electric youth

Pretty awesome scaffolding around the shell of the old Colegio de los Escolapios de San Antón, a massive building taking up most

of a huge city block in the Chueca-Malasaña area of Madrid. Built during the last third of the XVIIIth century, the building (future home of

the Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid) has served as a leper's asylum, a convent and a catholic school over it's 300 year history.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) the school was converted into San Antón Prison (officially registered as 'Prisión Provincial de

Hombres número 2'); thousands of conservatives were imprisoned there, and a good number of them ended up forming part of the

collective massacred in Parcuellos del Jarama from 7 November to 4 December 1936. It went back to being a school after the war, and

continued to serve as such until 1989. It was abandoned in 1995 and was acquired by the city in 1999. It is currently in the process of being

restored and will eventually not only serve as home to the COAM, but also house yet another children's school, an indoor community

swimming pool, a public library, community center for the elderly, and a shitload of ghosts - nuns, prisoners, and angry little kids.

Les Demoiselles de Guernica, it would seem.

(El Tono on the left.)

(Pirates off to the right!)

(Another El Tono.)

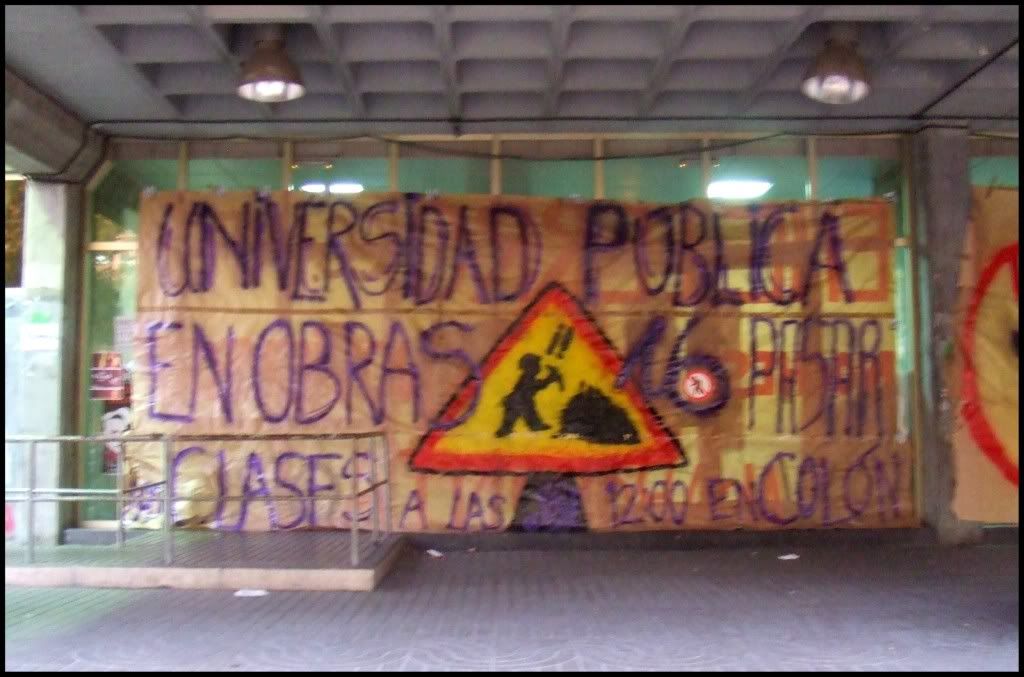

(Seen at the UCM.)

Last Thursday, the kids went on strike for no real reason.

The grievance listed was the Bologna Process, project which regulates education

at a trans-European-Union level and makes it easier to convalidate fields of studies / grades

between one country and another, theoretically making it easier for EU citizens to move seem-

lessly between member nations. While Spain will no doubt botch this up magnificently (the ent-

ire project necessarily involves levels of bureaucratic maneuvering lightyears away from what

this fantastically backward nation can ever handle), and the education system will no doubt

decline significantly because of it (they're removing an entire year from most study plans,

and making half of the remaining classes "virtual" - something that should provide more than

a few chuckles, considering how HOPELESSLY behind we are in all things technological), the stu-

dents aren't protesting about this. In fact, no one is actually sure why they're protesting at

all, given it won't affect any of us - the first to endure it will be the graduating class of

2015. Moreover, the Bologna plan was passed last year; while it might have made sense to strike

while it was still in legislation (and thus possible to alter, or stop altogether), we're now

talking about a ratified, established law against which no one said anything previously - sudden-

ly deciding to rescind it would completely discredit the Government (which is in no position to

allow for any sort of polemics, given the economic crisis - highlighted in last week's issue of

The Economist) and, besides, there isn't anything REALLY [atleast in their warped context of things]

wrong with it. Still, the school is a spiderweb of highly politicized student unions directed by shady

'caciques' {bosses, a la Boss Tweed, who control the university's political machine}, and for

whatever reason (probably not having received the expected back-scratching), the caciques are

out to pressure 1. the Complutense's rector, & 2. the reigning government, so they've united

and gone on strike. This led to the occupation of certain buildings, sleep-ins, and attempts to

bar students from entering, results of which were violent altercations on Thursday morning.

In the School of Philosophy, they blocked off entire halls and classrooms with boxes, barricades

made of chairs, and elaborate tripwires made of duct tape and chunks of trash.

Meanwhile, at the School of Journalism they settled for blocking off the entrances with enormous signs.

I didn't have class until the evening, but the Journalism Gays informed me that several kids who tried

to enter in the morning were actually attacked by strikers. Being tough bastards, tho, the J-Gays got

through ("Les dije que si no me dejaban pasar les iba a dar dos ostias"), only to have to climb up several

staircases full of tripwire before reaching their first period class on the fifth floor. Several professors

ended up showing solidarity with the strike breakers, and they nearly came to blows with striking students,

forcing their way through doorways to let students come in to the building and on to their classes.

This being Spain, the strikers stuck around through some of the morning, began dispersing within

the first hour, and were ultimately all gone by shortly-past-noon. Sure, they're all about fighting

injustice - but staving off their own hunger is more important, and lunchtime (plus the requisite

afternoon siesta) are things against which they could never strike. By the time I showed up for class

that afternoon, the morning's shenanigans were long settled, and what remained were mere ghosts of

yet another pointless strike past.

Peace, indeed, had returned to the Ciudad Universitaria.