Book Review: Woman: An Intimate Geography, 1999

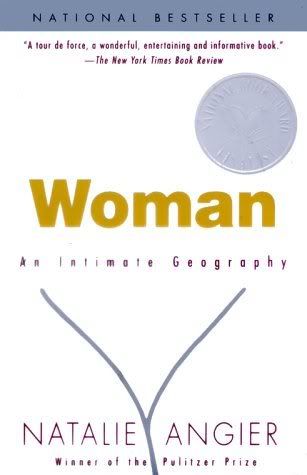

Woman: An Intimate Geography

By Natalie Angier

Published by Anchor Books, 1999

My sister, a microbiology major and total biology/science geek, gave me Woman, saying that I would love it. She said she liked it, but that she'd read only the chapter about the clitoris. She had a sly smile on her face and a brief blush to back up her recommendation. I put it aside last year in deference to other reading, but just before I left for summer vacation with my family, I picked this book up from my shelves of books waiting to be read. From the introduction to the last page, I was totally, completely enthralled.

This gorgeously written non-fiction, science-based text moves generally from the microscopic to the macroscopic: each chapter discusses the biology and sociology of the egg, the female chromosome and female fetal development, the clitoris, uterus, and breast, the ovary and hormones, and finally, more globally, the purpose of menopause in the social tribe of Homo sapiens, the innateness of aggression, and the chemistry of love. Angier, with grace, humility, and sincerity, throws off the veil of the "natural feminine" and uses her curious, aggressive eye to explain why women are what, how, and who they are without resorting to the paternal scientists' worn-out belief that women are just naturally submissive and maternal. To say the least, this book is a refreshing sight for sore eyes.

Angier writes primarily to and for women -- she assumes that most men won't be terribly interested in this sort of book about women but expresses hope that some of her audience is male -- but I don't think that Woman is inaccessible to an open-minded audience of any gender/sex. She writes from such a human, fair-minded, and logical perspective that it's difficult to take any of what she says as an offense in general or as sexist in particular. Her introduction, though, is vital to understanding her premise: "[This book] is not about the biology of gender differences and how similar or contrary men and women may be. . . . Even in Chapter 18, when I dissect some of the arguments put forth by evolutionary psychologists to explain the supposed discrepancies in male and female reproductive strategies, I'm interested less in the debate over gender differences than in challenging evolutionary psychology's anemic view of female nature. In sum, this book is not a dispatch from the front lines of the war of the sexes; it is a book about women" (xix).

I learned so much about myself reading this book. I learned about the complexity of my genes, having two X-chromosomes containing thousands of genes apiece, where men have one and a Y-chromosome, which has approximately 29 genes, whittling their genetic possibilities to half of what I have available to me -- which is neither inherently good nor inherently bad. I learned that humans -- regardless of their sex -- are aggressive at their core, and that this primary aggression informs all of our relationships, romantic, familial, or otherwise, in different ways. I learned that patriarchy as we know it came as a result of males' ability to create bonds with each other that hadn't existed before; Angier offers evidence based on chimpanzee and bonobo social research that ancient human(oid) tribes were matrifocal (not necessarily matriarchal) and that the females created networks among themselves to protect their young from jealous, controlling males. I learned that menopause may have allowed for the existence of the Grandmother -- a caretaker who can help young, new mothers as they nurse newborns, feed themselves, and continue to care for their other children. Without the Grandmother, humans may not have come to exist. And I learned that the hunter-gatherer dichotomy that privileges the hunter over the gatherer as the "Real" bringer of the bacon is a false dichotomy to some extent: in most places where humans lived in prehistory, hunting large game yielded relatively rare prizes, and whatever prizes came had to be shared among the entire tribe, not just one hunter's family. On an hour-by-hour, day-by-day, month-by-month basis, women gathering nuts and berries was what sustained the individuals of the family and tribe unit. I closed this book with a new view of biological essentialism, especially as it regards gender vs. sex, and its many hidden faults.

I recommend this book to anyone and everyone. It's a little long at 400 pages, but the individual chapters are engaging and readable as shorter pieces if 400 pages seems too daunting. Angier writes beautifully, invoking bits and pieces of feminism, gender studies, psychology, anthropology, and sociology to color and shape what would otherwise be a rather boring review of biology literature.

Woman: An Intimate Geography: A.