Noir is like an addiction.

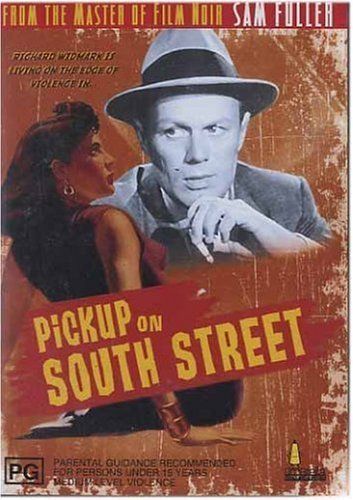

Pickup on South Street

Director: Samuel Fuller

Starring: Richard Widmark, Thelma Ritter, Jean Peters, Richard Kiley

1953

Film noir as interpreted by Samuel Fuller. As if noir wasn’t dirty, gritty, and grimy enough, Fuller has to take his pulp style, his unabashed love of the lowlife, and overlay it with the world of film noir. What results from this mashup is a noir that feels a bit different, grittier, danker, sweatier than others. Which, of course, makes for a perfect noir.

Richard Widmark is Skip McCoy, a pickpocket or “cannon,” who unwittingly lifts sensitive government microfilm in the middle of it being passed from traitors to communists. The police are on his case, the government is on his case, and the traitors are on his case. Everyone wants the film back. What’s a regular ole pickpocket to do?

What elevates Pickup on South Street from a more laborious 1950s Anti-Communist propaganda is the character of McCoy. Frankly, he couldn’t care less about either side. It’s not that he particularly likes the commies, but he’s far more interested in getting as much money or as many favors out of each side than he is doing right by his country. As he says to the exasperated police detective, “Are you waving the flag at me?!” Whichever side can offer him the better deal is the one he’s more interested in.

Apart from McCoy’s indifference is his sheer character. Widmark is brilliant in the role. He is a lowlife, a simple crook, a three-strikes hoodlum who knows that one more time being caught red handed means life in prison. What’s phenomenal, however, is Widmark’s range. When talking to the cops, he is cocky, arrogant, cynical, rebellious. When talking to Candy, he is guttural, primal, sexy. When dealing with the commies, he is down to business, cutthroat, practical. And when talking to Moe (Thelma Ritter), the closest thing resembling a maternal character, he is sometimes petulant, at other times loving and obedient. Widmark manages to swing from vicious conniver to angry lover to quiet grief with the deftest touch. I have not seen a great deal of his work, but it is difficult to imagine him in a finer performance. Only in noir could such schizophrenic mood shifts seem both plausible and ordinary.

The eyes. The shadows. This shot exemplifies this film.

Throwing a monkey wrench into his extortion deal is the character of Candy, played by Jean Peters. It is Candy whose pocket McCoy picks, as Candy is being used in the drop by her ex-boyfriend Joey (Kiley). While Candy is ignorant of the commie scheme - she’s more being used by her ex-boyfriend than anything else - she must also try to get the film back from McCoy, which of course leads to complications, given that she is truly jello on springs. If there was ever an actress more confident in her sexuality than Jean Peters is in this role, I’d love to see it. She simply exudes sex, and when Joey asks her how she got the film back and she responds, “How do you think?” it takes a very small stretch of the imagination. Peters is constantly sweating, giving her that look of just having had a go with someone in the back room. Her lips, plump and pouting, squinty eyes, and a husky voice reminiscent of Barbara Stanwyck paint her as no angel. In an article about the film by Luc Sante (included in the always fantastic Criterion edition of the DVD), he describes her as “awe-inspiringly ripe - you imagine wardrobe having to gaffer-tape her dress every morning, to keep her from bursting out of it.”

I mean honestly! How much more raw can you get???

Apart from Widmark and Peters, it is Thelma Ritter who provides the emotional core of the film. She plays Moe, a stoolie who deals in information to whoever is willing to pay for it. Ritter made a career of playing the same role in slightly different variations, but this one is above and beyond. Moe is sad and sympathetic, despite the fact that she will pander to pretty much anyone for the right price. The reason for her extortion is to buy a nice headstone and plot for herself in a private cemetery; her greatest fear is anonymity in death. This kind of morbid awareness is made even more poignant when she is brutally gunned down in easily the most emotional scene in the film. When McCoy hears of her death, his face falls as he realizes that Moe will now face her worst fear, as her coffin is unceremoniously carted off to a criminal cemetery. Ritter rightfully garnered one of her six Oscar nominations for her role as the world-weary Moe, and almost manages to steal the show from the other stellar performances.

Look at how small and run down she looks here!

There is something very Fuller about the film. He is obsessed with almost comical close-ups, pushing the camera in so far to his actors’ faces that every line, every wrinkle, every bead of sweat is visible. This, along with the less than flattering lighting in many of these shots, seems to transform the actors from characters to caricatures, making each of them grotesque absurdities. The paranoia laced throughout the script is also classic Fuller, a theme to which he would return in films like Shock Corridor. The character of Joey, a traitor trying to peddle his wares to the commies, is a man driven insane by his paranoia. He is constantly looking over his shoulder; at times, he is simpering and weak, at other times, he is violent and dangerous.

Despite all the wonderful visuals, what strikes me most about the look of the film is one set in particular - that of McCoy’s “house.” The film is set in New York and deals with the lives of New York lowlifes. However, there is precious little in the set of the film that evokes that classic New York City street grit. McCoy’s house, where a number of significant scenes take place, is a wooden shack off the docks held up over the water by stilts. It’s so bizarre a setting, so very anti-New York (anti-everything, really), that it’s a jar to see it the first time. Perhaps it is meant to be so unsettling, to remove the viewer very forcibly from the story. And yet it is so far off the deep end (pun intended), so completely ludicrous, that it seems to fit right in with the more than off-kilter world of Samuel Fuller. It is perfect in its absurdity.

While I find the ultimate ending of Pickup on South Street to be a bit too pat for my taste, it is nonetheless a fantastic entry into the gloriously gritty world of film noir. As I have said before, when I first watched the greats of noir, I had little appreciation for them. Over time, however, noir starts to fester; it gets into your bloodstream, and soon, it’s your preferred genre. Unsurprisingly, my most recent encounter with Pickup on South Street had me falling far more deeply in love it than the first time I saw it. Solid, solid noir.