"Another Yesterday: A Speculative History”

Going through my old fics I found the very first one I ever wrote.

It was 1999 and I'd seen a few Beatles stories and so I thought

I'd try to do one.

This was actually really popular in the Beatles fandom at the time

and was reposted many times. But I never wrote another one. And I never

wrote any more fics until... well, you all know.

So here it is.

"Another Yesterday: A Speculative History”

By Gaedhal

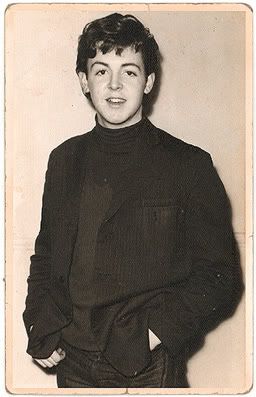

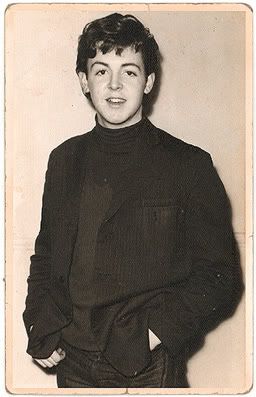

Q. “If you hadn't been a musician, what do you think you would have been?” (Tony Carter, Manchester)

A. “The only thing I could have probably qualified for was teaching. So I might have been an English teacher.” (Sir J.P. McCartney)

Another Britain, 1992:

Even after all these years, Paul felt a certain liberation at the end of term. There was laughter in the halls, and running, which would ordinarily not be tolerated. But the joy welling up from the boys as they burst out through the big doors and across the playing field was so infectious that Paul could hear a bright ghost of a tune inside his head, lively and leaping. This was always happening, no matter how he might try to suppress it. When he was reading aloud from “Fern Hill” in front of the class, or correcting essays, or driving through the old city, these little tunes would just come to him - and then be gone.

“Sir?” A quite small boy was standing at his knee.

“Yes - em?” He couldn’t place the chap - too young to be in any of his classes.

“Keenan, Sir. Joseph. My brother is Henry.”

“Yes, of course. Keenan Minor. What can I do for you?” Paul always pumped up a bit in front of the smaller lads, taking the mickey out of their deep solemnity, playing the part of The Master with special élan.

“Well, Sir, some of the boys say that you mightn’t be back next term. That you’re going to a new school to be the Head. Is that true, Sir? Because it isn’t fair that I haven’t had a chance to be in your class, Sir. I’d like you to remain until I get the opportunity.” He paused. “And Old Bingham will take over your class and he’s a horrible old snout, Sir, if you don’t mind.”

Paul could hardly keep himself from laughing aloud, but the small face was deadly serious and deserved a serious reply.

“An old snout, is it? Well, Master Keenan Minor, we will do what we can, won’t we? But I can’t make any promises. Remember, we can’t always have it our own way. We must keep our expectations in moderation. And when we cannot, the British way is to dig in and carry on. Now, be off Keenan, and perhaps I’ll see you next term.”

As he watched the boy shoulder his schoolbag through the heavy door, Paul felt badly that the lad was doomed to a future of Snouty Bingham. He knew they had a name for him, too. Macca. Cheeky of them, for it referenced his carefully smoothed over, but still detectable Liverpool origins. But it was fond, as well. They could have called him worse. Paul also felt a right prig to have mouthed such platitudes to the child - clichés that his own masters had undoubtedly repeated to him in his time. He long ago promised himself that he would never be that kind of teacher. But it was hard not to fall into the trap of the easy answer. Besides, the boy was right: he was leaving, taking over a school posher even than this one - and one deeper out into Cheshire, so far from the crumbling halls of his childhood and youth.

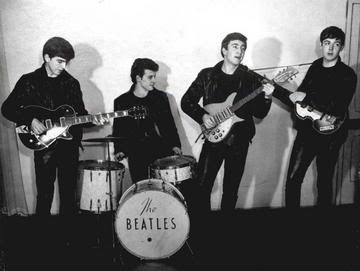

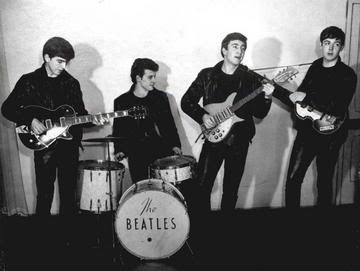

He pushed open the door and looked out across the empty playing field. He thought for a moment that he saw four shaggy lads in black leaping and jumping in exhilaration. And that little tune went through his head once more.

******************************************************************

The sign over the hairdressing shop, Gear Hair, was shabbier than Paul remembered. And Mathew Street was dirtier, more neglected. It angered him that his brother stuck it out here instead of moving to one of the new shopping plazas in the suburbs. It depressed him to see this place, which once had such spirit, looking like a war zone, and this particular street, which had been so full of life, nothing more than a dead end.

Mo was sitting behind the reception desk, counting the day’s take. Her husband, Ritchie, was combing out a vast woman with tortuously bleached hair. In her pink plastic smock she looked like a large mound of cake with strawberry icing. His brother was not to be seen.

“Oh my God, Mo! Hide the cash! It’s a raid from the grammar police!”

“Ta, Ritch. Maureen.” He suddenly felt uncomfortable. He looked for a place to sit, but didn’t want to slip into one of the whirling pink barber chairs; the plastic covers on them looked grimy.

“Mo, he’s come to get me, ya know. I never turned in that book report on thingamy... That book, ya know.”

“There’s lots of books, Ritchie.”

“Ah, well, I never finished one, anyway. I knew my wicked past would come back to haunt me!” Ritchie turned the fat lady around to face the mirror with a practiced spin. He patted her hair. “You’ll be watching your grammar now, then, Mrs. Suggins, because Our Paul is a schoolmaster and he carries a cane to thrash those of us what don’t speak proper. Ain’t that a fact, Mo?”

“Sod off, Richard.”

“I love you, too, Luv.”

“Actually, I was looking for my brother.”

“Well, you won’t have far to look - he’s down the Grapes where he is every day after closing.” Ritchie whipped the plastic sheet off Mrs. Suggins and shook it out on the floor. “He’s likely with Roger and them other Bolshie lads. Them poets. They have readings and sings of a Friday.”

“That lot,” came Mo’s voice from behind the desk. “An old lot of alkies they are. Always dreaming. Always moaning about what might have been. You’re the only one who's made anything of yourself, Paul, by getting out of this lot ’stead of being trapped in this godforsaken hellhole.”

“Ah, Miss Cheer o’ the ’Pool speaks!” Ritchie clucked as he trapped Mrs. Suggins’ discarded curls in between the broom and the dustpan.

Mo took another long drag on her cigarette and Paul could see the lines etched gravely around her eyes. Maureen had been quite beautiful in her day, one of the prettiest and sweetest girls on the scene. He’d thought Ritchie lucky to catch her at the time. He suddenly felt ancient. Fifty. It hardly seemed possible. He felt younger around his students; they were so vital that it was easy to pretend that the years were not passing. But he’d kept himself well. He’d packed in the ciggies long ago, he and his family were all vegetarians. He belonged to a club and played tennis there twice a week. Ski holidays. Spain or Corsica or Turkey for the sun. Maybe he was a tad soft, but it suited his droopy baby features better than the predatory sharpness his brother affected.

He looked at Ritchie, a stunted figure, his hair and neat little beard very grey, the hound-dog face melancholy even as he bustled around the shop, whistling and sweeping up the ends of hair and curling papers. Maureen’s waspish comments seemed to pass over him like air. This shop was his dream and nothing could spoil that for him. He and Michael owned it free and clear and he was happy fussing over the ladies and making nice cups of tea all day. He was happy. It was better than being a labourer, which would have been his fate. He’s missed so much school as a child - one horrific illness after another - that he was practically illiterate.

Hairdressing was a step up for Ritchie. But Paul couldn’t help feeling that for his own brother it was a step downward.

******************************************************************

The Grapes was even more bedraggled than he had remembered. He and the lads he ran with had spent many hours there thirty years before when he had been in a beat group that played in a cellar club a few doors down. The group and the club and the whole scene were long since gone, but this old Victorian pub remained. The interior was dark and heavy with the smell of smoke and rising damp. Through the haze he could see Michael and Roger and their mates sitting in the same corner he and his had sat in the old days. Mike had a pint in his hand and was talking - as usual - in an animated manner. Roger, a little more stooped and bald than he’d last seen him, was nodding and pushing his glasses back up on his nose. Paul started; the gesture reminded him of someone else, a long time before.

Mike was in mid-sentence when he saw his brother. He paused and stared and they all turned around. In a moment Paul was enveloped in greetings and hands slamming him on the back. He was pushed into a chair, a pint put into his hand. They seemed to be shouting at once, congratulating, chiding, insulting, wrapping him in Scouse good will and excitement. They were all so glad to see him he was embarrassed. It was as if he had just returned from a long exile in the States or Australia. In fact, he lived less than an hour away in a well-appointed detached house in a professional neighborhood in Chester. All the others lived a short bus-ride away: Michael, since his divorce, in a flat so small it was practically a bed-sit, the others in council-houses and semi-detacheds on the same streets where they’d grown up. Mike, of course, was Ritchie’s partner in the salon. Roger was a teacher, like himself, but in a school deep within the old city, a school filled with plenty of grubby, red Irish faces like their own had been, but also the black and brown faces of new immigrants’ children. Paul admired Roger - he had always been a man with convictions. He could teach in a better school, far from the decaying center, but he stayed because he believed he could make a difference there. And he was a published poet, a creator. Paul felt a pang - he wished that he had a talent like that. He’d tried painting when he was younger, but a good friend of his had been so much better that he gave it up. And he taught the great writers every day and knew that he could never match their words, so what was the point? Once upon a time he had even fancied himself a musician, but after some youthful playing in a beat combo, he’d given it over; after all, he had no musical training and the little tunes he often made up to amuse himself and his children didn’t amount to much. The kids had all had lessons, and he could doodle out a few pub songs and old Elvis numbers on the spinet, but... He put it out of his mind.

Roger and Mike were talking about their weekly poetry readings.

“Aye, Paulie, you ought to come out Friday - me and Rog do these comedy bits - along with the poems, of course,” Michael bowed slightly to Roger, who stared impassively through this wire-rimmed specs. Paul suddenly felt an odd jolt to his stomach, as if a goose had walked over his grave. Roger’s long, ironic face, the glasses, the half-smile - Paul saw Johnnie sitting there, in that same pub, in that same worn-down chair, smiling condescendingly at something someone else had said, looking sidewise at Paul, sharing his contempt with him like a drag on his ciggie. Paul felt ill. John was dead over twenty years now, but he could sense his presence elbowing through the room, filling this filthy, ruined city. He should have never come back, even for a night…

“I have to go,” Paul stood so suddenly his head was light.

“Here, now, wack,” Mike pulled him back down. “You look right spooked.”

“Brother, you are positively psychic.” He picked up his pint and tried to steady it against his lips.

“Don’t go now, Paulie - Willy’s supposed to turn up, and Adrian. You haven’t seen that lot in an age. We’ll have a right good bit of crac, just like the old days.”

Another man appeared and dragged up a seat. He was younger, but no longer young enough, dark-haired, with a pale, pointy face going fat around the edges. His piercing eyes glowered through thick, black-rimmed glasses that had been clumsily repaired at the edges. He carried a bulky, battered manuscript to his chest like a child, an assortment of pens jiggling against it in his breast pocket. He whispered urgently to Roger, who waved and nodded absently.

“Dec - meet Mike’s brother, Paul. Paul, Dec is a teacher, too, like you.”

Paul held out his hand, but the newcomer didn’t take it. Instead, he peered at Paul through those glasses, wary and hostile.

“Yeah. I’ve heard tell of you: the family success story. How’s the bourgeoisie treatin’ you?” Dec’s voice was soft, but the edge was menacing. Something about the fellow seemed ready to explode. He looked like the kind of office non-entity who turns up as a mass murderer one day on the front page of The Sun.

“Ah, I wouldn’t say that exactly - I get along, same as all of us, Mr...?”

“MacManus. Declan.”

“Well, Dec, I teach just English Lit out in Cheshire - I’m hardly a candidate for the next New Year’s List.”

Roger intervened. “Dec teaches computers at one of the technical schools. Wave of the future, computers. And I can barely get my old typewriter to work.”

“Computers, eh? I have a Mac at home. Handy for doing my notes and letters and things.”

“Well, I teach computer programming to a bunch of illiterates who can’t afford to have Macs sitting on their antique desks in their posh digs. Occasionally one of ’em even gets a job in an office that almost pays what they need to live on. Does my heart good when that happens.” Dec fumbled with a cigarette, offering the pack around the table, but pointedly not offering one to Paul. The hair on the back of Paul’s neck raised, like a challenged dog ready for a fight. He almost enjoyed the feeling.

Michael, leaned in between them, taking a ciggie from the pack. “Dec is a writer. A fine one. He reads with our lot every week.”

“Oh, and what do you write, Mr. MacManus?” Paul suddenly desired one of those cigarettes more than anything. Funny, he had packed that in years ago, but he wanted one just the same.

“Nothing that sells,” he intoned, ominously.

“Now, then, Dec - did that friggin’ thing come back home again?” Michael poked at the dirty manuscript. The man flinched, as if Michael had touched a broken bone.

“Aye. Today. The fourth time.”

“Wankers. Sod ’em.” Dec’s perambulating manuscript was obviously an old joke among the lads.

“It’s the friggin’ Capitalist Establishment. They hate hearin’ the Truth!” Dec’s voice rose about the dim. A few men at the bar and in the corner clapped their hands. Someone shouted: “Bring on the Revolution!” while another countered, “Bring on another round!” The bartender shot Dec a warning look and he sunk in his seat.

Michael leaned over to Paul. “He’s just trying to take the piss out of you, that’s all. That’s Dec. He’s really brilliant, ya know. A mad piss-artist.”

Paul stood up. “I think I had best be going - it’s a long drive... A long way to get home.”

Michael and Roger stood up. Paul put on his coat and nodded to the table. “I’m glad to have met you, Dec. I hope you have some success with your work. If Roger thinks you’re a good writer, then you are.”

“Yeah, why don’t you...” He stopped and looked up at Roger.

“Dec, I was hoping that Paul would come Friday to the reading. Why don’t you come and read those poems you showed me last week, Dec? The ones about being a child in Liverpool in the Sixties? I’m sure Paul would appreciate hearing them. He’s a Scouse, too, at heart - aren’t you, old man?” Roger looked at Paul, but took Dec’s arm and directed him towards another table.

“I might do,” he murmured, engrossed in his pile of ragged papers and his misery. He sat down in the corner, alone. Michael shook his head, but Roger watched him ruefully.

“Another talent destroyed by this fucking society,” he said, flatly. “There was a time I thought something was going to happen here - right here. In Liverpool - in England. You could feel it in the air: the music, the poetry, the energy... and then - I don’t know. Nothing. Destroyed entirely. Like our mate, there.”

Paul turned to the door, his scarf around his neck. “I was thinking the same - but of someone else,” Paul said.

Roger looked at him. “John,” he said. It wasn’t a question.

******************************************************************

Pulling up to the old former church hall in Woolton, Paul had a strong feeling of deja vu. Certainly, he had been there before, although he couldn’t remember the circumstance. Perhaps he’d played there with the beat group when he was a lad. Yes, he was sure of it. He could remember humping the equipment up those steps and through the hall door. Carrying in his amp, pieces of Tommy’s drum kit. Or had it been Pete? No, that was somewhere in Everton, another old church that looked like all the other old churches.

He couldn’t remember things anymore, not the way he used to. It seemed so long ago. Thirty years? More? He tried to recall whether Stu had still been with them then. But all he could see was John, in his black leathers, ciggie dangling from his mouth, ‘supervising’ the operation. And George, trotting back and forth, ever eager to please. Christ, he thought, George! How many years had it been since he’d thought of him? It must be twenty-five years since he’d left the ’Pool and gone to the States where his sister lived with her husband. Well out of it, he’d thought at the time. Paul wondered idly if he should have done the same. But he couldn’t complain - it had been different for him. Paul had had his father to push him on, and he’d gone back and gotten an education. George had a good mind, but not for school. There had been nothing here for him. He’d have ended up - like John? That was a chilling thought.

And what about himself? How had he ended up? Really? Funny, but he had never worried about himself. He had always assumed that he would do well. He knew he had the looks, the charm, and a brain on him. His old dad, and his mum before that, had instilled purpose in him, told him he could do anything, was made for something better than the common lot. And he had believed it. He charmed the teachers at school, just like he’d charmed the girls, and done well with both. He’d gone on to university and taken a degree. He’d married a Southern girl, a Sussex girl from a well-to-do family (her father was a solicitor), who was also a teacher. A charmed life, some called it. He fit in at all the affairs where everyone was from a posh school and had a job that wasn’t dependent on government grants. He could talk a good game about art and the latest plays and books - that was his specialty, as an English master. He could talk music, which used to be his passion but was now just another subject to bring up at a dinner table or drinks party. In his bespoke suits and designer shirts he looked as prosperous and sleek as any Cambridge grad whose father was a baronet. When he was younger - well, he’d been a good-looking bloke and he knew it well. Looks and the right bit of chat could take you a long way. No, he hadn’t gone to the bad like - like others had.

So why did he feel this guilt? As if anything could have saved John - as if the band they fooled around with, or school, or even his girl (Paul winced as Cyn’s worried, overly made-up face crossed through his mind) could have pulled him out of the gutter that was of his own making. Paul thought of the last time he had seen Cynthia, standing at the gravesite. He knew she was pregnant, too, that made it so much worse. Her bleached blonde hair had whipped around her face, the tears streaking her mascara down like wild animal tracks. Aunt Mimi had turned away from her - turned away from them all - blaming them. Blaming them. Paul could hear John’s voice in his head - had it been in that very pub, or one just like it somewhere in the city? - “I’m either going to leave this city fucking famous - or dead.” He’d meant it.

Cynthia had gone away somewhere; they later heard she’d married, but he never heard if she had the child or what happened to it. Paul couldn’t imagine her not having it - not Cyn - so somewhere out in the world John’s kid was going about his business, maybe unaware, or uncaring, about the crazy man, the fucking genius who had been his father - and Paul’s best friend.

Paul found it hard to get close to people after that. He had other friends, but not close ones. Ivan moved to the South and got into university, taking a degree in Classics; they soon lost touch. George finished his apprenticeship and moved on to America. Paul even felt distanced from his brother: Michael was so connected to the old city and Paul could barely stand to be there: every street, every barbershop, every roundabout was a cold memory. He was physically ill as he paused at certain crossings, felt a jolt as he saw certain buildings, the backs of young men, heard laughter - it was like being haunted. He flashed on the two of them, heads together in his dad’s old house, cradling their guitars or pounding on the piano after they’d skivved off school....

The hall was set up for the reading, but the turn-out was sparse, to say the least. The broken stage, some battered tables and chairs pulled up close, a tipsy-looking piano at the side, a bar area where a red-faced Irishman was pouring pints out of bottles - that was it.

“Yeah,” said Michael. “I think he’s the Rector! Old sod!”

“Not much of a crowd.”

“Oh, it gets real rowdy later. Actually, they have a fella who plays some music and the kids will show up and dance. Not much life in this old parish anymore, I’m afraid.”

“Not many poetry fans, either.”

Michael shrugged. “It’s early yet.” He guided Paul to the table Roger and Dec had claimed. It was prime territory: near the stage and the make-shift bar.

“Read me this one, Dec. You don’t need to go up on the stage.” Roger was shuffling through the scruffy sheaf of manuscript. The other poet bolted down his drink, stood, and took a deep breath:

“I feel such sorrow, I feel such pain,

I know I won’t arrive on time,

Before whatever out there is gone

What can I do? That day is done.

It’s just a promise that I made

I said I’d walk in her parade -

Hot scalding tears I thought would flow -

Still in my heart they’ll never know.

That day is done,

You know where I’ve gone.

I won’t be coming back:

That day is done.”*

“For Christ sake, Dec! You and the four line rhymed stanzas! You should be writing songs for Top of the Pops!” Michael was laughing as he reached for a ciggie.

“Take that back, you bastard!” Dec reached across the table for Michael’s neck.

“Here! The lot of youse will go out into the street in a minute!” The big Dubliner who had been minding the bar was between them immediately. “This ain’t the first time you fellas have tried to start it up here and I won’t have it! Jaysus! You poets are worse than the bloody bikers!”

Roger hustled Michael across the room, leaving the red-faced Dec to gather up his dirty pages. “Bleedin’ hairdresser... What does he know about poetry or anything? Huh?” Dec glared at Paul. “I suppose because you’re teachin’ at some poncey school that gives your brother the right to critique my work? Why do you come slummin’ around here, huh? I know your story, son. You left your mate high and dry way back when and he went to the bad. Got himself plugged trying to pull off a robbery for a couple of lousy quid. Knocking over a chemist shop with a bleedin’ comb in his pocket. I suppose you think you’re that much better than us all? Go back to Oxford, pretty boy. Or ex-pretty boy, I should say.”

In his confusion, Dec dropped one of his pens on the floor and Paul bent to pick it up. He reached out to return it and then stopped.

“It was a harmonica.”

“What? What did you say?”

“I said, it wasn’t a comb. It was his harmonica. It was in the pocket of his leather jacket. John didn’t know that the owner, a Pakistani, had been beaten up the week before. The man had an unlicensed pistol - old Army issue. John was angry - he’d just lost a lettering job at a sign company, his girlfriend was pregnant, he was trying to get a band together to go over to Germany and play some gigs. His aunt was refusing to give him any more money. He’d gotten 10 quid from me two days before to pay the rent and buy some food - it was all I had to spare from working and trying to go to university at the same time. I couldn’t give him any more....” Paul played with the pen, turning it over and over in his hand. “He wanted me to quit school and go back over to Hamburg with him. I said no - I had a chance for something else. I owed it to my father, to make something of myself. John said... He....” Paul stopped and stared, as if trying to pull a vision out of the air. “I don’t think the man was trying to kill him. He just fired out of fear. And John was doing it out of fear, too. He was like that - completely spontaneous. Spontaneous fear, spontaneous anger at the world. I don’t think he knew what hit him. I hope he didn’t...”

Dec sunk back down in the chair and they both sat silently for a while.

“I’m sorry. I just fly off sometimes. It’s frustratin’ - a frustratin’ life. I keep having flashes of what I could be - Sometimes I see myself in another life - doing something else. Sometimes I’m playing music, or reciting my poems, or - I don’t know. Sometimes it’s so clear: what might have been? D’ya know? It’s all a pipedream. Daft, dreams, right?”

“No, not daft at all. I have them all the time. Sometimes so strong they’re brighter than reality. I hear music and it’s as if I could reach out and touch it...”

“How do you touch music?”

“I don’t know. I’m soft, right?”

For the first time, Dec smiled. “Yeah, I’m one of those crazy men, too. Aren’t we all? That’s why we’re here, living in dreams.”

“You know, Michael was right about your poems - No, wait, I meant that in a good way. Songs lyrics can be a kind of poetry. I - we - John and I used to write songs in the old days. Bad songs, but we thought they were great. You might try putting them to music. You might make a great song out of the bunch.”

“I don’t know anything about music. And who would sing them? I’m no folk singer and these certainly aren’t material for Top of the Pops.”

“You could sing them yourself. Ever listen to Bob Dylan or one of those old boys? Hold it...” Paul got up and moved over to an old upright piano against the back wall. “Try this: ‘That day is done - that day is done.’” He played a couple of chords and noodled around the words of the poem. “Can you play a guitar?”

“I’ve fooled around a bit. My mates used to laugh at me for it. They called me ‘Elvis’ - the prats.”

“Well, “Elvis’ - my mates used to call ME ‘Elvis’! It’s a compliment of the highest order. Maybe we can work something out. It’s fun, really. A rush.” Paul began to play a few more notes, a bit of a melody that came to him sometimes.

“That’s pretty good. You can really play that thing!”

“I used to be good on the guitar, too - they kept trying to lumber me with the bass, but I loved messing with the guitar.” He played another figure on the old piano. “Man, this needs a good tuning.”

Michael was suddenly standing next to him. “Hey! It’s Burt Bacharach or Henry Mancini or one of that lot! You getting into the music again, Paulie? He’s great, really. And I’m not saying that just because he’s me older brother and might cripple me!”

Paul played a bit more. Roger came over and nodded. “I like your tunes, old son. Are you and Dec going to hook up and make us some hits, then?”

“We might!” Said Dec. They turned and looked at him with surprise. “We might, just.”

“What’s that you’re playing, then, Paulie?”

Paul smiled. “Just something I’ve fooled around with. I call it ‘Scrambled Eggs.’”

“Always the joker.”

“You’ll see. You’ll see. It’s never too late to live your dream. Don’t leave until yesterday what you can do tomorrow. Right, Dec?”

“That makes no sense at all.”

“It will, son. It will.”

####

(* ©McCartney/MacManus 1989)

©Gael McGear Sweeney 1999

It was 1999 and I'd seen a few Beatles stories and so I thought

I'd try to do one.

This was actually really popular in the Beatles fandom at the time

and was reposted many times. But I never wrote another one. And I never

wrote any more fics until... well, you all know.

So here it is.

"Another Yesterday: A Speculative History”

By Gaedhal

Q. “If you hadn't been a musician, what do you think you would have been?” (Tony Carter, Manchester)

A. “The only thing I could have probably qualified for was teaching. So I might have been an English teacher.” (Sir J.P. McCartney)

Another Britain, 1992:

Even after all these years, Paul felt a certain liberation at the end of term. There was laughter in the halls, and running, which would ordinarily not be tolerated. But the joy welling up from the boys as they burst out through the big doors and across the playing field was so infectious that Paul could hear a bright ghost of a tune inside his head, lively and leaping. This was always happening, no matter how he might try to suppress it. When he was reading aloud from “Fern Hill” in front of the class, or correcting essays, or driving through the old city, these little tunes would just come to him - and then be gone.

“Sir?” A quite small boy was standing at his knee.

“Yes - em?” He couldn’t place the chap - too young to be in any of his classes.

“Keenan, Sir. Joseph. My brother is Henry.”

“Yes, of course. Keenan Minor. What can I do for you?” Paul always pumped up a bit in front of the smaller lads, taking the mickey out of their deep solemnity, playing the part of The Master with special élan.

“Well, Sir, some of the boys say that you mightn’t be back next term. That you’re going to a new school to be the Head. Is that true, Sir? Because it isn’t fair that I haven’t had a chance to be in your class, Sir. I’d like you to remain until I get the opportunity.” He paused. “And Old Bingham will take over your class and he’s a horrible old snout, Sir, if you don’t mind.”

Paul could hardly keep himself from laughing aloud, but the small face was deadly serious and deserved a serious reply.

“An old snout, is it? Well, Master Keenan Minor, we will do what we can, won’t we? But I can’t make any promises. Remember, we can’t always have it our own way. We must keep our expectations in moderation. And when we cannot, the British way is to dig in and carry on. Now, be off Keenan, and perhaps I’ll see you next term.”

As he watched the boy shoulder his schoolbag through the heavy door, Paul felt badly that the lad was doomed to a future of Snouty Bingham. He knew they had a name for him, too. Macca. Cheeky of them, for it referenced his carefully smoothed over, but still detectable Liverpool origins. But it was fond, as well. They could have called him worse. Paul also felt a right prig to have mouthed such platitudes to the child - clichés that his own masters had undoubtedly repeated to him in his time. He long ago promised himself that he would never be that kind of teacher. But it was hard not to fall into the trap of the easy answer. Besides, the boy was right: he was leaving, taking over a school posher even than this one - and one deeper out into Cheshire, so far from the crumbling halls of his childhood and youth.

He pushed open the door and looked out across the empty playing field. He thought for a moment that he saw four shaggy lads in black leaping and jumping in exhilaration. And that little tune went through his head once more.

******************************************************************

The sign over the hairdressing shop, Gear Hair, was shabbier than Paul remembered. And Mathew Street was dirtier, more neglected. It angered him that his brother stuck it out here instead of moving to one of the new shopping plazas in the suburbs. It depressed him to see this place, which once had such spirit, looking like a war zone, and this particular street, which had been so full of life, nothing more than a dead end.

Mo was sitting behind the reception desk, counting the day’s take. Her husband, Ritchie, was combing out a vast woman with tortuously bleached hair. In her pink plastic smock she looked like a large mound of cake with strawberry icing. His brother was not to be seen.

“Oh my God, Mo! Hide the cash! It’s a raid from the grammar police!”

“Ta, Ritch. Maureen.” He suddenly felt uncomfortable. He looked for a place to sit, but didn’t want to slip into one of the whirling pink barber chairs; the plastic covers on them looked grimy.

“Mo, he’s come to get me, ya know. I never turned in that book report on thingamy... That book, ya know.”

“There’s lots of books, Ritchie.”

“Ah, well, I never finished one, anyway. I knew my wicked past would come back to haunt me!” Ritchie turned the fat lady around to face the mirror with a practiced spin. He patted her hair. “You’ll be watching your grammar now, then, Mrs. Suggins, because Our Paul is a schoolmaster and he carries a cane to thrash those of us what don’t speak proper. Ain’t that a fact, Mo?”

“Sod off, Richard.”

“I love you, too, Luv.”

“Actually, I was looking for my brother.”

“Well, you won’t have far to look - he’s down the Grapes where he is every day after closing.” Ritchie whipped the plastic sheet off Mrs. Suggins and shook it out on the floor. “He’s likely with Roger and them other Bolshie lads. Them poets. They have readings and sings of a Friday.”

“That lot,” came Mo’s voice from behind the desk. “An old lot of alkies they are. Always dreaming. Always moaning about what might have been. You’re the only one who's made anything of yourself, Paul, by getting out of this lot ’stead of being trapped in this godforsaken hellhole.”

“Ah, Miss Cheer o’ the ’Pool speaks!” Ritchie clucked as he trapped Mrs. Suggins’ discarded curls in between the broom and the dustpan.

Mo took another long drag on her cigarette and Paul could see the lines etched gravely around her eyes. Maureen had been quite beautiful in her day, one of the prettiest and sweetest girls on the scene. He’d thought Ritchie lucky to catch her at the time. He suddenly felt ancient. Fifty. It hardly seemed possible. He felt younger around his students; they were so vital that it was easy to pretend that the years were not passing. But he’d kept himself well. He’d packed in the ciggies long ago, he and his family were all vegetarians. He belonged to a club and played tennis there twice a week. Ski holidays. Spain or Corsica or Turkey for the sun. Maybe he was a tad soft, but it suited his droopy baby features better than the predatory sharpness his brother affected.

He looked at Ritchie, a stunted figure, his hair and neat little beard very grey, the hound-dog face melancholy even as he bustled around the shop, whistling and sweeping up the ends of hair and curling papers. Maureen’s waspish comments seemed to pass over him like air. This shop was his dream and nothing could spoil that for him. He and Michael owned it free and clear and he was happy fussing over the ladies and making nice cups of tea all day. He was happy. It was better than being a labourer, which would have been his fate. He’s missed so much school as a child - one horrific illness after another - that he was practically illiterate.

Hairdressing was a step up for Ritchie. But Paul couldn’t help feeling that for his own brother it was a step downward.

******************************************************************

The Grapes was even more bedraggled than he had remembered. He and the lads he ran with had spent many hours there thirty years before when he had been in a beat group that played in a cellar club a few doors down. The group and the club and the whole scene were long since gone, but this old Victorian pub remained. The interior was dark and heavy with the smell of smoke and rising damp. Through the haze he could see Michael and Roger and their mates sitting in the same corner he and his had sat in the old days. Mike had a pint in his hand and was talking - as usual - in an animated manner. Roger, a little more stooped and bald than he’d last seen him, was nodding and pushing his glasses back up on his nose. Paul started; the gesture reminded him of someone else, a long time before.

Mike was in mid-sentence when he saw his brother. He paused and stared and they all turned around. In a moment Paul was enveloped in greetings and hands slamming him on the back. He was pushed into a chair, a pint put into his hand. They seemed to be shouting at once, congratulating, chiding, insulting, wrapping him in Scouse good will and excitement. They were all so glad to see him he was embarrassed. It was as if he had just returned from a long exile in the States or Australia. In fact, he lived less than an hour away in a well-appointed detached house in a professional neighborhood in Chester. All the others lived a short bus-ride away: Michael, since his divorce, in a flat so small it was practically a bed-sit, the others in council-houses and semi-detacheds on the same streets where they’d grown up. Mike, of course, was Ritchie’s partner in the salon. Roger was a teacher, like himself, but in a school deep within the old city, a school filled with plenty of grubby, red Irish faces like their own had been, but also the black and brown faces of new immigrants’ children. Paul admired Roger - he had always been a man with convictions. He could teach in a better school, far from the decaying center, but he stayed because he believed he could make a difference there. And he was a published poet, a creator. Paul felt a pang - he wished that he had a talent like that. He’d tried painting when he was younger, but a good friend of his had been so much better that he gave it up. And he taught the great writers every day and knew that he could never match their words, so what was the point? Once upon a time he had even fancied himself a musician, but after some youthful playing in a beat combo, he’d given it over; after all, he had no musical training and the little tunes he often made up to amuse himself and his children didn’t amount to much. The kids had all had lessons, and he could doodle out a few pub songs and old Elvis numbers on the spinet, but... He put it out of his mind.

Roger and Mike were talking about their weekly poetry readings.

“Aye, Paulie, you ought to come out Friday - me and Rog do these comedy bits - along with the poems, of course,” Michael bowed slightly to Roger, who stared impassively through this wire-rimmed specs. Paul suddenly felt an odd jolt to his stomach, as if a goose had walked over his grave. Roger’s long, ironic face, the glasses, the half-smile - Paul saw Johnnie sitting there, in that same pub, in that same worn-down chair, smiling condescendingly at something someone else had said, looking sidewise at Paul, sharing his contempt with him like a drag on his ciggie. Paul felt ill. John was dead over twenty years now, but he could sense his presence elbowing through the room, filling this filthy, ruined city. He should have never come back, even for a night…

“I have to go,” Paul stood so suddenly his head was light.

“Here, now, wack,” Mike pulled him back down. “You look right spooked.”

“Brother, you are positively psychic.” He picked up his pint and tried to steady it against his lips.

“Don’t go now, Paulie - Willy’s supposed to turn up, and Adrian. You haven’t seen that lot in an age. We’ll have a right good bit of crac, just like the old days.”

Another man appeared and dragged up a seat. He was younger, but no longer young enough, dark-haired, with a pale, pointy face going fat around the edges. His piercing eyes glowered through thick, black-rimmed glasses that had been clumsily repaired at the edges. He carried a bulky, battered manuscript to his chest like a child, an assortment of pens jiggling against it in his breast pocket. He whispered urgently to Roger, who waved and nodded absently.

“Dec - meet Mike’s brother, Paul. Paul, Dec is a teacher, too, like you.”

Paul held out his hand, but the newcomer didn’t take it. Instead, he peered at Paul through those glasses, wary and hostile.

“Yeah. I’ve heard tell of you: the family success story. How’s the bourgeoisie treatin’ you?” Dec’s voice was soft, but the edge was menacing. Something about the fellow seemed ready to explode. He looked like the kind of office non-entity who turns up as a mass murderer one day on the front page of The Sun.

“Ah, I wouldn’t say that exactly - I get along, same as all of us, Mr...?”

“MacManus. Declan.”

“Well, Dec, I teach just English Lit out in Cheshire - I’m hardly a candidate for the next New Year’s List.”

Roger intervened. “Dec teaches computers at one of the technical schools. Wave of the future, computers. And I can barely get my old typewriter to work.”

“Computers, eh? I have a Mac at home. Handy for doing my notes and letters and things.”

“Well, I teach computer programming to a bunch of illiterates who can’t afford to have Macs sitting on their antique desks in their posh digs. Occasionally one of ’em even gets a job in an office that almost pays what they need to live on. Does my heart good when that happens.” Dec fumbled with a cigarette, offering the pack around the table, but pointedly not offering one to Paul. The hair on the back of Paul’s neck raised, like a challenged dog ready for a fight. He almost enjoyed the feeling.

Michael, leaned in between them, taking a ciggie from the pack. “Dec is a writer. A fine one. He reads with our lot every week.”

“Oh, and what do you write, Mr. MacManus?” Paul suddenly desired one of those cigarettes more than anything. Funny, he had packed that in years ago, but he wanted one just the same.

“Nothing that sells,” he intoned, ominously.

“Now, then, Dec - did that friggin’ thing come back home again?” Michael poked at the dirty manuscript. The man flinched, as if Michael had touched a broken bone.

“Aye. Today. The fourth time.”

“Wankers. Sod ’em.” Dec’s perambulating manuscript was obviously an old joke among the lads.

“It’s the friggin’ Capitalist Establishment. They hate hearin’ the Truth!” Dec’s voice rose about the dim. A few men at the bar and in the corner clapped their hands. Someone shouted: “Bring on the Revolution!” while another countered, “Bring on another round!” The bartender shot Dec a warning look and he sunk in his seat.

Michael leaned over to Paul. “He’s just trying to take the piss out of you, that’s all. That’s Dec. He’s really brilliant, ya know. A mad piss-artist.”

Paul stood up. “I think I had best be going - it’s a long drive... A long way to get home.”

Michael and Roger stood up. Paul put on his coat and nodded to the table. “I’m glad to have met you, Dec. I hope you have some success with your work. If Roger thinks you’re a good writer, then you are.”

“Yeah, why don’t you...” He stopped and looked up at Roger.

“Dec, I was hoping that Paul would come Friday to the reading. Why don’t you come and read those poems you showed me last week, Dec? The ones about being a child in Liverpool in the Sixties? I’m sure Paul would appreciate hearing them. He’s a Scouse, too, at heart - aren’t you, old man?” Roger looked at Paul, but took Dec’s arm and directed him towards another table.

“I might do,” he murmured, engrossed in his pile of ragged papers and his misery. He sat down in the corner, alone. Michael shook his head, but Roger watched him ruefully.

“Another talent destroyed by this fucking society,” he said, flatly. “There was a time I thought something was going to happen here - right here. In Liverpool - in England. You could feel it in the air: the music, the poetry, the energy... and then - I don’t know. Nothing. Destroyed entirely. Like our mate, there.”

Paul turned to the door, his scarf around his neck. “I was thinking the same - but of someone else,” Paul said.

Roger looked at him. “John,” he said. It wasn’t a question.

******************************************************************

Pulling up to the old former church hall in Woolton, Paul had a strong feeling of deja vu. Certainly, he had been there before, although he couldn’t remember the circumstance. Perhaps he’d played there with the beat group when he was a lad. Yes, he was sure of it. He could remember humping the equipment up those steps and through the hall door. Carrying in his amp, pieces of Tommy’s drum kit. Or had it been Pete? No, that was somewhere in Everton, another old church that looked like all the other old churches.

He couldn’t remember things anymore, not the way he used to. It seemed so long ago. Thirty years? More? He tried to recall whether Stu had still been with them then. But all he could see was John, in his black leathers, ciggie dangling from his mouth, ‘supervising’ the operation. And George, trotting back and forth, ever eager to please. Christ, he thought, George! How many years had it been since he’d thought of him? It must be twenty-five years since he’d left the ’Pool and gone to the States where his sister lived with her husband. Well out of it, he’d thought at the time. Paul wondered idly if he should have done the same. But he couldn’t complain - it had been different for him. Paul had had his father to push him on, and he’d gone back and gotten an education. George had a good mind, but not for school. There had been nothing here for him. He’d have ended up - like John? That was a chilling thought.

And what about himself? How had he ended up? Really? Funny, but he had never worried about himself. He had always assumed that he would do well. He knew he had the looks, the charm, and a brain on him. His old dad, and his mum before that, had instilled purpose in him, told him he could do anything, was made for something better than the common lot. And he had believed it. He charmed the teachers at school, just like he’d charmed the girls, and done well with both. He’d gone on to university and taken a degree. He’d married a Southern girl, a Sussex girl from a well-to-do family (her father was a solicitor), who was also a teacher. A charmed life, some called it. He fit in at all the affairs where everyone was from a posh school and had a job that wasn’t dependent on government grants. He could talk a good game about art and the latest plays and books - that was his specialty, as an English master. He could talk music, which used to be his passion but was now just another subject to bring up at a dinner table or drinks party. In his bespoke suits and designer shirts he looked as prosperous and sleek as any Cambridge grad whose father was a baronet. When he was younger - well, he’d been a good-looking bloke and he knew it well. Looks and the right bit of chat could take you a long way. No, he hadn’t gone to the bad like - like others had.

So why did he feel this guilt? As if anything could have saved John - as if the band they fooled around with, or school, or even his girl (Paul winced as Cyn’s worried, overly made-up face crossed through his mind) could have pulled him out of the gutter that was of his own making. Paul thought of the last time he had seen Cynthia, standing at the gravesite. He knew she was pregnant, too, that made it so much worse. Her bleached blonde hair had whipped around her face, the tears streaking her mascara down like wild animal tracks. Aunt Mimi had turned away from her - turned away from them all - blaming them. Blaming them. Paul could hear John’s voice in his head - had it been in that very pub, or one just like it somewhere in the city? - “I’m either going to leave this city fucking famous - or dead.” He’d meant it.

Cynthia had gone away somewhere; they later heard she’d married, but he never heard if she had the child or what happened to it. Paul couldn’t imagine her not having it - not Cyn - so somewhere out in the world John’s kid was going about his business, maybe unaware, or uncaring, about the crazy man, the fucking genius who had been his father - and Paul’s best friend.

Paul found it hard to get close to people after that. He had other friends, but not close ones. Ivan moved to the South and got into university, taking a degree in Classics; they soon lost touch. George finished his apprenticeship and moved on to America. Paul even felt distanced from his brother: Michael was so connected to the old city and Paul could barely stand to be there: every street, every barbershop, every roundabout was a cold memory. He was physically ill as he paused at certain crossings, felt a jolt as he saw certain buildings, the backs of young men, heard laughter - it was like being haunted. He flashed on the two of them, heads together in his dad’s old house, cradling their guitars or pounding on the piano after they’d skivved off school....

The hall was set up for the reading, but the turn-out was sparse, to say the least. The broken stage, some battered tables and chairs pulled up close, a tipsy-looking piano at the side, a bar area where a red-faced Irishman was pouring pints out of bottles - that was it.

“Yeah,” said Michael. “I think he’s the Rector! Old sod!”

“Not much of a crowd.”

“Oh, it gets real rowdy later. Actually, they have a fella who plays some music and the kids will show up and dance. Not much life in this old parish anymore, I’m afraid.”

“Not many poetry fans, either.”

Michael shrugged. “It’s early yet.” He guided Paul to the table Roger and Dec had claimed. It was prime territory: near the stage and the make-shift bar.

“Read me this one, Dec. You don’t need to go up on the stage.” Roger was shuffling through the scruffy sheaf of manuscript. The other poet bolted down his drink, stood, and took a deep breath:

“I feel such sorrow, I feel such pain,

I know I won’t arrive on time,

Before whatever out there is gone

What can I do? That day is done.

It’s just a promise that I made

I said I’d walk in her parade -

Hot scalding tears I thought would flow -

Still in my heart they’ll never know.

That day is done,

You know where I’ve gone.

I won’t be coming back:

That day is done.”*

“For Christ sake, Dec! You and the four line rhymed stanzas! You should be writing songs for Top of the Pops!” Michael was laughing as he reached for a ciggie.

“Take that back, you bastard!” Dec reached across the table for Michael’s neck.

“Here! The lot of youse will go out into the street in a minute!” The big Dubliner who had been minding the bar was between them immediately. “This ain’t the first time you fellas have tried to start it up here and I won’t have it! Jaysus! You poets are worse than the bloody bikers!”

Roger hustled Michael across the room, leaving the red-faced Dec to gather up his dirty pages. “Bleedin’ hairdresser... What does he know about poetry or anything? Huh?” Dec glared at Paul. “I suppose because you’re teachin’ at some poncey school that gives your brother the right to critique my work? Why do you come slummin’ around here, huh? I know your story, son. You left your mate high and dry way back when and he went to the bad. Got himself plugged trying to pull off a robbery for a couple of lousy quid. Knocking over a chemist shop with a bleedin’ comb in his pocket. I suppose you think you’re that much better than us all? Go back to Oxford, pretty boy. Or ex-pretty boy, I should say.”

In his confusion, Dec dropped one of his pens on the floor and Paul bent to pick it up. He reached out to return it and then stopped.

“It was a harmonica.”

“What? What did you say?”

“I said, it wasn’t a comb. It was his harmonica. It was in the pocket of his leather jacket. John didn’t know that the owner, a Pakistani, had been beaten up the week before. The man had an unlicensed pistol - old Army issue. John was angry - he’d just lost a lettering job at a sign company, his girlfriend was pregnant, he was trying to get a band together to go over to Germany and play some gigs. His aunt was refusing to give him any more money. He’d gotten 10 quid from me two days before to pay the rent and buy some food - it was all I had to spare from working and trying to go to university at the same time. I couldn’t give him any more....” Paul played with the pen, turning it over and over in his hand. “He wanted me to quit school and go back over to Hamburg with him. I said no - I had a chance for something else. I owed it to my father, to make something of myself. John said... He....” Paul stopped and stared, as if trying to pull a vision out of the air. “I don’t think the man was trying to kill him. He just fired out of fear. And John was doing it out of fear, too. He was like that - completely spontaneous. Spontaneous fear, spontaneous anger at the world. I don’t think he knew what hit him. I hope he didn’t...”

Dec sunk back down in the chair and they both sat silently for a while.

“I’m sorry. I just fly off sometimes. It’s frustratin’ - a frustratin’ life. I keep having flashes of what I could be - Sometimes I see myself in another life - doing something else. Sometimes I’m playing music, or reciting my poems, or - I don’t know. Sometimes it’s so clear: what might have been? D’ya know? It’s all a pipedream. Daft, dreams, right?”

“No, not daft at all. I have them all the time. Sometimes so strong they’re brighter than reality. I hear music and it’s as if I could reach out and touch it...”

“How do you touch music?”

“I don’t know. I’m soft, right?”

For the first time, Dec smiled. “Yeah, I’m one of those crazy men, too. Aren’t we all? That’s why we’re here, living in dreams.”

“You know, Michael was right about your poems - No, wait, I meant that in a good way. Songs lyrics can be a kind of poetry. I - we - John and I used to write songs in the old days. Bad songs, but we thought they were great. You might try putting them to music. You might make a great song out of the bunch.”

“I don’t know anything about music. And who would sing them? I’m no folk singer and these certainly aren’t material for Top of the Pops.”

“You could sing them yourself. Ever listen to Bob Dylan or one of those old boys? Hold it...” Paul got up and moved over to an old upright piano against the back wall. “Try this: ‘That day is done - that day is done.’” He played a couple of chords and noodled around the words of the poem. “Can you play a guitar?”

“I’ve fooled around a bit. My mates used to laugh at me for it. They called me ‘Elvis’ - the prats.”

“Well, “Elvis’ - my mates used to call ME ‘Elvis’! It’s a compliment of the highest order. Maybe we can work something out. It’s fun, really. A rush.” Paul began to play a few more notes, a bit of a melody that came to him sometimes.

“That’s pretty good. You can really play that thing!”

“I used to be good on the guitar, too - they kept trying to lumber me with the bass, but I loved messing with the guitar.” He played another figure on the old piano. “Man, this needs a good tuning.”

Michael was suddenly standing next to him. “Hey! It’s Burt Bacharach or Henry Mancini or one of that lot! You getting into the music again, Paulie? He’s great, really. And I’m not saying that just because he’s me older brother and might cripple me!”

Paul played a bit more. Roger came over and nodded. “I like your tunes, old son. Are you and Dec going to hook up and make us some hits, then?”

“We might!” Said Dec. They turned and looked at him with surprise. “We might, just.”

“What’s that you’re playing, then, Paulie?”

Paul smiled. “Just something I’ve fooled around with. I call it ‘Scrambled Eggs.’”

“Always the joker.”

“You’ll see. You’ll see. It’s never too late to live your dream. Don’t leave until yesterday what you can do tomorrow. Right, Dec?”

“That makes no sense at all.”

“It will, son. It will.”

####

(* ©McCartney/MacManus 1989)

©Gael McGear Sweeney 1999