The labyrinths of Limehouse.

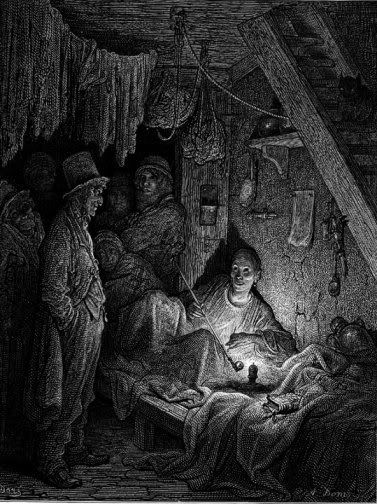

Across the court and up another dark little staircase into "Johnson's" dirty bedroom. Johnson is a Chinaman, but he has an English "wife," who sits before the fire grumbling - because they have to pay 4s. a week for a house that lets in the rain. There are a few dirty prints on the walls, and a little oblong chimney-glass, with the backing almost worn off. On the dirty bed reclines Johnson, a corpse-complexioned, sapless-looking man, whose face twitches as if he had the tic douloureux until he succeeds in lighting his charge of opium. When asked why he smokes opium, he answers that he could not "go to sillip" (sleep) if he did not smoke it, and when an inquiry is made as to the number of pipes he could smoke in a day, he says five hundred dozen, if he could get them. A Chinese lodger, in Chinese costume (a slender, taper-fingered, black-moustached, almost obsequiously polite young fellow, who is sitting at a little table reading a Chinese history of the Taiping Rebellion), bares his white, gleaming teeth in a broad smile when he hears his landlord give this hyperbolical estimate of his powers. The two Chinamen cannot talk to each other in Chinese, as they come from different provinces. From what they say to each other and ourselves in "pigeon English," we gather that the lodger came over to England as a ship's cook, and is now staying to see a little of the country, supporting himself by selling penny packets of scent in the streets. At Johnson's hint he brings out the box in which he keeps his stock, and soon disposes of sundry little white and pink parcels of some atrociously sickly-scented stuff. Johnson next shows us the modicums of opium, which he sells his customers for 6d., 8d., 1s. 6d., and so on, and then taking a stickless gas-candle, he shambles off the bed and down his narrow staircase, to light us out. As he stands at his doorway and looks out into the fog, he holds the candle above his head. When the light falls on his filmy-eyed, twitching; sickly-yellow face, it looks not unlike that of a galvanised corpse.

On another night Johnson is in his ground-floor room, and calls out cheerily, "Come in," as soon as he hears us at the door. He is lolling on a bed-tick divan, made out of a greasy bed and mattress placed on the floor and against the wall. He is in high good humour, almost constantly joking and laughing. Now he takes a pull at the opium-pipe, and then he puts it into the mouth of a drowsy Lascar, who begins to smoke with his head on the legs of another Lascar who is lying as motionless as a log. Johnson manages the lamp for his lazy customer, and meanwhile smokes a cheroot. A slight Chinese sailor, who has had his dose, stands up in the middle of the room chuckling at anything and nothing. A more powerful fellow, of a negro-like complexion and cut of countenance, who says that lie comes from Singapore, has also had his dose. He sits musing by the divan for a minute, and then gets up and seats himself before the fire, where he begins a song of the kind the tom-tom players sing. Johnson says, approvingly, "Nice - very good cantic," and then he and the two Lascars and the Chinaman burst out laughing, in that dingy little hole, as if care, for them, were banished from the world.

(from Rowe, R. Life in the London Streets, 1881, pp. 40-43)

I want to go to an opium den. They sound bitchin'.

On another night Johnson is in his ground-floor room, and calls out cheerily, "Come in," as soon as he hears us at the door. He is lolling on a bed-tick divan, made out of a greasy bed and mattress placed on the floor and against the wall. He is in high good humour, almost constantly joking and laughing. Now he takes a pull at the opium-pipe, and then he puts it into the mouth of a drowsy Lascar, who begins to smoke with his head on the legs of another Lascar who is lying as motionless as a log. Johnson manages the lamp for his lazy customer, and meanwhile smokes a cheroot. A slight Chinese sailor, who has had his dose, stands up in the middle of the room chuckling at anything and nothing. A more powerful fellow, of a negro-like complexion and cut of countenance, who says that lie comes from Singapore, has also had his dose. He sits musing by the divan for a minute, and then gets up and seats himself before the fire, where he begins a song of the kind the tom-tom players sing. Johnson says, approvingly, "Nice - very good cantic," and then he and the two Lascars and the Chinaman burst out laughing, in that dingy little hole, as if care, for them, were banished from the world.

(from Rowe, R. Life in the London Streets, 1881, pp. 40-43)

I want to go to an opium den. They sound bitchin'.