"Beautiful" by Castorfate, commentary by Zephyrprince

Title: "Beautiful"

Vidder: Castorsfate

Fandom: Memoirs of a Geisha

Song: Sarah Brightman's "Beautiful"

Link: http://castorsfate.livejournal.com/2805.html

Commentary By: zephyrprince

The Post-Colonial Question: “Beautiful” by Castorsfate

For me, the first layer of meaning in Castorfate’s “Beautiful” is a thesis about self-worth and, unsurprisingly, beauty. Visually, the clips used in this vid alternate between footage of Sayuri as a child and her as an adult after she becomes a Geisha. The lyrics coupled with these images seem to want to say that her value is not contingent on dressing up in a certain way, wearing specific make up, or putting on a performance.

In the first shot following the title, 0:04-0:11, Sayuri is running through the torii gates, as a child.

This is compared immediately with footage of her putting on powder make up as a Geisha (0:11-0:18), putting on Geisha garb (0:18-0:21), applying ashen eyebrows (0:21-0:23), and practicing a fan dance (0:23-0:33).

All the while, the lyrics, “If you can depend on certainty, count it out and weigh it up again,” highlight the certainty, or the social and financial security, of geisha as a woman’s occupation, which is once again in stark contrast to Sayuri’s position in youth.

“You can be sure you've reached the end, and still you don't feel...”

This line speaks to the incredible journey and transformation Sayuri has gone through to reach her goal, and seems to commend her for her considerable efforts, but the clip of her gazing in the mirror suggests that in spite of this, there is still a question of whether she feels fulfilled. The lyrics then ask for the first time, “Do you know you’re beautiful?”

At 0:42 the image of her fully made-up face fades to that of her as a child being assessed by the Geisha mother, as the lyrics query a second time, “Do you know you’re beautiful?” The question is repeated, set to other clips of her appearance during the trials of her youth - being beaten, doing chores, etc. through 1:06.

In response, the lyrics “If you can ignore what you've become, take it out and see it die again, you can be here so who's a friend, and still you don't feel…” addressing for the first time the problematic nature of what she has had to submit herself to in order to gain the certainty mentioned in the first verse. This line is coupled with three clips of people taking notice of her beauty. The first is a boy on a bicycle who becomes distracted upon seeing her and crashes, the second her jealous rival, and finally clients entering the geisha house. During the line, “who’s a friend,” the piece nods to the fact that she has made some friends along the way notably, Pumpkin.

From 1:30 to 2:22, there is a long clip from her biggest performance, once again bringing to the fore the requirement that she act out the part of Geisha in order to maintain personal security and that while she the show is beautiful, so might she be without it.

The following verse introduces the last major theme for the vid - Sayuri’s relationship with Chairman Iwamora. He is brought forward by clips of their interactions starting with the scene in which he purchases a shaved ice for her when she is a child. The lyrics, “Innermost thoughts will be understood and you can have all you need,” highlight her fixation on the man from that day forward as well as the stability having a permanent patron would bring, however problematic that may also be.

From here, these same themes of childhood trauma contrasting with adulthood (physical) beauty and performance are repeated through the close of the vid with a small portion dedicated to the beautiful scenic cinematography in the film. It closes as it opens with young Sayuri running through the torii gates and a final shot of the title.

Song Choice & The Post-Colonial Question

Though I first found this vid to be aesthetically appealing (& still feel it has an apt title in that regard), what set it apart from others for me was when I started to think about how one might read the lyrics in conversation with post-coloniality. Ultimately the song choice makes this a particularly fruitful reading because the main line of the critique, the repeated chorus, is framed as a question.

Post-coloniality is actually a group of theories in several different academic disciplines that focus on the legacy of colonialism and the relationship between the West with non-Western cultures. In this case, I want to draw on the strand of post-colonial theory that seeks to make theoretical interventions into misrepresentation and misappropriation of non-Western cultures (including, here, Japanese culture although, in fact, Japan was never colonized in the same way that much of South and Southeast Asia were, for example. In fact, it was a colonizing power itself in Korea , Taiwan, and Manchuria leading up to World War II and expanding during the conflict, but Japanese people have nevertheless suffered from similar forms of Orientalism, racism, and colonial attitudes vis-à-vis the West). This brand of analysis could come into play when viding any source text that touches on non-Western culture, but it is particularly important in the context of Memoirs of a Geisha because of the problematic histories of the book and film.

First, in terms of authorship, it is notable that the framers of both the original book and the film adaptation were almost all white men. The novel was written by Arthur Golden and the screenplay adapted by Robin Swicord. The film was directed by Rob Marshall and produced by Steven Spielberg, Gary Barber, Roger Birnbaum, Douglas Wick, Lucy Fisher. I certainly do not object to their creating such a story, necessarily, but from the outset I do think it means that we have to be aware as readers and viewers that the culture being depicted - Japanese culture overall as well as Japanese women’s culture much of the time - has been filtered through outsiders’ perspective.

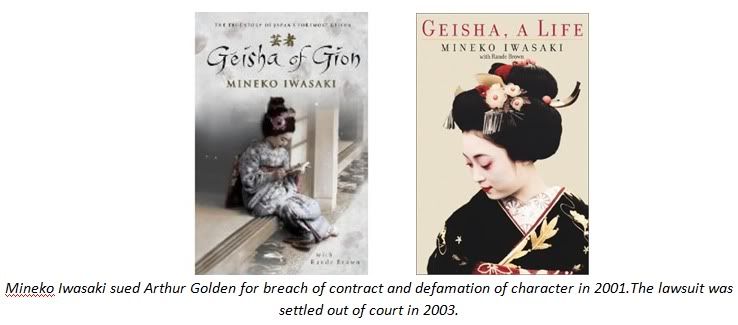

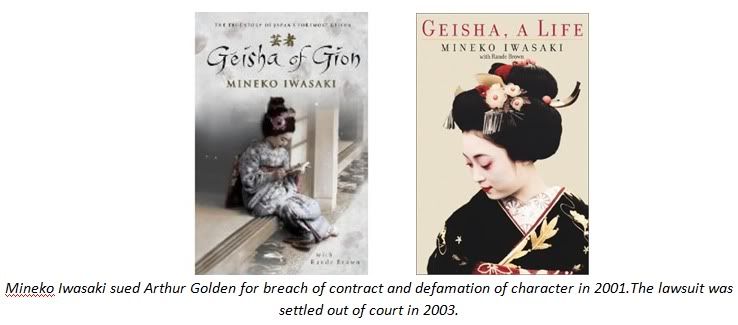

It is also crucial to note the narratives of blatant disregard for actual Japanese women involved in the making of the story. Arthur Golden, for example, took advantage of his relationship with his primary Geisha informant, Mineko Iwasaki, by revealing her name in the first edition’s acknowledgements though he had previously sworn that he would not do so because of the social taboos she was breaking in order to tell her life story. As a result, Iwasaki faced significant scorn in her home community and even received death threats. She and others in Japan were also outraged at the way elements of her narrative were twisted to make Geiko rituals appear more like prostitution. She has stated specifically, for example, that the auctioning off of Sayuri’s virginity did not happen in her own life and that she has never encountered such a custom in Gion during the 20th century. As a result of this tribulation, Iwasaki has gone on to write her own auto-biographical response to Golden’s book, Geisha of Gion or Geisha, A Life.

Similarly, when the film was being made, the non-Asian creators cast several of the Japanese characters as non-Japanese Asian actresses and actors - notably Zhang Ziyi in the starring role but also Gong Li and others. This caused controversy throughout the world because many with more familiar eyes and ears could easily tell that the actresses did not look or sound Japanese and suggested that those making the film thought all Asian people to be the same, a staple of racist Orientalist discourse. Many also felt that it was offensive to the peoples of Asia who suffered at the hands of the imperial Japanese army during World War II and before, which made up the backdrop of the story. And finally, it was decried by some who simply thought it a missed opportunity to promote Japanese talent in a major motion picture that would get exposure in the United States and the rest of the world.

Therefore, against the backdrop of all this nationality- and gender-based strife, I read this vid as one seeking analysis of Sayuri’s position as a Japanese woman in the most appropriate way possible - by asking a question and encouraging her to speak for herself. “Do you know you’re beautiful,” and the following line, “yes, you are,” say that we as viewers do not want Sayuri’s self-worth to be based on performing for men, but also does not necessarily assume that this is the case because the lyrics do not offer a conclusive answer. Perhaps Sayuri is, in fact, empowered by her choice to become a Geisha and perhaps she takes great pride in her work. Though this is not the interpretation most of us might be left with after seeing the movie, the vid understands that this could be a result of the bias of the Westerner male framers or even because of our own baggage as non-Japanese viewers (at least for those of us who are non-Japanese viewers). The vid, really then, is asking for more data straight from the original source in order to bypass the many layers of confusion lathered on to this narrative by appropriation and marketing. I might even suggest that the real answer to this vid could be read in Iwasaki’s book.

Sarah Brightman

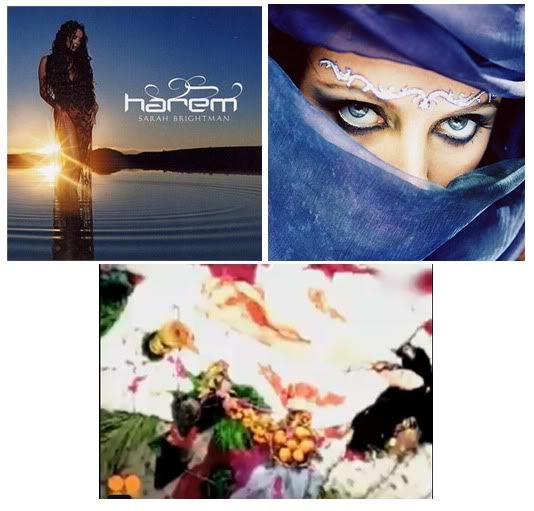

The song, “Beautiful,” was originally released in 1998 by a band called Mandalay, and the original version might have been equally appropriate in that it positions the voice of a white western female performer as the one asking the crucial question, but I find Sarah Brightman’s cover, released on her 2003 album, Harem, to be a far more interesting choice for this vid because of the ironic reappropriation of a work steeped in Orientalism.

The concept for the album was to mix Brightman’s operatic voice with Indian and Southwest Asian rhythms and vocals, which is not immediately problematic. However, the visual designs and musical influences were actually taken and mixed indiscriminately from several non-Western traditions, effectively conflating all of Asia together in a single cultural “other,” an example of classic Orientalism, as described by Edward Said and other critics. Examples include the above promotional images of Brightman wearing an Islamic hijab with her face covered; the album title, Harem, also from Islamic cultures, the visual motifs of cherry blossoms and a Japanese kimono-like garment in the music video for “Beautiful;” the inclusion of the song “Namida” on the Ultimate Edition of the album, whose title is Japanese for tears; inclusion of a Japanese version of her song “Sarahbande” on the Ultimate Edition; a collaborative song with Israeli performer, Ofra Haza; a collaboration with Iraqi singer, Kazem al-Saher; a cover of the song, “The Journey Home,” from the Indian-themed musical, Bombay Dreams, and the use of various non-Western instruments throughout the album.

This critique, however, makes it a very meaningful choice for use in a vid with such an post-colonial message. The piece can be said to reappropriate the song from an Orientalist origin point and combine it with clips from an imperialistically problematic film to create a third, more acceptable piece of media.

Conclusion: Vidding against Orientalism

Writing this, I was reminded of other vids like Shati’s “Secret Asian Man” and Lierdumoa’s “How Much is that Geisha in the Window,” both of which critique the appropriation of Chinese culture in Joss Whedon’s Firefly in light of the complete lack of Chinese characters and actors, and even Giandujakiss’ Origin Stories, exploring the positions of characters of color in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. For me, as a non-vidding fan, one of the thinks I admire most about vidders is their unique ability to dismantle Orientalism, racism, homophobia, mysogeny, and other forms of oppression through the nuance of this particular type of media criticism, which I believe this vid does in a very powerful way, reminding the keen observer to always be conscious of issues of race, gender and authorship when consuming media.

Vidder: Castorsfate

Fandom: Memoirs of a Geisha

Song: Sarah Brightman's "Beautiful"

Link: http://castorsfate.livejournal.com/2805.html

Commentary By: zephyrprince

The Post-Colonial Question: “Beautiful” by Castorsfate

For me, the first layer of meaning in Castorfate’s “Beautiful” is a thesis about self-worth and, unsurprisingly, beauty. Visually, the clips used in this vid alternate between footage of Sayuri as a child and her as an adult after she becomes a Geisha. The lyrics coupled with these images seem to want to say that her value is not contingent on dressing up in a certain way, wearing specific make up, or putting on a performance.

In the first shot following the title, 0:04-0:11, Sayuri is running through the torii gates, as a child.

This is compared immediately with footage of her putting on powder make up as a Geisha (0:11-0:18), putting on Geisha garb (0:18-0:21), applying ashen eyebrows (0:21-0:23), and practicing a fan dance (0:23-0:33).

All the while, the lyrics, “If you can depend on certainty, count it out and weigh it up again,” highlight the certainty, or the social and financial security, of geisha as a woman’s occupation, which is once again in stark contrast to Sayuri’s position in youth.

“You can be sure you've reached the end, and still you don't feel...”

This line speaks to the incredible journey and transformation Sayuri has gone through to reach her goal, and seems to commend her for her considerable efforts, but the clip of her gazing in the mirror suggests that in spite of this, there is still a question of whether she feels fulfilled. The lyrics then ask for the first time, “Do you know you’re beautiful?”

At 0:42 the image of her fully made-up face fades to that of her as a child being assessed by the Geisha mother, as the lyrics query a second time, “Do you know you’re beautiful?” The question is repeated, set to other clips of her appearance during the trials of her youth - being beaten, doing chores, etc. through 1:06.

In response, the lyrics “If you can ignore what you've become, take it out and see it die again, you can be here so who's a friend, and still you don't feel…” addressing for the first time the problematic nature of what she has had to submit herself to in order to gain the certainty mentioned in the first verse. This line is coupled with three clips of people taking notice of her beauty. The first is a boy on a bicycle who becomes distracted upon seeing her and crashes, the second her jealous rival, and finally clients entering the geisha house. During the line, “who’s a friend,” the piece nods to the fact that she has made some friends along the way notably, Pumpkin.

From 1:30 to 2:22, there is a long clip from her biggest performance, once again bringing to the fore the requirement that she act out the part of Geisha in order to maintain personal security and that while she the show is beautiful, so might she be without it.

The following verse introduces the last major theme for the vid - Sayuri’s relationship with Chairman Iwamora. He is brought forward by clips of their interactions starting with the scene in which he purchases a shaved ice for her when she is a child. The lyrics, “Innermost thoughts will be understood and you can have all you need,” highlight her fixation on the man from that day forward as well as the stability having a permanent patron would bring, however problematic that may also be.

From here, these same themes of childhood trauma contrasting with adulthood (physical) beauty and performance are repeated through the close of the vid with a small portion dedicated to the beautiful scenic cinematography in the film. It closes as it opens with young Sayuri running through the torii gates and a final shot of the title.

Song Choice & The Post-Colonial Question

Though I first found this vid to be aesthetically appealing (& still feel it has an apt title in that regard), what set it apart from others for me was when I started to think about how one might read the lyrics in conversation with post-coloniality. Ultimately the song choice makes this a particularly fruitful reading because the main line of the critique, the repeated chorus, is framed as a question.

Post-coloniality is actually a group of theories in several different academic disciplines that focus on the legacy of colonialism and the relationship between the West with non-Western cultures. In this case, I want to draw on the strand of post-colonial theory that seeks to make theoretical interventions into misrepresentation and misappropriation of non-Western cultures (including, here, Japanese culture although, in fact, Japan was never colonized in the same way that much of South and Southeast Asia were, for example. In fact, it was a colonizing power itself in Korea , Taiwan, and Manchuria leading up to World War II and expanding during the conflict, but Japanese people have nevertheless suffered from similar forms of Orientalism, racism, and colonial attitudes vis-à-vis the West). This brand of analysis could come into play when viding any source text that touches on non-Western culture, but it is particularly important in the context of Memoirs of a Geisha because of the problematic histories of the book and film.

First, in terms of authorship, it is notable that the framers of both the original book and the film adaptation were almost all white men. The novel was written by Arthur Golden and the screenplay adapted by Robin Swicord. The film was directed by Rob Marshall and produced by Steven Spielberg, Gary Barber, Roger Birnbaum, Douglas Wick, Lucy Fisher. I certainly do not object to their creating such a story, necessarily, but from the outset I do think it means that we have to be aware as readers and viewers that the culture being depicted - Japanese culture overall as well as Japanese women’s culture much of the time - has been filtered through outsiders’ perspective.

It is also crucial to note the narratives of blatant disregard for actual Japanese women involved in the making of the story. Arthur Golden, for example, took advantage of his relationship with his primary Geisha informant, Mineko Iwasaki, by revealing her name in the first edition’s acknowledgements though he had previously sworn that he would not do so because of the social taboos she was breaking in order to tell her life story. As a result, Iwasaki faced significant scorn in her home community and even received death threats. She and others in Japan were also outraged at the way elements of her narrative were twisted to make Geiko rituals appear more like prostitution. She has stated specifically, for example, that the auctioning off of Sayuri’s virginity did not happen in her own life and that she has never encountered such a custom in Gion during the 20th century. As a result of this tribulation, Iwasaki has gone on to write her own auto-biographical response to Golden’s book, Geisha of Gion or Geisha, A Life.

Similarly, when the film was being made, the non-Asian creators cast several of the Japanese characters as non-Japanese Asian actresses and actors - notably Zhang Ziyi in the starring role but also Gong Li and others. This caused controversy throughout the world because many with more familiar eyes and ears could easily tell that the actresses did not look or sound Japanese and suggested that those making the film thought all Asian people to be the same, a staple of racist Orientalist discourse. Many also felt that it was offensive to the peoples of Asia who suffered at the hands of the imperial Japanese army during World War II and before, which made up the backdrop of the story. And finally, it was decried by some who simply thought it a missed opportunity to promote Japanese talent in a major motion picture that would get exposure in the United States and the rest of the world.

Therefore, against the backdrop of all this nationality- and gender-based strife, I read this vid as one seeking analysis of Sayuri’s position as a Japanese woman in the most appropriate way possible - by asking a question and encouraging her to speak for herself. “Do you know you’re beautiful,” and the following line, “yes, you are,” say that we as viewers do not want Sayuri’s self-worth to be based on performing for men, but also does not necessarily assume that this is the case because the lyrics do not offer a conclusive answer. Perhaps Sayuri is, in fact, empowered by her choice to become a Geisha and perhaps she takes great pride in her work. Though this is not the interpretation most of us might be left with after seeing the movie, the vid understands that this could be a result of the bias of the Westerner male framers or even because of our own baggage as non-Japanese viewers (at least for those of us who are non-Japanese viewers). The vid, really then, is asking for more data straight from the original source in order to bypass the many layers of confusion lathered on to this narrative by appropriation and marketing. I might even suggest that the real answer to this vid could be read in Iwasaki’s book.

Sarah Brightman

The song, “Beautiful,” was originally released in 1998 by a band called Mandalay, and the original version might have been equally appropriate in that it positions the voice of a white western female performer as the one asking the crucial question, but I find Sarah Brightman’s cover, released on her 2003 album, Harem, to be a far more interesting choice for this vid because of the ironic reappropriation of a work steeped in Orientalism.

The concept for the album was to mix Brightman’s operatic voice with Indian and Southwest Asian rhythms and vocals, which is not immediately problematic. However, the visual designs and musical influences were actually taken and mixed indiscriminately from several non-Western traditions, effectively conflating all of Asia together in a single cultural “other,” an example of classic Orientalism, as described by Edward Said and other critics. Examples include the above promotional images of Brightman wearing an Islamic hijab with her face covered; the album title, Harem, also from Islamic cultures, the visual motifs of cherry blossoms and a Japanese kimono-like garment in the music video for “Beautiful;” the inclusion of the song “Namida” on the Ultimate Edition of the album, whose title is Japanese for tears; inclusion of a Japanese version of her song “Sarahbande” on the Ultimate Edition; a collaborative song with Israeli performer, Ofra Haza; a collaboration with Iraqi singer, Kazem al-Saher; a cover of the song, “The Journey Home,” from the Indian-themed musical, Bombay Dreams, and the use of various non-Western instruments throughout the album.

This critique, however, makes it a very meaningful choice for use in a vid with such an post-colonial message. The piece can be said to reappropriate the song from an Orientalist origin point and combine it with clips from an imperialistically problematic film to create a third, more acceptable piece of media.

Conclusion: Vidding against Orientalism

Writing this, I was reminded of other vids like Shati’s “Secret Asian Man” and Lierdumoa’s “How Much is that Geisha in the Window,” both of which critique the appropriation of Chinese culture in Joss Whedon’s Firefly in light of the complete lack of Chinese characters and actors, and even Giandujakiss’ Origin Stories, exploring the positions of characters of color in Buffy the Vampire Slayer. For me, as a non-vidding fan, one of the thinks I admire most about vidders is their unique ability to dismantle Orientalism, racism, homophobia, mysogeny, and other forms of oppression through the nuance of this particular type of media criticism, which I believe this vid does in a very powerful way, reminding the keen observer to always be conscious of issues of race, gender and authorship when consuming media.