Let Me Hear Your Body Talk

Wings melting, he closed his eyes as he plunged toward the sea; the image of the sun still burned in his memory. He had dared.

Struggling, he was condemned to bear the weight of the heavens; challenging the gods always had its price. He had dared.

Within minutes of its opening, “Unvanquished” presents us with two figures from Greek mythology (three, if you count the Daniel/Phaeton/son of Phoebus connection) who dared to transgress and, as a result, suffered weighty consequences. The gods of antiquity, it seemed, were not kind to those who opposed the natural order of things. On one level both of these stories speak to a notion of control-the manifestation of patriarchal hegemony in the form of story-but we can also think about how these two characters form a bridge between heaven and earth through their bodies.

Religion (and, I would argue, strains of philosophy in general) has continually attempted to explore the role and purpose of the physical body (Coakley 1997, Dennett 1978, McGuire 2003), in effect attempting to define the relationship of the body to heaven and earth. Centuries of discussion have resulted in a plethora of outcomes and no definitive answer; the body continues to serve as a site of contestation in a struggle that is portrayed beautifully in “Unvanquished.”

In particular, our class seemed to gravitate toward Barnabas as he convened with his cell in a blood ritual (you can find mentions here, here, here, and here). Blood has previously played a very particular role in the series, suggests Anthea Butler, both as a figurative term and a literal commodity (2010). I would argue that Butler’s arguments, although originally applied to another episode, hold true for “Unvanquished” as well; while not as overtly blood-filled as “Pyramid Scheme,” punishment of the body raises interesting notions regarding the role of the physical and material in the context of religion.

For example, what view must one take of the body in order to become a suicide bomber? Is the body nothing more than the instrument of God? Is the body something to be sacrificed in the ongoing struggle as one religion attempts to battle another?

But we also understand that religion isn’t necessarily about prayers, God, and churches (although it certainly can be): we are, at one point, exposed to lingering shots of Tauron tattoos in a sequence that evokes notions of the male gaze as traditionally applied to female bodies. We understand that the tattoos of the Taurons are inextricably linked with religious ritual (see “There Is Another Sky”) but also with achievements and rites of a more secular sort. In their own way, we can see these tattoos as evidence of what Stig Hjarvard terms “banal religion” (2008), a phrase that helps us to understand the forms of religion that exist outside of traditional interpretations. However, unlike Barnabas, who considers the body as an entity without meaning (and arguably detestable), Taurons have been shown to regard their bodies as an integral part of their religion; the body is literally the site upon which religion is enacted and recorded.

This episode also exposed us to the machinations of Clarice, who championed the rather complex notion of apotheosis: while Clarice talked about grand notions of heaven, true believers were still embodied as virtual avatars. Clarice, then, offers a trade of sorts: a material body for an incorruptible one. Rather than advocate for a religion mired in conventional notions of heaven and earth, Clarice chooses a path that has one foot placed firmly in both realms; Clarice believes in elevation, transformation, and transcendence of the body.

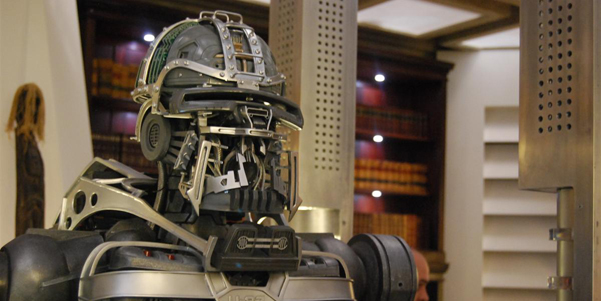

Finally we also see a contrast between the manufactured bodies of the U-87s and the, in some ways, very fallible bodies of humans. The episode opens with a sequence of shots that allow us to glimpse the U-87 manufacture process-these, as we are told, are the next generation of bodies that will not need sleep or food. In contrast, we see human bodies in disrepair a la Daniel Graystone but are also reminded, as one student noted, that even mechanical bodies are subject to burial. What do we make of the fact that this particular body once held the spark of life? Is this body merely a golem that has lost its breath?

U-87

And, ultimately, what is “unvanquished”? Our bodies? Our spirits? The term as we understand it could certainly be applied to a number of entities in this episode: Daniel, Clarice, the religion of the OTG, Amanda, Zoe, and the concept of faith all seem worthy of this descriptor. In their own way, each of these people or ideas had dared to challenge the status quo and has been met with resistance and hostility; down, but not out, we see the struggle for survival continue.

As we continue to delve into the rest of Season 1.5, the issue of bodies will be an interesting one to keep in mind. What will transpire, for example, when the “dead walkers” become more well known? Reports of them are sure to flood through Caprica and what will Clarice do when she realizes that her dream of apotheosis has been achieved? Will people choose to live on as code-as a digital representation-rather than consign themselves to the strain of mortal life? What is the function of religion in the lives of the inhabitants of Caprica? What of Zoe’s thoughts on generations and fractals? If she understands how to make trees more “treelike,” might she not also be able to make heaven more “heavenlike”? The possibilities with code are seemingly endless, limited only by our ability to manipulate it. Will this cause us to become disenchanted with the world? Classmates have debated about the relationship between technology and enchantment (here and here) along with the general ability of Caprica to re-enchant the world. Who is winning in the ideological war between reason and faith? Or are we merely misunderstanding the issue entirely? Our class also looks at the presence of ritual in the show, from the overt (the aforementioned Barnabas), to the rituals of sport and the mediatized ritual of channel surfing.

Culling together our knowledge through class discussions and blogs, we hope to increase our understanding of religion in Caprica. Although we have an entire demi-season in front of us, there is also much to be gleaned from the show’s previous offerings. My hope is that classmates will build upon their arguments and the positions of others, synthesizing the discussion (and their burgeoning knowledge of the show) into posts that allow us, as a class, to reflect on salient themes.