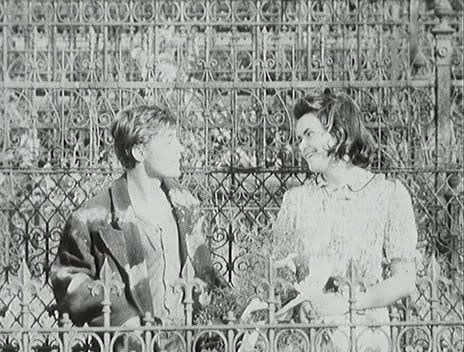

Diamonds of the Night (Jan Nemec, 1964)

Films about the Holocaust always seem to be popular -- probably because they give us enough pain and suffering onscreen to arouse our emotions, and at the same time portray a kind of human dignity that emerges unscathed from the wreckage. Schindler's List and The Pianist come to mind. In stark opposition to these shining examples of the Holocaust film stands Jan Nemec's Diamonds of the Night: a simple film about two Czech Jews who escape from a train taking them to the concentration camps. It's aggressively anti-realist and non-psychological, as well as lacking any linearity. Much like another Czech film dealing with the Occupation, Juraj Herz's The Cremator (1969), it has a very poetic, musical flow, as events and images repeat; memories, actions and fantasies mingle together to the point of being indistinguishable. It's a film without beginning or end, and seems to imply that the German occupation of Czechoslovakia was just as much of a surreal, dreamlike experience for the people who lived through it: a waking nightmare.

Jaroslav Kucera's camerawork, normally known for the fantastic color experiments in films like Daisies (Vera Chytilova, 1966) and Cassandra Cat (Vojtech Jasny, 1963), is here used to quite a different effect. Diamonds of the Night is a film of extremes: extreme darkness in some scenes contrasted with a glaring white light in others, an extreme silence punctuated suddenly by explosive noise. The effect is sublime and terrifying. Despite the subject, this isn't an ugly film; the woodland scenes in particular have an exquisite use of focus, as trees fade in and out of view, and the sun shines through the tops of the branches. It's every bit as graceful as the closing shots of Tarkovsky's Mirror. Other sequences have the haunting stillness of an Atget shopfront, devoid of people, saying nothing but at the same time saying far too much.

And at the other end of the spectrum, Kucera's camera is seized by sudden bursts of energy -- moving with lightning speed down streets, across the woods, through fields of wheat, always dogging the footsteps of the escapees. Toward the film's end, as the boys are being chased by a party of German riflemen, the camera practically falls on them with increasing weight, hurtling at them with all the force of a gunshot.

The editing in Diamonds of the Night is often dialectical, but used to much more poignant effect than the propaganda of Eisenstein's work. It becomes particularly obvious by the film's last scenes, in which the triumphant Nazis celebrate the capture of their victims. The old men stuff their faces with food and beer, and dance around the room arm in arm, while shots of the boys drinking water from a stream are intercut with the present action. The contrast between abundance and poverty doesn't really smack of a moral judgement, but only serves to make a distinction. Even the men themselves don't appear to know what they're celebrating: the capture of two unarmed boys by twenty armed men doesn't warrant a feast. It all makes for a very pathetic display.

Nemec also avoids any trace of maudlin sentimentality, and there is no sense of a bond made between the two boys. We see them trading food for footwear with each other, not out of friendliness but out of desperation. When one collapses, the other continues to go on without him. Their dialogue is minimal. If anything, Diamonds of the Night is a film about the necessity of survival. We are plunged into a world of ugliness and despair, into a universe that is wordless precisely because it exists outside of language, outside of speech: it is the indescribable, the face of the void. The night of their escape, one boy whispers to the other, "Come closer to me." Far from a banality, it's a cry for help. But the two never seem to bridge the gap that separates them now, for communication fails in light of more urgent needs like a stomach to feed or an infected foot to bandage. What drives them forward is the thought of what will happen if they stop: that is, they will either be caught by the Germans or consumed by ants. Actually, I'd go so far as to say that both fates come to signify the same thing. Stripped of a political context, capture by Germans or by ants amounts to the end of life and nothing more.

Diamonds of the Night begins with the gunshots of a chase and ends with the gunshots of a capture. Like the story by Ambrose Bierce, "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge," one wonders if the space between the two events even took place at all, or if it was merely the fantasy of a man's imagination in the seconds prior to his death. Either way, the protagonists don't come out of the film with any greater understanding of their situation. There is only the memory of happier times now out of reach.