[research] Comiket report, part 1: The basics, the catalog, and keeping things fannish

Note: Comiket is an absolutely huge event, and it's going to take a couple of long posts to describe everything that interested me about it. I'm writing these posts first and foremost from a fan studies perspective, as part of my research, but they may contain traces of squee.

So, I finally got around to attending Comiket. I've made lots of short work-related visits to Japan over the last couple of years, but somehow, all of those managed to be not in August or December, when the two editions of the con take place. Meaning that I did get to attend a couple of other large dojinshi conventions (called sokubaikai or ibento), but never the Big One. Since I'm officially a researcher of the Japanese cultural economy of fanwork now, I absolutely had to attend. For science. I went together with Verena Maser, who is researching a PhD on yuri manga in Tokyo. She generously lent me a spare room and used her superior con-attending experience to make my first Comiket go off without a hitch. Thanks, Verena!

For the completely uninitiated, Comiket is a twice-yearly convention where media fans gather to sell and buy dojinshi, or printed fan comics. This fannish gathering is easily one of the biggest public events in the whole of Japan: around six hundred thousand people attend over the three days of the con, and about thirty-five thousand dojinshi creators come to sell their work. The 80th edition of Comiket took place at the Tokyo Big Sight convention center on August 12, 13, and 14. Comiket is organized by and for fans, and pretty much everyone on the staff is a volunteer. There are hundreds of these volunteers at work at any given moment, most of them helping to direct flows of people throughout the huge convention center. The word 'participants' or sankasha is used to denote everybody who takes part in some way -the volunteer staff, dojinshi creators, cosplayers, people who just come to buy, even the companies who have booths there. Organizers and attendees take great pains to emphasize that all sankasha are fellow fans who are on the same level, and nobody should behave like or expect to be treated like a customer (okyakusama).

About six weeks before each edition of Comiket, the Junbikai ('preparation committee', the volunteer group that organizes the con) publishes a new edition of the Comiket catalog, which serves as a bible for every attendee. The catalog is a gigantic, glossy, 1400-page, two-kilogram whopper that can probably double as a lethal blunt instrument.

The catalog cover, and a size comparison of the catalog with a human head:

That is my spanking new Dai Li agent hoodie, by the way. Design by jin_fenghuang, execution by a wonderful lady whose name escapes me.

About four-fifths of the catalog is filled with info on where to find each of the thousands of dojinshi sellers (sakuru or circles) that have a booth (supesu or space) at the con. The rest is a hodgepodge of explanations about Comiket do's and don'ts, helpful maps of various areas of the convention center, detailed descriptions about the various kinds of transport available, reports about the previous edition, Q&A's from attendees, and other con-related information.

Information is presented in text and/or manga format.

The catalog, in its traditional print form or as a CD-rom, can be bought at the entrance to the con for about 2500 yen. Most attendees get their catalog through mail order or from one of the designated reseller bookstores, though. Buying the monster at the door and lugging it around for a whole day is murder on the shoulders (I tried it only once), and Tokyo Big Sight is so incredibly crowded on the day of the con that there's not really any place where you can sit down and leisurely page through the catalog to figure out which circles you want to visit and where their spaces are.

Besides, the Junbikai is insistent that everyone who attends Comiket buy or borrow a catalog and take the time to check it for rule changes, important news, and so on. There is no entrance fee for the con and bringing proof that you bought a catalog is not necessary to get in, although some other dojinshi sale events do have this requirement. But there's a definite 'Read the fucking catalog' vibe to all the polite but firm and repeated entreaties to check your catalog for all the latest updates to Comiket's rules and circumstances. Newbies in particular are very strongly advised to read the whole thing before venturing into the wilderness.

As a newbie, I can say that that's excellent advice indeed. Comiket is a huge event with a lot of history and its own rules, and it can be a pretty baffling place where anyone unaware of what not to do usually ends up causing a lot of bother and aggravation to everyone around them. The catalog does a great job of helping any newcomer navigate that complex environment like a pro. Of course the Junbikai also has a website where the rules are explained and updated, although - like the catalog - it's almost entirely in Japanese. The basic rules are also available in English, Chinese, and Korean. (More about non-Japanese attendees later.)

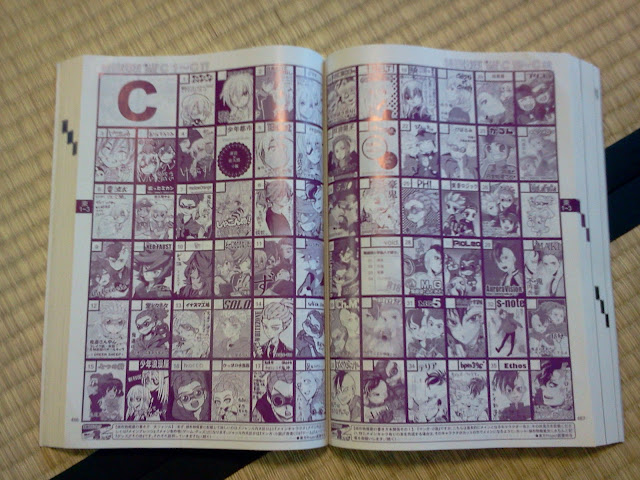

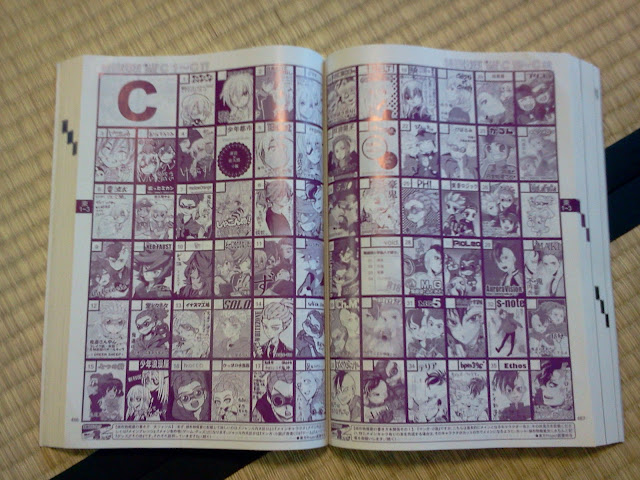

As mentioned above, the bulk of the catalog is devoted to 'circle cuts' (sakuru katto) in which each circle, which can consist of one or more dojinshi creators, briefly introduces the content they will be selling at their space during Comiket. Here's what the circle cuts look like:

These particular pages contain circle cuts for circles who make dojinshi about Inazuma Eleven, which is fast becoming one of my favorite new fandoms.

Circle cuts also include information on where in the huge convention center the circle's space (usually only half of a fold-out table in size) will be located. Given that over ten thousand circles are crammed into Tokyo Big Sight on any given Comiket day, it's pretty much impossible to find an individual circle without detailed knowledge of their space's location. Most circles have an online presence (for instance on Pixiv, the Japanese equivalent of deviantART) and announce well beforehand if they're attending Comiket and where their space will be. That means loyal readers who only attend to snap up a new work by their favorite creators may not really need the catalog's circle cuts, but most people still seem to browse through them in search of new discoveries.

Now for the rest of the catalog content. Given that one of my main research interests is the way Japanese fan communities integrate a gift economy with the large-scale sale of fanworks at places like Comiket, I was particularly interested in how Comiket and its sankasha define fannishness and deal with commercial influences. The way the catalog explains the trademarks used by Comiket already gave me a pretty good general idea:

'Comic Market', 'Comiket', and 'Comike' are all registered trademarks of Comiket Inc. You should think of these trademarks not as something that we use to enforce our rights, but as something we use to protect ourselves so that we can take action if these words are used in a way that reflects badly on Comiket. In particular, we want to limit the ways in which companies can use these words in connection with 'commercial goods'.

(Comiket catalog, p.2)

It's repeatedly emphasized throughout the catalog that Comiket is an event by and for fans, that all the rules are there to make Comiket a fun fannish experience for everyone, and that the Junbikai always makes a priority out of maximizing freedom of expression rather than restricting what people can do. For instance, this year saw some changes in the rules of cosplay to bring them more in line with this ideal. While it was previously forbidden to bring objects longer than 30cm as part of a costume, this rule has been abolished. From now on, rather than enforcing a blanket ban on potentially dangerous objects, the volunteer staff will be admonishing anyone whose actions with those objects (like swinging or throwing them around) endangers other people. In other words, they'll punishing behavior rather than pre-emptively restricting freedom of expression for everyone, including the majority of fans who act in a perfectly responsible manner.

There's also quite a few rules that are distinctly fannish in nature, instead of just generic guidelines for how to attend a very large public event. People are implored not to use trashcans inside the convention center for throwing away any fanworks they bought, because even if their purchase didn't turn out to be to their liking, the creators of the works are very attached to their 'babies' and would be hurt to see them discarded in any way. Because the staff members are all volunteers and fans themselves, all attendees are asked to be kind and considerate especially towards inexperienced staff members. These have their newbie status indicated on their name cards so everyone knows to have patience with them.

The way the company booths are introduced also serves to reinforce that the event is first and foremost a fannish one. During the whole three days of Comiket, a separate floor is reserved for various media companies to set up booths and sell goods to visiting fans (more about these in a later post). The presence of these companies at a by-the-fans event is explained as follows:

The company booths are 'a space where company participants can express themselves'. Many people may be wondering why companies are taking part in an event whose purpose is giving amateurs a place to express themselves.

At Comiket, we want to transcend the boundaries between 'professionals' and 'amateurs' and reconsider the multitude of ways in which expression can take place. We believe that even though companies aim to make a profit, they do create exchange through expression by offering products and displays.

You can find more detailed PR related to the company booths from their blurbs on p1171, or from the 'Company booths pamphlet' that is distributed for free during Comiket. (...)

(Comiket catalog, p.7)

The physical separation between the company booths and the dojinshi sellers at Comiket is mirrored in the catalog: the list of companies attending comes separately after that of the circles, and advertisements from companies are confined to the very back of the catalog. They're behind the advertisements for other dojinshi sales events, of which there are very many. I imagine that the companies may be providing some sort of sponsoring to the event as well, but since I haven't researched this properly, I won't speculate just yet.

In this edition of the Comiket catalog, a lot of general discussion was devoted to things like the new Tokyo metropolitan ordinance Bill 156 and its potential impact on Comiket (I'll be getting back to this), and how Comiket intends to collect money for victims of the March 11 disasters (see later as well). The Junbikai also put a spotlight on the problem of tetsuya, meaning people who are so eager to get into the convention center first that they camp out in the neighborhood the night before the con. This is considered dangerous for the attendees themselves, seeing as they spend the night out exposed to the elements and with a lot of cash on them. It also reflects badly on the whole con when local residents find prone bodies lying about in the street. (Apparently, it happens that people call an ambulance in the mistaken belief that a sleeping Comiket attendee is someone who's in trouble.)

One very interesting section of the catalog describes the results of a questionnaire filled in by dojinshi sellers and staff members. It contains a ton of interesting data on who the sellers are, how many dojinshi they generally manage to sell during Comiket, how much money they make or lose, and so on. I'll be describing it in detail later.

There's also an eight-page 'survival guide' about what to wear, what to eat and drink, and how to take care of oneself in order to make it through three days of Comiket without falling over. That sounds like overkill, but the con is an extremely exhausting experience, especially in the heat of summer. Wading through masses of people all day long, with no place to sit and take a break, no air conditioning, long lines in front of every vending machine and toilet, etc etc, can easily catch up even with attendees who are in perfect health. There's a popular blood donation drive held during every winter edition of Comiket, but it's absent during the summer editions because the risk of people collapsing is great enough as it is then.

The catalog also contains non-Comiket-specific information that might be of interest to dojinshi enthusiasts, like interviews with professional mangaka who also publish dojinshi and information about the Yonezawa Yoshihiro Memorial Library. This is a dojinshi and more general pop culture library that was built on the collection of the co-founder of Comiket, who passed away in 2006. I haven't managed to go to the library yet, but it sounds absolutely amazing. Yonezawa still features as a character in the little manga shorts scattered throughout the catalog and in other Junbikai publications.

Yonezawa and his manga incarnation. Images from the Yonezawa Yoshihiro Memorial Library website.

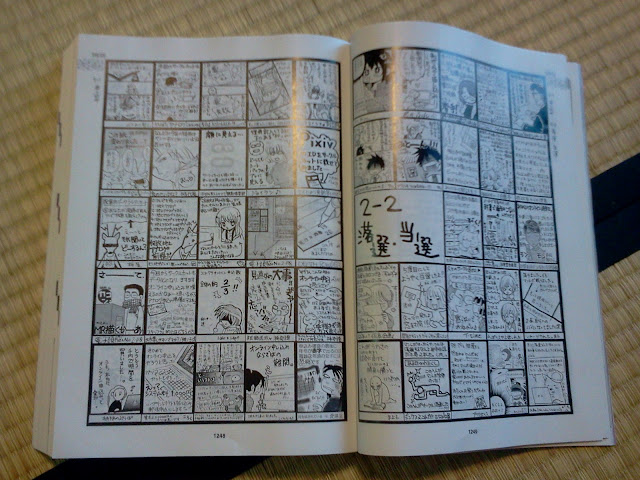

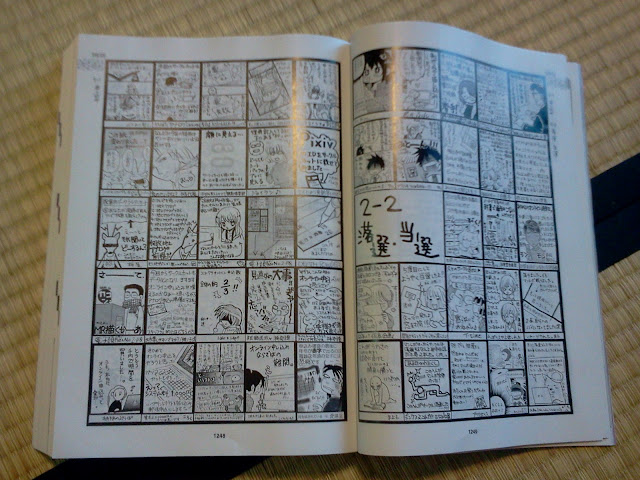

All that stuff is very interesting content, of course. But the one catalog section that I absolutely fell in love with is Manrepo, short for Manga Report. It's a glorious eighty pages stuffed with tiny cartoons (ichikoma manga) about all aspects of Comiket, sent in by people who participated in the previous edition of the con - sellers, buyers, staff, anyone who was a sankasha.

The manrepo pages are divided in sections according to topic. Above is the section header for the topic of rakusen/tosen (a circle receiving word that they've been denied or allowed a space at the next Comiket. We'll get into selection criteria for circles later). Manrepo from the 75th edition of Comiket on can also be viewed as PDF files at Comiket's website (example).

Those eighty pages of manrepo are not only highly amusing, they're probably the most informative eighty pages that have been written about Comiket anywhere. People complain about the weather and talk about what they did to ward off the heat or cold. They show how they felt when their application to take part as a circle got approved or rejected. They kvetch about the bad manners of participants who crash into others with their bags/block the aisles/offend non-fans by waving around bags with drawings of half-naked female characters on the subway after Comiket/whatnot. They talk about their experiences with the catalog, the staff, and other attendees. Manrepo from dojinshi creators explain what behavior from buyers made them happy or weirded them out. Buyers talk about the joys of chatting face-to-face with their favorite creators and the pain of arriving at a space only to find it topped by the dreaded 'sold out' (kanbai) placard. Everyone rants and raves about interesting people they met, from cosplayers to people who brought their kids to attendees who were clearly non-Japanese.

The manrepo are almost invariably funny, cute, insightful, or all of those. A couple of hours reading hundreds of manrepo probably taught me more about what to expect and how to behave at the con than most of the conversations I've had about Comiket in the past year. The translator in me was spazzing out pretty much that whole time, thinking that if I could just translate one catalog's worth of manrepo into English, I'd have a fantabulous one-stop resource for any English-speaking fan or researcher who wants to understand what goes on at a dojinshi sales convention. Of course I can't just go about scanning people's manrepo and throwing them out on the internet. But I'm keeping the idea in mind, and maybe I can suggest it to the Junbikai one day. I'm definitely going to hunt down previous catalogs just for the shiny, shiny older manrepo nuggets.

All right, that's enough about the catalog. Up next: the actual con!

This entry was originally posted at http://fanficforensics.dreamwidth.org/33967.html. Please comment there using OpenID.

So, I finally got around to attending Comiket. I've made lots of short work-related visits to Japan over the last couple of years, but somehow, all of those managed to be not in August or December, when the two editions of the con take place. Meaning that I did get to attend a couple of other large dojinshi conventions (called sokubaikai or ibento), but never the Big One. Since I'm officially a researcher of the Japanese cultural economy of fanwork now, I absolutely had to attend. For science. I went together with Verena Maser, who is researching a PhD on yuri manga in Tokyo. She generously lent me a spare room and used her superior con-attending experience to make my first Comiket go off without a hitch. Thanks, Verena!

For the completely uninitiated, Comiket is a twice-yearly convention where media fans gather to sell and buy dojinshi, or printed fan comics. This fannish gathering is easily one of the biggest public events in the whole of Japan: around six hundred thousand people attend over the three days of the con, and about thirty-five thousand dojinshi creators come to sell their work. The 80th edition of Comiket took place at the Tokyo Big Sight convention center on August 12, 13, and 14. Comiket is organized by and for fans, and pretty much everyone on the staff is a volunteer. There are hundreds of these volunteers at work at any given moment, most of them helping to direct flows of people throughout the huge convention center. The word 'participants' or sankasha is used to denote everybody who takes part in some way -the volunteer staff, dojinshi creators, cosplayers, people who just come to buy, even the companies who have booths there. Organizers and attendees take great pains to emphasize that all sankasha are fellow fans who are on the same level, and nobody should behave like or expect to be treated like a customer (okyakusama).

About six weeks before each edition of Comiket, the Junbikai ('preparation committee', the volunteer group that organizes the con) publishes a new edition of the Comiket catalog, which serves as a bible for every attendee. The catalog is a gigantic, glossy, 1400-page, two-kilogram whopper that can probably double as a lethal blunt instrument.

The catalog cover, and a size comparison of the catalog with a human head:

That is my spanking new Dai Li agent hoodie, by the way. Design by jin_fenghuang, execution by a wonderful lady whose name escapes me.

About four-fifths of the catalog is filled with info on where to find each of the thousands of dojinshi sellers (sakuru or circles) that have a booth (supesu or space) at the con. The rest is a hodgepodge of explanations about Comiket do's and don'ts, helpful maps of various areas of the convention center, detailed descriptions about the various kinds of transport available, reports about the previous edition, Q&A's from attendees, and other con-related information.

Information is presented in text and/or manga format.

The catalog, in its traditional print form or as a CD-rom, can be bought at the entrance to the con for about 2500 yen. Most attendees get their catalog through mail order or from one of the designated reseller bookstores, though. Buying the monster at the door and lugging it around for a whole day is murder on the shoulders (I tried it only once), and Tokyo Big Sight is so incredibly crowded on the day of the con that there's not really any place where you can sit down and leisurely page through the catalog to figure out which circles you want to visit and where their spaces are.

Besides, the Junbikai is insistent that everyone who attends Comiket buy or borrow a catalog and take the time to check it for rule changes, important news, and so on. There is no entrance fee for the con and bringing proof that you bought a catalog is not necessary to get in, although some other dojinshi sale events do have this requirement. But there's a definite 'Read the fucking catalog' vibe to all the polite but firm and repeated entreaties to check your catalog for all the latest updates to Comiket's rules and circumstances. Newbies in particular are very strongly advised to read the whole thing before venturing into the wilderness.

As a newbie, I can say that that's excellent advice indeed. Comiket is a huge event with a lot of history and its own rules, and it can be a pretty baffling place where anyone unaware of what not to do usually ends up causing a lot of bother and aggravation to everyone around them. The catalog does a great job of helping any newcomer navigate that complex environment like a pro. Of course the Junbikai also has a website where the rules are explained and updated, although - like the catalog - it's almost entirely in Japanese. The basic rules are also available in English, Chinese, and Korean. (More about non-Japanese attendees later.)

As mentioned above, the bulk of the catalog is devoted to 'circle cuts' (sakuru katto) in which each circle, which can consist of one or more dojinshi creators, briefly introduces the content they will be selling at their space during Comiket. Here's what the circle cuts look like:

These particular pages contain circle cuts for circles who make dojinshi about Inazuma Eleven, which is fast becoming one of my favorite new fandoms.

Circle cuts also include information on where in the huge convention center the circle's space (usually only half of a fold-out table in size) will be located. Given that over ten thousand circles are crammed into Tokyo Big Sight on any given Comiket day, it's pretty much impossible to find an individual circle without detailed knowledge of their space's location. Most circles have an online presence (for instance on Pixiv, the Japanese equivalent of deviantART) and announce well beforehand if they're attending Comiket and where their space will be. That means loyal readers who only attend to snap up a new work by their favorite creators may not really need the catalog's circle cuts, but most people still seem to browse through them in search of new discoveries.

Now for the rest of the catalog content. Given that one of my main research interests is the way Japanese fan communities integrate a gift economy with the large-scale sale of fanworks at places like Comiket, I was particularly interested in how Comiket and its sankasha define fannishness and deal with commercial influences. The way the catalog explains the trademarks used by Comiket already gave me a pretty good general idea:

'Comic Market', 'Comiket', and 'Comike' are all registered trademarks of Comiket Inc. You should think of these trademarks not as something that we use to enforce our rights, but as something we use to protect ourselves so that we can take action if these words are used in a way that reflects badly on Comiket. In particular, we want to limit the ways in which companies can use these words in connection with 'commercial goods'.

(Comiket catalog, p.2)

It's repeatedly emphasized throughout the catalog that Comiket is an event by and for fans, that all the rules are there to make Comiket a fun fannish experience for everyone, and that the Junbikai always makes a priority out of maximizing freedom of expression rather than restricting what people can do. For instance, this year saw some changes in the rules of cosplay to bring them more in line with this ideal. While it was previously forbidden to bring objects longer than 30cm as part of a costume, this rule has been abolished. From now on, rather than enforcing a blanket ban on potentially dangerous objects, the volunteer staff will be admonishing anyone whose actions with those objects (like swinging or throwing them around) endangers other people. In other words, they'll punishing behavior rather than pre-emptively restricting freedom of expression for everyone, including the majority of fans who act in a perfectly responsible manner.

There's also quite a few rules that are distinctly fannish in nature, instead of just generic guidelines for how to attend a very large public event. People are implored not to use trashcans inside the convention center for throwing away any fanworks they bought, because even if their purchase didn't turn out to be to their liking, the creators of the works are very attached to their 'babies' and would be hurt to see them discarded in any way. Because the staff members are all volunteers and fans themselves, all attendees are asked to be kind and considerate especially towards inexperienced staff members. These have their newbie status indicated on their name cards so everyone knows to have patience with them.

The way the company booths are introduced also serves to reinforce that the event is first and foremost a fannish one. During the whole three days of Comiket, a separate floor is reserved for various media companies to set up booths and sell goods to visiting fans (more about these in a later post). The presence of these companies at a by-the-fans event is explained as follows:

The company booths are 'a space where company participants can express themselves'. Many people may be wondering why companies are taking part in an event whose purpose is giving amateurs a place to express themselves.

At Comiket, we want to transcend the boundaries between 'professionals' and 'amateurs' and reconsider the multitude of ways in which expression can take place. We believe that even though companies aim to make a profit, they do create exchange through expression by offering products and displays.

You can find more detailed PR related to the company booths from their blurbs on p1171, or from the 'Company booths pamphlet' that is distributed for free during Comiket. (...)

(Comiket catalog, p.7)

The physical separation between the company booths and the dojinshi sellers at Comiket is mirrored in the catalog: the list of companies attending comes separately after that of the circles, and advertisements from companies are confined to the very back of the catalog. They're behind the advertisements for other dojinshi sales events, of which there are very many. I imagine that the companies may be providing some sort of sponsoring to the event as well, but since I haven't researched this properly, I won't speculate just yet.

In this edition of the Comiket catalog, a lot of general discussion was devoted to things like the new Tokyo metropolitan ordinance Bill 156 and its potential impact on Comiket (I'll be getting back to this), and how Comiket intends to collect money for victims of the March 11 disasters (see later as well). The Junbikai also put a spotlight on the problem of tetsuya, meaning people who are so eager to get into the convention center first that they camp out in the neighborhood the night before the con. This is considered dangerous for the attendees themselves, seeing as they spend the night out exposed to the elements and with a lot of cash on them. It also reflects badly on the whole con when local residents find prone bodies lying about in the street. (Apparently, it happens that people call an ambulance in the mistaken belief that a sleeping Comiket attendee is someone who's in trouble.)

One very interesting section of the catalog describes the results of a questionnaire filled in by dojinshi sellers and staff members. It contains a ton of interesting data on who the sellers are, how many dojinshi they generally manage to sell during Comiket, how much money they make or lose, and so on. I'll be describing it in detail later.

There's also an eight-page 'survival guide' about what to wear, what to eat and drink, and how to take care of oneself in order to make it through three days of Comiket without falling over. That sounds like overkill, but the con is an extremely exhausting experience, especially in the heat of summer. Wading through masses of people all day long, with no place to sit and take a break, no air conditioning, long lines in front of every vending machine and toilet, etc etc, can easily catch up even with attendees who are in perfect health. There's a popular blood donation drive held during every winter edition of Comiket, but it's absent during the summer editions because the risk of people collapsing is great enough as it is then.

The catalog also contains non-Comiket-specific information that might be of interest to dojinshi enthusiasts, like interviews with professional mangaka who also publish dojinshi and information about the Yonezawa Yoshihiro Memorial Library. This is a dojinshi and more general pop culture library that was built on the collection of the co-founder of Comiket, who passed away in 2006. I haven't managed to go to the library yet, but it sounds absolutely amazing. Yonezawa still features as a character in the little manga shorts scattered throughout the catalog and in other Junbikai publications.

Yonezawa and his manga incarnation. Images from the Yonezawa Yoshihiro Memorial Library website.

All that stuff is very interesting content, of course. But the one catalog section that I absolutely fell in love with is Manrepo, short for Manga Report. It's a glorious eighty pages stuffed with tiny cartoons (ichikoma manga) about all aspects of Comiket, sent in by people who participated in the previous edition of the con - sellers, buyers, staff, anyone who was a sankasha.

The manrepo pages are divided in sections according to topic. Above is the section header for the topic of rakusen/tosen (a circle receiving word that they've been denied or allowed a space at the next Comiket. We'll get into selection criteria for circles later). Manrepo from the 75th edition of Comiket on can also be viewed as PDF files at Comiket's website (example).

Those eighty pages of manrepo are not only highly amusing, they're probably the most informative eighty pages that have been written about Comiket anywhere. People complain about the weather and talk about what they did to ward off the heat or cold. They show how they felt when their application to take part as a circle got approved or rejected. They kvetch about the bad manners of participants who crash into others with their bags/block the aisles/offend non-fans by waving around bags with drawings of half-naked female characters on the subway after Comiket/whatnot. They talk about their experiences with the catalog, the staff, and other attendees. Manrepo from dojinshi creators explain what behavior from buyers made them happy or weirded them out. Buyers talk about the joys of chatting face-to-face with their favorite creators and the pain of arriving at a space only to find it topped by the dreaded 'sold out' (kanbai) placard. Everyone rants and raves about interesting people they met, from cosplayers to people who brought their kids to attendees who were clearly non-Japanese.

The manrepo are almost invariably funny, cute, insightful, or all of those. A couple of hours reading hundreds of manrepo probably taught me more about what to expect and how to behave at the con than most of the conversations I've had about Comiket in the past year. The translator in me was spazzing out pretty much that whole time, thinking that if I could just translate one catalog's worth of manrepo into English, I'd have a fantabulous one-stop resource for any English-speaking fan or researcher who wants to understand what goes on at a dojinshi sales convention. Of course I can't just go about scanning people's manrepo and throwing them out on the internet. But I'm keeping the idea in mind, and maybe I can suggest it to the Junbikai one day. I'm definitely going to hunt down previous catalogs just for the shiny, shiny older manrepo nuggets.

All right, that's enough about the catalog. Up next: the actual con!

This entry was originally posted at http://fanficforensics.dreamwidth.org/33967.html. Please comment there using OpenID.