Book-It 'o12! Book #8

The Fifty Books Challenge, year three! (Years one, two, and three just in case you're curious.) This was a library request.

FULL DISCLOSURE: M.G. Lord has become a friend of mine since I tracked her down on Facebook (hoping she had a personal page I could "fan") and she graciously tolerated my creepy, gushing fangirling of her seminal Forever Barbie (what Spin magazine deemed in its Riot Grrl issue essential Third Wave reading) which I voraciously consumed at fourteen and haven't been the same since.

FULL DISCLOSURE REGARDING FULL DISCLOSURE: I've been really looking forward to disclosing that.

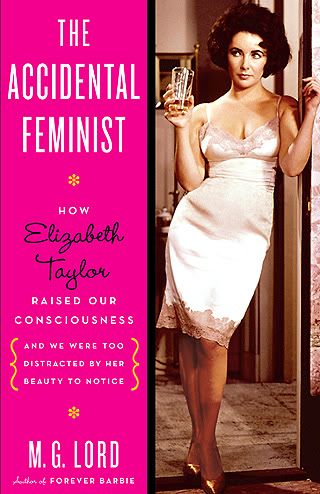

Title: The Accidental Feminist: How Elizabeth Taylor Raised Our Consciousness and We Were Too Distracted by Her Beauty to Notice by M.G. Lord

Details: Copyright 2012, Walker & Company

Synopsis (By Way of Front Flap): "From the brilliant cultural historian M.G. Lord, an intimate examination of the unexpected feminist content in Elizabeth Taylor's iconic roles.

Countless books have chronicled the life of Elizabeth Taylor, but rarely has her career been examined from the point of view of her on-screen persona. That persona, argues M.G. Lord, has repeatedly introduced a broad audience to feminist ideas.

In her breakout film, National Velvet (1944), Taylor's character challenges gender discrimination: Forbidden as a girl to ride her beloved horse in an important race, she poses as a male jockey. Her next milestone, A Place in the Sun (1951), can be seen as an abortion rights movie-a cautionary tale from a time before women had ready access to birth control. In Butterfield 8 (1960), for which she won an Oscar, Taylor isn't censured because she's a prostitute, but because she chooses the men with whom she sleeps-- she controls her sexuality. Even the classic Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) depicts the anguish that befalls a woman when the only way she can express herself is through her husband's career and children. Other of Taylor's performance explore similar themes.

The legendary actress has lived her life defiantly in public-undermining post-war reactionary sex roles; helping directors thwart the Hollywood Production Code, which restricted film content between 1934 and 1967; fundraising for AIDS research in the 1980s; championing the rights of people to love whom they love, regardless of gender. Yet her powerful feminist impact has been hidden in plain sight. Daring in conception and drawing upon unpublished letters and scripts, and on interviews with Kate Burton, Gore Vidal, Austin Pendleton, Kevin McCarthy, Liz Smith, and others, The Accidental Feminist will surprise readers with its originality and will add a startling dimension to the star's enduring mystique."

Why I Wanted to Read It: As mentioned, I've been a fan of Lord's work for a long time now.

How I Liked It: If I weren't familiar with the author, I admit I'd probably largely dismiss this book on sight as postmortem straw-grasping. Taylor wasn't even a dead a year (when this was published) and already the Monroe-esque biographers are coming out to render her image in theirs? Certainly, this is a more admirable task since it's coming from a feminist angle, but really, isn't that part of the problem? Taking something that we like, regardless of its problematic tendencies, and reworking it to "seem" feminist and therefore alleviate some of our guilt, rather than admitting we like something problematic? Isn't that how bunk like "Destiny's Child are feminist icons," gets going?

But fortunately, I could scrap that prejudice and I urge you to do that same. For one, Lord started this book long before Taylor's death (I am too pleased to smugly offer personal evidence of this: on my birthday in June of 2010, I was agog at my friend Sarah's amazing gift of John Waters's new book, autographed to me. When wishing me a happy birthday, M.G added she hoped I'd find her new book at least somewhat as interesting when it came out "next year.") and notes within confirm research from at least as far back as 2008. As she describes, the book came into focus as she began to partake of old favorite films via Netflix and noticed an odd trend in Elizabeth Taylor's films.

This isn't a biography of Elizabeth Taylor. It's a biography of her films and how her life (and legend, and stardom) related to them and vice versa. Lord makes her case soundly and logically, taking us dutifully (but interestingly) through each film for examination. Eschewing further my "I-like-this-so-let's-gloss-over-it" prejudice, Lord evenhandedly eviscerates Taylor's films that not only do not promote an egalitarian message, but actively promote vapidity whether on purpose or more likely, but virtue of being a mere artless studio product (Father of the Bride, Raintree County).

She dissects Taylor's film characters not only on screen but off, noting Taylor's collaborations with the film's creators to push against various industry (and society et large at the time) moral restrictions. I've got a fairly high radar for what I feel to be "intellectual masturbation" (see: glossing over the problematic), and Lord deftly avoids this, citing dialog, scenes, and context: in other words, facts.

Lord doesn't stop at Taylor's films, however. While she nudges through Taylor's tumultuous personal life (mostly in respect to which films were offered to her and received by the public), she devotes a considerable portion (as she should) to Taylor's pioneering AIDS activism. It could be argued that Taylor taking control of her own celebrity for something charitable (and in desperate need of a champion for the cause) is in and of itself an act of empowerment (as was her building of her own enormously successful fragrance empire). Lord links Taylor's fearlessness in her fight against AIDS and the public misconception to the fearlessness she displayed in her better film characters. Of course, they were characters. Fictional. Taylor was playing a role in each fierce woman. But, as Lord evidences, Taylor's efforts behind the scenes suggest that Taylor was an egalitarian and a fighter long before the AIDS epidemic offered her a public persona as something other than just a movie star (albeit a talented one) and tabloid staple.

This book runs appeal to several groups, as most of Lord's work does. Taylor fans will find a new (and thoughtful) consideration of their idol. Feminists (particularly those of the third wave such as myself) are invited to reconsider again "what a feminist look like."

And there is always the hope that this book adds to the jostling that is still necessary of the rigid belief (largely by opponents of feminism) of what a feminist can and cannot be.

Notable:

“Smell-O-Vistion should not be confused with Odorama, the facetious scratch-and-sniff card that director John Waters created for his 1981 movie, Polyester.” (pg 62)

“The film [Boom] has fans (including director John Waters), but it strains credibility.” (pg 135)

Thank you, M.G.

FULL DISCLOSURE: M.G. Lord has become a friend of mine since I tracked her down on Facebook (hoping she had a personal page I could "fan") and she graciously tolerated my creepy, gushing fangirling of her seminal Forever Barbie (what Spin magazine deemed in its Riot Grrl issue essential Third Wave reading) which I voraciously consumed at fourteen and haven't been the same since.

FULL DISCLOSURE REGARDING FULL DISCLOSURE: I've been really looking forward to disclosing that.

Title: The Accidental Feminist: How Elizabeth Taylor Raised Our Consciousness and We Were Too Distracted by Her Beauty to Notice by M.G. Lord

Details: Copyright 2012, Walker & Company

Synopsis (By Way of Front Flap): "From the brilliant cultural historian M.G. Lord, an intimate examination of the unexpected feminist content in Elizabeth Taylor's iconic roles.

Countless books have chronicled the life of Elizabeth Taylor, but rarely has her career been examined from the point of view of her on-screen persona. That persona, argues M.G. Lord, has repeatedly introduced a broad audience to feminist ideas.

In her breakout film, National Velvet (1944), Taylor's character challenges gender discrimination: Forbidden as a girl to ride her beloved horse in an important race, she poses as a male jockey. Her next milestone, A Place in the Sun (1951), can be seen as an abortion rights movie-a cautionary tale from a time before women had ready access to birth control. In Butterfield 8 (1960), for which she won an Oscar, Taylor isn't censured because she's a prostitute, but because she chooses the men with whom she sleeps-- she controls her sexuality. Even the classic Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) depicts the anguish that befalls a woman when the only way she can express herself is through her husband's career and children. Other of Taylor's performance explore similar themes.

The legendary actress has lived her life defiantly in public-undermining post-war reactionary sex roles; helping directors thwart the Hollywood Production Code, which restricted film content between 1934 and 1967; fundraising for AIDS research in the 1980s; championing the rights of people to love whom they love, regardless of gender. Yet her powerful feminist impact has been hidden in plain sight. Daring in conception and drawing upon unpublished letters and scripts, and on interviews with Kate Burton, Gore Vidal, Austin Pendleton, Kevin McCarthy, Liz Smith, and others, The Accidental Feminist will surprise readers with its originality and will add a startling dimension to the star's enduring mystique."

Why I Wanted to Read It: As mentioned, I've been a fan of Lord's work for a long time now.

How I Liked It: If I weren't familiar with the author, I admit I'd probably largely dismiss this book on sight as postmortem straw-grasping. Taylor wasn't even a dead a year (when this was published) and already the Monroe-esque biographers are coming out to render her image in theirs? Certainly, this is a more admirable task since it's coming from a feminist angle, but really, isn't that part of the problem? Taking something that we like, regardless of its problematic tendencies, and reworking it to "seem" feminist and therefore alleviate some of our guilt, rather than admitting we like something problematic? Isn't that how bunk like "Destiny's Child are feminist icons," gets going?

But fortunately, I could scrap that prejudice and I urge you to do that same. For one, Lord started this book long before Taylor's death (I am too pleased to smugly offer personal evidence of this: on my birthday in June of 2010, I was agog at my friend Sarah's amazing gift of John Waters's new book, autographed to me. When wishing me a happy birthday, M.G added she hoped I'd find her new book at least somewhat as interesting when it came out "next year.") and notes within confirm research from at least as far back as 2008. As she describes, the book came into focus as she began to partake of old favorite films via Netflix and noticed an odd trend in Elizabeth Taylor's films.

This isn't a biography of Elizabeth Taylor. It's a biography of her films and how her life (and legend, and stardom) related to them and vice versa. Lord makes her case soundly and logically, taking us dutifully (but interestingly) through each film for examination. Eschewing further my "I-like-this-so-let's-gloss-over-it" prejudice, Lord evenhandedly eviscerates Taylor's films that not only do not promote an egalitarian message, but actively promote vapidity whether on purpose or more likely, but virtue of being a mere artless studio product (Father of the Bride, Raintree County).

She dissects Taylor's film characters not only on screen but off, noting Taylor's collaborations with the film's creators to push against various industry (and society et large at the time) moral restrictions. I've got a fairly high radar for what I feel to be "intellectual masturbation" (see: glossing over the problematic), and Lord deftly avoids this, citing dialog, scenes, and context: in other words, facts.

Lord doesn't stop at Taylor's films, however. While she nudges through Taylor's tumultuous personal life (mostly in respect to which films were offered to her and received by the public), she devotes a considerable portion (as she should) to Taylor's pioneering AIDS activism. It could be argued that Taylor taking control of her own celebrity for something charitable (and in desperate need of a champion for the cause) is in and of itself an act of empowerment (as was her building of her own enormously successful fragrance empire). Lord links Taylor's fearlessness in her fight against AIDS and the public misconception to the fearlessness she displayed in her better film characters. Of course, they were characters. Fictional. Taylor was playing a role in each fierce woman. But, as Lord evidences, Taylor's efforts behind the scenes suggest that Taylor was an egalitarian and a fighter long before the AIDS epidemic offered her a public persona as something other than just a movie star (albeit a talented one) and tabloid staple.

This book runs appeal to several groups, as most of Lord's work does. Taylor fans will find a new (and thoughtful) consideration of their idol. Feminists (particularly those of the third wave such as myself) are invited to reconsider again "what a feminist look like."

And there is always the hope that this book adds to the jostling that is still necessary of the rigid belief (largely by opponents of feminism) of what a feminist can and cannot be.

Notable:

“Smell-O-Vistion should not be confused with Odorama, the facetious scratch-and-sniff card that director John Waters created for his 1981 movie, Polyester.” (pg 62)

“The film [Boom] has fans (including director John Waters), but it strains credibility.” (pg 135)

Thank you, M.G.