Salzburg 2010

Salzburg this year meant Phèdre with Sunnyi Melles, rain and sunshine mixed, and staying in Leopoldskron, aka Max Reinhardt's old residence. For Americans: it's also where they shot something called The Sound of Music, but seriously, if it's the grandsegnieur of the German theatre who basically invented both grand and small scale production, not to mention festivals, versus a musical that has the barbarity of pairing Schnitzel with noodles - which you never ever eat together - there's no competition as to what I get misty-eyed over.Anyway, my trusty camera and I were busy, in rain and sunshine alike, because Leopoldskron is a hotel mostly used for seminars these days and thus not really open for tourism, meaning I won't get there again soon.

Racine isn't often played in the German-speaking theatre (back in the 18th century we had a big showdown between Shakespeare followers and French Classicism followers; the Shakespeare guys won), so chances are I won't see another Phaedra son, either. The production was modern dress with minimalistic stage design (a movable screen showing black or white which was turned as the scenes ended, and the constant sound of the ocean, which given the eventual fate of Hippolytos was very apropos), and the actors good, although I have to say that the crucial scene where Phaedra finally admits her love out loud to Hippolytos was played over the top on the part of both actors and thus looked involuntarily funny, inducing laughs instead of awed silence. (Sidenote: discussing this afterwards, another theatre goer said to me that they couldn't help it because a woman trying to strip and ravish an unwilling man "always is funny, as opposed to the reverse". Leaving aside long and problematic histories of bodice ripping and gender roles, I disagree. You can achieve a different effect if you stage it right. TV example from BTVS: Take the brief scene of Faith deflowering Xander for stress relief in The Zeppo - which is played for laughs, and he's not unwilling, just surprised - versus the serious scene between them in Consequences where he explicitly doesn't want sex and Faith enjoys the power her physical superiority gives her; definitely no giggles there.) Also I thought the very best actors were in supporting roles, Therese Affolter as Oenone and Paulus Manker as Theseus, helped, admittedly, by Theseus being arguably the most morally ambiguous and layered character in the play. It's basically a Harry Lime sort of role in that he doesn't show up until late in the play and is only in a few scenes, but a) he's talked about much before and b) the actor is good enough that he seems to be far more present. Also I thought againt hat a device Racine meant to give the audience more sympathy for Phaedra - blaming Oenone for most of her actions - works in the opposite way for me - I kept inwardly yelling at Phaedra to own her responsibility instead of shifting them on her servant and driving the poor woman to suicide. Ah, for Medea or Clytaimnestra who never pull something as lame as "my servant made me do it". The final scene, though, with Phaedra dying and Theseus struggling with both what he did and her death - that was fantastically played, and we were all fulll of awe.

Now, on to the pictorial exploration.

Back when Max Reinhardt bought Leopoldskron and invented the Salzburg Festival, there was much "who the hell does he think he is?", both for antisemitic reasons (he was Jewish with no intention to convert, unlike his chief critic Karl Krauss) and for what British tabloids would probably call luvvie resentment. Reinhardt had started out as an actor, had quickly discovered his talent for directing, hit the big time in Berlin and came up both with grand scale productions (think Cecil B. De Mille in Hollywood terms) and intimate small stages (he intended the Studiobühne, i.e. having a small stage for intimate plays along with a big stage for the mass productions in the same theatre. His incredibly detailed stage manuscripts survive so you can reconstruct a lot of his productions, and the most amazing thing is that the actors, usually prone to being micromanaged in their movements, all went misty eyed about him for the rest of their lives. (In the Brecht and Bergner anecdote I related a few entries back, when he refers to "Max" she immediately knew whom he was talking about because there was only one if you were in the German theatre for the first half of the 20th century.) He only tried his hand on film once, and then he was already old and in exile, so the Hollywood Midsummer Night's Dream is a very mixed affair, but it gives at least a hint of what a Reinhardt production was like. (He had gone on world wide tour with that play before WWI already.) In terms of the Salzburg Festival, it was Reinhardt who had the idea and who commissioned Hugo von Hofmansthal who write the Everyman play that is staged to this day, and who then got the archbishop of Salzburg to agree that all the churches of Salzburg would ring their bells at exactly the point where the play needed them to.

Leopoldskron served as Reinhardt's residence and Festival central until he went into exile during the Third Reich. He died before the war ended, and never saw it again. The reason why it ended up as the location for The Sound of Music, though, was that his two sons, Gottfried and Wolfgang, had reccommended it as both beautiful and private, hence ideal for filming within in Salzburg. And now, here it is:

You can see the Salzburger Feste in the background:

As for the inside of Leopoldskron, here we have the stairs:

The former ballroom:

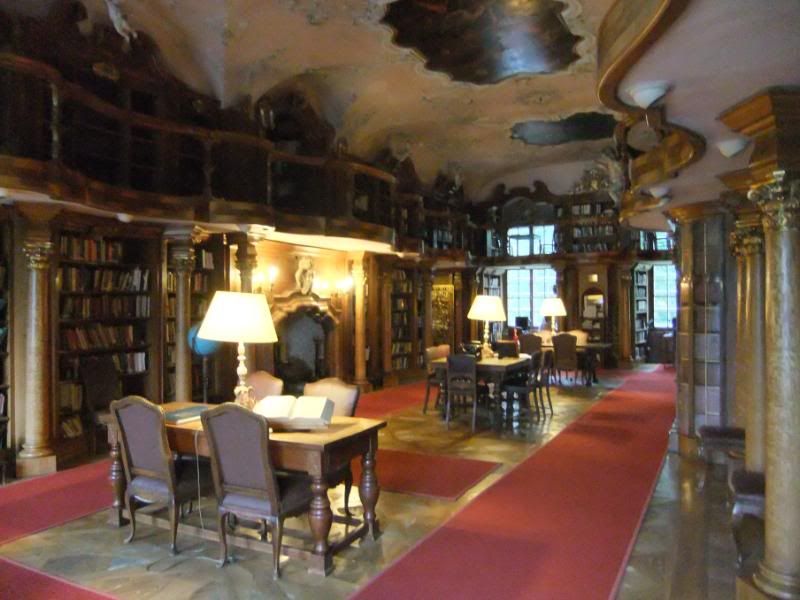

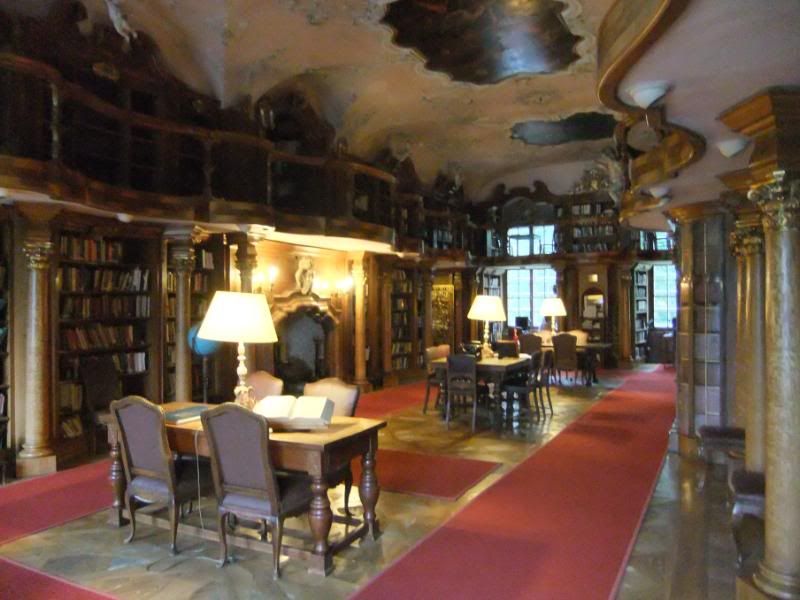

The library:

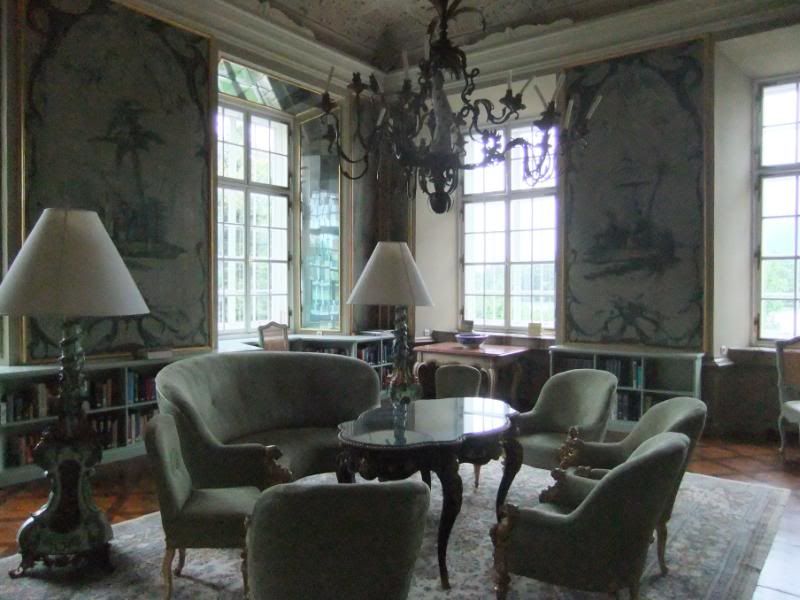

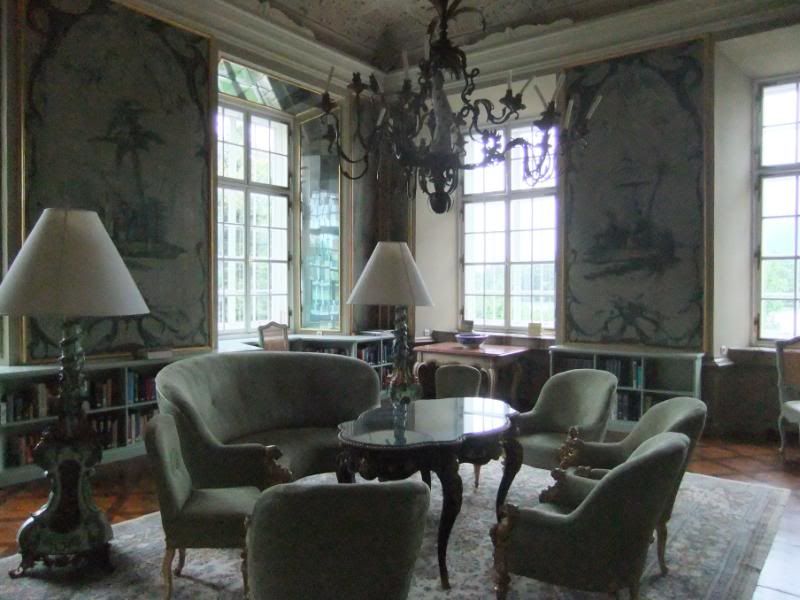

The Chinese Salon:

And another look from outside:

Armed with an umbrella, I went to town in order to see my play. Of course, this was when there was finally some sunshine (temporarily - it's now raining again), so I could not resist photographing Salzburg sites again as well. Here's the Salzburger Feste in sunshine:

The cathedral, all Austrian baroque:

Mozart's birthplace:

And yours truly, signing off:

Racine isn't often played in the German-speaking theatre (back in the 18th century we had a big showdown between Shakespeare followers and French Classicism followers; the Shakespeare guys won), so chances are I won't see another Phaedra son, either. The production was modern dress with minimalistic stage design (a movable screen showing black or white which was turned as the scenes ended, and the constant sound of the ocean, which given the eventual fate of Hippolytos was very apropos), and the actors good, although I have to say that the crucial scene where Phaedra finally admits her love out loud to Hippolytos was played over the top on the part of both actors and thus looked involuntarily funny, inducing laughs instead of awed silence. (Sidenote: discussing this afterwards, another theatre goer said to me that they couldn't help it because a woman trying to strip and ravish an unwilling man "always is funny, as opposed to the reverse". Leaving aside long and problematic histories of bodice ripping and gender roles, I disagree. You can achieve a different effect if you stage it right. TV example from BTVS: Take the brief scene of Faith deflowering Xander for stress relief in The Zeppo - which is played for laughs, and he's not unwilling, just surprised - versus the serious scene between them in Consequences where he explicitly doesn't want sex and Faith enjoys the power her physical superiority gives her; definitely no giggles there.) Also I thought the very best actors were in supporting roles, Therese Affolter as Oenone and Paulus Manker as Theseus, helped, admittedly, by Theseus being arguably the most morally ambiguous and layered character in the play. It's basically a Harry Lime sort of role in that he doesn't show up until late in the play and is only in a few scenes, but a) he's talked about much before and b) the actor is good enough that he seems to be far more present. Also I thought againt hat a device Racine meant to give the audience more sympathy for Phaedra - blaming Oenone for most of her actions - works in the opposite way for me - I kept inwardly yelling at Phaedra to own her responsibility instead of shifting them on her servant and driving the poor woman to suicide. Ah, for Medea or Clytaimnestra who never pull something as lame as "my servant made me do it". The final scene, though, with Phaedra dying and Theseus struggling with both what he did and her death - that was fantastically played, and we were all fulll of awe.

Now, on to the pictorial exploration.

Back when Max Reinhardt bought Leopoldskron and invented the Salzburg Festival, there was much "who the hell does he think he is?", both for antisemitic reasons (he was Jewish with no intention to convert, unlike his chief critic Karl Krauss) and for what British tabloids would probably call luvvie resentment. Reinhardt had started out as an actor, had quickly discovered his talent for directing, hit the big time in Berlin and came up both with grand scale productions (think Cecil B. De Mille in Hollywood terms) and intimate small stages (he intended the Studiobühne, i.e. having a small stage for intimate plays along with a big stage for the mass productions in the same theatre. His incredibly detailed stage manuscripts survive so you can reconstruct a lot of his productions, and the most amazing thing is that the actors, usually prone to being micromanaged in their movements, all went misty eyed about him for the rest of their lives. (In the Brecht and Bergner anecdote I related a few entries back, when he refers to "Max" she immediately knew whom he was talking about because there was only one if you were in the German theatre for the first half of the 20th century.) He only tried his hand on film once, and then he was already old and in exile, so the Hollywood Midsummer Night's Dream is a very mixed affair, but it gives at least a hint of what a Reinhardt production was like. (He had gone on world wide tour with that play before WWI already.) In terms of the Salzburg Festival, it was Reinhardt who had the idea and who commissioned Hugo von Hofmansthal who write the Everyman play that is staged to this day, and who then got the archbishop of Salzburg to agree that all the churches of Salzburg would ring their bells at exactly the point where the play needed them to.

Leopoldskron served as Reinhardt's residence and Festival central until he went into exile during the Third Reich. He died before the war ended, and never saw it again. The reason why it ended up as the location for The Sound of Music, though, was that his two sons, Gottfried and Wolfgang, had reccommended it as both beautiful and private, hence ideal for filming within in Salzburg. And now, here it is:

You can see the Salzburger Feste in the background:

As for the inside of Leopoldskron, here we have the stairs:

The former ballroom:

The library:

The Chinese Salon:

And another look from outside:

Armed with an umbrella, I went to town in order to see my play. Of course, this was when there was finally some sunshine (temporarily - it's now raining again), so I could not resist photographing Salzburg sites again as well. Here's the Salzburger Feste in sunshine:

The cathedral, all Austrian baroque:

Mozart's birthplace:

And yours truly, signing off: