Heroism and Mike Carey's Mazikeen.

A quiet Saturday. Supposed to be helping my father fix the garage door, but it was raining and, like a particularly house-bound cat, I'm loathe to go outside and get my paws dirty. Instead, I've been reading old reviews and commentary of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and in the process, came across this long essay titled "Making Women Warriors: a transnational reading of Asian female action heroes". In it, I found this passage:

Heroism is culturally specific. Where U.S. action films uphold rugged individualism, often extolling the “gumption” of renegade cops, those on the fringe of society, and proverbial (and literal) cowboys, heroes in Asian films are considered heroic because they place loyalty to another person, clan, or community above all else. Their heroism comes from the ability to do for others, not for the self; victory comes from sacrifice for the group, not from self-aggrandizement. ... In Asian film, heroism usually means sacrifice, often to the death, and particularly for the lead character. At the end of U.S. action films, the hero almost always lives, victorious. (Sidekicks and supporting players may die, but rarely does the leading man.) The Asian hero proves her/his worth, her/his heroism, by living up to a filial pledge to a larger order, and heroic action is practiced for a higher ideal.

It occurred to me that this idea of heroism as "loyalty [and] sacrifice" is central to how I view the character of Mazikeen in Mike Carey's Lucifer. In terms of the conventions set out in this essay, Lucifer can be seen as the archetypal Western hero, determined to be free, while Mazikeen is his Eastern counterpart, yin to his yang. Pledging her loyalty and service to Lucifer, Mazikeen fights literally to the point of death against Cestis of the Jin En Mok to defend Lucifer's trump card against God (a gate that allows him to exit Creation), and is only brought back by the Basanos and Jill Presto.

Mazikeen, of course, doesn't quite fit the stereotype since, in throwing her lot with Lucifer, she was putting him above her loyalty to her community and family - the Lilim. (My thoughts about this are clearly long-standing: An Invention, in Parts, which I wrote more than four years ago, centres on just this crucial decision.) This conflict of loyalties is also played out in the graphic novel. After her near-death experience, Lucifer's refusal to make sacrifices for her in return, and the return of the Lilim, sees Mazikeen briefly appearing as her lover's antagonist, as she leads the Lilim in their land-grabbing campaign.

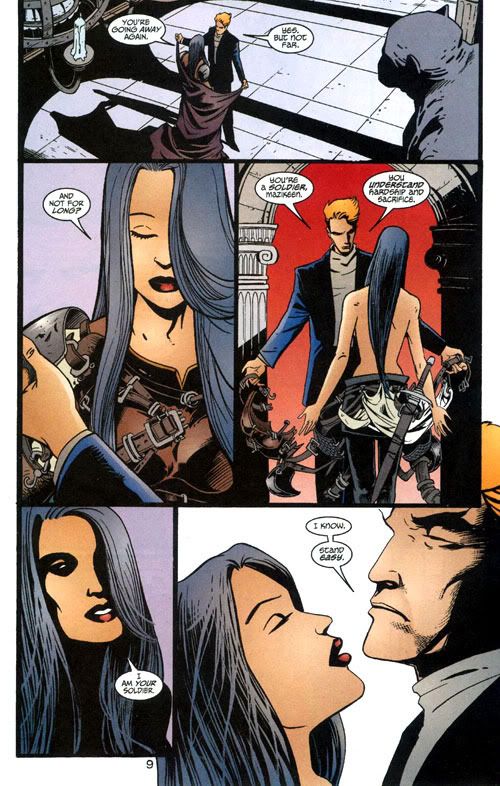

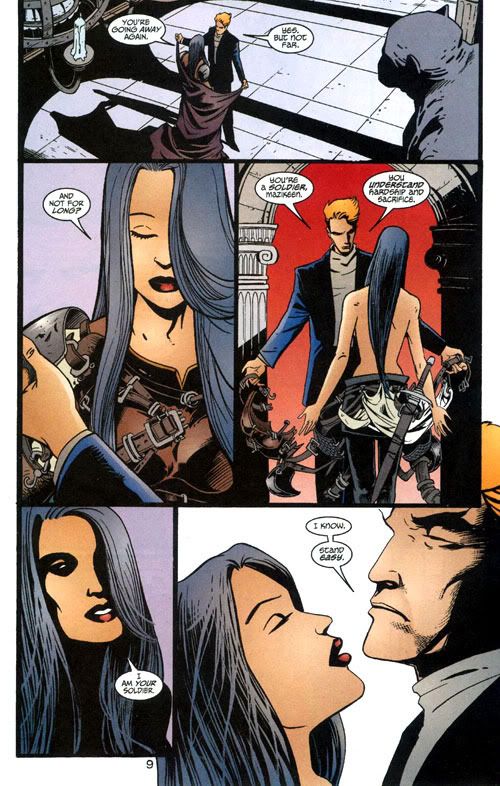

What's so wonderful about their relationship is that Mazikeen's assertion of her own desires and identity (her "face"), which lead her away from Lucifer, is also what prompts Lucifer to begin his reevaluation of her. By the time she returns to him (in "Come to Judgement" #34), having played a key role in saving his life, literally handing him the skull of his enemy, they've already reached a new level of equilibrium. (Scans courtesy of so_spiffed.)

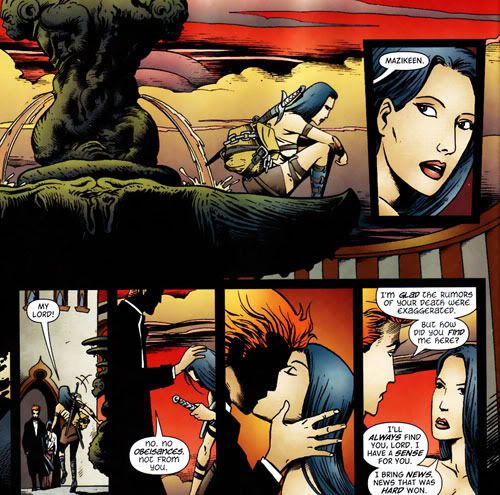

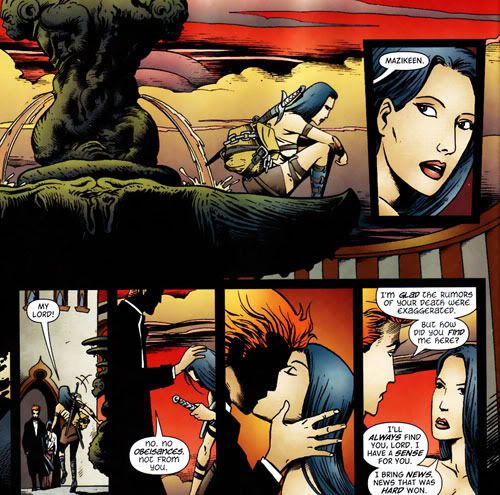

From his consort, to his lieutenant. And by "Morningstar" (#63-65), as they reunite when the stakes are higher still, she has become even more than that:

To bring it back to the essay that started off this training of thought, I suppose my point is that Mazikeen's death was "heroic" (in the Eastern sense), but had her story ended there - had she never been resurrected - we would never have learnt what she had given up to follow the one she loved and worshipped. We would never have known the Mazikeen that was so memorably strong and independent in later issues, the Mazikeen that Lucifer felt such affinity with. She would have forever remained "Lucifer's whore". Dying was not enough to make her a hero; she had to live.

Heroism is culturally specific. Where U.S. action films uphold rugged individualism, often extolling the “gumption” of renegade cops, those on the fringe of society, and proverbial (and literal) cowboys, heroes in Asian films are considered heroic because they place loyalty to another person, clan, or community above all else. Their heroism comes from the ability to do for others, not for the self; victory comes from sacrifice for the group, not from self-aggrandizement. ... In Asian film, heroism usually means sacrifice, often to the death, and particularly for the lead character. At the end of U.S. action films, the hero almost always lives, victorious. (Sidekicks and supporting players may die, but rarely does the leading man.) The Asian hero proves her/his worth, her/his heroism, by living up to a filial pledge to a larger order, and heroic action is practiced for a higher ideal.

It occurred to me that this idea of heroism as "loyalty [and] sacrifice" is central to how I view the character of Mazikeen in Mike Carey's Lucifer. In terms of the conventions set out in this essay, Lucifer can be seen as the archetypal Western hero, determined to be free, while Mazikeen is his Eastern counterpart, yin to his yang. Pledging her loyalty and service to Lucifer, Mazikeen fights literally to the point of death against Cestis of the Jin En Mok to defend Lucifer's trump card against God (a gate that allows him to exit Creation), and is only brought back by the Basanos and Jill Presto.

Mazikeen, of course, doesn't quite fit the stereotype since, in throwing her lot with Lucifer, she was putting him above her loyalty to her community and family - the Lilim. (My thoughts about this are clearly long-standing: An Invention, in Parts, which I wrote more than four years ago, centres on just this crucial decision.) This conflict of loyalties is also played out in the graphic novel. After her near-death experience, Lucifer's refusal to make sacrifices for her in return, and the return of the Lilim, sees Mazikeen briefly appearing as her lover's antagonist, as she leads the Lilim in their land-grabbing campaign.

What's so wonderful about their relationship is that Mazikeen's assertion of her own desires and identity (her "face"), which lead her away from Lucifer, is also what prompts Lucifer to begin his reevaluation of her. By the time she returns to him (in "Come to Judgement" #34), having played a key role in saving his life, literally handing him the skull of his enemy, they've already reached a new level of equilibrium. (Scans courtesy of so_spiffed.)

From his consort, to his lieutenant. And by "Morningstar" (#63-65), as they reunite when the stakes are higher still, she has become even more than that:

To bring it back to the essay that started off this training of thought, I suppose my point is that Mazikeen's death was "heroic" (in the Eastern sense), but had her story ended there - had she never been resurrected - we would never have learnt what she had given up to follow the one she loved and worshipped. We would never have known the Mazikeen that was so memorably strong and independent in later issues, the Mazikeen that Lucifer felt such affinity with. She would have forever remained "Lucifer's whore". Dying was not enough to make her a hero; she had to live.