gentleman entered a St. Petersburg bakery. The boy selling him a bun (kalatch) was staring at him.

"Why are you staring at me?", the buyer asked.

"I am staring at you because you look like Shakespeare."

"Like Shakespeare? How come you know him?"

"Of course I know him, he is my favourite writer, I read his works and I have his portrait too!"

... Stepan Trofimovich finished his address to the festival and fell silent. His creator ran to his desk, pushed aside his now cold tea and hastily scribbled down the speech whilst it was fresh in his mind. He sat there for a while staring at the distant face in his drawing, then stood up and shuffled into the kitchen to make fresh tea, his mind centuries back, silently dialoguing with the man in the drawing - a dialogue more intellectually bonded than even Bakhtin would envisage later...

The material is prepared and the manuscript images reproduced with the kind permission of Professor Vladimir Zakharov and Professor Boris Tikhomirov, with huge thanks to Dr. Nikolay Zakharov for fruitful correspondence. No part of the material and the images may be copied or reproduced in any form without the express consent of Vladimir Zakharov and Boris Tikhomirov.

Оригинал взят у tec_tecky в Dostoevsky Draws Shakespeare: The Fascinating Discovery

Annie Martirosyan

Linguist, philologist, Shakespeare researcher

Suddenly, Feodor Mikhailovich put down his tea cup carelessly on the draft, stood up and started his habitual intellectual ritual when he would walk to and fro in the room and make up his characters' speeches out loud...

It is the big stain from the tea cup that you see on the page at once. Feodor Mikhailovich was an avid tea drinker. The handwriting is hardly legible; scribbles, jots and marginalia are scattered naughtily across the page. On the left-hand side is a curious drawing of a man's head, with the familiar broad bald forehead, curly hair and a pointed beard, looking down, thoughtfully, copying Dostoevsky's own posture in the famous portrait by Vasily Perov. Under the drawing is a carefully handwritten name - "Atkinson", together with equally carefully calligraphed random capital letters. Dostoevsky liked to practise his handwriting. On the whole, it is a revealing manuscript from the frenzied genius working on his most arresting and dynamic novel - Demons (Besy).

In July 2014, Professor Boris Tikhomirov, Deputy Director of the Literary-Memorial Museum of F. M. Dostoevsky in St. Petersburg, sent a letter to Professor Vladimir Zakharov, President of The International Dostoevsky Society, attaching a manuscript page (c.1871-2) from Dostoevsky's novel Demons which he had received from Zakharov earlier for examination. The object of examination was the elusive drawing. The text across the drawing includes Stepan Trofimovich Verkhoventsky's famous vociferation:

"Всё недоумение лишь в том, что прекраснее: Шекспир или сапоги, Рафаэль или петролей? [...] А я объявляю, что Шекспир и Рафаэль - выше освобождения крестьян, выше народности, выше социализма, выше юного поколения, выше химии, выше почти всего человечества, ибо они уже плод, настоящий плод всего человечества и может быть высший плод, какой только может быть!"

"The whole perplexity lies in just what is more beautiful: Shakespeare or boots, Raphael or petroleum? [...] I proclaim that Shakespeare and Raphael are higher than the emancipation of the serfs, higher than nationality, higher than socialism, higher than the younger generation, higher than chemistry, higher than almost all mankind, for they are already the fruit, the real fruit of all mankind, and maybe the highest fruit there ever may be!"

(trans. by Pevear and Volokhonsky)

[The fruit, the real fruit of all mankind...]

A comparative look at Shakespeare's Chandos portrait is not even needed - Stepan Trofimovich helps to place the man in the drawing. The "Atkinson" Dostoevsky could possibly have known of would likely be Thomas Witlam Atkinson or J. Beavington Atkinson.

Dr Nikolay Zakharov, philologist and Shakespeare researcher at The Moscow University for the Humanities, believes that Dostoevsky could have heard of the English architect and travel writer Thomas Witlam Atkinson (1799-1831). The English critic and writer J. Beavington Atkinson is a more likely candidate for the "Atkinson" under the drawing. Zakharov notes that in his diary Dostoevsky mentions an anonymous article called "Angliyskaya kniga o russkom isskustve i russkikh khudozhnikakh" ("An English Book about the Russian Art and Russian Artists") which retells and includes excerpts from J. B. Atkinson's book An Art Tour to Northern Capitals of Europe (London, 1873). Zakharov assumes Dostoevsky would have been provoked by Atkinson's claims that "up to now, the Russian school of art has not developed new styles or new themes" (from personal correspondence with Nikolay Zakharov, Autumn 2014).

The drawing is not a depiction of either of the Atkinsons - it depicts Shakespeare, credibly and most accurately. It is likely that Dostoevsky wrote the name together with the other letters not connected with the text of the novel randomly on the page and it happens to be quite close to his drawing of Shakespeare. Probably Atkinson was on his mind at the time of writing and indeed, for more practical reasons, "Atkinson" is nearly a neat isogram to practise one's handwriting on.

The Dostoevsky experts behind the discovery, Tikhomirov and Zakharov, have now confirmed the authenticity of the image as Dostoevsky's drawing of Shakespeare. As to Dostoevsky's possession of a Chandos copy, Nikolay Zakharov romantically suggests that the little anecdote which appeared next to Dostoevsky's short story Bobok (written shortly after Demons) in the 6th issue of his journal Grazhdanin on 5 February 1873, might as well be autobiographical:

I have recently heard the following story. A gentleman entered a St. Petersburg bakery. The boy selling him a bun (kalatch) was staring at him.

"Why are you staring at me?", the buyer asked.

"I am staring at you because you look like Shakespeare."

"Like Shakespeare? How come you know him?"

"Of course I know him, he is my favourite writer, I read his works and I have his portrait too!"

... Stepan Trofimovich finished his address to the festival and fell silent. His creator ran to his desk, pushed aside his now cold tea and hastily scribbled down the speech whilst it was fresh in his mind. He sat there for a while staring at the distant face in his drawing, then stood up and shuffled into the kitchen to make fresh tea, his mind centuries back, silently dialoguing with the man in the drawing - a dialogue more intellectually bonded than even Bakhtin would envisage later...

The material is prepared and the manuscript images reproduced with the kind permission of Professor Vladimir Zakharov and Professor Boris Tikhomirov, with huge thanks to Dr. Nikolay Zakharov for fruitful correspondence. No part of the material and the images may be copied or reproduced in any form without the express consent of Vladimir Zakharov and Boris Tikhomirov.