The Artist's Notebook [work in progress]

Because of the caution, the discretion with which Wilde was required to write at the time, much of Basil's characterization must be conjectured and extrapolated, mostly from his remarks in the first two chapters, and in the chapter which represents the last moments of his life. These observences may be tied to queer history, life as we understand it in late Victorian England, and drawing on experiences from Oscar Wilde's own life and the art and social cultures of which he was a part. "The Artist's Notebook" is, essentially, my collection of headcanons and conjectures about the man Basil Hallward might have been and how he lived his life.

I am drawing from multiple editions of The Picture of Dorian Gray. Most notably perhaps the Harvard annotated edition, which I highly recommend in spite of it's ridiculous sensationalization as the only uncensored version of Picture. I have approximately eight other editions, the annotations of which have contributed to the content of this post.

I am also drawing from my library of Wildean and 19th century queer history as well as lectures I have attended and my association with other persons more knowledgable on the subject than myself.

Early Life

Possible Romantic History

Page from Enrique Coromina's graphic novel adaptation (French edition), which is the only time I've so blatantly seen gestures pass between Harry and Basil that would imply an intimate history.

Fixation with Dorian Gray

Wildean Martyrs: Love as Death and the Destruction of the Self in The Picture of Dorian Gray

Splash panel again from the Corominas graphic novel adaptation, depicting the brutal murder of Basil Hallward

"Dorian Gray glanced at the picture, and suddenly an uncontrollable feeling of hatred for Basil Hallward came over him, as though it had been suggested to him by the image on the canvas, whispered into his ear by those grinning lips. The mad passions of a hunted animal stirred within him, and he loathed the man who was seated at the table, more than in his whole life he had ever loathed anything. He glanced wildly around. Something glimmered on the top of the painted chest that faced him. His eye fell on it. He knew what it was. It was a knife that he had brought up, some days before, to cut a piece of cord, and had forgotten to take away with him. He moved slowly towards it, passing Hallward as he did so. As soon as he got behind him, he seized it and turned round. Hallward stirred in his chair as if he was going to rise. He rushed at him and dug the knife into the great vein that is behind the ear, crushing the man's head down on the table and stabbing again and again.

There was a stifled groan and the horrible sound of some one choking with blood. Three times the outstretched arms shot up convulsively, waving grotesque, stiff-fingered hands in the air. He stabbed him twice more, but the man did not move. Something began to trickle on the floor. He waited for a moment, still pressing the head down. Then he threw the knife on the table, and listened."

While owing much of its creative heritage to the Decadent movement in French literature, Picture is-- in its way-- a very Gothic novel. There are moments-- among pages of Aesthetic rambling about Dorian's magpie horde of rare objects d'art and Lord Henry's tiresome cynical dinner conversation-- where the book is startingly dark. It takes this turn with the suicide of Sybil Vane and ends in Dorian Gray's own suicide when he destroyes the titular portrait. But no death is as dark, as horrifically described, as the murder of Basil Hallward. I will forever be haunted by Wilde's description of the atmosphere of the schoolroom:

"He could hear nothing, but the drip, drip on the threadbare carpet. He opened the door and went out on the landing. The house was absolutely quiet. No one was about. For a few seconds he stood bending over the balustrade and peering down into the black seething well of darkness. Then he took out the key and returned to the room, locking himself in as he did so.

The thing was still seated in the chair, straining over the table with bowed head, and humped back, and long fantastic arms. Had it not been for the red jagged tear in the neck and the clotted black pool that was slowly widening on the table, one would have said that the man was simply asleep."

-- Both excerpts from this searchable e-text on Project Gutenberg

An hallucination of Basil Hallward's corpse, from the early 2000's film adaptation from which I derive my PB, showing Basil's symbolic yellow scarf, and the extent of his injuries.

Basil Hallward's Art

I have written in detail about Basil Hallward's art in another post but am in the process of revising my opinions of his work and I will move the contents of that post to this for the sake of clarity.

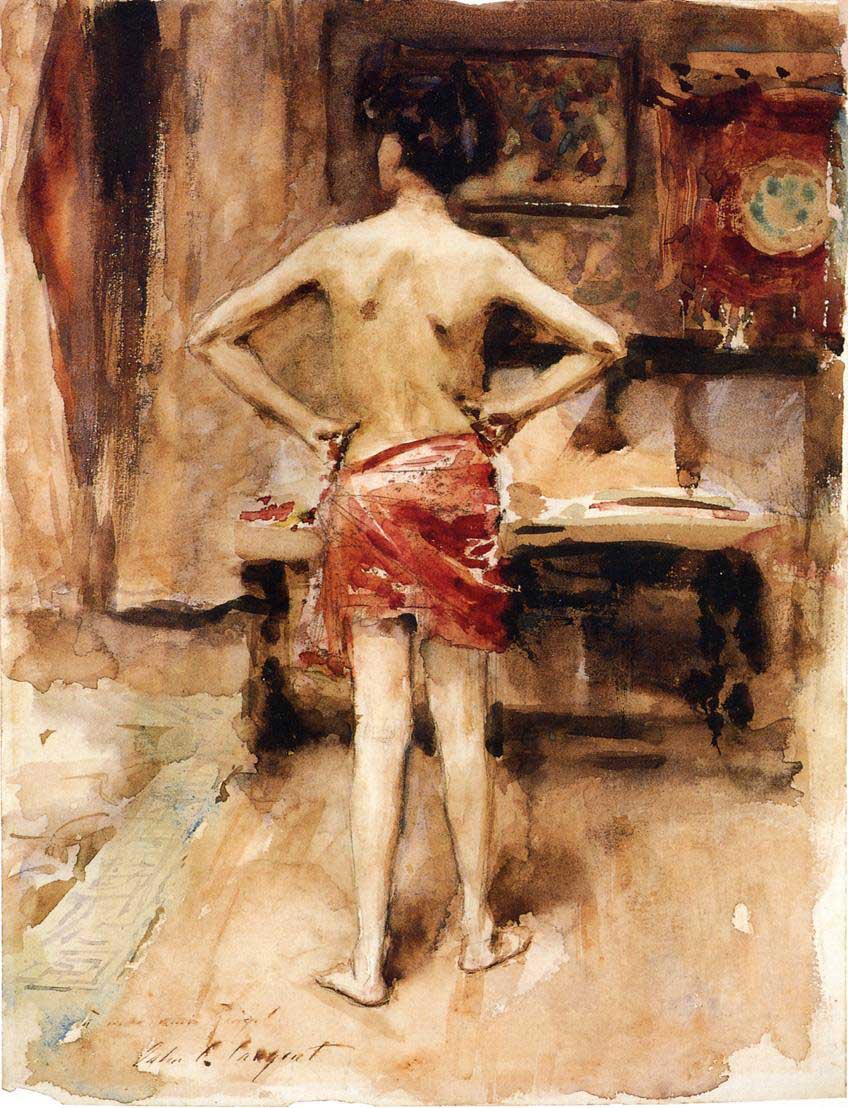

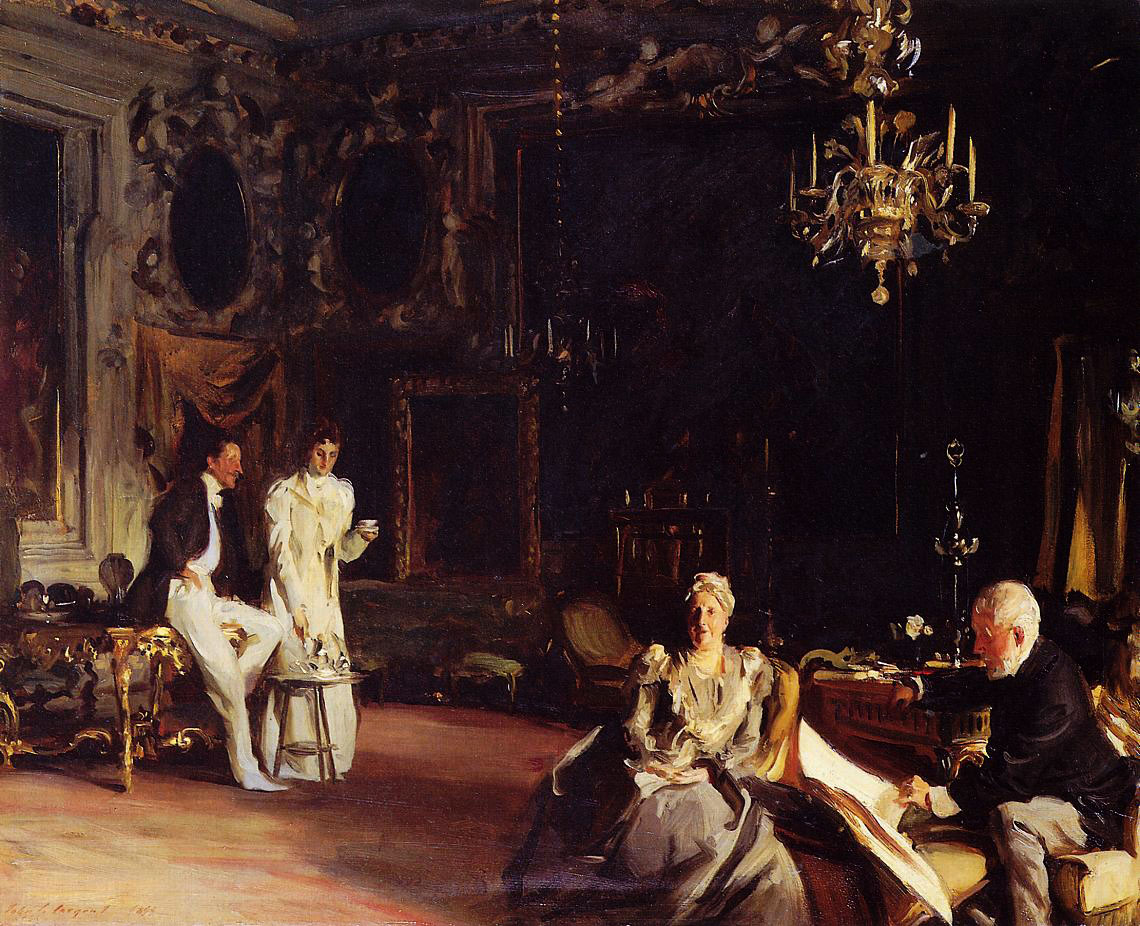

My current point of reference for Basil Hallward's painting style is heavily influenced by John Singer Sargent.

Sargent in his studio, photographed while working on Madame X, perhaps his most famous painting.I had the good fortune of attenting the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Sargent exhibit in 2015 following a lecture by Richard Ormand, one of Sargent's great-nephews and the undisputed expert on Sargent's work. I was struck by the detailed rendering of expressions and gestures in Sargent's work as well as the rich Aesthetic interiors of his portraiture.

.jpg)

Portraits of Sargent's close friend and noteworthy surgeon Dr. Pozzi known as much for his skill with a knife as for his sense of dress, being alarmingly handsome and his willingness to pose in a flashy dressing gown. If I ever needed a headcanon for Lord Henry, this is what I imagine, right down to his pointed beard.

Sargent's wikipedia article has the following quote to offer in response to the supposition that Sargent was a homosexual:

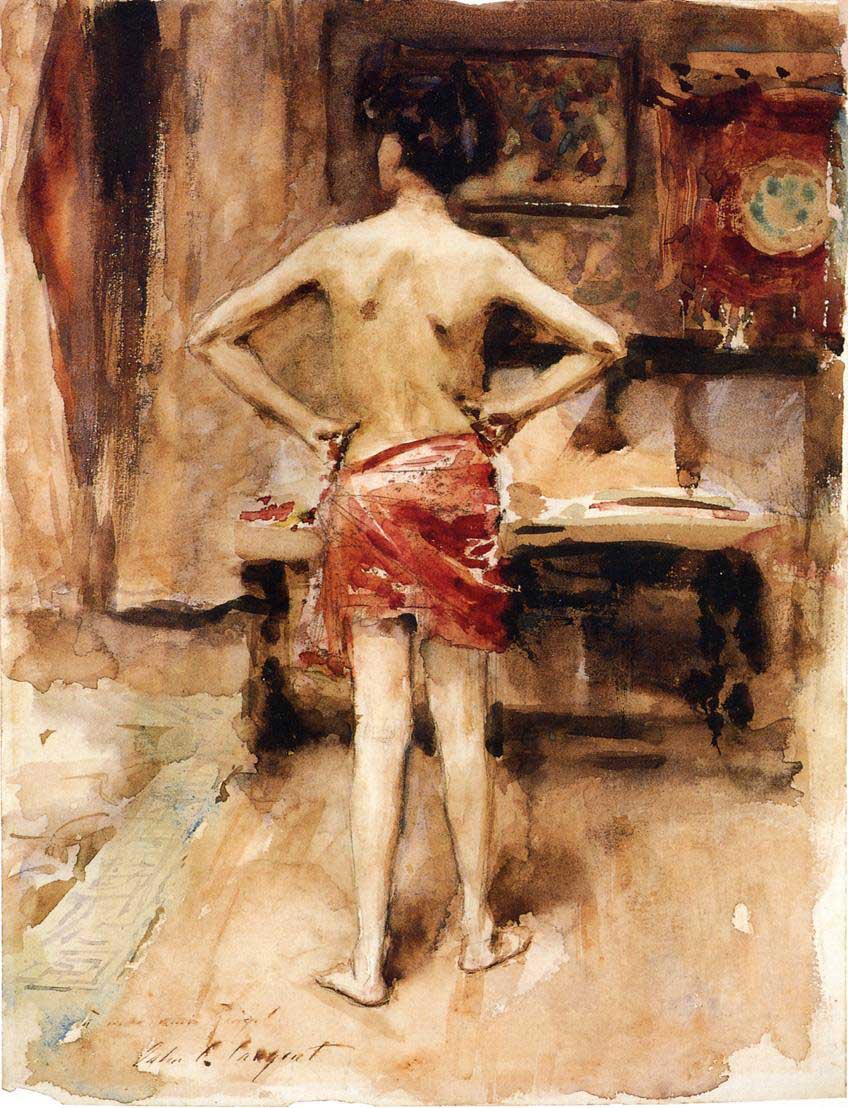

"His male nudes reveal complex and well-considered artistic sensibilities about the male physique and male sensuality".

images from the Met galleries

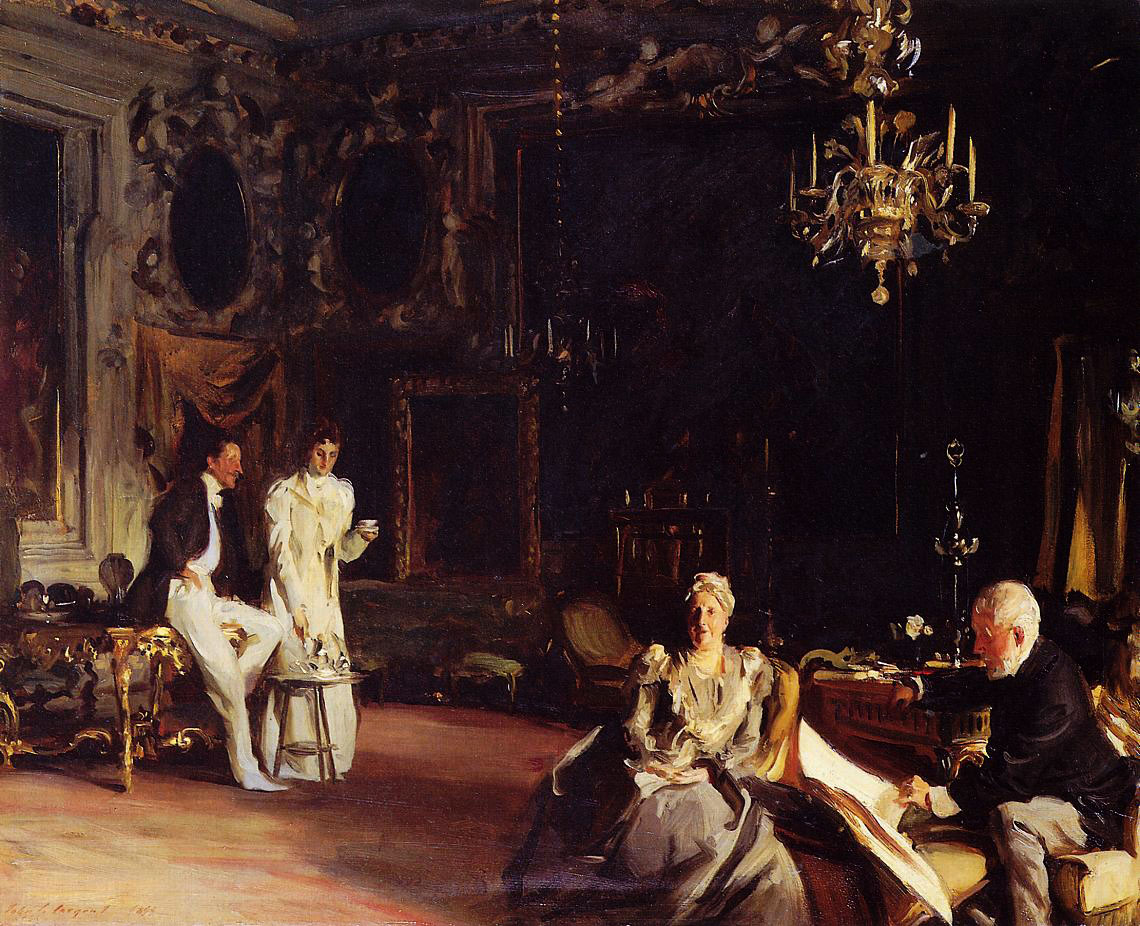

An associate whom I met at the Artists and Friends exhibit after the lecture pointed out "you don't paint someone like that if you aren't sleeping with them". He was speaking of the numerous paintings of a married couple of whom Sargent was a long-time "traveling companion", which certainly sounds like "auxillary partner" to me, and I could not deny that these paintings of the de Glehns do have a kind of intimate tenderness that makes me want to believe that somewhere they were all three of them in a bisexual triad making beautiful art and making out in fields (as a polyamrous bisexual, this might just be a weird personal bias). But my colleague made a point which ties in very closely with much of what Basil Hallward says in the first two chapters of the novel. He knows that his worshipful adoration, his love and his desire for Dorian Gray are much too obvious in the painting. He irrationally fears (or perhaps, perfectly reasonably fears) that not only with the portrait betray him for a homosexual but would also embarrassingly reveal his love to his young friend. He explains to Harry that all too often his "soul" is in his paintings, and they make clear his true nature.

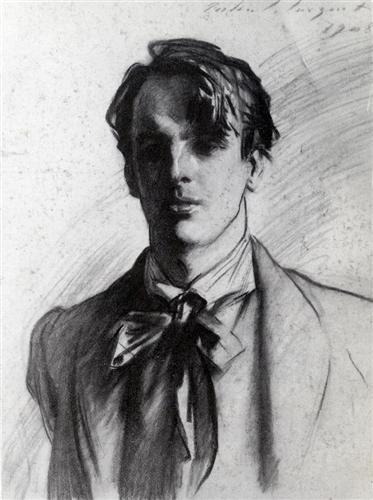

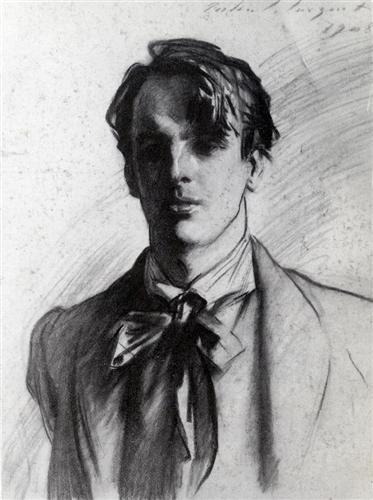

Lastly, I will close this section with the portrait which most distinctly put me in mind of Basil Hallward from the Artists and Friends exhibit. This is John Singer Sargent's portrait of the author Graham Robinson. Robinson, 28 at the time, is painted with a clear sense of youth that is almost comical.

Aesthetic Influences on Basil's Art and Life

I am drawing from multiple editions of The Picture of Dorian Gray. Most notably perhaps the Harvard annotated edition, which I highly recommend in spite of it's ridiculous sensationalization as the only uncensored version of Picture. I have approximately eight other editions, the annotations of which have contributed to the content of this post.

I am also drawing from my library of Wildean and 19th century queer history as well as lectures I have attended and my association with other persons more knowledgable on the subject than myself.

Early Life

Possible Romantic History

Page from Enrique Coromina's graphic novel adaptation (French edition), which is the only time I've so blatantly seen gestures pass between Harry and Basil that would imply an intimate history.

Fixation with Dorian Gray

Wildean Martyrs: Love as Death and the Destruction of the Self in The Picture of Dorian Gray

Splash panel again from the Corominas graphic novel adaptation, depicting the brutal murder of Basil Hallward

"Dorian Gray glanced at the picture, and suddenly an uncontrollable feeling of hatred for Basil Hallward came over him, as though it had been suggested to him by the image on the canvas, whispered into his ear by those grinning lips. The mad passions of a hunted animal stirred within him, and he loathed the man who was seated at the table, more than in his whole life he had ever loathed anything. He glanced wildly around. Something glimmered on the top of the painted chest that faced him. His eye fell on it. He knew what it was. It was a knife that he had brought up, some days before, to cut a piece of cord, and had forgotten to take away with him. He moved slowly towards it, passing Hallward as he did so. As soon as he got behind him, he seized it and turned round. Hallward stirred in his chair as if he was going to rise. He rushed at him and dug the knife into the great vein that is behind the ear, crushing the man's head down on the table and stabbing again and again.

There was a stifled groan and the horrible sound of some one choking with blood. Three times the outstretched arms shot up convulsively, waving grotesque, stiff-fingered hands in the air. He stabbed him twice more, but the man did not move. Something began to trickle on the floor. He waited for a moment, still pressing the head down. Then he threw the knife on the table, and listened."

While owing much of its creative heritage to the Decadent movement in French literature, Picture is-- in its way-- a very Gothic novel. There are moments-- among pages of Aesthetic rambling about Dorian's magpie horde of rare objects d'art and Lord Henry's tiresome cynical dinner conversation-- where the book is startingly dark. It takes this turn with the suicide of Sybil Vane and ends in Dorian Gray's own suicide when he destroyes the titular portrait. But no death is as dark, as horrifically described, as the murder of Basil Hallward. I will forever be haunted by Wilde's description of the atmosphere of the schoolroom:

"He could hear nothing, but the drip, drip on the threadbare carpet. He opened the door and went out on the landing. The house was absolutely quiet. No one was about. For a few seconds he stood bending over the balustrade and peering down into the black seething well of darkness. Then he took out the key and returned to the room, locking himself in as he did so.

The thing was still seated in the chair, straining over the table with bowed head, and humped back, and long fantastic arms. Had it not been for the red jagged tear in the neck and the clotted black pool that was slowly widening on the table, one would have said that the man was simply asleep."

-- Both excerpts from this searchable e-text on Project Gutenberg

An hallucination of Basil Hallward's corpse, from the early 2000's film adaptation from which I derive my PB, showing Basil's symbolic yellow scarf, and the extent of his injuries.

Basil Hallward's Art

I have written in detail about Basil Hallward's art in another post but am in the process of revising my opinions of his work and I will move the contents of that post to this for the sake of clarity.

My current point of reference for Basil Hallward's painting style is heavily influenced by John Singer Sargent.

Sargent in his studio, photographed while working on Madame X, perhaps his most famous painting.I had the good fortune of attenting the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Sargent exhibit in 2015 following a lecture by Richard Ormand, one of Sargent's great-nephews and the undisputed expert on Sargent's work. I was struck by the detailed rendering of expressions and gestures in Sargent's work as well as the rich Aesthetic interiors of his portraiture.

.jpg)

Portraits of Sargent's close friend and noteworthy surgeon Dr. Pozzi known as much for his skill with a knife as for his sense of dress, being alarmingly handsome and his willingness to pose in a flashy dressing gown. If I ever needed a headcanon for Lord Henry, this is what I imagine, right down to his pointed beard.

Sargent's wikipedia article has the following quote to offer in response to the supposition that Sargent was a homosexual:

"His male nudes reveal complex and well-considered artistic sensibilities about the male physique and male sensuality".

images from the Met galleries

An associate whom I met at the Artists and Friends exhibit after the lecture pointed out "you don't paint someone like that if you aren't sleeping with them". He was speaking of the numerous paintings of a married couple of whom Sargent was a long-time "traveling companion", which certainly sounds like "auxillary partner" to me, and I could not deny that these paintings of the de Glehns do have a kind of intimate tenderness that makes me want to believe that somewhere they were all three of them in a bisexual triad making beautiful art and making out in fields (as a polyamrous bisexual, this might just be a weird personal bias). But my colleague made a point which ties in very closely with much of what Basil Hallward says in the first two chapters of the novel. He knows that his worshipful adoration, his love and his desire for Dorian Gray are much too obvious in the painting. He irrationally fears (or perhaps, perfectly reasonably fears) that not only with the portrait betray him for a homosexual but would also embarrassingly reveal his love to his young friend. He explains to Harry that all too often his "soul" is in his paintings, and they make clear his true nature.

Lastly, I will close this section with the portrait which most distinctly put me in mind of Basil Hallward from the Artists and Friends exhibit. This is John Singer Sargent's portrait of the author Graham Robinson. Robinson, 28 at the time, is painted with a clear sense of youth that is almost comical.

Aesthetic Influences on Basil's Art and Life