Art, Up Close

I had promised earlier this week to write about our trip to the Brandywine River Museum to see the special Edward Gorey exhibit. We went with my Dad this past Sunday, and we all enjoyed it very much. In addition, we got to see paintings by illustrator N.C. Wyeth and his famous son, Andrew Wyeth, as well as various other works.

View from the Brandywine River Museum

The reason that we went to the museum was somewhat fortuitous. The events and attractions guide used by most of the Philadelphia tourist sites was down Sunday morning, which made it difficult to plan.

But then I remembered that many of my Philadelphia friends had been talking about the Edward Gorey exhibit, so we went directly to the museum's site and found out the information. When we called Dad, he was interested and knew where the museum was, so we agreed to just meet there, rather than driving all the way to his hotel in Valley Forge.

The day was gray and rainy, and normally this would not affect a museum visit. This particular museum also has a lot of gardens and grounds, since it's located a stone's throw from the N.C. Wyeth residence and in the same area that inspired all of Andrew's paintings. The museum houses works by the Wyeth family, as well as many works of art from illustrators, portrait artists and still life painters, all of which relate to the Wyeth family's interests in painting.

Edward Gorey, of course, is a 20th century artist and illustrator whose darkly humorous black and white drawings are easily recognizable. Many people know them from the opening animation sequence of Mystery on PBS. He also illustrated a well-known edition of T.S. Elliot's Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats.

I had always loved Edward Gorey's work, especially his dark takes on nursery rhymes.

We started, of course, with the Gorey exhibit. There was, of course, no photography allowed. The exhibition represented a sampler of his work from throughout his life, including illustrations from his books and even miscellaneous items, such as sketches, or envelopes he'd decorated for letters to his mother in college.

The most fascinating aspect of seeing Gorey's work in person was noticing how truly detailed they are. Looking at them, you can see the care that he took to do them properly. I was also interested to see the places where he made a mistake: where something was whited out, or where he'd pasted a word or a portion of a drawing over something that he didn't liked.

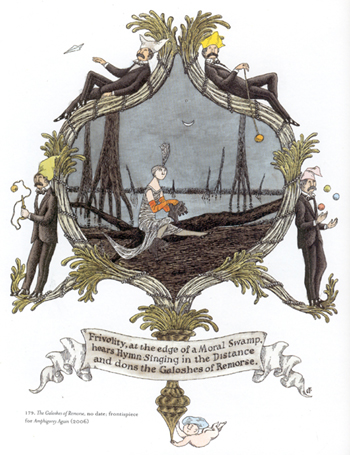

Much of this material I hadn't seen before, and it made me laugh out loud. Other people were having similar reactions all over the museum. One of my favorites was the frontispiece for his second collected works, Amphigorey Too. It features a woman in an evening dress, with an elaborate head piece, sitting next to a dark swamp, holding a pair of galoshes. On the edges of the design, standing or lying on a vine-like border, are four men engaged in frivolous pursuits: flying a paper airplane, playing with a yo-yo, playing with a ball-and-cup game, and juggling. Underneath them, a banner reads, "Frivolity, at the edge of a Moral Swamp, hears Hymn Singing in the Distance and dons the Galoshes of Despair."

I encourage you to click on this photo and view it at a larger size so that you can see the detail.

I can't tell you exactly why that piece made me laugh so hard, except that it's a perfect example of an intentionally heavy-handed metaphor. A lot of his humor is like that: you laugh because there's something wrong about it.

The exhibit also included a stuffed version of one of his creatures, which was sort of a black, blobby humanoid with extra long arms. I found myself wondering if he intended to give it to a child, and what sort of reaction a child would have to such an odd toy.

You could get a sense for Gorey's sense of humor. I found myself wondering how he could be at the same time so precise and so given to fancy. Then again, I think it's people with the most ordered minds who find nonsense so appealing.

One somewhat Gorean moment of the exhibit were these two older women who didn't get most of the jokes. They would examine every drawing very carefully, reading it out loud (a difficult feat, since many of his drawings included French and nonsense words), sounding it out painfully, syllable by syllable. Instead of grasping the joke within a few seconds, like most of the guests, they seemed utterly baffled, and they would engage in protracted discussions over why the drawing was supposed to be funny. They never laughed, really, but they were very earnest about trying to understand the jokes.

I was behind them for a while, but then I moved along, because it was getting on my nerves. Near the end of the exhibit, I was near them again, viewing some costume designs Gorey had done near the end of his life for a production of Mikado. As they leaned in close to view the last couple of drawings, one of them pronounced, "Well, they're very hangable." The other agreed.

I laughed out loud, imagining them hanging one of Gorey's illustrations in their home, never understanding the joke behind it. I also thought immediately of what Gorey's artistic response would be to his work being declared "hangable." I imagine it would be a self-portrait in his famous beaver coat, hanging from a gallows while two old ladies held up a frame in front of him.

Then we visited the rest of the museum, starting with the N.C. Wyeth gallery, which included his original illustrations for such books as Treasure Island. They were huge oil paintings. I'm not sure how the book illustration process worked back then, but it was clearly different from today's. I understand he would ship them to the publisher, who would copy them using a process that was not explained.

The Brandywine River Museum has put together an excellent online resource of the elder Wyeth's work, which includes details on his paintings, if you'd like to see them for yourself.

Unlike the Gorey exhibit, there was more information available about N.C. Wyeth's biography and career. Although he was primarily known for his illustrations, he always wanted to be known simply as a painter. His work is very dynamic, with a strong contrast lights and darks and clear lines. His colors were vivid, which does not always come through when they're reproduced.

We also got to see some of the weapons that he used as props in his paintings. He collected antique firearms just for that purpose, and they were never used. A rotating display of portions of his collection is part of the gallery.

His most interesting painting that was not an illustration was based on a dream he'd had, and it's called "In a Dream I Meet General Washington" (just type "dream" into the search window at the above-mentioned online resource to see it). He'd been working on a mural of George Washington and had dreamt that Washington came alive and started narrating the battle. The painting shows him on a ladder, while George Washington leans out of the painting and talks to him, with a battle taking place in the background. The original, unlike the reproduction, has luminous colors, with pastel, dreamlike hills.

N.C. Wyeth painted every day, and he did quite a few still lifes (the way that musicians play scales), some of which were on display.

Also on the same floor was a gallery of American painters of portraits and still lifes. Many of them were from the Philadelphia area. We were particularly impressed with the hyper-realistic paintings of George Cope. He was best known for his "trompe l'oeil" paintings, which to translate the French literally, fool the eye. Again, it's hard to tell from the reproductions, but standing in front of the paintings, they looked so real you thought that you could grab the objects. Talk about a painstaking attention to detail!

Another floor featured paintings by Andrew Wyeth (official Web site; Wikipedia article), which are very different from his father's. He did not study formally with him, although he was a frequent visitor to his father's studio as a boy.

Andrew Wyeth is known for his tempura paintings, which uses tinted egg to produce very natural, almost ethereal colors. For his entire life, he set his paintings in the world around him, painting his neighbors and the scenery around him. Unlike a typical landscape artist, he didn't produce paintings of rolling fields and luminous sunsets, or an idealized farmhand loading hay. Instead, he made the ordinary beautiful: whether it was a broken-down pig pen or an elderly woman raking leaves in early-morning light.

Paintings of such supposedly simple subjects can be much more complex than you might realize, and I was interested to see just how much detail was evident in these deceptively simple works. Unlike his father's thick layers of paint, Andrew Wyeth's work seems delicate, ephemeral, almost Impressionistic. His work, compared to his father's, is like a haiku compared to a Shakespearean sonnet.

I enjoyed reading the information posted next to the paintings, since it often included Wyeth's own words about those paintings, taken from interviews or his writings.

On the same floor, as I remember, was a gallery that included other paintings by members of the extended Wyeth family. Of particular interest were those by Andrew's son Jamie, who actually studied with his aunt, Carolyn, a skilled portrait artist. He's particularly interested in the stage and in dance, and painted some well-known portraits of the ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev. There are also some paintings by Peter Hurd, who married Andrew's sister, Henriette.

In a gallery on the ground floor we viewed the exhibit on American illustration. It even had a few Maxfield Parish frontispieces, which were very intricate, although not as instantly recognizable as his larger paintings.

Then, since we had time, we got some lunch in the cafeteria and purchased tickets for the tour of N.C. Wyeth's residence and studio.

By this point, the rain was really coming down, so I wasn't sure whether I would buy the exhibition book on the Gorey exhibit. Turns out it is available through the museum's online catalog, although the person at the register didn't know whether or not it was. As it turned out, though, I did have time after the tour to purchase it.

We bought tickets and rode a little mini bus up to the house, both of which were built by N.C. Wyeth with money earned from the Treasure Island illustrations. Yes, illustrators were paid handsomely in those days! Our fellow passengers were enjoying themselves despite the rain, making small talk and cracking jokes.

Again, pictures were not allowed inside the buildings, but I got some good photos outside. I would have gotten some with The Gryphon and Dad in them, but it seemed a bit cruel to make them stand in the rain.

The N.C. Wyeth residence

The Wyeths' front lawn, from the porch

The house was a simple brick building, never owned by anyone outside the Wyeth family. After N.C. and his wife passed away, daughter Carolyn lived there until her death until 1996. All of the furnishings are original to the family, including a grand piano, some sitting-room couches in the large room where the family would gather, and a special dining-room table designed by NC to fit inside their narrow, wood-paneled dining room.

There are also a few portraits of family members from several generations on the walls. As the tour guide explained, the Wyeth family did not like photographs but preferred paintings.

Despite living in the 20th century he died an accident at a railroad crossing in 1945 N.C. Wyeth did not cotton to modern appliances. The family read books and played the piano for entertainment. Of course, Carolyn might have acquired some more modern items during her long life, but they were not on display.

Then we got back in the bus and rode up to the studio, which N.C. Wyeth had built on the top of the hill to get more light. His studio featured large windows on the north side, which is ideal for letting in the most natural light during the day. Even though it was a gray day, even without any electronic lights, the studio was fairly well-lit inside.

Every day, he'd take his daily "commute": walking the flagstone path up to his studio from the house.

N.C. Wyeth's daily commute to work

N.C. Wyeth's studio

Window of N.C. Wyeth's studio

I have seen photos of other artists' studios, and they always look like such fabulous places to hang out: filled with items of inspiration along with crafts of the trade. N.C. Wyeth had a foyer that included a large box filled with costumes, which the children were allowed to use for games of make-believe. A shelf was filled with bound collections of the magazines that carried his illustrations, while another rack contained prop guns.

The original studio, with its large plate glass window, had an easel, cigar boxes full of paints, and containers of brushes. But it also had neatly organized stacks of National Geographics, Greek busts, a fantastic model ship, rounded green glass bottles, and even a stuffed river otter!

A lower level, built later, was used to paint large murals. He could hang them on a wall and use a specially-built rolling ladder to access whatever portion he was painting. Paintings by N.C. Wyeth were actually on display, as if he'd just finished them.

I can imagine what it must have been like for the Wyeth children, visiting their dad whenever he was at work, playing with the props, smelling the paint, and looking out the window at the green vistas. No wonder so many of them took to art.

As we left, I thought about how Wyeth's studio contrasts with my own office, a cramped room that also serves as a guest room. My best intentions of organization, born in January, have since lain fallow, and it contains stacks of papers and books, threatening to spill over, causing me to infrequently cull them. A collapsible tray table sits next to my desk (itself an ill-designed creation from Fingerhut, with a middle shelf that allows for storage but is inconvenient for anyone with knees). On a nearby shelving unit, boxes from IKEA contain old computer disks, folders, envelopes, and miscellany. The opposite walk hjas two book shelves stacked on top of each other: one containing reference books, poetry books, and books to review for Wild Violet; the other being my "books to read" shelf, which is currently spilling over. A few works of art hang on the wall: a pastel of my dog Una, done by my Mom; a young woman patting a stuffed bunny, which was left behind, with no artist info, at an Otakon art auction; a collage my sister did for me that includes photos of women from all over the world.And of course, against the wall to the left of my desk, sitting on top of a plastic rolling shelf in which I keep office supplies, the small TV where I watch American Idol and other shows. (I'm such a multi-tasker.)

Since my window looks out only on the houses across the alley, I always keep the blinds closed, with just a couple inches of space to let the light in. No wonder I often walk my dog to get inspired!

When we get a bigger place, I'd like to have an office that's more like an art studio, with items of inspiration on display. A view would be nice, too.

Moral:

Seeing a print is nothing like seeing the original.