More old News From The Age

The dying wish of an artist is for a place where her paintings, drawings and diaries can be displayed for the people of Victoria, writes James Norman.

Even from her hospital bed, artist Vali Myers, 72, and recently diagnosed with terminal cancer, dreams of the future. Myers is Australia's bohemian high priestess. Born in Sydney, she moved to Box Hill with her family when she was 11. At 19, she moved to Paris, where she spent time as a Left Bank dancer and a vagabond.

She later moved between Positano, Italy, and New York's infamous Chelsea Hotel. She was an intimate of Salvador Dali, Mick Jagger and Janis Joplin. Dali described her paintings and drawings as "excellent" and "original".

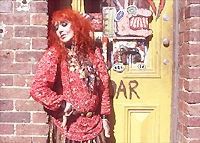

Having left Melbourne in 1949, Myers did not return until 1993, when she decided to settle here permanently. Now she lies in an inner-city hospital, ill but still wearing her trademark thick kohl eye make-up and a flower in her fierce red hair.

"I'm dying of cancer, but I may have two months left," she says frankly. "It's over my whole stomach. I appreciated that they just told me (this) straight out, here at the hospital."

Myers is hoping to fulfil one final dream. She has bequeathed her entire life's work - hundreds of paintings, sketches and vivid coloured diaries - to the state of Victoria as a gift. She hopes to find a sponsor, whether private or government, to display the work in a Vali Myers House.

"I'm going to give all my remaining work to the people of Victoria," she said. "I love it here. It's just a lovely city - the people are great, no bullshit."

Myers paintings have sold for up to $US40,000 ($A68,000) in New York. Her work is held in the Stuyvesant collection in Holland, New York's Hurryman Collection, and is owned by private collectors such as George Plimpton and Mick Jagger.

Vali Myers is nothing if not original. Her work has been described as "among the most poignant art of our time", and her art and life have inspired many local and internationally produced documentaries.

Her fine pen, ink, watercolour and gold-leaf drawings display a fastidiously rendered depiction of a personal spirit world.

Her work frequently combines human, animal and mythological motifs, rendered with psychedelic threads, and taps into primaeval themes of death, fertility, and the interconnectedness of life itself.

"I just draw - ever since I was a little girl," she says. "People always try to label it, but you can't label this work, it's original. It's like asking why do you dance? You do it because you have the spirit inside you. . . If I didn't draw I'd go mad. Artists are like shamans - they have that compulsion and nothing can stop them."

Myers' father was a marine wireless operator and her mother a violinist. As a child she danced and drew: "I was working in factories in Melbourne when I was 14 to put myself through dance school," she says. "I've always been financially independent, that's very important to me. My dad said: 'You've got to get married and have babies'. I said: 'That's what you think.' "

In 1949, Myers moved to Paris. "I went there to work, but after the war there was no work," she says. "I finished up on the streets within a week. I wasn't going to come back with my tail between my legs. It was a rough life. If you even picked up the stub of a cigarette you shared it with everybody."

During nearly 10 years in Paris, living mainly on the streets and with occasional stints in jail after being picked up by police as a vagabond, Myers came in contact with writers such as Jean Cocteau and his friend Jean Genet. But she fell seriously ill from opium addiction. "I said to my partner, 'Let's get out of Paris'. I had to get away from it.".

Darkness is a recurring theme in the art and conversation of Myers, and she described this period of opium addiction and withdrawal as "about the closest I ever came to the edge of the precipice".

"I love the dark side," she told Australian Style in 1995. "It's beautiful. It's like swimming under the sea. You don't know quite where you're going but it's beautiful. And it can be tough sometimes. You have to come up for air."

Myers fled to Italy with her husband, a handsome Hungarian gypsy named Rudi Rapport, and stumbled upon what would become her new home and place of recovery, a small property in Positano that Myers describes as "something like the Garden of Eden".

"We walked up this huge ravine (and) found an abandoned garden with little waterfalls, caves and everything, and a beautiful house," she recalls. "We had a few hundred animals there. I belong in nature and with animals."

Myers moved between her property in Italy and her other home at the infamous Chelsea Hotel in New York until the start of the 1990s. "Every time I'd saved a bit of money I'd go back to the Chelsea - I don't think any other hotel would have had me. We'd have mad drinking sessions, where bottles would end up smashed against the walls," she said.

Her visitors at the Chelsea included Debbie Harry and "a whole bunch of mad Irishmen". Myers points out, however, that the famous people she has known throughout her life were mainly chance meetings. She prefers the company of "outsiders of the streets".

Myers returned to Melbourne in 1993 and says she was delighted with the home-coming she received. "People had seen the film (Vali - The Tightrope Dancer), and, even at Tullamarine airport, people recognised me," she said.

"Melbourne is a great city. Quite old-fashioned in a way, but it's the people that make it. It's dynamite. You can strike up a conversation on a tram."

"I think a Vali Myers House would be great for Melbourne. I mean what's a house between friends? It could be self-supporting, people would come from all over the world to go there, they could buy prints, posters, films, memorabilia," said Myers.

The final impression I hold as I leave the hospital is of a woman so luminous with the spark of life as to be genuinely unperturbed by the closeness of her own death.

"I've had 72 absolutely flaming years. It doesn't bother me at all, because, you know love, when you've lived like I have, you've done it all. I put all my effort into living; any dope can drop dead," she says.

"I'm in the hospital now, and I guess I'll kick the bucket here. Every beetle does it, every bird, everybody. You come into world and then you go."