BOOKS: Secrets of the Red Lantern by Pauline Nguyen

"... my parents were never relaxed about showing tenderness and understanding with us as children. Whether it was out of disinterest or necessity, they were workaholics who instead poured their knowledge and affection into the food they cooked to feed their children. A strange way to show parental love, but I have grown to accept that this was perhaps the only way they knew how. A dish of bitter melon soup is a dish of reconciliation. When we quarrel, we cannot speak the words 'I am sorry' - we give this bittersweet soup instead. In another instance, the sharing of a particular meal can offer the sentiment we each crave to hear: 'It's good to see you again - I've missed you'. On rare occasions, too few to forget, I have understood the longed for words, 'Please forgive me'. (Pauline Nguyen, Secrets of the Red Lantern)

Blurb: Secrets of the Red Lantern is a bittersweet family saga in which treasured recipes form the threads that bind members together for life. It is both a moving memoir and a dazzling collection of sumptuous Vietnamese recipes, complete with beautiful food, location and personal photography. Pauline Nguyen tells the honest, difficult story of her family, following the journey of her parents from their homeland in Vietnam on their escape to Thailand as refugees, and then on to their eventual resettlement in Australia. They moved to Sydney's most vibrant and notorious Vietnamese enclave where Pauline and her brother Luke grew up. Pauline, Luke and Pauline's husband Mark Jensen now run Red Lantern, an acclaimed, modern Vietnamese restaurant in Sydney's popular inner-city area of Surry Hills. At the heart of this story is a love of food. It helped to placate homesickness, became central to the family's early success in Australia and was sometimes the only language the family could use to communicate with each other. In the end, it was this shared passion for food that reconciled the family and help create Red Lantern's success.

*

Secrets of the Red Lantern, Stories and Vietnamese recipes from the heart was a book that Papa Koala recommended to me. He's been reading it and appears to have been enjoying it. I was a bit sceptical. I find myself a bit cynical these days about the bombardment of books by Asian people about their Life of Woe and Persecution - stories that seem to only further emphasise that We Are Different O Pity Us. Nonetheless, the book is absolutely gorgeous-looking so I bought a copy for Papa Koala at Christmas and this morning when I was pottering about the mall with Mama Koala, I decided to buy her a copy, too. She was feeling tired today so I sat down and read it first.

I felt my cynicism dropping away almost immediately. 377 pages long, there are dozens and dozens of recipes for different traditional Vietnamese dishes. It's hard for me to say whether this is a recipe book that is interspersed with a family's compelling history or whether it is a history of a family into which recipes are integrated.

Sleek, attractive with beautiful photographs it looks just as sophisticated and comprehensive as a Western cook book so it was odd to see Mama Koala's homely home-cooked food dressed up to look so fancy and exotic. I thought it would be nice for her to be able to thumb through the book and smile in recognition at all the different dishes that she cooks for us.

As I don't cook, I merely enjoyed looking at the pictures, smiling in recognition of homecooked meals that I have eaten since a wee koala and also smiled and wiped away tears at the stories that Pauline tells of her childhood and growing up. She writes in an extremely matter-of-fact manner. Most writers whom I describe as 'Asian writers' tend to adopt a very flowery, over the top style which I think panders to notions of Oriental mysticism and exoticism. Kind of the Asian equivalent of speaking forsoothly. It usually bugs the hell out of me because most Asians I know don't really talk like that and for me a story is best told in plain words and from the heart.

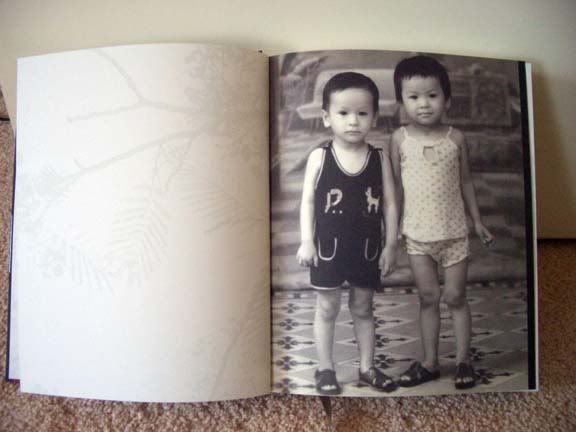

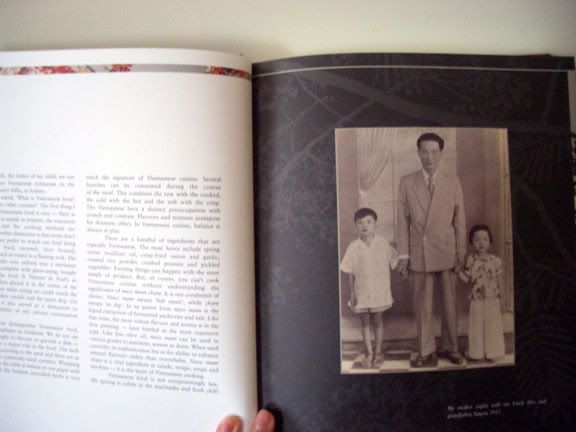

Nguyen tells her story in a very blunt, engaging and frank manner. She shares a lot of family photographs and things which your average Vietnamese/Chinese family would consider to be 'family matters' not to be shared with outsiders. I have no idea how her father feels about this book. On the one hand, she clearly loves and adores him, on the other hand, she paints a picture of a rather typical, despotic, autocratic Asian father who is not very good at expressing emotion, showing love and 'saying sorry'. In her first chapter she writes: "In my family, food is our language. Food enables us to communicate the things we find it hard to say."

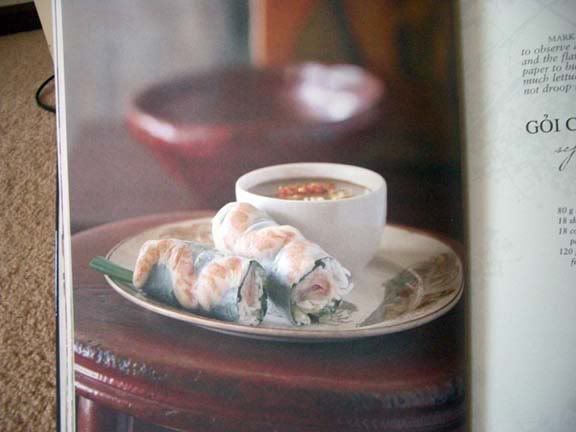

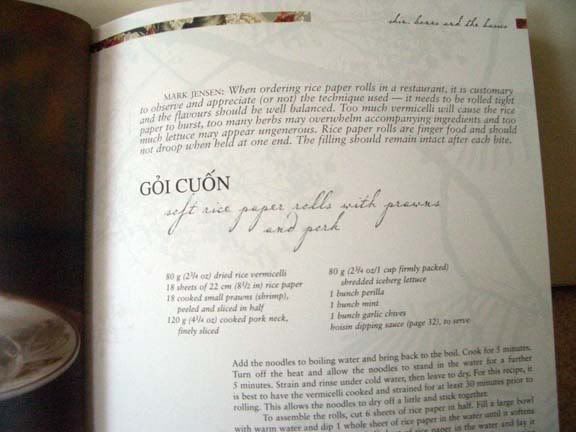

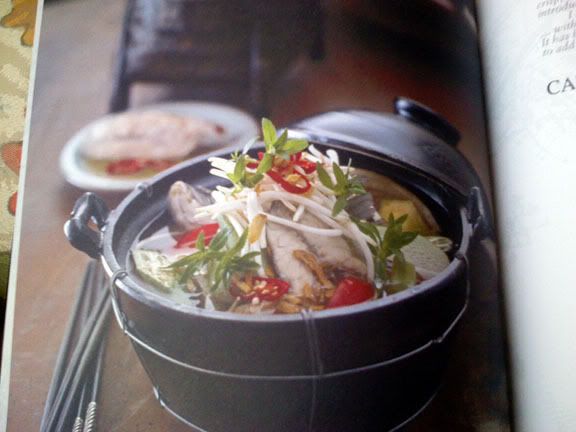

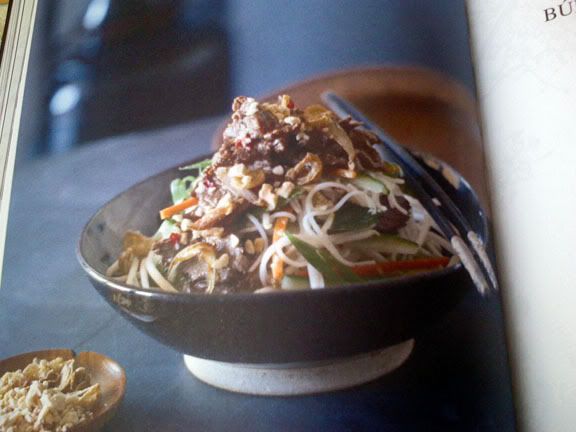

First of all the food. Ummm. Yum? The photographs, recipes, descriptions and explanations make your mouth water! :)

I love Nguyen's 'summary' of Vietnamese food in the first chapter:

Many have asked, 'What is Vietnamese food? How is it different to other cuisines?' The first thing I always say is that Vietnamese food is easy - there is no mystery to it. It is simple to prepare, the execution is mostly quick and the cooking methods are straightforward. Another distinction is that ovens don't exist in Vietnam; we prefer to watch our food being cooked - deep fried, steamed, slow braised, chargrilled, barbecued or tossed in a flaming wok. The only oven my family ever utilized was a miniature rotating 'Tiffany' complete with glass-casing, bought second-hand at the local St Vincent de Paul's in Bonnyrigg. We often placed it in the centre of the dinner table so that while eating we could watch the meat brown, the skin crackle and the juices drip. On many occasions, it also served as a distraction to prevent the possibility of any serious conversation arising at dinner.

What distinguishes Vietnamese food however, is its emphasis on freshness. We do not use fresh herbs sparingly to flavour or garnish a dish - instead, they play a major role in the food. The herb selection varies according to the meal and there are many as a different commonly-used varieties. Wrapping savoury dishes at the table in lettuce or rice paper with an abundance of the freshest uncooked herbs is very much the signature of Vietnamese cuisine. Several bunches can be consumed during the course of the meal. This combines the raw with the cooked, the cold with the hot and the soft with the crisp. The Vietnamese have a distinct preoccupation with crunch and contrast. Flavours and textures juxtapose for dramatic effect. In Vietnamese cuisine, balance is always at play.

There are a handful of ingredients that are typically Vietnamese. The must haves include spring onion (scallion) oil, crisp-fried onion and garlic, roasted rice powder, crushed peanuts and pickled vegetables. Exciting things can happen with the most simple of produce. But, of course you can't cook Vietnamese cuisine without understanding the significance of nuoc mam cham. It is our condiment of choice. Nuoc mam means 'fish sauce', while cham means 'to dip'. In its purest form, nuoc mam is the liquid extraction of fermented anchovies and salt. Like fine wine, the most robust flavour and aroma is in the first pressing - later bottled as the most expensive type. Like fine olive oil, nuoc mam can be used in various grades to marinate, season or dress. When used correctly, its sophistication lies in the ability to enhance natural flavours rather than overwhelm. Nuoc mam cham is a vital ingredient in salads, wraps, soups and stir-fires - it is the heart of Vietnamese cooking.

Vietnamese food is not overpoweringly hot, the spicing is subtle in the marinades and the fresh chilli is added at the table, allowing each person to increase the heat as desire.

In addition to the recipes, the book documents the escape of the Nguyen family from Vietnam and their eventual resettlement in Australia in Cabramatta, a part of Sydney that has become famous/notorious for crime, violence and drugs. I visited Cabramatta often as a child but reading Nguyen's accounts of growing up there, realise that I never really knew the place. These days, some of the notoriety has faded and it's a fun place to visit for yummy food, vibrant street scenes and a buzzy atmosphere. Nguyen offers a wonderful insight of a child growing up in Cabramatta and her views on the notoriety of one of Sydney's most fascinating suburbs.

Cabramatta has never been an 'Australian' suburb, it is simply an area that housed one wave of immigrants after another. The European contingent comprises Dutch, German, Polish, Serbian, Croatian and Macedonian. The Asian overlay comprises Vietnamese, Laotian, Cambodian, ethnic Chinese from mainland Chinese and South-East Asia, as well as Russian-speaking Chinese. Timorese, Turkish, Lebanese, Latin American and Australians also share the suburb. The churches and temples, all within close proximity, cater for a wide range of denominations and faiths including Russian Orthodox, Catholic, Baptist, Anglican and Buddhist.

....

A significant feature of Cabramatta's dynamic commercial centre is that the Asian business people have not confined themselves to the traditional trade outlets. The newsagent, the tobacconist, the electrical goods store, the internet cafe or the lingerie shop is likely to have an Asian entrepreneur. In the late eighties, Asians were buying up large parts of Cabramatta's decaying shopping centres owned by the previous wave of migrants, and turning it into a profitable, vibrant and exotic shopping destination. The most important factor of these transformations was that it provided an employment lifeline for those who would otherwise find it impossible to get a job. It is through diligence and hard work that the proudly self-sufficient refugees of Cabramatta have turned adversity into success in such a short time.

....

The reason why the Asian impact is so complete in Cabramatta was due to the housing of refugees in the nearby Villawood and Cabramatta migrant hotels at the time. Much like the Italian and Greek migrant groups before us, the Indo-Chinese refugees arrived poor, unskilled and with little English. Cabramatta offered employment, cheap housing and more importantly, the comfort of fellow refugees who offered some semblance of the old ways, helping to make their lives more bearable in a foreign country.

People have criticised the Vietnamese for sticking together, but there are pockets of nationalities in every country. I have visited Chinatown in New York, Paris, Barcelona, Rome, London, Sydney and Melbourne. I have seen Little Italys everywhere in my travels. I have even stayed in patriotic Australian villages in Vietnam, Paris and London. All over the world, various races and cultures group together. Having been through what the refugees have been through, it is only human nature to seek solace, companionship and mutual support among our own people. Indeed, there are Vietnamese in Cabramatta and, yes, we have made an impact on the community. We have had our fair share of problems but this has been the case with every new wave of immigrants to every country in the world.

One of the biggest myths about Cabramatta is the belief that the suburb is a ghetto full of Vietnamese who are unable or unwilling to adapt to Australian society. This coincides with the even more popular myth that Cabramatta is a drug-saturated hot spot, full of junkies, corruption and Asian criminals. The rise of gangs and drugs during the mid-nineties had deeply wounded the community, but it was the media who inflicted the most harm. Even today, if there is a crime in Cabramatta, it receives a huge amount of publicity - a crime in another suburb hardly warrants the same exaggeration.

The media frenzy reached its peak following the violent murder of local Member of Parliament John Newman in 1994. A gunman had shot him dead in his driveway. The headlines described it as Australia's first political assassination. Deeply saddened by the news, I realised too well the repercussions of his death and the field day the journalists would have.

John Newman had been a crusader for the Vietnamese people and a strident campaigner against Asian crime and Asian gangs. A dominant force for tourism in Cabramatta, he had a vision for the suburb as being a thriving multicultural metropolis ... As expected, the bad publicity escalated after his murder, bruising the community on both a social and economic level. Business revenue dropped terribly and the area lost over $10 million in tourism. Worst of all, the bad reputation incited fear and misunderstanding, tarnishing our prospects at school, in the workforce and in society.

When the media linked the assassination with events that happen in Cabramatta every day of the week, they neglected to mention the decent people - the honest, law abiding, hard working people who had chosen to work, raise their families and make a life for themselves in this multicultural suburb. Negative press continued and, for a time, even the residents became too scared to walk in the neighbourhood streets after dark. Media beat-ups and xenophobia are nothing new to the Vietnamese people. The real story was that we were down but not out. How could they dampen the spirit of people who have been through so much to get to where they are? How could they expect to keep down a community of survivors dominated by a race who have a history of surviving?

Over time, the wounds healed and the bruises faded as the entire community banded together, determined to fix the issues affecting it.

....

In the rare downtimes, the suburb is calm, quiet and peaceful. Otherwise it swarms with activity as people weave in and out of the maze of alleyways in search of great bargains, competitive prices and Asian delights. These days, there are other pressing local government issues, such as increased parking to deal with the congestion caused by daytrippers who flock to the suburbs on the weekends. As with our family, most Vietnamese who work in Cabramatta actually live elsewhere. Many have come from the South Vietnamese middle class and, as they have acquired more wealth, they have risen above their low socio-economic place in Australian society and swiftly moved to more affluent areas.

....

It took a number of years for the Vietnamese people of Cabramatta to repaint the maligned canvas that had portrayed them. These days, Cabramatta is back on track to being recognized as the ultimate destination for lovers of Asian cuisine. It is just as well for my food-obsessed parents that market day in Cabramatta is every day of the week. Fruit, herbs and vegetables arrive crisp, firm and fresh every day, direct from the market gardens nearby. Most stalls carry the full range of Australian and Asian produce. Seafood and meat is fresh and reasonably priced. The butchers offer familiar cuts, as well as the Asian preference of meat closer to the bone. The offerings at the fish markets are extensive, with almost every type of fish imaginable on display.

In reading the book, I found myself nodding and smiling at Nguyen's description of the food forced upon her by her mother - how weird and exotic her lunches always seemed compared to those of her classmates. I went through the same experience and the food for which I was mocked as a child (and which I used to secretly throw in the rubbish and long for devon and tomato sauce sandwiches!) is now trendy and popular :P These days you couldn't pay me to eat a devon and tomato sauce sandwich and I'd eat a Vietnamese prawn handroll any day of the week :)

Nguyen's recollection of childhood and her teen years reminds me of my own. A lot of bitter, sweet and sorrow all mixed in together so that sometimes it's impossible to separate the different threads. All the memories are laced by a combination of all three. Her descriptions of her strict and austere father are fascinating and the eventual reconciliation is very moving. I didn't cry, but I definitely did tear up.

It's a wonderful, wonderful book. If it wasn't so heavy I'd take a copy of it back to Beijing with me. :) You can buy it here. Also, page 190 to 191 has a wonderful 'essay' about phở, its symbolism and what it means to the Vietnamese. Nguyen admits that it's not her favourite food but recognises its importance and significance. She also says that for a dish 'steeped in such history and tradition, it is unprejudiced and wholly accepting of individual evolution and personal interpretation'. I love the bit where she says: " Phở has integrated so completely into Australian society that there is no longer the need to refer to it as 'beef noodle soup' - everyone knows what phở is".

:)