#1305-1310 - Some Marine Inverts

#1305 - Pseudorhiza haeckeli - Red-netted Jellyfish

A fairly hefty jellyfish, more common in the open waters off Australia’s coastlines, but often enough brought in-shore by prevailing winds.

Often found with amphipods and parasitic anemones attached, and very often accompanied by a school of small fish, as here.

#1306 - Catostylus mosaicus - Jelly Blubber

A large, very common coastal jellyfish from the Indo-Pacific, frequently swarming in estuaries. Also known as the Blue Blubber, but can be a range of colours such as brown above, depending on which symbiotic algae is living in its tissues. Grows to up to 45cm across, and mostly harmless. Ice packs suffice if you do somehow manage to be stung badly enough to get a reaction.

#1307 - Chrysaora kynthia - Australian Sea Nettle

Photos from the Perth Snorkelling group.

A common pest to swimmers around Perth, when the temperature and wind conditions are right (although there seems to be debate about the legitimacy of the species). Like other Chrysaora species, possesses a powerful sting - people are advised to wear protective clothing if they’re around, or not go swimming at all.

The sting creates raised red weals may occur, the redness may spread, but should disappear in 2 to 3 days.

First Aid - Do not treat with vinegar. Remove any tentacles from the skin using tweezers or a gloved hand. Neutralise sting with a paste of bicarbonate of soda and seawater, if unavailable wash the area with seawater. Apply cold pack, and possibly a pain relieving cream, to the affected area for pain relief. This may need to be repeated for some weeks if the itchiness persists.

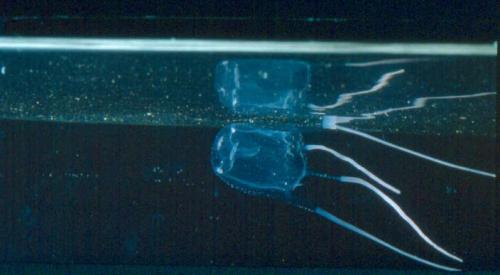

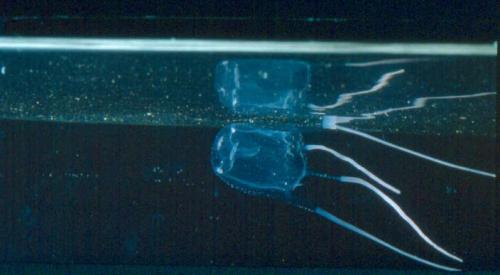

#1308 - Carybdea xaymacana - Southwestern Stinger

The photo is from online, but when my brother was visiting the harbour at Fremantle and described matchbox-sized jellyfish with four tentacles, there’s not much else is could be. Southwest Stingers (Fam. Carybdeidae) are cubomedusans found in temperate Australian waters, but unlike the justly infamous box jellyfish, sea wasps, and Irukanji of more tropical shore, they aren’t horribly dangerous. They’re merely dangerous enough that anti-stinger suits are highly advisable (and a necessity Up North).

Despite being spineless, brainless, and lacking any visible means of support, cubomedusans are rather more capable then your average bad boyfriend. They can deftly manoeuvre around obstacles, hunt prey, swim towards artificial light and avoid stormy weather by entering estuaries. This, despite lacking brains or even any tissue to make a brain from. They DO have 24 eyes, though, with 4 being remarkably sophisticated for a jellyfish, complete with lenses. Most of the thinking about obstacles appears to take place in the eye clusters.

Being stung by other box jellyfish is life-threatening and frequently fatal, with symptoms including impeding doom and multiple brain haemorrhage. With the Southwest Stinger, the initial sharp pain fades to itching within a few hours, and the weals rarely last more than a few weeks. First Aid includes pouring vinegar over the affected area to deactivate unfired nematocysts. Remove any tentacles from the skin using tweezers or a gloved hand. Apply cold pack, and possibly a pain relieving cream, to the affected area for pain relief. This may need to be repeated for some weeks if the itchiness persists.

#1309 - Neis cordigera - ‘Shopping Bag’ Comb Jelly

Photo by Barbara Davenport.

After a bunch of species that can variously annoy you or kill you in minutes, now for something completely harmless - unless you’re another comb jelly.

Neis cordigera is a large predatory ctenophore native to Australia’s coastal seas. It’s up to a foot long, with two fins at the trailing corners, and a wide flat body. When hunting other comb jellies it cruises up to them, unzips its mouth, and engulfs them whole. It then uses internal macrocilia as a biological chainsaw to carve them into chunks. If it’s only a young Neis, and is hunting prey larger than it, it bites off pieces.

They can have blue, pink, or orange colouration, but the case of the ones the Perth Snorkelling group was finding around Coogee, be almost clear.

There are very few photos of this ctenophore online, and only one drawing on the Atlas of Living Australia. Just goes to show you how useful citizen science and interested amateurs with modern cameras can be.

#1310 - Tosia sp. - Biscuit Star

Not quite a Magnificent biscuit star, but still a fine species. Not the kind of animal one might expect on Australia’s southern coastlines, but not uncommon in shallow water. Either Tosia australis, the Southern Biscuit Star, or Tosia neossia, which I suspect means New Biscuit Star or something similar, since the species was recently split into two based partly on reproductive strategy. T. neossia spawns in late winter and broods the embryos in depressions under the adult body. T. australis doesn’t.

A fairly hefty jellyfish, more common in the open waters off Australia’s coastlines, but often enough brought in-shore by prevailing winds.

Often found with amphipods and parasitic anemones attached, and very often accompanied by a school of small fish, as here.

#1306 - Catostylus mosaicus - Jelly Blubber

A large, very common coastal jellyfish from the Indo-Pacific, frequently swarming in estuaries. Also known as the Blue Blubber, but can be a range of colours such as brown above, depending on which symbiotic algae is living in its tissues. Grows to up to 45cm across, and mostly harmless. Ice packs suffice if you do somehow manage to be stung badly enough to get a reaction.

#1307 - Chrysaora kynthia - Australian Sea Nettle

Photos from the Perth Snorkelling group.

A common pest to swimmers around Perth, when the temperature and wind conditions are right (although there seems to be debate about the legitimacy of the species). Like other Chrysaora species, possesses a powerful sting - people are advised to wear protective clothing if they’re around, or not go swimming at all.

The sting creates raised red weals may occur, the redness may spread, but should disappear in 2 to 3 days.

First Aid - Do not treat with vinegar. Remove any tentacles from the skin using tweezers or a gloved hand. Neutralise sting with a paste of bicarbonate of soda and seawater, if unavailable wash the area with seawater. Apply cold pack, and possibly a pain relieving cream, to the affected area for pain relief. This may need to be repeated for some weeks if the itchiness persists.

#1308 - Carybdea xaymacana - Southwestern Stinger

The photo is from online, but when my brother was visiting the harbour at Fremantle and described matchbox-sized jellyfish with four tentacles, there’s not much else is could be. Southwest Stingers (Fam. Carybdeidae) are cubomedusans found in temperate Australian waters, but unlike the justly infamous box jellyfish, sea wasps, and Irukanji of more tropical shore, they aren’t horribly dangerous. They’re merely dangerous enough that anti-stinger suits are highly advisable (and a necessity Up North).

Despite being spineless, brainless, and lacking any visible means of support, cubomedusans are rather more capable then your average bad boyfriend. They can deftly manoeuvre around obstacles, hunt prey, swim towards artificial light and avoid stormy weather by entering estuaries. This, despite lacking brains or even any tissue to make a brain from. They DO have 24 eyes, though, with 4 being remarkably sophisticated for a jellyfish, complete with lenses. Most of the thinking about obstacles appears to take place in the eye clusters.

Being stung by other box jellyfish is life-threatening and frequently fatal, with symptoms including impeding doom and multiple brain haemorrhage. With the Southwest Stinger, the initial sharp pain fades to itching within a few hours, and the weals rarely last more than a few weeks. First Aid includes pouring vinegar over the affected area to deactivate unfired nematocysts. Remove any tentacles from the skin using tweezers or a gloved hand. Apply cold pack, and possibly a pain relieving cream, to the affected area for pain relief. This may need to be repeated for some weeks if the itchiness persists.

#1309 - Neis cordigera - ‘Shopping Bag’ Comb Jelly

Photo by Barbara Davenport.

After a bunch of species that can variously annoy you or kill you in minutes, now for something completely harmless - unless you’re another comb jelly.

Neis cordigera is a large predatory ctenophore native to Australia’s coastal seas. It’s up to a foot long, with two fins at the trailing corners, and a wide flat body. When hunting other comb jellies it cruises up to them, unzips its mouth, and engulfs them whole. It then uses internal macrocilia as a biological chainsaw to carve them into chunks. If it’s only a young Neis, and is hunting prey larger than it, it bites off pieces.

They can have blue, pink, or orange colouration, but the case of the ones the Perth Snorkelling group was finding around Coogee, be almost clear.

There are very few photos of this ctenophore online, and only one drawing on the Atlas of Living Australia. Just goes to show you how useful citizen science and interested amateurs with modern cameras can be.

#1310 - Tosia sp. - Biscuit Star

Not quite a Magnificent biscuit star, but still a fine species. Not the kind of animal one might expect on Australia’s southern coastlines, but not uncommon in shallow water. Either Tosia australis, the Southern Biscuit Star, or Tosia neossia, which I suspect means New Biscuit Star or something similar, since the species was recently split into two based partly on reproductive strategy. T. neossia spawns in late winter and broods the embryos in depressions under the adult body. T. australis doesn’t.