Book-It 'o9! Book #40

More of the Fifty Books Challenge! This was a library request.

Title: A History of Witchcraft: Sorcerers, Heretics, and Pagans SECOND EDITION by Jeffrey B. Russell and Brooks Alexander

Details: Copyright 2007, Thames & Hudson Inc

Synopsis (By Way of Back Cover): "For nearly thirty years, this book has been the authoritative illustrated history of witchcraft. Now, in collaboration with Brooks Alexander, who has himself conducted innovative research in the field, Jeffrey Russell's study has been fully revised with additional chapters accompanied by new illustrations. As history shows, whether or not one believes in witchcraft, one must believe in the existence of witches. Here, the definition of witchcraft in its many diverse forms is discussed and its historical, anthropological and religious manifestations charted from ancient times to the present. Alexander includes an analysis of the importance of the Internet and films in the dissemination of modern witchcraft and the potential tensions as a secretive, initiatory cult becomes and open and recognized religion."

Why I Wanted to Read It: Another find from Atomic Books's catalog and surprisingly a history of Paganism ("to the present") that I haven't read before.

How I Liked It: The book pleased me from the start with a line in Jeffrey B. Russell's section of the preface, wherein he states

"Whether or not one believes in the powers of witchcraft, one must believe in the existence of witches: I have known quite a few personally." (pg 7)

Why does this please me so? It's a nice change from the dismissive tones that suggest somehow we aren't "real" witches in that we don't conform to the Hollywood and storybook standard of witchcraft, that our religion(s) is/are no less real than someone claiming to be a vampire or werewolf.

The book's first section "Sorcery and Historical Witchcraft" is rather dry and at times spotty. It whisks through areas crucial to the movement of modern Paganism (such as the Romanticism of the 19th century) and lingers on the well-mined others, such as the Witchcraze in Europe and the Salem Witch Trials, both eras which have explored in varying depth by dozens of other books.

The book does pick up when it reaches the second section "Modern Witchcraft". In a book of this size, it would be impossible for this book to attempt a Triumph of the Moon level of study, but it does offer a decent overview and what Triumph doesn't, a bit of the history and evolution of various sects of Witchcraft and the "repackaging and rebranding" it's underwent (and continues to undergo) to appeal to various subcultures. The authors declare a pivotal point in the 1996 release of the film The Craft.

"The Craft is different from all previous Hollywood films about witchcraft in one important respect: it presents a picture of modern witchcraft that actually resembles the real thing, instead of being based on the standard medieval stereotypes. That is not an accident, of course, nor is it the result of merely casual research. The film's producers sought out a prominent witch from the occult community in Los Angeles to act as a consultant on the script. Pat Devin, who was then Co-National Public Information Officer for the Covenant of the Goddess (CoG), worked with Sony for two years to bring the film version of modern witchcraft substantially into line with the real-life version. The result is that, although modern Witchcraft was sensationalized for the sake of the film, it is still identifiably modern witchcraft. Despite [Pagan historian Margot]Adler's horrified reaction (she called it 'the worst movie ever made!'), The Craft turned out to be a magnet for modern witchcraft for two reasons. The first is a matter of simple psychology: the lesson of the film's 'cautionary example' (i.e., that lust for control leads to the loss of control) is largely lost on teenagers, but its dangled lure of occult power definitely is not. A sense of attraction to the dream of control (especially the dream of controlling others) is what the film lastingly conveys. The second reason is that the witchcraft in the film resembles the real thing, its lure of occult power is linked to a collection of ideas, rituals, and objects in the real world that teenagers will actually encounter when they investigate further. " (pg 182)

They go on to discuss what they feel is the massive influence the film had, with an "explosive and virtually instantaneous" (pg 182) effect driving a surge of teenagers to the Pagan movement and

"[t]hat unexpected surge of teenage interest in witchcraft posed a problem for the movement in more ways than one. In the first place, it was a a wave of fascination they were largely unprepared to deal with. Modern witchcraft was not a young person's movement; few witches had any experience of dealing with teenager inquirers and no group had any kind of organized teenage outreach. In the second place the prospect of having teenagers 'convert' to witchcraft while still under their parents' roof was a hot potato, to say the least -- not just emotionally, but legally as well. Any witchcraft organization that deliberately drew a child away from its parents' religion stood a very good chance of being sued into oblivion. With that danger in mind, the witchcraft groups generally took a hands-off approach in dealing with minors. The combined result of their unreadiness and their wariness is that the organized witchcraft movement lost control of the witchcraft phenomenon in popular culture." (pg 182 and 183)

The book then deals with these "dueling" generations of Witches and their continued reconciling with one another in the movement for tolerance and recognition. The final chapter of the book meanders around the meaning of Witchcraft through the ages, particularly (of course, given the section of the book) in the modern era. It generally uses Witchcraft, religion, and magic interchangeably which is a tad irksome given that it considers among them the role of scientific theory. The book concludes on an optimistic and even whimsical

"[M]agic continues to appeal and witchcraft will not soon vanish from this earth. (pg 197)

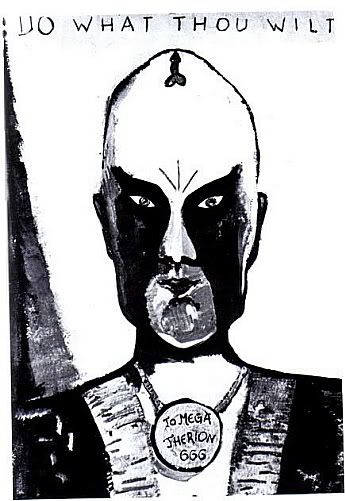

Overall, the book could use a better cohesiveness between the authors, a more evenly told first half, and the decision of what, exactly, to call, well, us, as it uses at various points pagan, neopagan, Witch, witch, and Pagan interchangeably. Still, the book boasts some thought-provoking points of view, particularly in the latter half and it is illustrated almost throughout (some are rote pics but others, including some of the pieces on Aleister Crowley are fairly rare).

Notable: While the book cites Co-National Public Information Officer Pat Devlin as a script consultant on (in the authors' opinions) the seminal The Craft, claims have been made that star Fairuza Balk also had a hand in it. Her Wiki claims (with sources) that she

"was a well known neopagan even before shooting 1996's The Craft. She provided some witchcraft information on set and helped design many of the sets to match real pagan rituals. From 1995 to 2001, she owned Panpipes Magickal Marketplace, billed as the nation's largest occult store, in Hollywood, California."

So with whom does the credit belong? A fascinating (seriously) interview with Devlin about the movie (and her defense of its various portrayals) can be found here. A lesser but still interesting interview can be found here if you can get past the numerous grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors.

Also of note is in the illustrations section wherein we find a self-portrait of Aleister Crowley:

If that doesn't give you nightmares, I don't know what will. Wait... PRESIDENT SANTORUM! PRESIDENT PALIN! PRESIDENT HUCKABEE! You're welcome.

Title: A History of Witchcraft: Sorcerers, Heretics, and Pagans SECOND EDITION by Jeffrey B. Russell and Brooks Alexander

Details: Copyright 2007, Thames & Hudson Inc

Synopsis (By Way of Back Cover): "For nearly thirty years, this book has been the authoritative illustrated history of witchcraft. Now, in collaboration with Brooks Alexander, who has himself conducted innovative research in the field, Jeffrey Russell's study has been fully revised with additional chapters accompanied by new illustrations. As history shows, whether or not one believes in witchcraft, one must believe in the existence of witches. Here, the definition of witchcraft in its many diverse forms is discussed and its historical, anthropological and religious manifestations charted from ancient times to the present. Alexander includes an analysis of the importance of the Internet and films in the dissemination of modern witchcraft and the potential tensions as a secretive, initiatory cult becomes and open and recognized religion."

Why I Wanted to Read It: Another find from Atomic Books's catalog and surprisingly a history of Paganism ("to the present") that I haven't read before.

How I Liked It: The book pleased me from the start with a line in Jeffrey B. Russell's section of the preface, wherein he states

"Whether or not one believes in the powers of witchcraft, one must believe in the existence of witches: I have known quite a few personally." (pg 7)

Why does this please me so? It's a nice change from the dismissive tones that suggest somehow we aren't "real" witches in that we don't conform to the Hollywood and storybook standard of witchcraft, that our religion(s) is/are no less real than someone claiming to be a vampire or werewolf.

The book's first section "Sorcery and Historical Witchcraft" is rather dry and at times spotty. It whisks through areas crucial to the movement of modern Paganism (such as the Romanticism of the 19th century) and lingers on the well-mined others, such as the Witchcraze in Europe and the Salem Witch Trials, both eras which have explored in varying depth by dozens of other books.

The book does pick up when it reaches the second section "Modern Witchcraft". In a book of this size, it would be impossible for this book to attempt a Triumph of the Moon level of study, but it does offer a decent overview and what Triumph doesn't, a bit of the history and evolution of various sects of Witchcraft and the "repackaging and rebranding" it's underwent (and continues to undergo) to appeal to various subcultures. The authors declare a pivotal point in the 1996 release of the film The Craft.

"The Craft is different from all previous Hollywood films about witchcraft in one important respect: it presents a picture of modern witchcraft that actually resembles the real thing, instead of being based on the standard medieval stereotypes. That is not an accident, of course, nor is it the result of merely casual research. The film's producers sought out a prominent witch from the occult community in Los Angeles to act as a consultant on the script. Pat Devin, who was then Co-National Public Information Officer for the Covenant of the Goddess (CoG), worked with Sony for two years to bring the film version of modern witchcraft substantially into line with the real-life version. The result is that, although modern Witchcraft was sensationalized for the sake of the film, it is still identifiably modern witchcraft. Despite [Pagan historian Margot]Adler's horrified reaction (she called it 'the worst movie ever made!'), The Craft turned out to be a magnet for modern witchcraft for two reasons. The first is a matter of simple psychology: the lesson of the film's 'cautionary example' (i.e., that lust for control leads to the loss of control) is largely lost on teenagers, but its dangled lure of occult power definitely is not. A sense of attraction to the dream of control (especially the dream of controlling others) is what the film lastingly conveys. The second reason is that the witchcraft in the film resembles the real thing, its lure of occult power is linked to a collection of ideas, rituals, and objects in the real world that teenagers will actually encounter when they investigate further. " (pg 182)

They go on to discuss what they feel is the massive influence the film had, with an "explosive and virtually instantaneous" (pg 182) effect driving a surge of teenagers to the Pagan movement and

"[t]hat unexpected surge of teenage interest in witchcraft posed a problem for the movement in more ways than one. In the first place, it was a a wave of fascination they were largely unprepared to deal with. Modern witchcraft was not a young person's movement; few witches had any experience of dealing with teenager inquirers and no group had any kind of organized teenage outreach. In the second place the prospect of having teenagers 'convert' to witchcraft while still under their parents' roof was a hot potato, to say the least -- not just emotionally, but legally as well. Any witchcraft organization that deliberately drew a child away from its parents' religion stood a very good chance of being sued into oblivion. With that danger in mind, the witchcraft groups generally took a hands-off approach in dealing with minors. The combined result of their unreadiness and their wariness is that the organized witchcraft movement lost control of the witchcraft phenomenon in popular culture." (pg 182 and 183)

The book then deals with these "dueling" generations of Witches and their continued reconciling with one another in the movement for tolerance and recognition. The final chapter of the book meanders around the meaning of Witchcraft through the ages, particularly (of course, given the section of the book) in the modern era. It generally uses Witchcraft, religion, and magic interchangeably which is a tad irksome given that it considers among them the role of scientific theory. The book concludes on an optimistic and even whimsical

"[M]agic continues to appeal and witchcraft will not soon vanish from this earth. (pg 197)

Overall, the book could use a better cohesiveness between the authors, a more evenly told first half, and the decision of what, exactly, to call, well, us, as it uses at various points pagan, neopagan, Witch, witch, and Pagan interchangeably. Still, the book boasts some thought-provoking points of view, particularly in the latter half and it is illustrated almost throughout (some are rote pics but others, including some of the pieces on Aleister Crowley are fairly rare).

Notable: While the book cites Co-National Public Information Officer Pat Devlin as a script consultant on (in the authors' opinions) the seminal The Craft, claims have been made that star Fairuza Balk also had a hand in it. Her Wiki claims (with sources) that she

"was a well known neopagan even before shooting 1996's The Craft. She provided some witchcraft information on set and helped design many of the sets to match real pagan rituals. From 1995 to 2001, she owned Panpipes Magickal Marketplace, billed as the nation's largest occult store, in Hollywood, California."

So with whom does the credit belong? A fascinating (seriously) interview with Devlin about the movie (and her defense of its various portrayals) can be found here. A lesser but still interesting interview can be found here if you can get past the numerous grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors.

Also of note is in the illustrations section wherein we find a self-portrait of Aleister Crowley:

If that doesn't give you nightmares, I don't know what will. Wait... PRESIDENT SANTORUM! PRESIDENT PALIN! PRESIDENT HUCKABEE! You're welcome.