Did you think I died?

LOL - so, I'm MIA more often than not and the "daily doozies" have become more of an annual thing. My apologies. RL is what it is, fandom (my teeny little corner) is what it is (not what it was). I'm not reading as much in fandom and what I do read is pretty good and has little to set off a doozie, so.... excuses, excuses. As you may or may not know, RL, now that I've retired from going to work at a school everyday, consists of catching up on twenty years of neglect of yard and house (very much still a wip) and a "part-time" job as a copy and submissions editor for a niche publishing company that is growing by leaps and bounds. The result is that I spend a lot of time reading, and a lot of time thinking about writing, grammar, punctuation, etc. but have little time left over for my own writing (admittedly somewhat influenced by having been writing the same characters for so many years I'm running out of steam) and even less time to think about things like this community.

I'm not leaving it - which is probably how it sounds - just explaining why you rarely see a post anymore. It is a community, though, and any member is welcome to share things with everyone. Doesn't need to be just me. :)

Anyway, in the interest of proving I'm not dead, I want to share this excellent blog entry about working with and around all those "never do this or that" rules that you see given out freely by everyone from actual successful writers to creative writing teachers. This sums up really well that, as important as rules are, knowing how and when to make an exception can set you apart from everyone else who is learning to write. Rules are good, and important to know, but a slavish devotion to any one person's opinion of how you should express yourself is not going to work out well in the long run (unless you are trying to appear to be a clone of said "authority". Here is the text, the link to the blog is below. Enjoy!

(Almost) Never Say Never

Never begin a sentence with a coordinating conjunction.

Never end a sentence with a preposition.

Never write a book based on current trends.

Never continue to work on a story that isn’t working.

Never ignore the fundamental basics of good story writing: grammar, spelling, punctuation, character and plot development, compelling content, good flow, realistic dialogue, etc.

Never try to emulate someone else’s style.

Never use clichés.

Never start a story with dialogue, weather, excessive narrative or description, a dream, a ringing alarm or cell phone, a prologue, backstory, an information dump, lots of telling and no showing, and the prohibitions go on and on.

Yikes! I’ve already opted to mop the kitchen floor on my hands and knees instead of write-and I

have a bad knee. Wait! Exceptions exist to every rule, right? Make that almost every rule. (Don’t try defying gravity unless you have a parachute.)

Back to books. Starting a sentence with a coordinating conjunction isn’t a great idea, but it’s effective in an intense scene where power sentences must be short. Beginning the next sentence with “and” or “but” gives you a connection and a punch that could be lost by making the previous one longer.

Never ending a sentence with a preposition is an old rule that long ago fell into disfavor. Breaking this one will not likely violate any agent’s taboos.

Current trends are just that-current. By the time you get your story written, rewritten, edited, proofed, laid out, and published, the trend will probably be on death row. New twists on timeless themes are winners; they’re not here today and gone tomorrow.

Never continue a story that isn’t coming together-good rule. If a story isn’t working, shelve it. Maybe you can breathe new life into it later, but move on now.

Grammar and punctuation rules have one objective: clarity. That should be sufficient incentive to obey them unless you have a valid reason for not doing so and know when and how to break them-then don’t make it a habit. Correct spelling? That’s a given. Character and plot development are the foundations of story; don’t shortchange yourself or your book here. Stories need good flow in addition to compelling content to keep the reader turning pages. A reader who has to go back to figure out what's happening is a reader who probably won’t buy your next book; in fact, he/she may not finish this one. Writing great dialogue is an art. Study it. Learn it. An otherwise fantastic story can fall flat if conversation (with others or internal) isn’t “real.” People often don’t talk in complete sentences, speak grammatically, avoid slang, etc. Keep this in mind as you write.

Your own style and voice will set you apart from the myriad writers vying for readers. Develop those qualities. Hone them. Create your “signature.” Make your book your calling card, uniquely and magnificently your own.

Clichés-overused and abused sayings that most editors insist on deleting-can sometimes have a place in stories. A great-aunt, grandfather, or distant cousin from the backwoods may naturally include them as part of his/her speech pattern. A cliché tweaked to fit a character or scene can work well when it’s personalized to fit the story, and it infuses new life into a tired, old saying. Again, avoid excessive use.

Start your story in a compelling way; that is, compel your reader to keep reading. Dialogue? Weather? Description? Dream? Ringing whatever? Prologue? If these are done right, are short and to the point, are relevant to the story, and grip the reader, use them freely but wisely. Backstory? Working it seamlessly into your developing tale as needed is far more effective than overwhelming the reader with it in the first chapter. Information dump? Almost always a “never.” Telling rather than showing? Some telling is inevitable, but keep it in check. Remember that you need to hook your

reader on the first page, ideally in the first paragraph, and cultivate that interest all the way to the end. This is the rule that counts. Most of the others can be broken-occasionally and correctly, that is.

Too many rules imprison creativity. Great writing doesn’t result from driving ourselves crazy in an effort to obey every writing rule we know. It comes from learning how to construct an effective story, letting creative juices flow, understanding rules, and applying those that will turn a good story into an extraordinary read.

How do you feel about the “never” rules? Which ones are better broken? What unmentioned rules have challenged you when beginning a new story? Why do you believe rules should or should not govern our writing?

Find it here

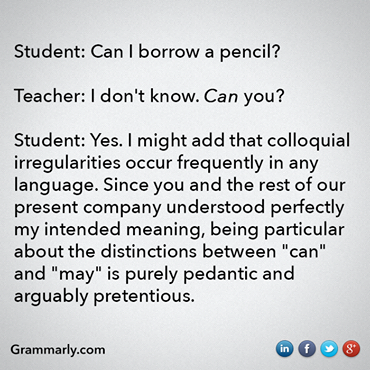

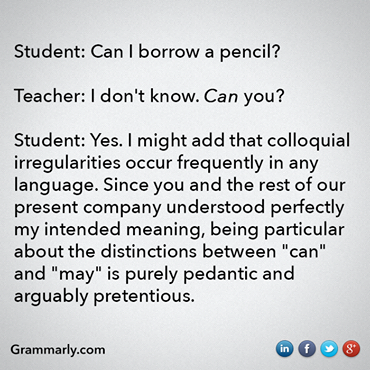

ETA: Just for fun:

I'm not leaving it - which is probably how it sounds - just explaining why you rarely see a post anymore. It is a community, though, and any member is welcome to share things with everyone. Doesn't need to be just me. :)

Anyway, in the interest of proving I'm not dead, I want to share this excellent blog entry about working with and around all those "never do this or that" rules that you see given out freely by everyone from actual successful writers to creative writing teachers. This sums up really well that, as important as rules are, knowing how and when to make an exception can set you apart from everyone else who is learning to write. Rules are good, and important to know, but a slavish devotion to any one person's opinion of how you should express yourself is not going to work out well in the long run (unless you are trying to appear to be a clone of said "authority". Here is the text, the link to the blog is below. Enjoy!

(Almost) Never Say Never

Never begin a sentence with a coordinating conjunction.

Never end a sentence with a preposition.

Never write a book based on current trends.

Never continue to work on a story that isn’t working.

Never ignore the fundamental basics of good story writing: grammar, spelling, punctuation, character and plot development, compelling content, good flow, realistic dialogue, etc.

Never try to emulate someone else’s style.

Never use clichés.

Never start a story with dialogue, weather, excessive narrative or description, a dream, a ringing alarm or cell phone, a prologue, backstory, an information dump, lots of telling and no showing, and the prohibitions go on and on.

Yikes! I’ve already opted to mop the kitchen floor on my hands and knees instead of write-and I

have a bad knee. Wait! Exceptions exist to every rule, right? Make that almost every rule. (Don’t try defying gravity unless you have a parachute.)

Back to books. Starting a sentence with a coordinating conjunction isn’t a great idea, but it’s effective in an intense scene where power sentences must be short. Beginning the next sentence with “and” or “but” gives you a connection and a punch that could be lost by making the previous one longer.

Never ending a sentence with a preposition is an old rule that long ago fell into disfavor. Breaking this one will not likely violate any agent’s taboos.

Current trends are just that-current. By the time you get your story written, rewritten, edited, proofed, laid out, and published, the trend will probably be on death row. New twists on timeless themes are winners; they’re not here today and gone tomorrow.

Never continue a story that isn’t coming together-good rule. If a story isn’t working, shelve it. Maybe you can breathe new life into it later, but move on now.

Grammar and punctuation rules have one objective: clarity. That should be sufficient incentive to obey them unless you have a valid reason for not doing so and know when and how to break them-then don’t make it a habit. Correct spelling? That’s a given. Character and plot development are the foundations of story; don’t shortchange yourself or your book here. Stories need good flow in addition to compelling content to keep the reader turning pages. A reader who has to go back to figure out what's happening is a reader who probably won’t buy your next book; in fact, he/she may not finish this one. Writing great dialogue is an art. Study it. Learn it. An otherwise fantastic story can fall flat if conversation (with others or internal) isn’t “real.” People often don’t talk in complete sentences, speak grammatically, avoid slang, etc. Keep this in mind as you write.

Your own style and voice will set you apart from the myriad writers vying for readers. Develop those qualities. Hone them. Create your “signature.” Make your book your calling card, uniquely and magnificently your own.

Clichés-overused and abused sayings that most editors insist on deleting-can sometimes have a place in stories. A great-aunt, grandfather, or distant cousin from the backwoods may naturally include them as part of his/her speech pattern. A cliché tweaked to fit a character or scene can work well when it’s personalized to fit the story, and it infuses new life into a tired, old saying. Again, avoid excessive use.

Start your story in a compelling way; that is, compel your reader to keep reading. Dialogue? Weather? Description? Dream? Ringing whatever? Prologue? If these are done right, are short and to the point, are relevant to the story, and grip the reader, use them freely but wisely. Backstory? Working it seamlessly into your developing tale as needed is far more effective than overwhelming the reader with it in the first chapter. Information dump? Almost always a “never.” Telling rather than showing? Some telling is inevitable, but keep it in check. Remember that you need to hook your

reader on the first page, ideally in the first paragraph, and cultivate that interest all the way to the end. This is the rule that counts. Most of the others can be broken-occasionally and correctly, that is.

Too many rules imprison creativity. Great writing doesn’t result from driving ourselves crazy in an effort to obey every writing rule we know. It comes from learning how to construct an effective story, letting creative juices flow, understanding rules, and applying those that will turn a good story into an extraordinary read.

How do you feel about the “never” rules? Which ones are better broken? What unmentioned rules have challenged you when beginning a new story? Why do you believe rules should or should not govern our writing?

Find it here

ETA: Just for fun: