“Our home is not the same”

There seemed to have been a baby born in just about every far western town in NSW: Brewarrina, Dubbo, Parkes - symptoms of a hard life, travelling to where the work was, and a slow and relentless drift towards the Big Smoke. To Sydney, in the early 30s, where the O’Neale family, parents and their six children, made their home at 81 Renwick St Leichhardt. Father, Christopher Joseph, became a tram conductor - it was a steady income but it had to stretch a very long way. The children grew up, left school, found work themselves. Life stretched out before them.

As far as I can establish, all the boys (five of the six children) attended school at Christian Brothers Lewisham. As the boys grew up, and left school they moved into the workforce: Lionel worked in a factory, Jack was a compositor, working for the Australian Medical Publishing Company; next boy down, Christopher (known as Chicka) was also a compositor (machine mechanic), and the twins, Paddy and Keith (‘Mick’) eventually entered the NSW Public Service.

We have no letters from them, no photographs or other physical mementoes. Who knows where these things vanished to over the past 70 years! (How easy is it for all traces of someone to disappear...) Speaking with those that do have some recollections of them, we know that Jack was an athletic young man, a competitive boxer. He’s been described to me as good looking, with blue eyes. Also, apparently, something of a hero to the younger boys. Chicka was also fair with blue eyes, and a very gentle soul. Both were about 5’8” tall, Jack possibly just about a half inch taller.

With war clouds gathering, in January 1939 Jack enlisted in the Militia Forces (the Reserves); Chicka joined the Navy in March 1939, and reported for duty post-mobilisation at HMAS Penguin on 26 August 1939. Just in time for the outbreak of the Second World War. He was just 19.

Once training was completed, Chicka did a number of stints on various vessels, before being promoted to Able Seaman and transferred to the HMAS Perth on 1 July 1941.

Jack, in the meantime, had been called up, and taken his oath of enlistment at Victoria Barracks in Paddington (in Sydney) on 10 July 1940. He spent time with a number of different battalions, before being transferred to the 2/3 Reserve Motor Transport Company in March 1941.

On 10 April 1941, Jack embarked for Singapore onboard HMT 26 (‘Orcades’), arriving 24 April 1941, just the day before Anzac Day.

Once in Singapore, Jack served along the Malay Peninsula, before being caught up in the chaotic withdrawal back, back, back...and then the eventual capitulation to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. The next record we have is from Changi, and then on 8 July 1942 he embarked as part of ‘B’ Force on the Ubi Maru to Borneo. To the Sandakan Prisoner of War Camp.

The Perth was undergoing a refit at the time Chicka joined it, (it spent time in the Fitzroy Dock at Cockatoo Island - which I can see from my living room window). Following exercises off the coast, the ship left Australia for Java on 14 February 1942, arriving on 24 February 1942.

He survived the sinking of the Perth in the Sunda Straits, and the next record indicates that he was imprisoned in the so-called’Bicycle Camp’ in Batavia, before being transferred (possibly via Changi) to the Thai-Burma Railway .

The brutality in both camps is beyond description. The prisoners witnessed horrors unimagineable, endured beatings and torture, suffered starvation and disease. There are numerous accounts of the conduct of these camps - I’d recommend two in particular: The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop, and Sandakan: A Conspiracy of Silence by Lynette Ramsay Silver. The illustrations of Jack Chalker also paint a vivid picture of the conditions and treatment of the humanity (and lack of it) on the Thai-Burma Railway in particular. After reading these, you are left in no doubt that Mankind has the capacity for great evil - but also an endless capacity for selflessness and courage. And endurance.

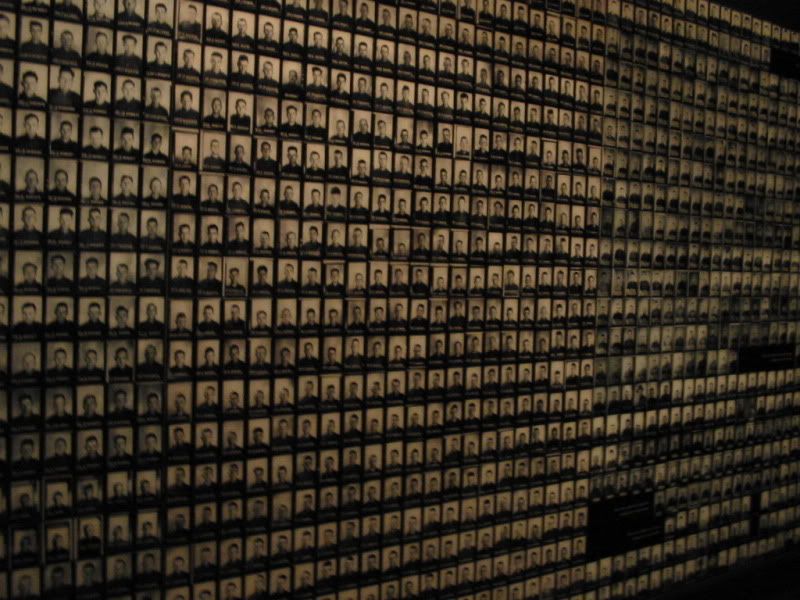

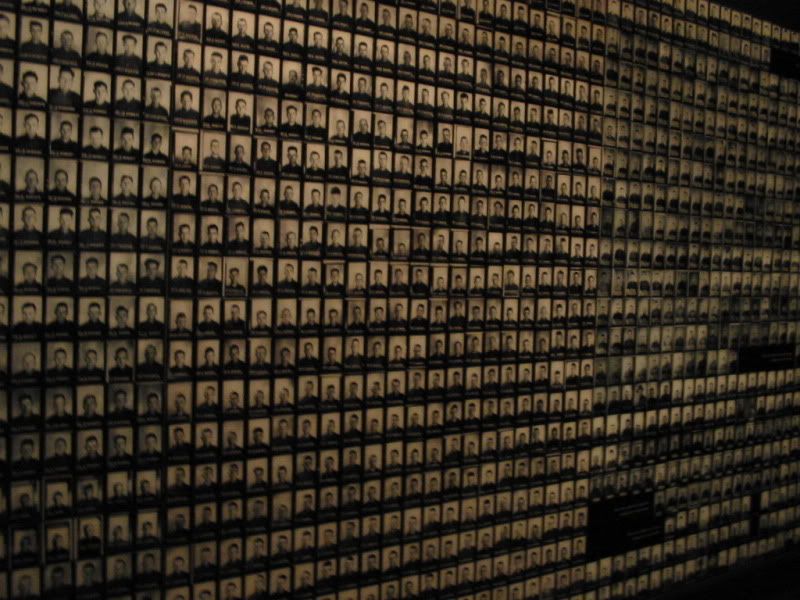

To give some idea of the scale of loss at Sandakan, the Australian War Memorial has established a permanent memorial:

Each tiny paybook image is the size of a passport photo, and there are thousands of them. They take up the whole wall of a quiet, dim alcove, and you can sit and reflect on the whole pointless waste of so much life.

Did the brothers know what had happened to each other? It can only be speculated, but there are points of cross-over. Some of Jack’s company ended up on the Thai-Burma Railway. Two of the HMAS Perth survivors (AB George Morriss, and HA Kelly) ended up in Sandakan. Did they speak to Jack? Did the brothers know what had happened to each other?

And the family - how long did they have to wait for news? It was months before it was confirmed that the boys were ‘Missing’, further long months before they knew the boys were prisoners-of-war - how long did they hold out hope that the boys would one day come home?

Chicka died on 21 February 1944, aged 24, of dysentery and bronchial pneumonia.

In Sandakan, Jack deteriorated until he was too ill to walk. As a result he was one of the 288 left behind when the Japanese commenced the forced marches to Ranau. He was left behind to starve to death. He died on 3 June 1945, aged 28,

Chicka is buried in the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, Thailand. Jack has no known grave, he’s commemorated on a panel (24) at the Labuan Memorial Cemetery in Borneo.

These are the bare facts, the stark facts. For years these sufficed - who would wish to know more beyond your son, your brother, your sweetheart wasn’t coming home? In many ways it needs time for the edges to soften, and it needs someone like me - of, and yet not of, this family - to start to ask the sometimes uncomfortable questions , to search and try to find out the story between the lines.

It is a story that must not be forgotten. These two young men must not be forgotten. These two of so many men, that we are remembering today, on Anzac Day.

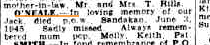

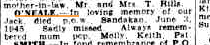

The lack of information does not mean that there was a lack of grief - far from it. The grief was deep and it was enduring. For years afterwards, on the anniversary of each of the boys’ deaths, a notice appeared in the In Memoriam section of the Sydney Morning Herald. Almost lost amongst many similar notices, commemorating those lost on active service, these brief words speak of the heartbreak of a mother, of a family, whose home would never be the same again.

This is only the beginning of the story for me. I have begun researching in earnest, and in time hope to be able to answer the many, many questions I have. There are so many gaps, so little specific information about the boys’ experiences. One day I’ll tell the tale properly.

As far as I can establish, all the boys (five of the six children) attended school at Christian Brothers Lewisham. As the boys grew up, and left school they moved into the workforce: Lionel worked in a factory, Jack was a compositor, working for the Australian Medical Publishing Company; next boy down, Christopher (known as Chicka) was also a compositor (machine mechanic), and the twins, Paddy and Keith (‘Mick’) eventually entered the NSW Public Service.

We have no letters from them, no photographs or other physical mementoes. Who knows where these things vanished to over the past 70 years! (How easy is it for all traces of someone to disappear...) Speaking with those that do have some recollections of them, we know that Jack was an athletic young man, a competitive boxer. He’s been described to me as good looking, with blue eyes. Also, apparently, something of a hero to the younger boys. Chicka was also fair with blue eyes, and a very gentle soul. Both were about 5’8” tall, Jack possibly just about a half inch taller.

With war clouds gathering, in January 1939 Jack enlisted in the Militia Forces (the Reserves); Chicka joined the Navy in March 1939, and reported for duty post-mobilisation at HMAS Penguin on 26 August 1939. Just in time for the outbreak of the Second World War. He was just 19.

Once training was completed, Chicka did a number of stints on various vessels, before being promoted to Able Seaman and transferred to the HMAS Perth on 1 July 1941.

Jack, in the meantime, had been called up, and taken his oath of enlistment at Victoria Barracks in Paddington (in Sydney) on 10 July 1940. He spent time with a number of different battalions, before being transferred to the 2/3 Reserve Motor Transport Company in March 1941.

On 10 April 1941, Jack embarked for Singapore onboard HMT 26 (‘Orcades’), arriving 24 April 1941, just the day before Anzac Day.

Once in Singapore, Jack served along the Malay Peninsula, before being caught up in the chaotic withdrawal back, back, back...and then the eventual capitulation to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. The next record we have is from Changi, and then on 8 July 1942 he embarked as part of ‘B’ Force on the Ubi Maru to Borneo. To the Sandakan Prisoner of War Camp.

The Perth was undergoing a refit at the time Chicka joined it, (it spent time in the Fitzroy Dock at Cockatoo Island - which I can see from my living room window). Following exercises off the coast, the ship left Australia for Java on 14 February 1942, arriving on 24 February 1942.

He survived the sinking of the Perth in the Sunda Straits, and the next record indicates that he was imprisoned in the so-called’Bicycle Camp’ in Batavia, before being transferred (possibly via Changi) to the Thai-Burma Railway .

The brutality in both camps is beyond description. The prisoners witnessed horrors unimagineable, endured beatings and torture, suffered starvation and disease. There are numerous accounts of the conduct of these camps - I’d recommend two in particular: The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop, and Sandakan: A Conspiracy of Silence by Lynette Ramsay Silver. The illustrations of Jack Chalker also paint a vivid picture of the conditions and treatment of the humanity (and lack of it) on the Thai-Burma Railway in particular. After reading these, you are left in no doubt that Mankind has the capacity for great evil - but also an endless capacity for selflessness and courage. And endurance.

To give some idea of the scale of loss at Sandakan, the Australian War Memorial has established a permanent memorial:

Each tiny paybook image is the size of a passport photo, and there are thousands of them. They take up the whole wall of a quiet, dim alcove, and you can sit and reflect on the whole pointless waste of so much life.

Did the brothers know what had happened to each other? It can only be speculated, but there are points of cross-over. Some of Jack’s company ended up on the Thai-Burma Railway. Two of the HMAS Perth survivors (AB George Morriss, and HA Kelly) ended up in Sandakan. Did they speak to Jack? Did the brothers know what had happened to each other?

And the family - how long did they have to wait for news? It was months before it was confirmed that the boys were ‘Missing’, further long months before they knew the boys were prisoners-of-war - how long did they hold out hope that the boys would one day come home?

Chicka died on 21 February 1944, aged 24, of dysentery and bronchial pneumonia.

In Sandakan, Jack deteriorated until he was too ill to walk. As a result he was one of the 288 left behind when the Japanese commenced the forced marches to Ranau. He was left behind to starve to death. He died on 3 June 1945, aged 28,

Chicka is buried in the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, Thailand. Jack has no known grave, he’s commemorated on a panel (24) at the Labuan Memorial Cemetery in Borneo.

These are the bare facts, the stark facts. For years these sufficed - who would wish to know more beyond your son, your brother, your sweetheart wasn’t coming home? In many ways it needs time for the edges to soften, and it needs someone like me - of, and yet not of, this family - to start to ask the sometimes uncomfortable questions , to search and try to find out the story between the lines.

It is a story that must not be forgotten. These two young men must not be forgotten. These two of so many men, that we are remembering today, on Anzac Day.

The lack of information does not mean that there was a lack of grief - far from it. The grief was deep and it was enduring. For years afterwards, on the anniversary of each of the boys’ deaths, a notice appeared in the In Memoriam section of the Sydney Morning Herald. Almost lost amongst many similar notices, commemorating those lost on active service, these brief words speak of the heartbreak of a mother, of a family, whose home would never be the same again.

This is only the beginning of the story for me. I have begun researching in earnest, and in time hope to be able to answer the many, many questions I have. There are so many gaps, so little specific information about the boys’ experiences. One day I’ll tell the tale properly.