nafarroa, naba: tierra llana rodeada por montañas

While in Pamplona I took a day to trek out to the village of Berasáin to visit some old, very close family friends. This implied leaving the provincial capital and hiking some 20-odd kilometres through some of the most gloriously peaceful and ridiculously countryside that northern Spain has to offer - and that's really quite alot to say. So, here's 20-odd kilometres of hiking through my birth-region of middle Navarre, specifically the villages of Aizoáin, Berriosuso,

Ollacarizqueta, Marcaláin, Amaláin, Eguaras and Aróstegui, before finally reaching the valley of Atez, wherein one finds Berasáin.

(Typical example of proud-and-sturdy Navarro-Basque architecture, which generally involves the use of stone and intricately carved wood detailing.)

For centuries it's been standard for the villages of Navarre to list the name of the burg in the most prominent edifice upon entering the place, regardless of it being a government building, a private house or a classic barn, oftentimes upon ceramic tiles and accompanied by the Royal Shield of Navarre. On account of the Kingdom's early participation on the side of the rebellious Nationalist troops in the Spanish Civil War (the uprising actually began in Pamplona, a result of the long-rooted ultra-traditional Carlist traditions in the area), in 1937 Franco awarded the Cruz Laureada de San Fernando to the geographic entity of Navarre for it's "heroic labour", and from then on until 1981 the Shield appeared ensconced in laurels and accompanied by swords. Many villages still feature name plaques with the old francoist Cruz Laureada Shield (tho the 1910 shield appears in this particular case).

Navarra translates to "fertile land surrounded my mountains" in antiquated basque; it's etymology is remarkably

accurate, given theprovince is a mindblowing series of deep, green valleys separated by breathtaking mounts.

And within the valleys? Cluters of ancient houses that constitute villages, sometimes made up of a single family estate that has come to be rambling over the centuries.

Marcaláin is one of the bigger villages: it's made up of about 10 houses. Here, the town hall doubles as the local hospital.

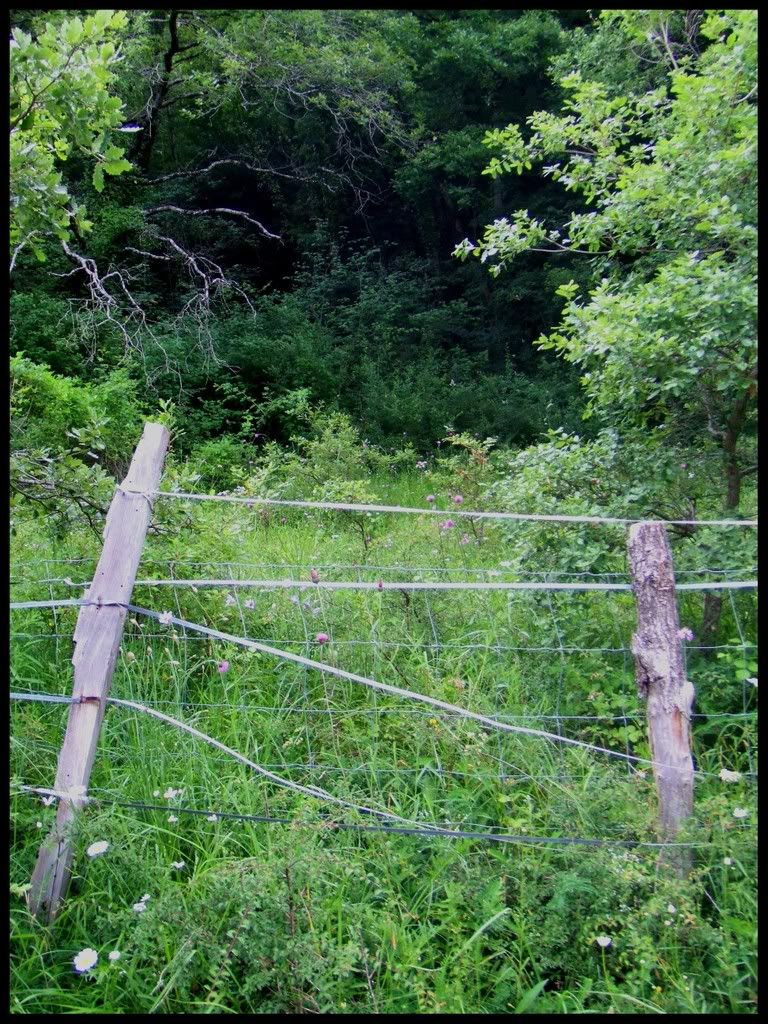

I tried to take a shortcut at the bend right ahead of here, climbing up a very steep cliff, ripping pants and shirt with all

imaginable thorns and rubbing myself up with some really interesting itchy ivy. It probably wasn't really worth the

trouble, but it was fun and still managed to shave five minutes off the walk - regardless of that not really mattering, given I was making good time and it seemed I'd more than arrive by lunch.

View from the other side of the climb.

Further on, I ran across a herd of wandering pottokas, miniature horses native to Navarro-Basque section of the Pyrenees. And they were fucking adorable.

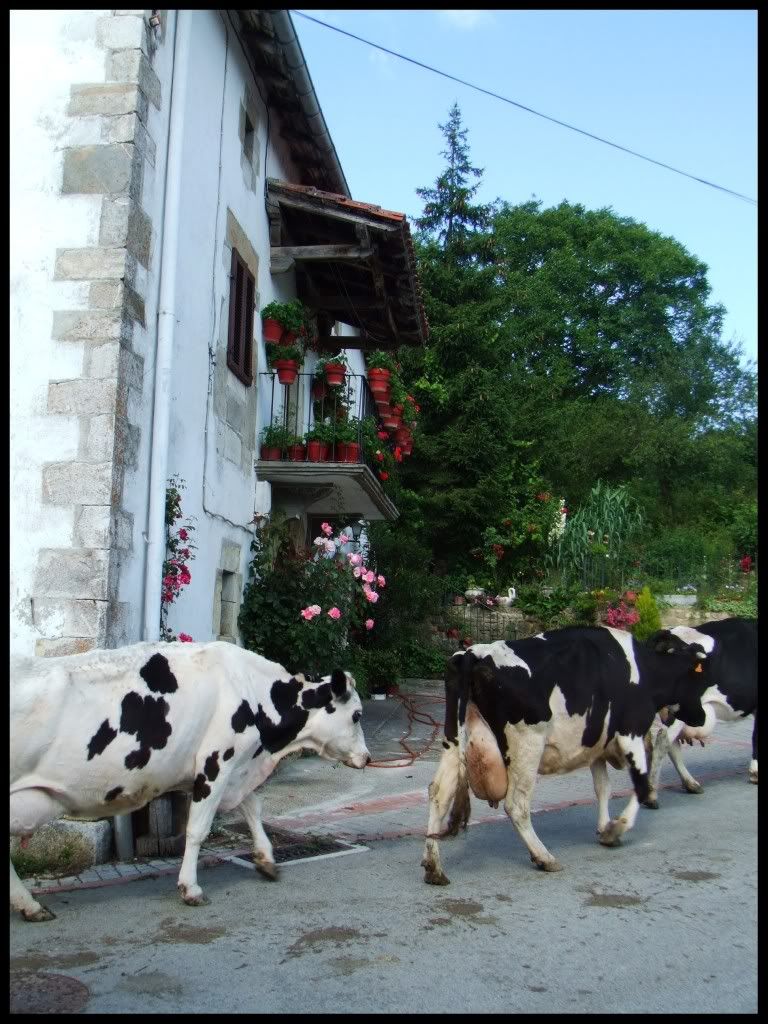

And then there were cows.

And they were fucking adorable, in all of their bovine wonder, as well. (I get why Hera's commonly used epithet of βοώπις, or cow-eyed, was a compliment.)

Then onto Eguaras...

For those who have never met her, I grew up going to school with an amazing girl named Ashley Arostegui, and

so figuring out her last name's namesake village was on the way, I decided to take some pictures of the place. The place, by the way, had it's name spelt atleast four different ways on the signs pointing to the town, round which some minor roadwork was being undertaken.

The tower belongs to the medieval church, one of which there is in every single one of these villages, regardless of the number of inhabitants. For centuries on end, the norm is that a single priest is appointed to each valley, and he spends the week traveling from village to village and giving mass on different days. The key to village church is handled in the same manner as the village mayoralty; the responsibility of keeping the key and opening the church rotates from one family to another each month, and the position of mayor likewise rotates each year. The village councils are composed of one representative from each family, and between them they settle matters of village taxes and so-forth. The village mayors, in turn, get together once a year to elect a valley mayor, who represents them before a larger consortium of valleys, which in turn elect provincial representatives.

Those dogs barked at / chased me more out of habit than any firm conviction. I do not joke when I say that no Navarrese house seems to be able to comfortably exist without a couple of vaguely apathetic guard dogs. As such, as one passes through the villages one inevitably encounters random, unenthusiastic and hugely ineffective dogs that inspire more pity than fear.

Alot of these villages have reinvented themselves in the face of the post-war urban settings by focusing on rural tourism and local crafts. This house apparently combined both, serving as both a countryside inn and a carpenter's workshop.

These sorts of places are pretty amazing to sleep in, given how perfect the silence is at now, how cozy everything feels within those big stone houses, and how amazing the stars in the sky look away from the distracting lights of the city.

And so that was Ashley's ancestral village.

En route to Berasáin the family actually ended up finding me on the road; they had gone

to fetch me from a bus stop, several villages to the north, never expecting I'd walk up directly from the capital in the south.

The family lives in a farm house older than Europe's knowledge of the American continents; their people have probably been in the valley for atleast a millenium (Basque descendants), but this particular incarnation of the house began to be built upon the foundations of previous ones around the early 1400's.

Blanquita [seen here] is the mother. We came to know the family by way of Pastor, a priest who was always a close family friend and basically my godfather. Pastor was director of restoration for the properties of the Catholic Church in Navarra, and much of his work consisted in traveling to the furthest reaches of the province and painstakingly restoring the most neglected buildings. Just taking in consideration that every one of these villages has their own church, and every single one of them is atleast 200 years old begins to put into perspective the massive task assigned to him, and the value of the projects to which he had to attend, given that even if these were just humble parish churches, they often held treasures, not only in terms of architectural design of religious relics, but also the illustrious bones of all sorts of kings and notable

figures (like those of Cesare Borgia, upon whom Machiavelli's Prince was modeled, who was abruptly slain during a skirmish in a village a bit south from here shortly after the death of his father, the Pope).

At any rate, villagers often helped in the restoration work, and while Pastor was working on the local church in Berasáin Blanquita's husband lent a hand. One day this fellow rushed over and began to do some work before Pastor arrived (as he often worked on several buildings at the same time, while still serving as the traveling priest for a number of villages south of Pamplona); while essentially doing the work that Pastor would have done upon arriving, the ceiling collapsed, the man fell and was immediately crushed to death. Blanquita's son Aitor was 4 years old at the time, and she was six month's pregnant with her daughter, Ana. Pastor took it upon himself to essentially fill in for the father in whatever he could, serving almost as

a father-figure to the children and passing whatever time he could with them.

It was such that when he came to know my family he was already well-entwined with theirs, and so, likewise, we became entwined with them, and thus since before my own birth, we've well-known them, and they us.

(They had new-born chicks hanging about in the kitchen.)

Pimientos al Piquillo - very typical in Navarra.

Blanquita's husband grew up in that house, literally across the courtyard, and when she married he moved into the larger house.

After lunch we took a drive through a couple of the nearer valleys.

Returned to the house, now.

The seal on the side of the house commemorates the 1550 addition to the house, which added a third floor.

The side door, meanwhile, used to be the main door; I didn't get a detail shot of it, but the keystone commemorates the original, XVth century foundation.

Blanquita's brother, looking at...

...their standard-issue, cowardly / apathetic guard dog. That chain goes for miles, but he did not leave his shack while I was about, and I later learned that he is the very definition of useless. The used to have geese; they were eaten. They had ducks once, too; those also are gone. It wasn't the dog - it was the fox, the fox and the wild cats. Was the dog on guard? Certainly. He's just useless, that's all, and that's why the chicks have to be inside.

The in-house dogs, meanwhile, are very friendly, but too domesticated to be any more use against the usual countryside threats.

But, ah, what countryside...

And what for a splendid house.

(And what for a neighbour's house, as well.)

And back to the contemporary front door, the 1793-1796 stones commemorating the house expansion by ancestor Domingo. So. Much. History. And to think what ridiculously happy times were spent, there.

A bit later, the cows were brought in. It used to be that Blanquita's family owned great masses of cows, and they were brought in and stored in the barn beneath the house (which, mind you, greatly reduced heating expenses), but given Blanquita's age and her son Aitor's interest in architecture, and Ana's ocupation as a hairdresser, it was no longer terribly practical. They were sold off to some great landowner from a neighbouring valley, a fellow who now owns most all the cows in the region, and pays comfortable amounts to rent Blanquita (and many other's) farm lands, upon which the cows graze comfrotably.

Blanquita's brother, a lifelong farmer (now retired, on account of his heart condition) who enjoys a comfortable life with the income generated by renting the lands is nonetheless naturally furious in the face of these conditions. Indeed, the idea of the cows being sold off and then brought back to graze on the same land, why it's almost too much to bear. Besides, everyone knows that high and mighty landowner made the fortune he used to buy the cows via decades of smuggling goods back and forth across the French border, using hidden passes in the Pyrenees.

(As if we needed his dirty money.)

Anyway, cows.

Inside the barn...

...CHICKENS.

Aitor, who is a master woodworker and quite the painter, has painstakingly restored the house over the past decade. One of his major projects was restoring the XVIth century kitchen.

The region has a rich tradition history of witchcraft-related folklore; the house itself is not exempt, there supposedly having been reunions of witches in this very kitchen in centuries past.

Witches were not the only one's to camp out in the house at one point or another. During the Carlist Wars Don Carlos, the absolutist pretender to the throne, slept here (with his entourage) for several weeks; he left them his personal silverware as a gesture of thanks. In contrast to his conservative anecdote, Aitor later brought out an old, rusted rifle - left there by one of many antifascist macquis (anti-Franco guerilla warriors) who sought food or medical aid at the house during the years following the Spanish Civil War, when such an act of charity could have meant the execution of the entire family as traitors. These days, it even continues to be a stop on the annual rambling tour of the image of St. Miguel of Aralar (and his retinue of varied members of the clergy) throughout the Kingdom of Navarre.

As it has been over the past centuries, the family and their house continue to offer a place of refuge for everyone, indiscriminately.