ten good things (longest blog post EVER)

i've been meaning to write this for about a month. which hopefully explains its ungodly length. truth be told, i've been pretty busy for an unemployed dude. i do want to write on here more often though, for realzzz...

10.

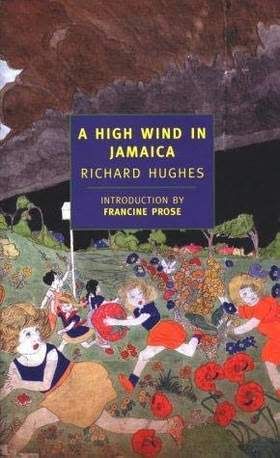

richard hughes' novel a high wind in jamaica engenders the exact breed of surrealism i like best... its setting (initially a jamaican plantation destroyed by a hurricane, later a pirate ship!) is bizarre but also plausible, and its uncanniness owes more to thought out, atmospheric descriptions than to sudden disruptions in logic. in fact it's the logic itself that supplies its weirdness-- the way it naturalizes unlikely situations. its spookiness sets in as one page leads casually to the next. were it not for its occasional-- and totally inexcusable-- bursts of racism, i'd even say it rivals my other favorite classic-of-understated-surrealism: bruno schulz' the street of crocodiles.

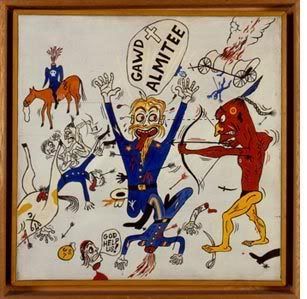

like the henry darger painting that graces its cover, jamaica is largely a book about child sexuality. but unlike darger's constipated blend of innocence and repression (brilliant as it may be), hughes' handling of the subject is lucid and respectful. contrary to what i may have looked like in 1993, i've never been a pre-pubescent girl, personally. and i'd wager that hughes hasn't either. but as far as i can tell, he paints a convincing, comprehensive portrait of how that might feel, hormonally-- minus much of the lechery such question-raising might imply.

hughes isolates the tension between playfulness and learned morality with astounding accuracy. the book's precocious central character (emily) emerges at the tail-end of childhood's most limitless pleasures. she is solipsistic and confident-- almost to the point of megalomania. one of the great surprises of the book is the way that hughes reveres her confidence-- there's something convincingly utopian about her ignorance of gender norms, her willingness to follow her obsessive inclinations, and her ability to make a game out of everything. her "sexual awakening" occurs alongside her instinctual bravery in a variety of ways, most notably in her often dangerous interactions with adult men. hughes foreshadows the barriers, frustrations, and new pleasures that might soon arise for her as a growing person. these real-life dangers are rendered with a deep respect for the curiosity they provoke within her (and even, ickily enough, within the "pirates" aboard the ship). the taboos that arise are handled with an unforgiving investigative integrity, but there's a distant gentleness to hughes' writing as well. i found myself able to find parallels between emily's adventures and my own childhood-- particularly those weird, pre-"gendered" moments that society at large would rather not discuss. and it reminded me of the strange balance of confidence, insecurity, sexuality and socialization that determined my own creative abilities, for better or worse.

9.

my growing obsession with apocalyptic imagery lead me to go on a little kick with only-man-left-on-earth movies. it's a fun genre, but i didn't expect to stumble upon any really great films, quite honestly...

i rented ranald mac dougall's 1959 film the world, the flesh and the devil expecting little more than to enjoy the novelty of its premise: the human race has inexplicably vanished overnight, and the last living human is portrayed by harry belafonte.

as silly as this may sound, it's a remarkably sophisticated film in a number of ways-- and one that i think has taken on new meaning with age (as i will get to in a minute). first and foremost, there's the fact that it was made in 1959. the only major entry into the genre at that time was stanley kramer's dull, self-important cold war dystopia on the beach... and even that was released (more or less) concurrently. so-- to the best of my knowledge-- we have the world (and the twilight zone, which also began airing in '59) to thank for our first taste of the eerie, abandoned crane shots, schematic storylines and bitter cultural allegories that would define the genre from night of the living dead on up through 28 days later. hell, it was almost literally remade in 1985 as geoff murphy's the quiet earth, right down to its handling of miscegenation as a central topic.

... which brings us to the strange fate of the film itself. from the tiny bit of cyber-sleuthing i've done regarding the film, i've gathered that belafonte distanced himself from the project upon its release. he thought the film did little justice to the interracial romance that comes to occupy the center of its story, as his character comes to find that there is also a white woman (and later, a white man) who has survived the tragedy. and its true-- it totally chickens out when it comes to depicting their relationship physically.

but the nice thing about art-making is that mistakes can turn out to be assets. in 1959, there was undoubtedly a need to transgress the taboo of race-mixing on screen. the mere act of depiction could be sharply confrontational and politically useful. in 2007, explicit depictions often deaden my viewing experience. taboos and transgressions are par-for-the-course, and uninspired filmmakers litter the screen with them as a substitute for an active, engaged experience. there is a scene about halfway through the world where sarah (inger stevens) asks ralph (belafonte) to give her a haircut. this seemingly banal event points allegorically to all the simmering sexuality mac dougall doesn't quite have the guts to depict. upon its release it was undoubtedly a cop-out; in 2007, it's not only heartbreaking, but sexy as hell. as the mood moves from confrontational to confusing, from bawdy to malevolent-- its hayes code inheritance becomes the issue at hand. my initial titillation deepens considerably, becoming inseparable from its more general sense of melancholy. society might have broken down completely, but somehow its ideology survived. the miscegenation taboo almost zombifies the characters. it looms over their actions, and they become entranced by it. sarah and ralph wander their scorched earth like birds that can't quite hop out of their cages. what begins as a flirtatious and cowardly embellishment ends as a commitment to their own misery. and a mirror to the film industry's as well.

8.

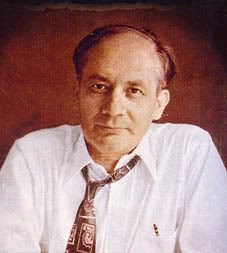

my uncle, james geary, has put another book out. it's his second book concerning the subject of aphorisms (i mentioned the first around here about a year back).

this one is an anthology, rather than a history, like the first. it's remarkably comprehensive, and a lot of fun to flip through. it's also fun to pick the author's brain, as i had the good fortune of doing this week when he was in town for a lecture/book signing. since you can't meet my relatives through the internet (yet?), the next best thing would be to check out this interview with him from NPR's all things considered, conducted on october 2nd.

7.

speaking of people i know, suddenly a lot of my friends are starting blogs. first, a bunch of old friends from undergrad started a silly keep-in-touch type blog called the willow house, named after a now-condemned rowhome that an awful lot of us lived in when we were at the tyler school of art. i've mentioned it before. if you want to kill a few hours watching silly youtube clips, it's a good place to start.

from the comment threads there, i ended up getting back in touch with my old friend rubens ghenov, who's a much more dedicated blogger than i am. he posts about a variety of topics-- art, music, film, fatherhood-- and the enthusiasm i know him to maintain in real life comes through in his writing. he also maintains an art-related blog, with some great black and white drawings. i'm gonna go ahead and post one here...

rubens ghenov: An unpruned vine, the lonelier monk, Sumi ink, charcoal and graphite on paper (18x24)

...from there, my friend aaron-- arguably the last person i'd have guessed would enter the blogosphere-- decided to join in on the fun. his posts jump back and forth between art-related stuff-- paintings, source material, etc.-- and peculiar monologues pertaining to his own childhood. he's been makin' some nice art too:

aaron wexler: Bright Ideas, 2007

6.

i'm moving at the end of the month. my roommate/oldest friend actually bought a place about four blocks away. so i'm going to be his tenant as well as his roommate. for the past week and a half i've been doing some extensive house painting prior to the move, and it's looking pretty good, i must say.

so-- with that and a series of other odds and ends-- the unemployed life has turned out to be pretty lively. initially this was not the case. when the checks started rolling in, and the ease of my first real break from a 40 hour work week in 5 years became a reality, things got a little sluggish. the novelty slowly eroded. by about week three i began to realize that you can only check your email and watch youtube for a finite number of hours before you begin feeling like this:

for better or worse, as i slid ever further into unbridled slackerdom, i was also making my way through samantha power's powerful historical polemic, a problem from hell: america and the age of genocide. i'm not about to embark upon a full-on review here... as a read, it's pretty essential if you're interested in the dark side of 20th century history-- particularly as it relates to u.s. policy. as an argument for intervention, it's nearly impossible to disagree with (given the thoroughness of her research and the ghastliness of the issues at hand)... and also (occasionally) troublesome to agree with entirely (on account of the murkiness and ulterior motivations that inevitably interfere with foreign policy, particularly when it's got a "humanitarian" ring to it).

if anyone has read the book, i'm dying to chat with people about it. i think i'm bumming out my real-life friends by bringing it up incessantly, to be honest...

but what i really wanted to talk about is how it introduced me to the work of raphael lemkin. power brilliantly recounts lemkin's life-long obsession with the notion of atrocity, and how it lead him to coin the term "genocide" as we now know it. my biographical understanding of lemkin is in many ways also a biography of that word-- he devoted the majority of his life to it.

lemkin recognized the power of language, and the deep need for its reconfiguration in the face of world history. the twentieth century was one of unprecedented brutality, and lemkin wanted new words to properly diagnose its wrongdoings. and so he gave us "genocide"-- a tool to address the particular attempts to punish, eliminate, harm or exterminate a group of people along ethnic, racial, cultural or spiritual lines. genocide was to be a barrier toward-- or a replacement of-- the various euphemisms state powers invent to sugarcoat their own malevolence. it was to ensure that grand atrocities would no longer hide beneath the rhetoric of "mass deportations," "excessive force" or "collateral damage." lemkin and his invented word lead the u.n. to assemble the convention on the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide in 1948, which began a long list of arguments, cop-outs, and diplomatic concessions concerning the word (as well as some recent enforcement in international law). hell, it's still going on today in the debates surrounding the armenian genocide in turkey, and the political incentives/ramifications in the west surrounding the use of lemkin's term itself.

what struck me very deeply as i read about lemkin was the intense urgency of his project. i thought, "here is a guy who could *quite literally* wake up in the morning and make a convincing argument that he's doing the most important work in the entire world." this thought (having occurred inside my own, deadbeat brain) was immediately followed by something like: "it's three pm, and it's high time i put a pair of pants on."

i'm not trying to imply that i ought to be saving the world instead of sleeping in (though i could stand to shoot a few more cover letters off). but learning about lemkin did somehow re-shape my understanding of labor. one of the reasons i haven't shuffled off into a mediocre, bill-payin' day job (other than because my unemployment hasn't run out), is that i'm trying to seriously consider the eight hours a day i devote to a paycheck. i'd like to make that time meaningful, and i'm hoping for the best...

here's a picture of me and my mother out saving the universe.

5.

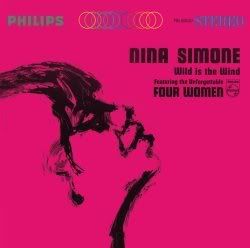

you know, i've been listening to nina simone for well-over a decade now, but until recently i had never necessarily delved into her studio albums. i own a few compilation cd's-- and i love them, of course-- but i've always thought of her in terms of singles, rather than arranged song collections, i guess.

that changed drastically when i recently picked up wild is the wind, from 1966. it's the kind of album that really evolves from track to track, gliding through a wide range of feelings and emotions. it has the kind of build-in anticipation that i love so much-- i don't just revel in the songs themselves, but also the transitions from one track to the next. awaiting those transitions is an integral part of my pleasure. a lot of my very favorite albums expand and contract in this kind of way. i guess i'm a sucker for records that feel like hour-long statements.

i'll share my favorite track from the album, which is also a good candidate for my favorite song ever, for the time being at least:

nina simone, "lilac wine" mp3

4.

i had a grand old time visiting new york city about a month back, and i finally got my butt up to the cloisters collection of the metropolitan museum of art. better still, my new-favorite-real-life-person orchid_and_wasp came along-- and her enthusiasm for 15th century european tapestries *actually managed to mirror my own.* the works themselves didn't disappoint either. the odd display of woven flower patterns and noble unicorns provided exactly the dosage of congested, decorative space i need to slip into my own paintings (in a fucked up sort of way).

even if you're not sold on the idea of a museum full of tapestries and medieval artifacts, the building itself is well worth the hike uptown. perched atop the hudson river, it one-ups central park for providing the illusion that you are no longer in a city at all. it's the perfect little oasis from the overkill of an urban setting, and it's one of my new favorite places in the universe.

3.

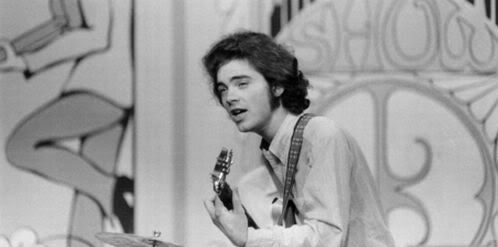

keven mc alester's 2005 film you're gonna miss me: a film about roky erickson is the rarest of a rare breed-- it's a rock and roll documentary with a genuine sense of artistry. no fawning, nostalgic idol worship. no overindulging in cool concert footage as an alternative to having something to say. no meandering, diagnostic discussions with aging rock critics. it's a film with a story to tell-- and mc alester's penetrating approach to it maintains an eccentric sense of wonder akin to werner herzog at his best.

mc alester gets the 13th floor elevators footage out of the way quickly. you're gonna miss me is more concerned with the present than the past. and who knew erikson's present was so goddamned bizarre, anyway? after years of extensive drug abuse, eroding psychological stability and a deeply damaging history with mental health facilities, erikson finds himself at the (sometimes benevolent) mercy of his mother evelyn-- an eccentric, occasionally brilliant pack-rat, whose mystical breed of homespun christianity keeps roky from conventional medicine. his cooped-up life with her eventually leads to an all-out legal custody battle with roky's youngest brother sumner-- a classical tuba player... with a penchant for new age spirituality... who lives in a home that appears as if someone opened an ikea inside of pee wee's playhouse.

all of which must seem like somewhat of a carnival, until you consider the lack of judgment coming from mc alester's lens. unlike the similarly-themed the devil and daniel johnston, his approach is never diagnostic, and the sense of tragedy is more conflicted and peculiar. as i watched the film, i found ample reasons to resent evelyn as well as sumner (to say nothing of roky himself, who hasn't proven much of a father, to say the least). but i also came away with a sense that his family cares deeply about him. the really remarkable thing about the documentary is how it conveys the intimacy of its family dynamic, without sentimentalizing their considerable peculiarities. mc alester wisely avoids positing a standard of normalcy with which to branch out of. i found myself coming to terms with the eriksons as they conceive of themselves. my own preconceptions don't fit into the picture. and within those parameters, there is a genuine feeling of hope to the film as well. it concludes with roky's return to playing music, and watching him pick up the guitar is really remarkable when it happens.

here's the trailer:

2.

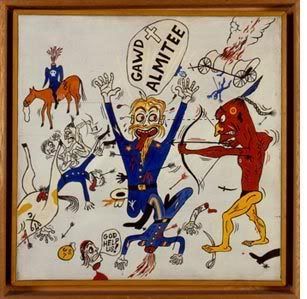

i've always admired h.c. westermann's artwork, but my knowledge of it was pretty sporadic and superficial. thankfully-- due to a random museum trip when my old friend studiojorge was in town over the summer-- i got a more comprehensive look at the guy, thanks to a show of his early work at the pennsylvania academy of the fine arts.

westermann has always struck me as a more light-hearted, typically "american" alternative to joseph cornell. both work with a wide variety of odd materials, creating strangely personal artifacts with few limitations regarding materials. at first glance, westermann's ambitions seem less lofty than cornell's. he's rummaging through a highway trading post while cornell is gazing at the stars. looking at the two in proximity is like differentiating between a comic book (westermann) and a story book (cornell), i guess.

however-- being that i had the good fortune to see a number of westermann pieces in context-- i'm inclined to put less emphasis on the whimsical side of what he does (as well as his parallels to cornell in general). the exhibit certainly deals as much with war and cultural violence as it does with the oddities of americana. or better yet, it occupies the intersection of the two-- unwilling to sacrificing the pathos of the former or the pleasures of the latter.

1.

if you've made it this far you're crazy! get some fresh air!, you're probably getting sick of clicking on hyperlinks and listening to my ramblings. but if you get a chance, i highly recommend looking up this interview with donald b. kraybill, co-author of amish grace: how forgiveness transcended tragedy, from my local NPR affiliate's radio times. if you go to the radio times webpage, use the archive search at the bottom of the screen to find the program for october 1, 2007. it's the interview occupying the second hour of the show.

(apparently there's no easy way to hyperlink to this. apologies. if you search "amish" in their search engine, that should work too.)

the interview concerns the one-year anniversary of a tragic school shooting that occurred in a one-room amish schoolhouse in nickel mines, PA on 10.2.06. the gunman took the lives of five young girls between the ages of 7-13, injured several more, and finally turned the gun on himself. when the story broke locally, i honestly wanted some distance from the outrage. the situation was awful and tragic, but it had all the ingredients for a media circus as well. the potential for scandal struck me as inappropriate, and the breed of pity that inevitably circulated toward the amish seemed mixed up with patronizing, ill-informed assumptions about their culture (as a remaining breed of "noble savages", etc.). suffice to say, i tried to avoid the public reaction as much as possible.

i haven't read kraybill's book. and despite growing up about an hour east of lancaster county, my knowledge of amish culture comes primarily from sources about as diverse as harrison ford and weird al yankovic. but ignorant as i may be, i was still pretty impressed with kraybill's account of the amish reaction to the shootings. several members of the community-- including family members of the slain children-- reached out directly to the family of the killer. a considerable number of amish even attended his funeral. and perhaps most surprisingly (breaking with stereotypes of seclusion and isolation), kraybill describes extensive co-operation with social workers and police officers in the wake of the massacre.

throughout the interview, he tries to characterize a specifically "amish" notion of forgiveness. obviously, i was struck by its sharp contrast to the often draconian, punitive measures taken within my own culture. it's easy to idealize the amish lack of judgment, but there is also a part of me that wonders if their extreme gentility and pacifism isn't also repressive-- perhaps even disingenuous? but ultimately-- for me, at least-- that was the wrong way of approaching the question. at one point, kraybill quotes a local woman who replaces my own vigilante inclinations with the following-- "i hate the evil inside him."

what really got me thinking wasn't whether or not such extreme measures of forgiveness should be taken, so much as the realization that they could be at all. to hate an evil instead of an individual, i'd imagine one must break somewhat with subjectivity itself. individual intentions come down from their pedestal; the force of an action becomes as worthy of investigation as its motivations themselves. i began thinking about the limitations of my own cult of individuality, and how it can lock the world around me in a maze of incrimination and punishment. but within each of my own isolated singularities (my "self", my "beliefs", my "homies") there is undoubtedly infinite pluralities as well. i believe, like walt whitman, that i do "contain multitudes"-- so it's interesting to consider i might also contain them at my worst. anyway... it's useful to be reminded that the world is expansive once in a while, isn't it? and in this case, even gentle, in a certain way. this is what was going on in my head as the interview concluded.

10.

richard hughes' novel a high wind in jamaica engenders the exact breed of surrealism i like best... its setting (initially a jamaican plantation destroyed by a hurricane, later a pirate ship!) is bizarre but also plausible, and its uncanniness owes more to thought out, atmospheric descriptions than to sudden disruptions in logic. in fact it's the logic itself that supplies its weirdness-- the way it naturalizes unlikely situations. its spookiness sets in as one page leads casually to the next. were it not for its occasional-- and totally inexcusable-- bursts of racism, i'd even say it rivals my other favorite classic-of-understated-surrealism: bruno schulz' the street of crocodiles.

like the henry darger painting that graces its cover, jamaica is largely a book about child sexuality. but unlike darger's constipated blend of innocence and repression (brilliant as it may be), hughes' handling of the subject is lucid and respectful. contrary to what i may have looked like in 1993, i've never been a pre-pubescent girl, personally. and i'd wager that hughes hasn't either. but as far as i can tell, he paints a convincing, comprehensive portrait of how that might feel, hormonally-- minus much of the lechery such question-raising might imply.

hughes isolates the tension between playfulness and learned morality with astounding accuracy. the book's precocious central character (emily) emerges at the tail-end of childhood's most limitless pleasures. she is solipsistic and confident-- almost to the point of megalomania. one of the great surprises of the book is the way that hughes reveres her confidence-- there's something convincingly utopian about her ignorance of gender norms, her willingness to follow her obsessive inclinations, and her ability to make a game out of everything. her "sexual awakening" occurs alongside her instinctual bravery in a variety of ways, most notably in her often dangerous interactions with adult men. hughes foreshadows the barriers, frustrations, and new pleasures that might soon arise for her as a growing person. these real-life dangers are rendered with a deep respect for the curiosity they provoke within her (and even, ickily enough, within the "pirates" aboard the ship). the taboos that arise are handled with an unforgiving investigative integrity, but there's a distant gentleness to hughes' writing as well. i found myself able to find parallels between emily's adventures and my own childhood-- particularly those weird, pre-"gendered" moments that society at large would rather not discuss. and it reminded me of the strange balance of confidence, insecurity, sexuality and socialization that determined my own creative abilities, for better or worse.

9.

my growing obsession with apocalyptic imagery lead me to go on a little kick with only-man-left-on-earth movies. it's a fun genre, but i didn't expect to stumble upon any really great films, quite honestly...

i rented ranald mac dougall's 1959 film the world, the flesh and the devil expecting little more than to enjoy the novelty of its premise: the human race has inexplicably vanished overnight, and the last living human is portrayed by harry belafonte.

as silly as this may sound, it's a remarkably sophisticated film in a number of ways-- and one that i think has taken on new meaning with age (as i will get to in a minute). first and foremost, there's the fact that it was made in 1959. the only major entry into the genre at that time was stanley kramer's dull, self-important cold war dystopia on the beach... and even that was released (more or less) concurrently. so-- to the best of my knowledge-- we have the world (and the twilight zone, which also began airing in '59) to thank for our first taste of the eerie, abandoned crane shots, schematic storylines and bitter cultural allegories that would define the genre from night of the living dead on up through 28 days later. hell, it was almost literally remade in 1985 as geoff murphy's the quiet earth, right down to its handling of miscegenation as a central topic.

... which brings us to the strange fate of the film itself. from the tiny bit of cyber-sleuthing i've done regarding the film, i've gathered that belafonte distanced himself from the project upon its release. he thought the film did little justice to the interracial romance that comes to occupy the center of its story, as his character comes to find that there is also a white woman (and later, a white man) who has survived the tragedy. and its true-- it totally chickens out when it comes to depicting their relationship physically.

but the nice thing about art-making is that mistakes can turn out to be assets. in 1959, there was undoubtedly a need to transgress the taboo of race-mixing on screen. the mere act of depiction could be sharply confrontational and politically useful. in 2007, explicit depictions often deaden my viewing experience. taboos and transgressions are par-for-the-course, and uninspired filmmakers litter the screen with them as a substitute for an active, engaged experience. there is a scene about halfway through the world where sarah (inger stevens) asks ralph (belafonte) to give her a haircut. this seemingly banal event points allegorically to all the simmering sexuality mac dougall doesn't quite have the guts to depict. upon its release it was undoubtedly a cop-out; in 2007, it's not only heartbreaking, but sexy as hell. as the mood moves from confrontational to confusing, from bawdy to malevolent-- its hayes code inheritance becomes the issue at hand. my initial titillation deepens considerably, becoming inseparable from its more general sense of melancholy. society might have broken down completely, but somehow its ideology survived. the miscegenation taboo almost zombifies the characters. it looms over their actions, and they become entranced by it. sarah and ralph wander their scorched earth like birds that can't quite hop out of their cages. what begins as a flirtatious and cowardly embellishment ends as a commitment to their own misery. and a mirror to the film industry's as well.

8.

my uncle, james geary, has put another book out. it's his second book concerning the subject of aphorisms (i mentioned the first around here about a year back).

this one is an anthology, rather than a history, like the first. it's remarkably comprehensive, and a lot of fun to flip through. it's also fun to pick the author's brain, as i had the good fortune of doing this week when he was in town for a lecture/book signing. since you can't meet my relatives through the internet (yet?), the next best thing would be to check out this interview with him from NPR's all things considered, conducted on october 2nd.

7.

speaking of people i know, suddenly a lot of my friends are starting blogs. first, a bunch of old friends from undergrad started a silly keep-in-touch type blog called the willow house, named after a now-condemned rowhome that an awful lot of us lived in when we were at the tyler school of art. i've mentioned it before. if you want to kill a few hours watching silly youtube clips, it's a good place to start.

from the comment threads there, i ended up getting back in touch with my old friend rubens ghenov, who's a much more dedicated blogger than i am. he posts about a variety of topics-- art, music, film, fatherhood-- and the enthusiasm i know him to maintain in real life comes through in his writing. he also maintains an art-related blog, with some great black and white drawings. i'm gonna go ahead and post one here...

rubens ghenov: An unpruned vine, the lonelier monk, Sumi ink, charcoal and graphite on paper (18x24)

...from there, my friend aaron-- arguably the last person i'd have guessed would enter the blogosphere-- decided to join in on the fun. his posts jump back and forth between art-related stuff-- paintings, source material, etc.-- and peculiar monologues pertaining to his own childhood. he's been makin' some nice art too:

aaron wexler: Bright Ideas, 2007

6.

i'm moving at the end of the month. my roommate/oldest friend actually bought a place about four blocks away. so i'm going to be his tenant as well as his roommate. for the past week and a half i've been doing some extensive house painting prior to the move, and it's looking pretty good, i must say.

so-- with that and a series of other odds and ends-- the unemployed life has turned out to be pretty lively. initially this was not the case. when the checks started rolling in, and the ease of my first real break from a 40 hour work week in 5 years became a reality, things got a little sluggish. the novelty slowly eroded. by about week three i began to realize that you can only check your email and watch youtube for a finite number of hours before you begin feeling like this:

for better or worse, as i slid ever further into unbridled slackerdom, i was also making my way through samantha power's powerful historical polemic, a problem from hell: america and the age of genocide. i'm not about to embark upon a full-on review here... as a read, it's pretty essential if you're interested in the dark side of 20th century history-- particularly as it relates to u.s. policy. as an argument for intervention, it's nearly impossible to disagree with (given the thoroughness of her research and the ghastliness of the issues at hand)... and also (occasionally) troublesome to agree with entirely (on account of the murkiness and ulterior motivations that inevitably interfere with foreign policy, particularly when it's got a "humanitarian" ring to it).

if anyone has read the book, i'm dying to chat with people about it. i think i'm bumming out my real-life friends by bringing it up incessantly, to be honest...

but what i really wanted to talk about is how it introduced me to the work of raphael lemkin. power brilliantly recounts lemkin's life-long obsession with the notion of atrocity, and how it lead him to coin the term "genocide" as we now know it. my biographical understanding of lemkin is in many ways also a biography of that word-- he devoted the majority of his life to it.

lemkin recognized the power of language, and the deep need for its reconfiguration in the face of world history. the twentieth century was one of unprecedented brutality, and lemkin wanted new words to properly diagnose its wrongdoings. and so he gave us "genocide"-- a tool to address the particular attempts to punish, eliminate, harm or exterminate a group of people along ethnic, racial, cultural or spiritual lines. genocide was to be a barrier toward-- or a replacement of-- the various euphemisms state powers invent to sugarcoat their own malevolence. it was to ensure that grand atrocities would no longer hide beneath the rhetoric of "mass deportations," "excessive force" or "collateral damage." lemkin and his invented word lead the u.n. to assemble the convention on the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide in 1948, which began a long list of arguments, cop-outs, and diplomatic concessions concerning the word (as well as some recent enforcement in international law). hell, it's still going on today in the debates surrounding the armenian genocide in turkey, and the political incentives/ramifications in the west surrounding the use of lemkin's term itself.

what struck me very deeply as i read about lemkin was the intense urgency of his project. i thought, "here is a guy who could *quite literally* wake up in the morning and make a convincing argument that he's doing the most important work in the entire world." this thought (having occurred inside my own, deadbeat brain) was immediately followed by something like: "it's three pm, and it's high time i put a pair of pants on."

i'm not trying to imply that i ought to be saving the world instead of sleeping in (though i could stand to shoot a few more cover letters off). but learning about lemkin did somehow re-shape my understanding of labor. one of the reasons i haven't shuffled off into a mediocre, bill-payin' day job (other than because my unemployment hasn't run out), is that i'm trying to seriously consider the eight hours a day i devote to a paycheck. i'd like to make that time meaningful, and i'm hoping for the best...

here's a picture of me and my mother out saving the universe.

5.

you know, i've been listening to nina simone for well-over a decade now, but until recently i had never necessarily delved into her studio albums. i own a few compilation cd's-- and i love them, of course-- but i've always thought of her in terms of singles, rather than arranged song collections, i guess.

that changed drastically when i recently picked up wild is the wind, from 1966. it's the kind of album that really evolves from track to track, gliding through a wide range of feelings and emotions. it has the kind of build-in anticipation that i love so much-- i don't just revel in the songs themselves, but also the transitions from one track to the next. awaiting those transitions is an integral part of my pleasure. a lot of my very favorite albums expand and contract in this kind of way. i guess i'm a sucker for records that feel like hour-long statements.

i'll share my favorite track from the album, which is also a good candidate for my favorite song ever, for the time being at least:

nina simone, "lilac wine" mp3

4.

i had a grand old time visiting new york city about a month back, and i finally got my butt up to the cloisters collection of the metropolitan museum of art. better still, my new-favorite-real-life-person orchid_and_wasp came along-- and her enthusiasm for 15th century european tapestries *actually managed to mirror my own.* the works themselves didn't disappoint either. the odd display of woven flower patterns and noble unicorns provided exactly the dosage of congested, decorative space i need to slip into my own paintings (in a fucked up sort of way).

even if you're not sold on the idea of a museum full of tapestries and medieval artifacts, the building itself is well worth the hike uptown. perched atop the hudson river, it one-ups central park for providing the illusion that you are no longer in a city at all. it's the perfect little oasis from the overkill of an urban setting, and it's one of my new favorite places in the universe.

3.

keven mc alester's 2005 film you're gonna miss me: a film about roky erickson is the rarest of a rare breed-- it's a rock and roll documentary with a genuine sense of artistry. no fawning, nostalgic idol worship. no overindulging in cool concert footage as an alternative to having something to say. no meandering, diagnostic discussions with aging rock critics. it's a film with a story to tell-- and mc alester's penetrating approach to it maintains an eccentric sense of wonder akin to werner herzog at his best.

mc alester gets the 13th floor elevators footage out of the way quickly. you're gonna miss me is more concerned with the present than the past. and who knew erikson's present was so goddamned bizarre, anyway? after years of extensive drug abuse, eroding psychological stability and a deeply damaging history with mental health facilities, erikson finds himself at the (sometimes benevolent) mercy of his mother evelyn-- an eccentric, occasionally brilliant pack-rat, whose mystical breed of homespun christianity keeps roky from conventional medicine. his cooped-up life with her eventually leads to an all-out legal custody battle with roky's youngest brother sumner-- a classical tuba player... with a penchant for new age spirituality... who lives in a home that appears as if someone opened an ikea inside of pee wee's playhouse.

all of which must seem like somewhat of a carnival, until you consider the lack of judgment coming from mc alester's lens. unlike the similarly-themed the devil and daniel johnston, his approach is never diagnostic, and the sense of tragedy is more conflicted and peculiar. as i watched the film, i found ample reasons to resent evelyn as well as sumner (to say nothing of roky himself, who hasn't proven much of a father, to say the least). but i also came away with a sense that his family cares deeply about him. the really remarkable thing about the documentary is how it conveys the intimacy of its family dynamic, without sentimentalizing their considerable peculiarities. mc alester wisely avoids positing a standard of normalcy with which to branch out of. i found myself coming to terms with the eriksons as they conceive of themselves. my own preconceptions don't fit into the picture. and within those parameters, there is a genuine feeling of hope to the film as well. it concludes with roky's return to playing music, and watching him pick up the guitar is really remarkable when it happens.

here's the trailer:

2.

i've always admired h.c. westermann's artwork, but my knowledge of it was pretty sporadic and superficial. thankfully-- due to a random museum trip when my old friend studiojorge was in town over the summer-- i got a more comprehensive look at the guy, thanks to a show of his early work at the pennsylvania academy of the fine arts.

westermann has always struck me as a more light-hearted, typically "american" alternative to joseph cornell. both work with a wide variety of odd materials, creating strangely personal artifacts with few limitations regarding materials. at first glance, westermann's ambitions seem less lofty than cornell's. he's rummaging through a highway trading post while cornell is gazing at the stars. looking at the two in proximity is like differentiating between a comic book (westermann) and a story book (cornell), i guess.

however-- being that i had the good fortune to see a number of westermann pieces in context-- i'm inclined to put less emphasis on the whimsical side of what he does (as well as his parallels to cornell in general). the exhibit certainly deals as much with war and cultural violence as it does with the oddities of americana. or better yet, it occupies the intersection of the two-- unwilling to sacrificing the pathos of the former or the pleasures of the latter.

1.

if you've made it this far you're crazy! get some fresh air!, you're probably getting sick of clicking on hyperlinks and listening to my ramblings. but if you get a chance, i highly recommend looking up this interview with donald b. kraybill, co-author of amish grace: how forgiveness transcended tragedy, from my local NPR affiliate's radio times. if you go to the radio times webpage, use the archive search at the bottom of the screen to find the program for october 1, 2007. it's the interview occupying the second hour of the show.

(apparently there's no easy way to hyperlink to this. apologies. if you search "amish" in their search engine, that should work too.)

the interview concerns the one-year anniversary of a tragic school shooting that occurred in a one-room amish schoolhouse in nickel mines, PA on 10.2.06. the gunman took the lives of five young girls between the ages of 7-13, injured several more, and finally turned the gun on himself. when the story broke locally, i honestly wanted some distance from the outrage. the situation was awful and tragic, but it had all the ingredients for a media circus as well. the potential for scandal struck me as inappropriate, and the breed of pity that inevitably circulated toward the amish seemed mixed up with patronizing, ill-informed assumptions about their culture (as a remaining breed of "noble savages", etc.). suffice to say, i tried to avoid the public reaction as much as possible.

i haven't read kraybill's book. and despite growing up about an hour east of lancaster county, my knowledge of amish culture comes primarily from sources about as diverse as harrison ford and weird al yankovic. but ignorant as i may be, i was still pretty impressed with kraybill's account of the amish reaction to the shootings. several members of the community-- including family members of the slain children-- reached out directly to the family of the killer. a considerable number of amish even attended his funeral. and perhaps most surprisingly (breaking with stereotypes of seclusion and isolation), kraybill describes extensive co-operation with social workers and police officers in the wake of the massacre.

throughout the interview, he tries to characterize a specifically "amish" notion of forgiveness. obviously, i was struck by its sharp contrast to the often draconian, punitive measures taken within my own culture. it's easy to idealize the amish lack of judgment, but there is also a part of me that wonders if their extreme gentility and pacifism isn't also repressive-- perhaps even disingenuous? but ultimately-- for me, at least-- that was the wrong way of approaching the question. at one point, kraybill quotes a local woman who replaces my own vigilante inclinations with the following-- "i hate the evil inside him."

what really got me thinking wasn't whether or not such extreme measures of forgiveness should be taken, so much as the realization that they could be at all. to hate an evil instead of an individual, i'd imagine one must break somewhat with subjectivity itself. individual intentions come down from their pedestal; the force of an action becomes as worthy of investigation as its motivations themselves. i began thinking about the limitations of my own cult of individuality, and how it can lock the world around me in a maze of incrimination and punishment. but within each of my own isolated singularities (my "self", my "beliefs", my "homies") there is undoubtedly infinite pluralities as well. i believe, like walt whitman, that i do "contain multitudes"-- so it's interesting to consider i might also contain them at my worst. anyway... it's useful to be reminded that the world is expansive once in a while, isn't it? and in this case, even gentle, in a certain way. this is what was going on in my head as the interview concluded.