Robots Ready to Take Over World Economy.

First Robot to Become President Will Break Glass Ceiling.

Black Americans Are Working More-With Little to Show for It

Despite working more every year, earnings gaps aren’t improving.

The discrepancies in earnings, wealth and other markers of financial success between black and white Americans are stark. Black Americans, for instance hold much less wealth and have higher rates of unemployment. But perhaps more unsettling than the gaps themselves is the fact that even as many black Americans make progress that should help bridge the divide, such as by working more hours, they have yet to see tangible or enduring economic advancement.

Valerie Wilson and Janelle Jones, economists at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, took a look at labor data for black and white workers between the years 1979 and 2015. They found that both black and white workers, between 18 and 64 years old, have increased their number of paid, annual hours of work in the past 36 years. According to the analysis by Wilson and Jones, the average black worker in 2015 put in 1,805 hours, or 12.4 percent more hours than they did in 1979. By contrast, the average white worker put in 1,888 hours, for an increase of around 11 percent. While those trajectories may seem similar, the picture looks a lot different when it comes to the lowest-wage workers in each racial group. When looking at the lowest earners, black workers have seen much more significant increases.

In both 1979 and 2015, poor black Americans worked more hours than poor white Americans. The poorest black workers have increased their annual hours of work to 1,524, a gain of 22 percent from 1979, compared to the 1,445 hours and 17 percent gain of white workers, according to EPI. Unsurprisingly, in both groups, women had the largest gains when it comes to the number of hours worked, in part because more women entered the workforce. But low-wage black women in particular have seen the largest increase in the amount they work each year of any racial, gender, or income- group combination, logging 30 percent more time on the job since 1979.

With the increased hours of labor and climbing education levels, it would stand to reason that black workers in 2015 were in a better economic position than they were in 1979-but that’s not really true. Black-white wage gaps are actually larger now than they were in 1979. The growing discrepancy is even more pronounced for the same low-income workers who are adding the most work hours. In 1979, white workers in the bottom 10 percent of earners made 3.6 percent more than black workers in the lowest income bracket. In 2015, the poorest white workers made 11.8 percent more.

Wilson and Jones say that these gains rebut critics who “blame black workers for racial wage gaps, saying that they should do anything, from getting more education to simply working harder.” Those arguments, they write, ignore the impact of racial discrimination in the labor market and perpetuate stereotypes about the work ethic of black Americans that aren’t supported by data.

For all black workers, bridging economic gaps is proving difficult. Though unemployment numbers have improved across the board, the same discrepancies persist: white Americans had an unemployment rate of only 4.5 percent at the close of 2016, but black workers had an unemployment rate of 7.9 percent. (That’s actually a relatively small gap considering that, historically, the unemployment rate among black Americans have been around double that for white Americans.)

The racial wealth gap has also widened since the Great Recession, according to Pew Research. In 2004, white families held about seven times as much wealth as black families; by 2013, that ratio had grown to 13. And economic downturns such as the Great Recession have long hit black families harder than white ones; the Economic Policy Institute observed similar effects after both the 2001 and 1990 recessions. Over time, these differences only grow: A report from the American Civil Liberties Union looking at the long-term effects of the Great Recession found that by 2031, white families will have wealth that is 31 percent lower due to losses in the recession, while Black families will have 40 percent less of their already lower wealth.

There’s reason to be concerned about these inequalities going forward. Not only do black Americans, especially poor ones, not have enough wealth to weather a shock, but they are also unemployed at higher rates. And when they do find jobs, they are often paid less and scrutinized more. The result is a cycle of economic disadvantage that’s hard to break.

Black Americans Are Working More-With Little to Show for It

How Many Jobs Do Robots Destroy? Answers Emerge

But this isn’t the industrial revolution.

How many jobs do robots - whether mechanical robots or software - destroy? Do these destroyed jobs get replaced by the Great American Economy with better jobs? That’s the big discussion these days.

The answers have been soothing. Economists cite the industrial revolution. At the time, most humans replaced by machines found better paid, more productive, less back-breaking jobs. Productivity soared, and society overall, after some big dislocations, came out ahead. The same principle applies today, the soothsayers coo.

But this isn’t the industrial revolution. These days, robots and algorithms are everywhere, replacing not just manufacturing jobs but all kinds jobs in air-conditioned offices that paid big salaries and fat bonuses.

Just today, BlackRock announced a plan to consolidate $30 billion of their actively managed mutual fund activities with funds that are managed by algorithms and quantitative models. As these software robots take over, “53 stock pickers are expected to step down from their funds. Dozens more are expected to leave the firm,” as the New York Times put it.

“We have to change the ecosystem - that means relying more on big data, artificial intelligence, factors and models within quant and traditional investment strategies,” BlackRock CEO Laurence Fink told The Times.

In a similar vein, “robo-advisors” are becoming a cheap and hot alternative for many customers at major brokerage houses, replacing human financial advisors. A lot of the grunt work that used to be done during all-nighters by highly paid law school grads in big law offices is now done by computers.

So job destruction due to automation is not a blue-collar thing anymore. It’s everywhere. But soothsayers have been steadfastly claiming that for each destroyed job, the Great American Economy will generate more and better jobs, because, well, that’s how it worked during, you guessed it, the Industrial Revolution.

But two economists have changed their mind (more on that in a moment) and published a gloomy working paper.

Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo studied how the increase of industrial robots between 1990 through 2007 has impacted US jobs and wages. They found “large and robust negative effects of robots on employment and wages across commuting zones.”

Their working paper is available at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). This is the organization that is responsible for tracking US business cycles and calling “recessions.”

There are two effects of robots, the authors point out: The “displacement effect” when robots eliminate jobs; and the “productivity effect” as other industries or tasks require more labor and thus create jobs (for example, designing, making, and maintaining robots). But these productivity effects no longer suffice to compensate for jobs that industrial robots destroyed.

Specifically, they found that in a “commuting zone” with exposure to robots versus a “commuting zone” without exposure to robots:

In 2014, there were 1.7 robots per 1,000 workers in the US, up from about 0.7 in 2000. Auto manufacturing is the leader in the use of industrial robots. Other sectors include electronics, metal products, plastics, and chemicals.

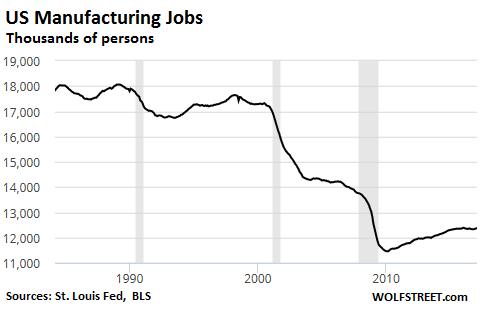

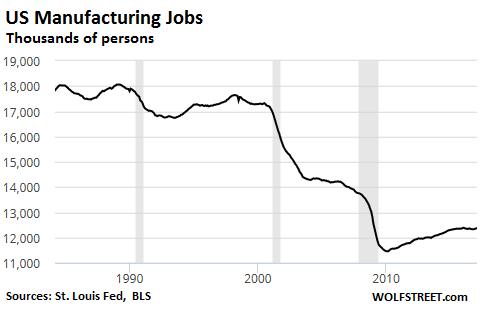

Between 1990 and 2007, industrial robots have eliminated a net of 670,000 jobs, according to the study. For perspective, this chart shows the total number of employees in manufacturing, which dropped by 36% from the peak of 19.5 million in 1979 to 12.4 million in February:

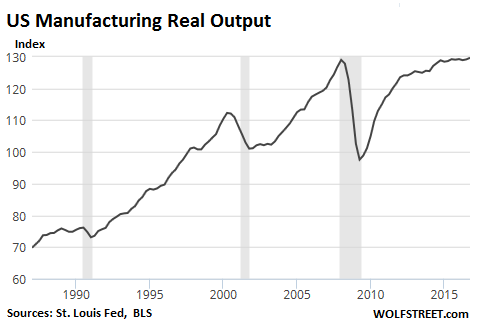

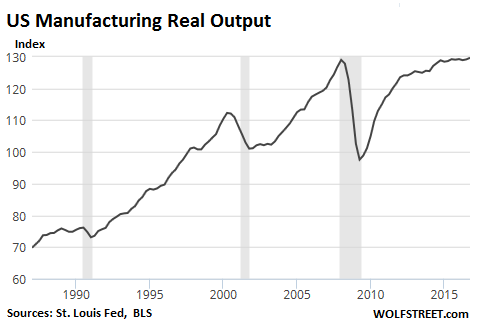

However, manufacturing output, adjusted for inflation, soared due to automation until 2007. During the Great Recession, output crashed. Now it has finally edged past its prior peak:

The number of industrial robots in the US is expected to quadruple. So job losses in manufacturing will continue, even if output rises.

The authors were once in the opposite camp but now have changed their mind about net job destruction by robots. The New York Times:

The paper is all the more significant because the researchers, whose work is highly regarded in their field, had been more sanguine about the effect of technology on jobs. In a paper last year, they said it was likely that increased automation would create new, better jobs, so employment and wages would eventually return to their previous levels. Just as cranes replaced dockworkers but created related jobs for engineers and financiers, the theory goes, new technology has created new jobs for software developers and data analysts.

But that paper was a conceptual exercise. The new one uses real-world data - and suggests a more pessimistic future.

The researchers said they were surprised to see very little employment increase in other occupations to offset the job losses in manufacturing. That increase could still happen, they said, but for now there are large numbers of people out of work, with no clear path forward - especially blue-collar men without college degrees.

But industrial robots are the great equalizer. They reduce the importance of wage differences, for example between the US and a cheap-labor country like China: Unlike labor, robots cost the same everywhere.

China is now on the forefront of robotizing its manufacturing plants, as wages have been soaring for years. In doing so, China is gradually losing its advantage as a low-wage country. In this scenario, manufacturing in the US can be competitive with China, particularly after figuring in the costs of transportation, time delays, risks of all kinds, and the like. So manufacturing could actually grow again in the US, but the jobs won’t come back.

And auto manufacturers face some challenges. Last time they tried this was in 2009! Read… Automakers Resorts to Biggest Incentives Ever Just to Slow the Decline in Sales

How Many Jobs Do Robots Destroy? Answers Emerge

Robots v experts: are any human professions safe from automation?

Technology already outperforms humans in many areas, but surely we would never accept machines as teachers, doctors or judges? Don’t be so sure

The main themes of our book, The Future of the Professions, can be put simply: machines are becoming increasingly capable and so are taking on more and more tasks.

Many of these tasks were once the exclusive preserve of human professionals such as doctors, lawyers and accountants. While new tasks will certainly emerge in years to come, it is probable that machines will, over time, take on many of these as well. In the 2020s, we say, this will not mean unemployment, but rather a need for widespread retraining and redeployment. In the long run though, we find it hard to avoid the conclusion that there will be a steady decline in the need for traditional professional workers.

During the year after the book’s hardback publication in October 2015, we tested this line of argument on audiences of professionals in more than 20 countries, speaking to around 15,000 people at over 100 events. The response, frankly, was mixed. Our work seems to polarise people into those who agree zealously with our thesis, and those who reject it unreservedly. Both sides argue their views passionately.

This divide corresponds largely with current views on AI: some argue that we are entering an entirely new epoch, while others dismiss this as hype, maintaining that we have been through similar transitions before. We have found that accountants are usually receptive, lawyers are largely conservative and journalists seem to be resigned. Teachers are either sceptical or evangelical, doctors tend to dismiss the idea of non-doctors having a view on their future, architects express considerable interest in new ways of working, management consultants see more scope for change in other professions than in their own, and the clergy have been more or less silent.

In light of feedback and our more recent research, do we still really think that one day we will no longer need our trusted advisers? Is it not obvious, we are often asked to admit, that human beings will always want a face-to-face, that we will surely crave the reassurance that a warm, empathetic person can afford a fellow human being?

We have never denied the significance of the great comfort that one person can give another. Indeed, we go further - in our book, we explicitly identify the “empathiser” as an important role in the future. Nonetheless, our experience - as researchers and advisers to the professions - suggests that many recipients of professional service are actually looking for a reliable solution or outcome, rather than a trusted adviser per se.

Fast-forward a few years, to a time when the level of output of, for example, an online medical or legal service is very high and its branding is beyond reproach. This of itself will offer its own level of comfort and reassurance. In many circumstances, this will be enough for patients and clients, and will be consistently more affordable than the empathetic adviser. Understandably, many professionals remain deeply sceptical, and want to insist that there will always be tasks for which humans are better suited than machines.

But there is a danger of being excessively human-centric. In contemplating the potential of future machines to outperform professionals, what really matters is not how the systems operate but whether, in terms of the outcome, the end product is superior. In other words, whether or not machines will replace human professionals is not down to the capacity of systems to perform tasks as people do. It is whether systems can out-perform human beings. And in many fields, they already can.

Extract

Scepticism about the role of machines is perhaps most compelling when expressed in human terms - when, for example, it is asserted that, “of course, machines will never actually think or have feelings or have a craftsman’s sense of touch, or decide what is the right thing to do”. Framed in this way, this sort of claim appears convincing. It is indeed hard to imagine a machine thinking with the clarity of a judge, empathising in the manner of a psychoanalyst, extracting a molar with the dexterity of a dental surgeon, or taking a view on the ethics of a tax-avoidance scheme.

Robots v experts: are any human professions safe from automation?

Black Americans Are Working More-With Little to Show for It

Despite working more every year, earnings gaps aren’t improving.

The discrepancies in earnings, wealth and other markers of financial success between black and white Americans are stark. Black Americans, for instance hold much less wealth and have higher rates of unemployment. But perhaps more unsettling than the gaps themselves is the fact that even as many black Americans make progress that should help bridge the divide, such as by working more hours, they have yet to see tangible or enduring economic advancement.

Valerie Wilson and Janelle Jones, economists at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, took a look at labor data for black and white workers between the years 1979 and 2015. They found that both black and white workers, between 18 and 64 years old, have increased their number of paid, annual hours of work in the past 36 years. According to the analysis by Wilson and Jones, the average black worker in 2015 put in 1,805 hours, or 12.4 percent more hours than they did in 1979. By contrast, the average white worker put in 1,888 hours, for an increase of around 11 percent. While those trajectories may seem similar, the picture looks a lot different when it comes to the lowest-wage workers in each racial group. When looking at the lowest earners, black workers have seen much more significant increases.

In both 1979 and 2015, poor black Americans worked more hours than poor white Americans. The poorest black workers have increased their annual hours of work to 1,524, a gain of 22 percent from 1979, compared to the 1,445 hours and 17 percent gain of white workers, according to EPI. Unsurprisingly, in both groups, women had the largest gains when it comes to the number of hours worked, in part because more women entered the workforce. But low-wage black women in particular have seen the largest increase in the amount they work each year of any racial, gender, or income- group combination, logging 30 percent more time on the job since 1979.

With the increased hours of labor and climbing education levels, it would stand to reason that black workers in 2015 were in a better economic position than they were in 1979-but that’s not really true. Black-white wage gaps are actually larger now than they were in 1979. The growing discrepancy is even more pronounced for the same low-income workers who are adding the most work hours. In 1979, white workers in the bottom 10 percent of earners made 3.6 percent more than black workers in the lowest income bracket. In 2015, the poorest white workers made 11.8 percent more.

Wilson and Jones say that these gains rebut critics who “blame black workers for racial wage gaps, saying that they should do anything, from getting more education to simply working harder.” Those arguments, they write, ignore the impact of racial discrimination in the labor market and perpetuate stereotypes about the work ethic of black Americans that aren’t supported by data.

For all black workers, bridging economic gaps is proving difficult. Though unemployment numbers have improved across the board, the same discrepancies persist: white Americans had an unemployment rate of only 4.5 percent at the close of 2016, but black workers had an unemployment rate of 7.9 percent. (That’s actually a relatively small gap considering that, historically, the unemployment rate among black Americans have been around double that for white Americans.)

The racial wealth gap has also widened since the Great Recession, according to Pew Research. In 2004, white families held about seven times as much wealth as black families; by 2013, that ratio had grown to 13. And economic downturns such as the Great Recession have long hit black families harder than white ones; the Economic Policy Institute observed similar effects after both the 2001 and 1990 recessions. Over time, these differences only grow: A report from the American Civil Liberties Union looking at the long-term effects of the Great Recession found that by 2031, white families will have wealth that is 31 percent lower due to losses in the recession, while Black families will have 40 percent less of their already lower wealth.

There’s reason to be concerned about these inequalities going forward. Not only do black Americans, especially poor ones, not have enough wealth to weather a shock, but they are also unemployed at higher rates. And when they do find jobs, they are often paid less and scrutinized more. The result is a cycle of economic disadvantage that’s hard to break.

Black Americans Are Working More-With Little to Show for It

How Many Jobs Do Robots Destroy? Answers Emerge

But this isn’t the industrial revolution.

How many jobs do robots - whether mechanical robots or software - destroy? Do these destroyed jobs get replaced by the Great American Economy with better jobs? That’s the big discussion these days.

The answers have been soothing. Economists cite the industrial revolution. At the time, most humans replaced by machines found better paid, more productive, less back-breaking jobs. Productivity soared, and society overall, after some big dislocations, came out ahead. The same principle applies today, the soothsayers coo.

But this isn’t the industrial revolution. These days, robots and algorithms are everywhere, replacing not just manufacturing jobs but all kinds jobs in air-conditioned offices that paid big salaries and fat bonuses.

Just today, BlackRock announced a plan to consolidate $30 billion of their actively managed mutual fund activities with funds that are managed by algorithms and quantitative models. As these software robots take over, “53 stock pickers are expected to step down from their funds. Dozens more are expected to leave the firm,” as the New York Times put it.

“We have to change the ecosystem - that means relying more on big data, artificial intelligence, factors and models within quant and traditional investment strategies,” BlackRock CEO Laurence Fink told The Times.

In a similar vein, “robo-advisors” are becoming a cheap and hot alternative for many customers at major brokerage houses, replacing human financial advisors. A lot of the grunt work that used to be done during all-nighters by highly paid law school grads in big law offices is now done by computers.

So job destruction due to automation is not a blue-collar thing anymore. It’s everywhere. But soothsayers have been steadfastly claiming that for each destroyed job, the Great American Economy will generate more and better jobs, because, well, that’s how it worked during, you guessed it, the Industrial Revolution.

But two economists have changed their mind (more on that in a moment) and published a gloomy working paper.

Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo studied how the increase of industrial robots between 1990 through 2007 has impacted US jobs and wages. They found “large and robust negative effects of robots on employment and wages across commuting zones.”

Their working paper is available at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). This is the organization that is responsible for tracking US business cycles and calling “recessions.”

There are two effects of robots, the authors point out: The “displacement effect” when robots eliminate jobs; and the “productivity effect” as other industries or tasks require more labor and thus create jobs (for example, designing, making, and maintaining robots). But these productivity effects no longer suffice to compensate for jobs that industrial robots destroyed.

Specifically, they found that in a “commuting zone” with exposure to robots versus a “commuting zone” without exposure to robots:

- Each additional robot reduces employment by a net of 6.2 workers.

- Each additional robot per 1,000 workers reduces average wages by 0.73%.

- One more robot per thousand workers reduces the US employment-to-population ratio by about 0.18-0.34 percentage points.

- One more robot per thousand workers reduces US wages by 0.25% to 0.5%.

In 2014, there were 1.7 robots per 1,000 workers in the US, up from about 0.7 in 2000. Auto manufacturing is the leader in the use of industrial robots. Other sectors include electronics, metal products, plastics, and chemicals.

Between 1990 and 2007, industrial robots have eliminated a net of 670,000 jobs, according to the study. For perspective, this chart shows the total number of employees in manufacturing, which dropped by 36% from the peak of 19.5 million in 1979 to 12.4 million in February:

However, manufacturing output, adjusted for inflation, soared due to automation until 2007. During the Great Recession, output crashed. Now it has finally edged past its prior peak:

The number of industrial robots in the US is expected to quadruple. So job losses in manufacturing will continue, even if output rises.

The authors were once in the opposite camp but now have changed their mind about net job destruction by robots. The New York Times:

The paper is all the more significant because the researchers, whose work is highly regarded in their field, had been more sanguine about the effect of technology on jobs. In a paper last year, they said it was likely that increased automation would create new, better jobs, so employment and wages would eventually return to their previous levels. Just as cranes replaced dockworkers but created related jobs for engineers and financiers, the theory goes, new technology has created new jobs for software developers and data analysts.

But that paper was a conceptual exercise. The new one uses real-world data - and suggests a more pessimistic future.

The researchers said they were surprised to see very little employment increase in other occupations to offset the job losses in manufacturing. That increase could still happen, they said, but for now there are large numbers of people out of work, with no clear path forward - especially blue-collar men without college degrees.

But industrial robots are the great equalizer. They reduce the importance of wage differences, for example between the US and a cheap-labor country like China: Unlike labor, robots cost the same everywhere.

China is now on the forefront of robotizing its manufacturing plants, as wages have been soaring for years. In doing so, China is gradually losing its advantage as a low-wage country. In this scenario, manufacturing in the US can be competitive with China, particularly after figuring in the costs of transportation, time delays, risks of all kinds, and the like. So manufacturing could actually grow again in the US, but the jobs won’t come back.

And auto manufacturers face some challenges. Last time they tried this was in 2009! Read… Automakers Resorts to Biggest Incentives Ever Just to Slow the Decline in Sales

How Many Jobs Do Robots Destroy? Answers Emerge

Robots v experts: are any human professions safe from automation?

Technology already outperforms humans in many areas, but surely we would never accept machines as teachers, doctors or judges? Don’t be so sure

The main themes of our book, The Future of the Professions, can be put simply: machines are becoming increasingly capable and so are taking on more and more tasks.

Many of these tasks were once the exclusive preserve of human professionals such as doctors, lawyers and accountants. While new tasks will certainly emerge in years to come, it is probable that machines will, over time, take on many of these as well. In the 2020s, we say, this will not mean unemployment, but rather a need for widespread retraining and redeployment. In the long run though, we find it hard to avoid the conclusion that there will be a steady decline in the need for traditional professional workers.

During the year after the book’s hardback publication in October 2015, we tested this line of argument on audiences of professionals in more than 20 countries, speaking to around 15,000 people at over 100 events. The response, frankly, was mixed. Our work seems to polarise people into those who agree zealously with our thesis, and those who reject it unreservedly. Both sides argue their views passionately.

This divide corresponds largely with current views on AI: some argue that we are entering an entirely new epoch, while others dismiss this as hype, maintaining that we have been through similar transitions before. We have found that accountants are usually receptive, lawyers are largely conservative and journalists seem to be resigned. Teachers are either sceptical or evangelical, doctors tend to dismiss the idea of non-doctors having a view on their future, architects express considerable interest in new ways of working, management consultants see more scope for change in other professions than in their own, and the clergy have been more or less silent.

In light of feedback and our more recent research, do we still really think that one day we will no longer need our trusted advisers? Is it not obvious, we are often asked to admit, that human beings will always want a face-to-face, that we will surely crave the reassurance that a warm, empathetic person can afford a fellow human being?

We have never denied the significance of the great comfort that one person can give another. Indeed, we go further - in our book, we explicitly identify the “empathiser” as an important role in the future. Nonetheless, our experience - as researchers and advisers to the professions - suggests that many recipients of professional service are actually looking for a reliable solution or outcome, rather than a trusted adviser per se.

Fast-forward a few years, to a time when the level of output of, for example, an online medical or legal service is very high and its branding is beyond reproach. This of itself will offer its own level of comfort and reassurance. In many circumstances, this will be enough for patients and clients, and will be consistently more affordable than the empathetic adviser. Understandably, many professionals remain deeply sceptical, and want to insist that there will always be tasks for which humans are better suited than machines.

But there is a danger of being excessively human-centric. In contemplating the potential of future machines to outperform professionals, what really matters is not how the systems operate but whether, in terms of the outcome, the end product is superior. In other words, whether or not machines will replace human professionals is not down to the capacity of systems to perform tasks as people do. It is whether systems can out-perform human beings. And in many fields, they already can.

Extract

Scepticism about the role of machines is perhaps most compelling when expressed in human terms - when, for example, it is asserted that, “of course, machines will never actually think or have feelings or have a craftsman’s sense of touch, or decide what is the right thing to do”. Framed in this way, this sort of claim appears convincing. It is indeed hard to imagine a machine thinking with the clarity of a judge, empathising in the manner of a psychoanalyst, extracting a molar with the dexterity of a dental surgeon, or taking a view on the ethics of a tax-avoidance scheme.

Robots v experts: are any human professions safe from automation?