new model of space time?

From breakingopenthehead.com forums...

New Scientist vol 180 issue 2426 - 20 December 2003, page 40

A stash of mind-altering drugs and a near-death experience... just what a physicist needs to uncover the true nature of the universe, says Stephen Battersby...

Diagram to reference:

"FOR twelve hours I moved in and out of dimensions of both space and time. The incomprehensible became comprehensible. Realities within realities blossomed and faded. From the infinitely large to the infinitely small, unbounded and unfettered mind flashed across landscapes of incredible depth and beauty...time ceased, there was no past or future."

Well, a little brown mushroom can certainly change your outlook on life. The above is an anonymous account, posted on a website earlier this year, of the effects of consuming a hallucinogenic fungus called a psilocybe. The fungus induces what most people would consider to be an altered state of consciousness, an experience of a crazy, mixed-up universe.

But is it? Could this experience be a true reflection of reality - as true as our everyday experience of three space dimensions and one of time? Metod Saniga thinks so.

Saniga is not a professional mystic or a peddler of drugs, he is an astrophysicist at the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava. It seems unlikely that studying stars led him to such a way-out view of space and time. Has he undergone a drug-induced epiphany, or a period of mental instability? "No, no, no," Saniga says, "I am a perfectly sane person."

But a dissatisfied one. Saniga was frustrated with the kind of space-time portrayed in mainstream science - Einstein's space-time - because it does not fit with ordinary experience. Most people feel that time flows: we experience a present moment that is moving forward through time, and the past and future look very different. But according to conventional physics we inhabit a universe where time and space are frozen into a single unchanging space-time. All the events that have happened or will ever happen are marked by points in this "block" of space-time, like bubbles suspended in ice. Past and future have the same footing, and there's no flow.

Why doesn't this accord with our experience? The answer given by many philosophers of physics is that our experience of flowing time, and a distinct past and future, is an illusion. But to Saniga, this is ducking the issue. In the end, he says, science has to be based on perception: we can do experiments, but at some point we have to rely on our own perceptions to interpret the results.

If that is so, physics should be able to explain our perceived flow of time. And more than that, if subjective reality is the ultimate source of scientific data, then there are a lot of different subjective realities to take into account. Time and space can seem to behave strangely in near-death experiences, during LSD and mescaline trips, and in fits of mysticism or madness. A true picture of space and time, Saniga says, ought to encompass every possible experience.

OK, so where do we start? It's not exactly practical to try every drug going, or deliberately flirt with death. So Saniga went hunting through the literature instead.

He discovered a host of accounts written by people who had gone through peculiar states. "I take these subjective experiences to have the same standing as standard experiments and observations," he says. The experimental results you get with this attitude, however, are far from conventional.

One of the most common states described in the literature was an experience of "eternity", in which all time is compressed into the present. It can be induced by hallucinogens such as magic mushrooms, and Saniga also quotes mystics who appear to be able to put themselves into this state at will. Psychoses can lead to other strange experiences of space and time. A psychotic patient describes how time can stand still during an episode: "Time does not pass any longer. I look at the clock but its hands are always at the same position, they no longer move, they no longer go on. Then I check if the clock came to a halt. I see that it works, but the hands are standing still." (Giornale di Psichiatria e di Neuropatologia vol 95, p 765). This standstill is often accompanied by a feeling that space has lost a dimension. Everything has become flat.

In other cases the past may come to dominate, so present and future no longer exist. Time can seem to flow backwards, or even be "chaotic" - chopped into pieces and re-ordered. Taking mescaline can make time feel chaotic. In the 60s, a user wrote: "I was experiencing the events of 3.30 before the events of 3.00, the events of 2.00 after the events of 2.45, and so on. Several events I experienced with an equal degree of reality more than once." (The Drug Experience, Orion Press, New York, p 295).

There are a lot more where those came from. On a casual reading, it is difficult to see any structure in the mass of accounts, but Saniga says that you soon get the hang of it. "If you gather a large sample of such experiences you start to see a definite pattern."

And so, being mathematically minded, Saniga started to construct a geometrical model of space-time to reflect these accounts. "I was trying different structures - fractal geometry for example - but in the spring of 1995, I saw a picture in a book." That picture was of a geometrical construction called a pencil of conics, and it became the basis for Saniga's grand unified model of space-time.

To enter this altered state, you need nothing more dangerous than paper, pens and a length of spaghetti (uncooked). Or a reasonably good imagination.

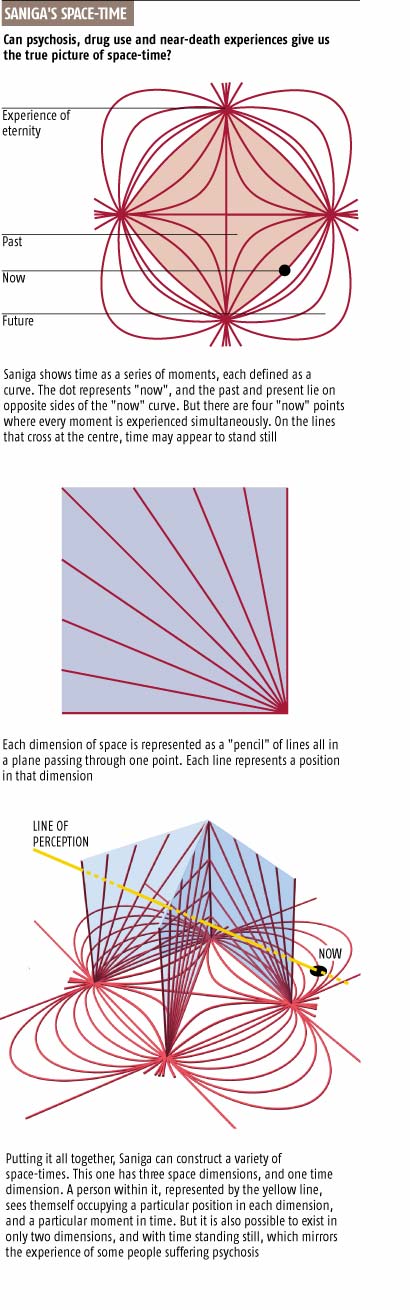

In Saniga's picture, time is rather more complicated than the straight line that you and I might visualise. It is an infinite collection of curves arranged on a plane. The curves all belong to a geometrical family called conic sections or conics, which includes circles, ellipses, parabolas and hyperbolas formed when a circular cone intersects a plane. They can be drawn on a sheet of paper in an arrangement called a pencil, in which all the different conics share four points in common (see Graphic).

Now imagine that each curve is an event, or a moment in time. Draw a little dot on the plane, on one of the lines in the pencil of conics. That is you - your point of view. You'll be sitting on one particular curve: the present moment, says Saniga. There are also an infinite number of conics that the point lies outside. Call these moments the past. And the infinite number of conics that the point lies inside?

That's the future.

Are you ready to enter an altered state now? Take the point-that-is-you, and move it so it is right on top of one of the four points in the pencil where all the curves meet. Suddenly everything changes. Now the point is exactly on every curve. According to the model, that means every moment is the present - you are experiencing the whole of time in one big fat "now". Could this correspond to the mushroom eater's feeling of eternity?

If you're feeling adventurous, you could try moving yourself to one of the two lines that join the four points and cross at the centre. These are also conic sections, but they're unlike all the other curves, and Saniga thinks they could represent time at a standstill.

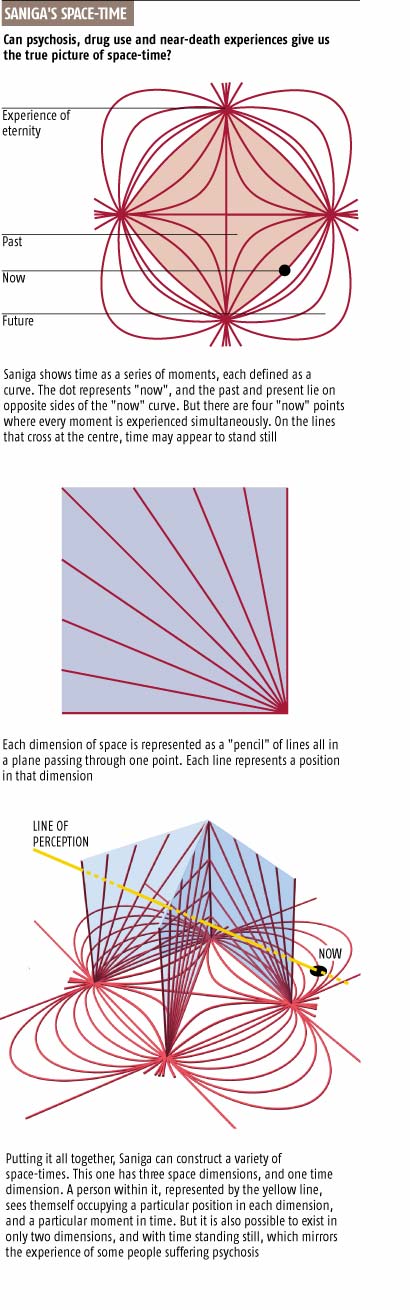

That takes care of time, but what about space? Saniga represents each space dimension as another pencil, an infinite set of straight lines all passing through one point (see Graphic). To represent three dimensions, Saniga adds three pencils of straight lines in three planes. Each line stands for a position in one of our perceived space dimensions. Draw another dot to represent yourself. Walking from your house to the shops, for example, would mean shifting the dot from one line to another line nearby.

Now move the dot all the way to the central point of the pencil. Then you would be on every line, so your perception would coincide with every place in that spatial dimension. You would feel as though all places were one place. And indeed some of the accounts describe a feeling that sounds similar.

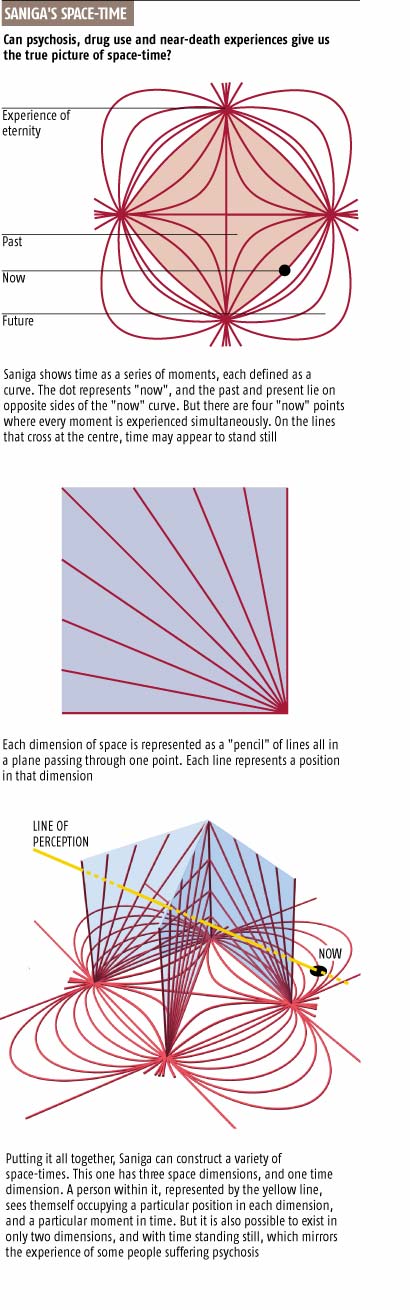

Now you are ready to put everything together and find your place in space-time. Draw a pencil of conics on one sheet of paper. Draw three pencils of lines on three more sheets, and slot them into the pencil of conics so that they share the interesting points where all the lines come together (see Graphic). This time, instead of drawing a dot to represent yourself, poke a long piece of uncooked spaghetti through the model, anywhere you like.

This is where the model begins to pay off. Now you can read off your perception of space-time by seeing where your personal spaghetti hits the different pieces of paper. If you're normal, you'll have poked it through all four pieces of paper at four unremarkable places (bear in mind that in the full model, the paper and the spaghetti are all infinite, so it is quite hard to avoid hitting all four planes). That means you find yourself at just one place in each dimension of space, and at just one time. You experience a single present moment with a memory of the past but no knowledge of the future. Well done.

But weird things can happen in Saniga's space-time setup. What if your pasta of perception hits one or more of the special lines or points on the model? You might find that you are stretched out in space or experiencing all places as one. If you hit the crossed line in the pencil of conics that intersects with the central spatial dimension, you might not see that space dimension properly - you might experience this as time standing still in a seemingly flat world.

Saniga says there are 19 distinct ways to arrange your line of perception, and claims that they fit all the different kinds of experience of time and space that have been reported. His model even puts these states into a hierarchy of strangeness, depending on how many aspects of normal perception are changed. The oddest one of all is if you poke your spaghetti exactly down the line where the three space pencils join. Then you find yourself present at every point in space, and simultaneously experiencing time as an eternal point. That, according to Saniga, is how the psilocybe mushroom eater felt.

Once you get your head around it, Saniga's grand unified space-time seems rather neat. But that does not mean it is correct. Saniga's interpretations of the subjective accounts are themselves subjective, and it isn't easy to see all the patterns he sees. The accounts are also full of contradictions. One of his mystics, for example, says: "The now that stands still is said to make eternity." This seems to be conflating two supposedly distinct states.

Might we find some objective evidence to support the model? Saniga admits that his mathematical model can't make many testable predictions. But there might be one or two. Just by glancing at the geometry, for instance, it looks as though one spatial dimension has a slightly different status from the other two. While the two outermost spatial pencils are in geometrically identical positions in the overall setup, the middle one is unique. That may imply that one dimension of our space behaves differently - that space is lopsided, in a sense.

If so, could physicists actually detect this, by some precise observations of distant quasars, or cunning experiments with lasers? "This is very difficult...I don't know," says Saniga. But earlier this year some physicists suggested that a feature of string theory called spontaneous symmetry breaking may give a "preferred" direction to space-time (New Scientist, 16 August, p 22). So a lopsided space-time is not inconceivable.

There is another hint that there may be something in Saniga's strange ideas. It comes from an abstruse bit of mathematics called Cremona transformations. These take one 3-dimensional space and distort it into a different one. It is a little like using a projector to beam a picture onto a tilted screen, distorting the two-dimensional image. In one of the simplest of these mathematical projectors, part of the necessary geometrical machinery turns out to be the set of four pencils in Saniga's model. So maybe his space-time is less arbitrary than it initially appears.

Other Cremona transformations produce entirely different kinds of space-time: dimensions with a finite number of points, or with some dimensions missing. And one of the adjustments gives a very odd picture: a universe with three dimensions of time and one of space. Saniga speculates that the universe might originally have been created this way, and only switched to three dimensions of space and one of time shortly afterwards. Could some cosmological observation identify this strange primeval space-time with its inverted dimensions? Perhaps - but there is no sign of it so far.

Einstein's space-time, though, can be used to make a lot of concrete predictions about things we can measure. And so far it fits with our observations. The way that light is deflected by galaxies, the existence of black holes (almost certainly) and gravity waves (probably), all add up to pretty good quantitative evidence.

Perhaps we should be thankful that Einstein worked out his theory while stuck in the staid surroundings of the Swiss patent office rather than during experiments with mind-altering drugs. Especially since Saniga still has not answered that original objection about the flow of time - it's not included in the model. He has certainly made a distinction between past and future, but some people think that will be explained by conventional physics, too, either in some as yet undiscovered quirk of quantum gravity, or simply because of the special state of the universe at the big bang (New Scientist, 1 November 1997, p 34).

Although Saniga's model is intriguing, it is also highly inconclusive. Indeed, while a few people interpret the model as telling us about an objective, physical space-time, far more believe that if he's really on to something then it is probably telling us about the human brain. After all, drugs and insanity don't just alter our perceptions of space and time. LSD can induce colourful kaleidoscopic visions, but no one claims that these are valid physical realities. They are just patterns created by overstimulated neurons in the visual cortex [And reality is...?]

So it is possible that Saniga's model pinpoints an unexpected connection between all sorts of different brain malfunctions: a clue to how our mind handles space and time. Some brave biologist might even find a way to relate the pencil model to brain architecture and neurotransmitters.

Saniga's interpretation is even more controversial, taking the idea of subjectivity to its logical extreme. "I believe that space-time is a characteristic of consciousness," he says. "Consciousness is more fundamental than space-time." So, having modelled the perceptions of space-time, claims Saniga, it does not make sense to ask whether this corresponds to a "real" physical universe, because that perception actually generates space and time. Does this mean there is no objective physical reality at all? "I believe that there exists what oriental philosophies call the 'absolute', which is beyond the grasp of any conceptual approach," Saniga says.

And it is here, perhaps, that Saniga starts to lose any scientific sympathy he might have gained. However, although he admits that his ideas are wildly speculative, he is unapologetic. While most scientists would say they are seeking an objective reality, Saniga thinks there is nothing scientifically wrong with taking a different tack - it might even turn out to be useful. "Normal science is based on a third-person perspective," he says, "but we need to move to a first-person perspective and put it on same basis as physical observations."

Whether you agree that it is worth making the leap really depends on your attitude to subjectivity - and Saniga's is a little different from most people's. But, hey, what's the point of subjectivity if you can't make of it what you want?

New Scientist vol 180 issue 2426 - 20 December 2003, page 40

A stash of mind-altering drugs and a near-death experience... just what a physicist needs to uncover the true nature of the universe, says Stephen Battersby...

Diagram to reference:

"FOR twelve hours I moved in and out of dimensions of both space and time. The incomprehensible became comprehensible. Realities within realities blossomed and faded. From the infinitely large to the infinitely small, unbounded and unfettered mind flashed across landscapes of incredible depth and beauty...time ceased, there was no past or future."

Well, a little brown mushroom can certainly change your outlook on life. The above is an anonymous account, posted on a website earlier this year, of the effects of consuming a hallucinogenic fungus called a psilocybe. The fungus induces what most people would consider to be an altered state of consciousness, an experience of a crazy, mixed-up universe.

But is it? Could this experience be a true reflection of reality - as true as our everyday experience of three space dimensions and one of time? Metod Saniga thinks so.

Saniga is not a professional mystic or a peddler of drugs, he is an astrophysicist at the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava. It seems unlikely that studying stars led him to such a way-out view of space and time. Has he undergone a drug-induced epiphany, or a period of mental instability? "No, no, no," Saniga says, "I am a perfectly sane person."

But a dissatisfied one. Saniga was frustrated with the kind of space-time portrayed in mainstream science - Einstein's space-time - because it does not fit with ordinary experience. Most people feel that time flows: we experience a present moment that is moving forward through time, and the past and future look very different. But according to conventional physics we inhabit a universe where time and space are frozen into a single unchanging space-time. All the events that have happened or will ever happen are marked by points in this "block" of space-time, like bubbles suspended in ice. Past and future have the same footing, and there's no flow.

Why doesn't this accord with our experience? The answer given by many philosophers of physics is that our experience of flowing time, and a distinct past and future, is an illusion. But to Saniga, this is ducking the issue. In the end, he says, science has to be based on perception: we can do experiments, but at some point we have to rely on our own perceptions to interpret the results.

If that is so, physics should be able to explain our perceived flow of time. And more than that, if subjective reality is the ultimate source of scientific data, then there are a lot of different subjective realities to take into account. Time and space can seem to behave strangely in near-death experiences, during LSD and mescaline trips, and in fits of mysticism or madness. A true picture of space and time, Saniga says, ought to encompass every possible experience.

OK, so where do we start? It's not exactly practical to try every drug going, or deliberately flirt with death. So Saniga went hunting through the literature instead.

He discovered a host of accounts written by people who had gone through peculiar states. "I take these subjective experiences to have the same standing as standard experiments and observations," he says. The experimental results you get with this attitude, however, are far from conventional.

One of the most common states described in the literature was an experience of "eternity", in which all time is compressed into the present. It can be induced by hallucinogens such as magic mushrooms, and Saniga also quotes mystics who appear to be able to put themselves into this state at will. Psychoses can lead to other strange experiences of space and time. A psychotic patient describes how time can stand still during an episode: "Time does not pass any longer. I look at the clock but its hands are always at the same position, they no longer move, they no longer go on. Then I check if the clock came to a halt. I see that it works, but the hands are standing still." (Giornale di Psichiatria e di Neuropatologia vol 95, p 765). This standstill is often accompanied by a feeling that space has lost a dimension. Everything has become flat.

In other cases the past may come to dominate, so present and future no longer exist. Time can seem to flow backwards, or even be "chaotic" - chopped into pieces and re-ordered. Taking mescaline can make time feel chaotic. In the 60s, a user wrote: "I was experiencing the events of 3.30 before the events of 3.00, the events of 2.00 after the events of 2.45, and so on. Several events I experienced with an equal degree of reality more than once." (The Drug Experience, Orion Press, New York, p 295).

There are a lot more where those came from. On a casual reading, it is difficult to see any structure in the mass of accounts, but Saniga says that you soon get the hang of it. "If you gather a large sample of such experiences you start to see a definite pattern."

And so, being mathematically minded, Saniga started to construct a geometrical model of space-time to reflect these accounts. "I was trying different structures - fractal geometry for example - but in the spring of 1995, I saw a picture in a book." That picture was of a geometrical construction called a pencil of conics, and it became the basis for Saniga's grand unified model of space-time.

To enter this altered state, you need nothing more dangerous than paper, pens and a length of spaghetti (uncooked). Or a reasonably good imagination.

In Saniga's picture, time is rather more complicated than the straight line that you and I might visualise. It is an infinite collection of curves arranged on a plane. The curves all belong to a geometrical family called conic sections or conics, which includes circles, ellipses, parabolas and hyperbolas formed when a circular cone intersects a plane. They can be drawn on a sheet of paper in an arrangement called a pencil, in which all the different conics share four points in common (see Graphic).

Now imagine that each curve is an event, or a moment in time. Draw a little dot on the plane, on one of the lines in the pencil of conics. That is you - your point of view. You'll be sitting on one particular curve: the present moment, says Saniga. There are also an infinite number of conics that the point lies outside. Call these moments the past. And the infinite number of conics that the point lies inside?

That's the future.

Are you ready to enter an altered state now? Take the point-that-is-you, and move it so it is right on top of one of the four points in the pencil where all the curves meet. Suddenly everything changes. Now the point is exactly on every curve. According to the model, that means every moment is the present - you are experiencing the whole of time in one big fat "now". Could this correspond to the mushroom eater's feeling of eternity?

If you're feeling adventurous, you could try moving yourself to one of the two lines that join the four points and cross at the centre. These are also conic sections, but they're unlike all the other curves, and Saniga thinks they could represent time at a standstill.

That takes care of time, but what about space? Saniga represents each space dimension as another pencil, an infinite set of straight lines all passing through one point (see Graphic). To represent three dimensions, Saniga adds three pencils of straight lines in three planes. Each line stands for a position in one of our perceived space dimensions. Draw another dot to represent yourself. Walking from your house to the shops, for example, would mean shifting the dot from one line to another line nearby.

Now move the dot all the way to the central point of the pencil. Then you would be on every line, so your perception would coincide with every place in that spatial dimension. You would feel as though all places were one place. And indeed some of the accounts describe a feeling that sounds similar.

Now you are ready to put everything together and find your place in space-time. Draw a pencil of conics on one sheet of paper. Draw three pencils of lines on three more sheets, and slot them into the pencil of conics so that they share the interesting points where all the lines come together (see Graphic). This time, instead of drawing a dot to represent yourself, poke a long piece of uncooked spaghetti through the model, anywhere you like.

This is where the model begins to pay off. Now you can read off your perception of space-time by seeing where your personal spaghetti hits the different pieces of paper. If you're normal, you'll have poked it through all four pieces of paper at four unremarkable places (bear in mind that in the full model, the paper and the spaghetti are all infinite, so it is quite hard to avoid hitting all four planes). That means you find yourself at just one place in each dimension of space, and at just one time. You experience a single present moment with a memory of the past but no knowledge of the future. Well done.

But weird things can happen in Saniga's space-time setup. What if your pasta of perception hits one or more of the special lines or points on the model? You might find that you are stretched out in space or experiencing all places as one. If you hit the crossed line in the pencil of conics that intersects with the central spatial dimension, you might not see that space dimension properly - you might experience this as time standing still in a seemingly flat world.

Saniga says there are 19 distinct ways to arrange your line of perception, and claims that they fit all the different kinds of experience of time and space that have been reported. His model even puts these states into a hierarchy of strangeness, depending on how many aspects of normal perception are changed. The oddest one of all is if you poke your spaghetti exactly down the line where the three space pencils join. Then you find yourself present at every point in space, and simultaneously experiencing time as an eternal point. That, according to Saniga, is how the psilocybe mushroom eater felt.

Once you get your head around it, Saniga's grand unified space-time seems rather neat. But that does not mean it is correct. Saniga's interpretations of the subjective accounts are themselves subjective, and it isn't easy to see all the patterns he sees. The accounts are also full of contradictions. One of his mystics, for example, says: "The now that stands still is said to make eternity." This seems to be conflating two supposedly distinct states.

Might we find some objective evidence to support the model? Saniga admits that his mathematical model can't make many testable predictions. But there might be one or two. Just by glancing at the geometry, for instance, it looks as though one spatial dimension has a slightly different status from the other two. While the two outermost spatial pencils are in geometrically identical positions in the overall setup, the middle one is unique. That may imply that one dimension of our space behaves differently - that space is lopsided, in a sense.

If so, could physicists actually detect this, by some precise observations of distant quasars, or cunning experiments with lasers? "This is very difficult...I don't know," says Saniga. But earlier this year some physicists suggested that a feature of string theory called spontaneous symmetry breaking may give a "preferred" direction to space-time (New Scientist, 16 August, p 22). So a lopsided space-time is not inconceivable.

There is another hint that there may be something in Saniga's strange ideas. It comes from an abstruse bit of mathematics called Cremona transformations. These take one 3-dimensional space and distort it into a different one. It is a little like using a projector to beam a picture onto a tilted screen, distorting the two-dimensional image. In one of the simplest of these mathematical projectors, part of the necessary geometrical machinery turns out to be the set of four pencils in Saniga's model. So maybe his space-time is less arbitrary than it initially appears.

Other Cremona transformations produce entirely different kinds of space-time: dimensions with a finite number of points, or with some dimensions missing. And one of the adjustments gives a very odd picture: a universe with three dimensions of time and one of space. Saniga speculates that the universe might originally have been created this way, and only switched to three dimensions of space and one of time shortly afterwards. Could some cosmological observation identify this strange primeval space-time with its inverted dimensions? Perhaps - but there is no sign of it so far.

Einstein's space-time, though, can be used to make a lot of concrete predictions about things we can measure. And so far it fits with our observations. The way that light is deflected by galaxies, the existence of black holes (almost certainly) and gravity waves (probably), all add up to pretty good quantitative evidence.

Perhaps we should be thankful that Einstein worked out his theory while stuck in the staid surroundings of the Swiss patent office rather than during experiments with mind-altering drugs. Especially since Saniga still has not answered that original objection about the flow of time - it's not included in the model. He has certainly made a distinction between past and future, but some people think that will be explained by conventional physics, too, either in some as yet undiscovered quirk of quantum gravity, or simply because of the special state of the universe at the big bang (New Scientist, 1 November 1997, p 34).

Although Saniga's model is intriguing, it is also highly inconclusive. Indeed, while a few people interpret the model as telling us about an objective, physical space-time, far more believe that if he's really on to something then it is probably telling us about the human brain. After all, drugs and insanity don't just alter our perceptions of space and time. LSD can induce colourful kaleidoscopic visions, but no one claims that these are valid physical realities. They are just patterns created by overstimulated neurons in the visual cortex [And reality is...?]

So it is possible that Saniga's model pinpoints an unexpected connection between all sorts of different brain malfunctions: a clue to how our mind handles space and time. Some brave biologist might even find a way to relate the pencil model to brain architecture and neurotransmitters.

Saniga's interpretation is even more controversial, taking the idea of subjectivity to its logical extreme. "I believe that space-time is a characteristic of consciousness," he says. "Consciousness is more fundamental than space-time." So, having modelled the perceptions of space-time, claims Saniga, it does not make sense to ask whether this corresponds to a "real" physical universe, because that perception actually generates space and time. Does this mean there is no objective physical reality at all? "I believe that there exists what oriental philosophies call the 'absolute', which is beyond the grasp of any conceptual approach," Saniga says.

And it is here, perhaps, that Saniga starts to lose any scientific sympathy he might have gained. However, although he admits that his ideas are wildly speculative, he is unapologetic. While most scientists would say they are seeking an objective reality, Saniga thinks there is nothing scientifically wrong with taking a different tack - it might even turn out to be useful. "Normal science is based on a third-person perspective," he says, "but we need to move to a first-person perspective and put it on same basis as physical observations."

Whether you agree that it is worth making the leap really depends on your attitude to subjectivity - and Saniga's is a little different from most people's. But, hey, what's the point of subjectivity if you can't make of it what you want?